40 start with L start with L

In presidential election years the leadership qualities of occupants of the Oval Office become yardsticks for aspiring candidates. What profile of qualities, both positive and negative, helps explain the performance of chief executives? In this book about the White House, nine eminent political scientists and historians present their assessments of the leadership styles and organizational talents of presidents from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan. Filled with anecdote and insight, this is an unprecedented opportunity to observe how the running of the office of President has been changed, subtly and not so subtly, by the management and personal styles of the various incumbents within their historical contexts.

The book vividly depicts each president. There is Roosevelt, “a real artist in government”; Truman, a strong executive who always managed to appear weak; Eisenhower, who cultivated the image of being “above the fray” of politics but was actually fully occupied with getting political results; Kennedy, who successfully projected the symbolic grandeur of his office; Johnson, a figure from classical tragedy; Nixon, who preferred a corporate to a political mode of operation; Ford, who placed healing the nation’s wounds from Vietnam and Watergate above his personal political future; Carter, whose fall was as stunning as his rise was meteoric. The chapter on Reagan is an impassioned encomium of the president as a folk philosopher that is bound to be controversial.

These accounts of leadership by modern presidents are acute studies of how the presidency has become the first among equals in our tripartite system of government. This book will be important to political scientists, historians, and government officials, and the liveliness of its presentation and the quotidian impact of the men it describes will make it attractive to everyone interested in how we are governed and who is doing the governing.

Does the movement to a large number of early presidential primaries reduce the ability of voters to learn about the candidates? Do voters who vote early miss important information by not following the entire campaign, or are they, as some argue, more partisan? In a unique study Rebecca B. Morton and Kenneth C. Williams investigate the impact these changes have on the choices voters make. The authors combine a formal, theoretical model to derive hypotheses with experiments, elections conducted in labs, to test the hypotheses.

Their analysis finds that sequence in voting does matter. In simultaneous voting elections well-known candidates are more likely to win, even if that candidate is the first preference of only a minority of the voters and would be defeated by another candidate, if that candidate were better known. These results support the concerns of policy makers that front-loaded primaries prevent voters from learning during the primary process. The authors also find evidence that in sequential elections those who vote on election day have the benefit of information received throughout the whole course of the campaign, thus supporting concerns with mail-in ballots and other early balloting procedures.

This book will interest scholars interested in elections, the design of electoral systems, and voting behavior as well as the use of formal modeling and experiments in the study of politics. It is written in a manner that can be easily read by those in the public concerned with presidential elections and voting.

Rebecca B. Morton is Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Iowa. Kenneth C. Williams is Associate Professor of Political Science, Michigan State University.

Additional images, videos, and supplemental readings are available at the Gallaudet University Press/Manifold online platform.

A unique document in the history of the Kennedy years, these letters give us a firsthand look at the working relationship between a president and one of his close advisers, John Kenneth Galbraith. In an early letter, Galbraith mentions his "ambition to be the most reticent adviser in modern political history." But as a respected intellectual and author of the celebrated The Affluent Society, he was not to be positioned so lightly, and his letters are replete with valuable advice about economics, public policy, and the federal bureaucracy. As the United States' ambassador to India from 1961 to 1963, Galbraith made use of his position to counsel the President on foreign policy, especially as it bore on the Asian subcontinent and, ultimately, Vietnam.

Written with verve and wit, his letters were relished by a president who had little patience for foolish ideas or bad prose. They stand out today as a vibrant chronicle of some of the most subtle and critical moments in the days of the Kennedy administration--and a fascinating record of the counsel that Galbraith offered President Kennedy. Ranging from a pithy commentary on Kennedy's speech accepting the 1960 Democratic presidential nomination (and inaugurating the "New Frontier") to reflections on critical matters of state such as the Cuban Missile Crisis and the threat of Communism in Indochina, Letters to Kennedypresents a rare, intimate picture of the lives and minds of a political intellectual and an intellectual politician during a particularly bright moment in American history.

Most scholars and pundits today view Franklin Delano Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy as aggressive liberal leaders, while viewing Schlesinger’s famous histories of their presidencies as celebrations of their steadfast progressive leadership. A more careful reading of Schlesinger’s work demonstrates that he preferred an ironic political outlook emphasizing the virtues of restraint, patience, and discipline. For Schlesinger, Roosevelt and Kennedy were liberal heroes and models as much because they respected the constraints on their power and ideals as because they tested traditional institutions and redefined the boundaries of presidential power.

Aggressive liberalism involves the use of inspirational rhetoric and cunning political tactics to expand civil liberties and insure economic equality. Schlesinger’s emphasis on the crucial role that irony has played and should play in liberalism poses a challenge to the aggressive liberalism advocated by liberal activists, political thinkers, and pundits. That his counsel was grounded in conservative insights as well as liberal values makes it accessible to leaders across the political spectrum.

His memoir, interspersed with personal wisdom gleaned over more than six decades of service and leadership, encapsulates Sandy’s shrewd yet optimistic view of the public university as an institution. At every stage in his life—in the U.S. Navy during World War II, while practicing law or teaching, and in leadership positions at Chicago’s Field Museum and the University of Iowa— Sandy relied on his principles of open disclosure, inclusiveness, and respect for differences to guide him on issues that matter.

This chronicle of Sandy’s experiences throughout his life shows us the evolution both of the University of Iowa and of the nation writ large. More importantly, this book gives us a lens through which to examine our present situation, whether debating free speech on campus, the role of the arts and humanities in civil society, or the importance of funding for educational and cultural institutions.

Joseph F. Smith was born in 1838 to Hyrum Smith and Mary Fielding Smith. Six years later both his father and his uncle, Joseph Smith Jr., the founding prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, were murdered in Carthage, Illinois. The trauma of that event remained with Joseph F. for the rest of his life, affecting his personal behavior and public tenure in the highest tiers of the LDS Church, including the post of president from 1901 until his death in 1918. Joseph F. Smith laid the theological groundwork for modern Mormonism, especially the emphasis on temple work. This contribution was capped off by his “revelation on the redemption of the dead,” a prophetic glimpse into the afterlife. Taysom’s book traces the roots of this vision, which reach far more deeply into Joseph F. Smith’s life than other scholars have previously identified.

In this first cradle-to-grave biography of Joseph F. Smith, Stephen C. Taysom uses previously unavailable primary source materials to craft a deeply detailed, insightful story of a prominent member of a governing and influential Mormon family. Importantly, Taysom situates Smith within the historical currents of American westward expansion, rapid industrialization, settler colonialism, regional and national politics, changing ideas about family and masculinity, and more. Though some writers tend to view the LDS Church and its leaders through a lens of political and religious separatism, Taysom does the opposite, pushing Joseph F. Smith and the LDS Church closer to the centers of power in Washington, DC, and elsewhere.

Born on the same day in 1809, Abraham Lincoln and Charles Darwin were true contemporaries. Though shaped by vastly different environments, they had remarkably similar values, purposes, and approaches. In this exciting new study, James Lander places these two iconic men side by side and reveals the parallel views they shared of man and God.

While Lincoln is renowned for his oratorical prowess and for the Emancipation Proclamation, as well as many other accomplishments, his scientific and technological interests are not widely recognized; for example, many Americans do not know that Lincoln is the only U.S. president to obtain a patent. Darwin, on the other hand, is celebrated for his scientific achievements but not for his passionate commitment to the abolition of slavery, which in part drove his research in evolution. Both men took great pains to avoid causing unnecessary offense despite having abandoned traditional Christianity. Each had one main adversary who endorsed scientific racism: Lincoln had Stephen A. Douglas, and Darwin had Louis Agassiz.

With graceful and sophisticated writing, Lander expands on these commonalities and uncovers more shared connections to people, politics, and events. He traces how these two intellectual giants came to hold remarkably similar perspectives on the evils of racism, the value of science, and the uncertainties of conventional religion.

Separated by an ocean but joined in their ideas, Lincoln and Darwin acted as trailblazers, leading their societies toward greater freedom of thought and a greater acceptance of human equality. This fascinating biographical examination brings the mid-nineteenth-century discourse about race, science, and humanitarian sensibility to the forefront using the mutual interests and pursuits of these two historic figures.

Abraham Lincoln’s faith has commanded more broad-based attention than that of any other American president. Although he never joined a denomination, Baptists, Presbyterians, Quakers, Episcopalians, Disciples of Christ, Spiritualists, Jews, and even atheists claim the sixteenth president as one of their own. In this concise volume, Ferenc Morton Szasz and Margaret Connell Szasz offer both an accessible survey of the development of Lincoln’s religious views and an informative launch pad for further academic inquiry. A singular key to Lincoln’s personality, especially during the presidential years, rests with his evolving faith perspective.

After surveying Lincoln’s early childhood as a Hard-Shell Baptist in Kentucky and Indiana, the authors chronicle his move from skepticism to participation in Episcopal circles during his years in Springfield, and, finally, after the death of son Eddie, to Presbyterianism. They explore Lincoln’s relationship with the nation’s faiths as president, the impact of his son Willie’s death, his adaptation of Puritan covenant theory to a nation at war, the role of prayer during his presidency, and changes in his faith as reflected in the Emancipation Proclamation and his state papers and addresses. Finally, they evaluate Lincoln’s legacy as the central figure of America’s civil religion, an image sharpened by his prominent position in American currency.

A closing essay by Richard W. Etulain traces the historiographical currents in the literature on Lincoln and religion, and the volume concludes with a compilation of Lincoln’s own words about religion.

In assessing the enigma of Lincoln’s Christianity, the authors argue that despite his lack of church membership, Lincoln lived his life through a Christian ethical framework. His years as president, dominated by the Civil War and personal loss, led Lincoln to move into a world beholden to Providence.

When war erupted in 1861, the North—despite its superior economic resources and manpower—was considered the underdog of the conflict. The need to invade the South brought no advantage to the inefficient, poorly led Union Army. In contrast, Southerners’ knowledge of their home terrain, access to railroads, familiarity with firearms, and outdoor lifestyles, along with the presumed support of foreign nations, made victory over the North seem a likely outcome. In the face of such daunting obstacles, only one person could unite disparate Northerners and rally them to victory in the darkest moments of the war: Abraham Lincoln.

While Lincoln is often remembered today as one of America’s wisest presidents, he was not always considered so sage. Burlingame demonstrates how, long before the rigors of his presidency and the Civil War began to affect him, Lincoln wrestled with the demons of midlife to ultimately emerge as arguably the most self-aware, humble, and confident leader in American history. This metamorphosis from sarcastic young politician to profound statesman uniquely prepared him for the selfless dedication the war years would demand. Whereas his counterpart, Jefferson Davis, became mired in personal power plays, perceived slights, and dramas, Lincoln rose above personal concerns to always place the preservation of the Union first. Lincoln’s ability, along with his eloquence, political savvy, and grasp of military strategy made him a formidable leader whose honesty and wisdom inspired undying loyalty.

In addition to offering fresh perspectives on Lincoln’s complex personality and on the other luminaries of his administration, Lincoln and the Civil War takes readers on a brief but thorough tour of the war itself, from the motivations and events leading to Southern secession and the first shots at Fort Sumter to plans for Reconstruction and Lincoln’s tragic assassination. Throughout the journey, Burlingame demonstrates how Lincoln’s steady hand at the helm navigated the Union through the most perilous events of the war and held together the pieces of an unraveling nation.

Although Lincoln rose to national prominence in 1858 during his debates with Stephen Douglas, he was unable to publicly stump for the presidency in a time when personal campaigning for the office was traditionally rejected. This limitation did nothing to check Lincoln’s ambitions, however, as he consistently endeavored to place himself in the public eye while stealthily pulling political strings behind the scenes. Green demonstrates how Lincoln drew upon his considerable communication abilities and political acumen to adroitly manage allies and enemies alike, ultimately uniting the Republican Party and catapulting himself from his status as one of the most unlikely of candidates to his party’s nominee at the national convention.

As the general election campaign progressed, Lincoln continued to draw upon his experience from three decades in Illinois politics to unite and invigorate the Republican Party. Democrats fell to divisions between North and South, setting the stage for a Republican victory in November—and for the most turbulent times in U.S. history.

Moving well beyond a study of the man to provide astute insight into the era’s fiery political scene and its key players, Green offers perceptive analysis of the evolution of American politics and Lincoln’s political career, the processes of the national and state conventions, how political parties selected their candidates, national developments of the time and their effects on Lincoln and his candidacy, and Lincoln’s own sharp—and often surprising—assessments of his opponents and colleagues. Green frequently employs Lincoln’s own words to afford an intimate view into the political savvy of the future president.

The pivotal election of 1860 previewed the intelligence, patience, and shrewdness that would enable Lincoln to lead the United States through its greatest upheaval. This exciting new book brings to vivid life the cunning and strength of one of America’s most intriguing presidents during his journey to the White House.

Lincoln as Hero shows how—whether it was as president, lawyer, or schoolboy—Lincoln extolled the foundational virtues of American society. Williams describes the character and leadership traits that define American heroism, including ideas and beliefs, willpower, pertinacity, the ability to communicate, and magnanimity. Using both celebrated episodes and lesser-known anecdotes from Lincoln’s life and achievements, Williams presents a wide-ranging analysis of these traits as they were demonstrated in Lincoln’s rise, starting with his self-education as a young man and moving on to his training and experience as a lawyer, his entry onto the political stage, and his burgeoning grasp of military tactics and leadership.

Williams also examines in detail how Lincoln embodied heroism in standing against secession and fighting to preserve America’s great democratic experiment. With a focused sense of justice and a great respect for the mandates of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, Lincoln came to embrace freedom for the enslaved, and his Emancipation Proclamation led the way for the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery. Lincoln’s legacy as a hero and secular saint was secured when his lifeended by assassination as the Civil War was drawing to a close

Touching on Lincoln’s humor and his quest for independence, justice, and equality, Williams outlines the path Lincoln took to becoming a great leader and an American hero, showing readers why his heroism is still relevant. True heroes, Williams argues, are successful not just by the standards of their own time but also through achievements that transcend their own eras and resonate throughout history—with their words and actions living on in our minds, if we are imaginative, and in our actions, if we are wise.

Univeristy Press Books for Public and Secondary Schools 2013 edition

More than any other American before or since, Abraham Lincoln had a way with words that has shaped our national idea of ourselves. Actively disliked and even vilified by many Americans for the vast majority of his career, this most studied, most storied, and most documented leader still stirs up controversy. Showing not only the development of a powerful mind but the ways in which our sixteenth president was perceived by equally brilliant American minds of a decidedly literary and political bent, Harold K. Bush’s Lincoln in His Own Time provides some of the most significant contemporary meditations on the Great Emancipator’s legacy and cultural significance.

The forty-two entries in this spirited collection present the best reflections of Lincoln as thinker, reader, writer, and orator by those whose lives intertwined with his or those who had direct contact with eyewitnesses. Bush focuses on Lincoln’s literary interests, reading, and work as a writer as well as the evolving debate about his religious views that became central to his memory. Along with a star-struck Walt Whitman writing of Lincoln’s “inexpressibly sweet” face and manner, Elizabeth Keckly’s description of a bereaved Lincoln, “genius and greatness weeping over love’s idol lost,” and William Stoddard’s report of the “cheery, hopeful, morning light” on Lincoln’s face after a long night debating the fate of the nation, the volume includes selections from works by famous contemporary figures such as Hawthorne, Douglass, Stowe, Lowell, Twain, and Lincoln himself in addition to lesser-known selections that have been nearly lost to history. Each entry is introduced by a headnote that places the selection in historical and cultural context; explanatory endnotes provide information about people and places. A comprehensive introduction and a detailed chronology of Lincoln’s eventful life round out the volume.

Bush’s thoughtful collection reveals Lincoln as a man of letters who crafted some of the most memorable lines in our national vocabulary, explores the striking mythologization of the martyred president that began immediately upon his death, and then combines these two themes to illuminate Lincoln’s place in public memory as the absolute embodiment of America’s mythic civil religion. Beyond providing the standard fare of reminiscences about the rhetorically brilliant backwoodsman from the “Old Northwest,” Lincoln in His Own Time also maps a complex genealogy of the cultural work and iconic status of Lincoln as quintessential scribe and prophet of the American people.

Lincoln in Indiana tells the story of Lincoln’s life in Indiana, from his family’s arrival to their departure. Dirck explains the Lincoln family’s ancestry and how they and their relatives came to settle near Pigeon Creek. He shows how frontier families like the Lincolns created complex farms out of wooded areas, fashioned rough livelihoods, and developed tight-knit communities in the unforgiving Indiana wilderness. With evocative prose, he describes the youthful Lincoln’s relationship with members of his immediate and extended family. Dirck illuminates Thomas Lincoln by setting him into his era, revealing the concept of frontier manhood, and showing the increasingly strained relationship between father and son. He illustrates how pioneer women faced difficulties as he explores Nancy Lincoln’s work and her death from milk sickness; how Lincoln’s stepmother, Sarah Bush, fit into the family; and how Lincoln’s sister died in childbirth. Dirck examines Abraham’s education and reading habits, showing how a farming community could see him as lazy for preferring book learning over farmwork. While explaining how he was both similar to and different from his peers, Dirck includes stories of Lincoln’s occasional rash behavior toward those who offended him. As Lincoln grew up, his ambitions led him away from the family farm, and Dirck tells how Lincoln chafed at his father’s restrictions, why the Lincolns decided to leave Indiana in 1830, and how Lincoln eventually broke away from his family.

In a triumph of research, Dirck cuts through the myths about Lincoln’s early life, and along the way he explores the social, cultural, and economic issues of early nineteenth-century Indiana. The result is a realistic portrait of the youthful Lincoln set against the backdrop of American frontier culture.

In Lincoln Lessons, seventeen of today’s most respected academics, historians, lawyers, and politicians provide candid reflections on the importance of Abraham Lincoln in their intellectual lives. Their essays, gathered by editors Frank J. Williams and William D. Pederson, shed new light on this political icon’s remarkable ability to lead and inspire two hundred years after his birth.

Collected here are glimpses into Lincoln’s unique ability to transform enemies into steadfast allies, his deeply ingrained sense of morality and intuitive understanding of humanity, his civil deification as the first assassinated American president, and his controversial suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War. The contributors also discuss Lincoln’s influence on today’s emerging democracies, his lasting impact on African American history, and his often-overlooked international legend—his power to instigate change beyond the boundaries of his native nation. While some contributors provide a scholarly look at Lincoln and some take a more personal approach, all explore his formative influence in their lives. What emerges is the true history of his legacy in the form of first-person testaments from those whom he has touched deeply.

Lincoln Lessons brings together some of the best voices of our time in a unique combination of memoir and history. This singular volume of original essays is a tribute to the enduring inspirational powers of an extraordinary man whose courage and leadership continue to change lives today.

Contributors

Jean H. Baker

Mario M. Cuomo

Joan L. Flinspach

Sara Vaughn Gabbard

Doris Kearns Goodwin

Harold Holzer

Harry V. Jaffa

John F. Marszalek

James M. McPherson

Edna Greene Medford

Sandra Day O’Connor

Mackubin Thomas Owens

William D. Pederson

Edward Steers Jr.

Craig L. Symonds

Thomas Reed Turner

Frank J. Williams

In Lincoln the Inventor, Jason Emerson offers the first treatment of Abraham Lincoln’s invention of a device to buoy vessels over shoals and its subsequent patent as more than mere historical footnote.

In this book, Emerson shows how, when, where, and why Lincoln created his invention; how his penchant for inventions and inventiveness was part of his larger political belief in internal improvements and free labor principles; how his interest in the topic led him to try his hand at scholarly lecturing; and how Lincoln, as president, encouraged and even contributed to the creation of new weapons for the Union during the Civil War.

During his extensive research, Emerson also uncovered previously unknown correspondence between Lincoln’s son, Robert, and his presidential secretary, John Nicolay, which revealed the existence of a previously unknown draft of Abraham Lincoln’s lecture “Discoveries and Inventions.” Emerson not only examines the creation, delivery, and legacy of this lecture, but also reveals for the first time how Robert Lincoln owned this unknown version, how he lost and later tried to find it, the indifference with which Robert and Nicolay both held the lecture, and their decision to give it as little attention as possible when publishing President Lincoln’s collected works.

The story of Lincoln’s invention extends beyond a boat journey, the whittling of some wood, and a trip to the Patent Office; the invention had ramifications for Lincoln’s life from the day his flatboat got stuck in 1831 until the day he died in 1865. Besides giving a complete examination of this important—and little known—aspect of Lincoln’s life, Lincoln the Inventor delves into the ramifications of Lincoln’s intellectual curiosity and inventiveness, both as a civilian and as president, and considers how it allows a fresh insight into his overall character and contributed in no small way to his greatness. Lincoln the Inventor is a fresh contribution to the field of Lincoln studies about a topic long neglected. By understanding Lincoln the inventor, we better understand Lincoln the man.

The book that inspired the popular Concise Lincoln Library series

In April 1831, on a flatboat grounded on the Rutledge milldam below the town of New Salem, Abraham Lincoln worked to pry the boat loose, directed the crew, and ran into the village to borrow an auger to bore a hole in the end hanging over the dam, causing the water to drain and the boat to float free. Seventeen years later, while traveling home from a round of political speeches, Lincoln witnessed another similar occurrence. For the rest of his journey, he considered how to construct a device to free stranded boats from shallow waters.

In this first thorough examination of Abraham Lincoln’s mechanical mind, Jason Emerson brings forth the complete story of Lincoln’s invention and patent as more than mere historical footnote. Emerson shows how, when, where, and why Lincoln developed his invention; how his penchant for inventions and innovation was part of his larger political belief in internal improvements and free labor principles; how his interest in the topic led him to try his hand at scholarly lecturing; and how Lincoln, as president, encouraged and even contributed to the creation of new weapons for the Union during the Civil War.

Lincoln the Inventor delves into the ramifications of Lincoln’s intellectual curiosity and inventiveness, both as a civilian and as president, and considers how they allow a fresh insight into his overall character and contributed in no small way to his greatness. By understanding Lincoln the inventor, we better understand Lincoln the man.

The volume’s contributors not only address specific situations and issues that assisted in Lincoln’s development of a new understanding of law and its application but also show Lincoln’s remarkable presidential leadership. Among the topics covered are civil liberties during wartime; presidential pardons; the law and Lincoln’s decision-making process; Lincoln’s political ideology and its influence on his approach to citizenship; Lincoln’s defense of the Constitution, the Union, and popular government; constitutional restraints on Lincoln as he dealt with slavery and emancipation; the Lieber codes, which set forth how the military should deal with civilians and with prisoners of war; the loyalty (or treason) of government employees, including Lincoln’s domestic staff; and how Lincoln’s image has been used in presidential rhetoric. Although varied in their strategies and methodologies, these essays expand the understanding of Lincoln’s vision for a united nation grounded in the Constitution.

Lincoln, the Law, and Presidential Leadership shows how the sixteenth president’s handling of complicated legal issues during the Civil War, which often put him at odds with the Supreme Court and Congress, brought the nation through the war intact and led to a transformation of the executive branch and American society.

Despite historians' focus on the man as president and politician, Abraham Lincoln lived most of his adult life as a practicing lawyer. It was as a lawyer that he fed his family, made his reputation, bonded with Illinois, and began his political career. Lawyering was also how Lincoln learned to become an expert mediator between angry antagonists, as he applied his knowledge of the law and of human nature to settle one dispute after another. Frontier lawyers worked hard to establish respect for the law and encourage people to resolve their differences without intimidation or violence. These were the very skills Lincoln used so deftly to hold a crumbling nation together during his presidency.

The growth of Lincoln's practice attests to the trust he was able to inspire, and his travels from court to court taught him much about the people and land of Illinois. Lincoln the Lawyer explores the origins of Lincoln's desire to practice law, his legal education, his partnerships with John Stuart, Stephen Logan, and William Herndon, and the maturation of his far-flung practice in the 1840s and 1850s. Brian Dirck provides a context for law as it was practiced in mid-century Illinois and evaluates Lincoln's merits as an attorney by comparison with his peers. He examines Lincoln's clientele, his circuit practice, his views on legal ethics, and the supposition that he never defended a client he knew to be guilty. This approach allows readers not only to consider Lincoln as he lived his life--it also shows them how the law was used and developed in Lincoln's lifetime, how Lincoln charged his clients, how he was paid, and how he addressed judge and jury.

To fully understand and appreciate Abraham Lincoln’s legacy, it is important to examine the society that influenced the life, character, and leadership of the man who would become the Great Emancipator. Editors Joseph R. Fornieri and Sara Vaughn Gabbard have done just that in Lincoln’s America: 1809–1865, a collection of original essays by ten eminent historians that place Lincoln within his nineteenth-century cultural context.

Among the topics explored in Lincoln’s America are religion, education, middle-class family life, the antislavery movement, politics, and law. Of particular interest are the transition of American intellectual and philosophical thought from the Enlightenment to Romanticism and the influence of this evolution on Lincoln's own ideas.

By examining aspects of Lincoln’s life—his personal piety in comparison with the beliefs of his contemporaries, his success in self-schooling when frontier youths had limited opportunities for a formal education, his marriage and home life in Springfield, and his legal career—in light of broader cultural contexts such as the development of democracy, the growth of visual arts, the question of slaves as property, and French visitor Alexis de Tocqueville’s observations on America, the contributors delve into the mythical Lincoln of folklore and discover a developing political mind and a changing nation.

As Lincoln’s America shows, the sociopolitical culture of nineteenth-century America was instrumental in shaping Lincoln’s character and leadership. The essays in this volume paint a vivid picture of a young nation and its sixteenth president, arguably its greatest leader.

During the 1860 and 1864 presidential campaigns, Abraham Lincoln was the subject of over twenty campaign biographies. In this innovative study, Thomas A. Horrocks examines the role that these publications played in shaping an image of Lincoln that would resonate with voters and explores the vision of Lincoln that the biographies crafted, the changes in this vision over the course of four years, and the impact of these works on the outcome of the elections.

Horrocks investigates Lincoln’s campaign biographies within the context of the critical relationship between print and politics in nineteenth-century America and compares the works about Lincoln with other presidential campaign biographies of the era. Horrocks shows that more than most politicians of his day, Lincoln deeply appreciated and understood the influence and the power of the printed word.

The 1860 campaign biographies introduced to America “Honest Abe, the Rail Splitter,” a trustworthy, rugged candidate who appealed to rural Americans. When Lincoln ran for reelection in 1864, the second round of campaign biographies complemented this earlier portrait of Lincoln with a new, paternal figure, “Father Abraham,” more appropriate for Americans enduring a bloody civil war. Closing with a consideration of the influence of these publications on Lincoln’s election and reelection, Lincoln’s Campaign Biographies provides a new perspective for those seeking a better understanding of the sixteenth president and two of the most critical elections in American history.

After listening to Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address, many in the audience were stunned. Instead of a positive message about the coming Union victory, the president implicated the entire country in the faults and responsibility for slavery. Using Old Testament references, Lincoln explained that God was punishing all Americans for their role in the calamity with a bloody civil war.

These were surprising words from a man who belonged to no church, did not regularly attend services, and was known to have publicly and privately questioned some of Christianity’s core beliefs. But Lincoln’s life was one with supreme sadness—the death of his first fiancee, the subsequent loss of two of his sons—and these events, along with the chance encounter with a book in Mary Todd’s father’s library, The Christian’s Defense, are all part of the key to understanding Lincoln’s Christianity. Biblical quotations soon entered his speeches—a point noted by Stephen Douglas in their debates—but it is unclear whether Lincoln’s use of scripture was a signal that American politicians should openly embrace religion in their public lives, or a rhetorical tool to manipulate his audience, or a result of a personal religious transformation. After his death both secular and religious biographers claimed Lincoln as one of their own, touching off a controversy that remains today.

In Lincoln’s Christianity, Michael Burkhimer examines the entire history of the president’s interaction with religion—accounts from those who knew him, his own letters and writings, the books he read—to reveal a man who did not believe in orthodox Christian precepts (and might have had a hard time getting elected today) yet, by his example, was a person and president who most truly embodied Christian teachings.

How a traditionalist became part of Lincoln's volatile team of rivals

Edward Bates, a founding father of Missouri and leader of the Missouri Whig Party, served as Abraham Lincoln’s attorney general during the American Civil War. The first full biography of Bates in nearly sixty years, Lincoln’s Conservative Advisor reveals a striking portrait of this complex figure in Lincoln’s cabinet.

Author Mark A. Neels begins with Bates’s youth in Virginia and follows him through his political and judicial career, his candidacy as a Republican presidential nominee in 1860, and his appointment to Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet as attorney general. Bates became an essential advisor to the president on key legal, military, and political matters from emancipation to civil liberties and equal rights, and his official opinion on Habeas Corpus would have a permanent effect on presidential authority and separation of powers. When Lincoln drafted the Emancipation Proclamation, Bates found himself at odds with the president and the radical anti-slavery members of the cabinet. But more than simply highlighting the conflict within Lincoln’s administration, Bates’s example lays bare the strong philosophical divisions within the Republican Party during the Civil War era. These divisions were present at the party’s inception, crystallized during the war, and ultimately sparked a political realignment during Reconstruction. Bates was at the center of this divide for most of its existence, and in some cases assisted in its promulgation.

Bates, a fierce opponent of radical Republicanism, embodies the conflict among Republicans over issues of slavery and citizenship. In both judicial and elective office, he was compelled by a sense of duty to defy the populism of President Andrew Jackson and Senator Thomas Hart Benton, and, later, the proslavery forces that threatened to tear the nation apart. Though he had owned slaves, Bates represented at least one enslaved woman’s suit for freedom, released from bondage the people he had enslaved, and aided Lincoln in his efforts to end slavery nationwide. Bates’s opinion on citizenship as attorney general helped pave the way for equal rights. His opinions were not always popular with either his colleagues or the greater populace, but Bates remained true to his conservative principles—a set of values shared by a large swath of Lincoln’s Republican Party—which positioned him as a leading opponent of radical Republicanism during the Reconstruction Era.

A skilled historian and a masterful storyteller himself, Thomas was widely regarded as the greatest Lincoln historian of his generation. With these essays, he combines historical depth with narrative grace in delineating Lincoln's qualities as a humorist, lawyer, and politician. From colorful tall tales to clever barbs aimed at political opponents, Lincoln clothed a shrewd wit in a homespun, backwoods vernacular. He used humor to defuse tension, illuminate a point, put others at ease--and sometimes for sheer fun. From an early reliance on broad humor and ridicule in speeches and on the stump, Lincoln's style shifted in 1854 to a more serious vein in which humor came primarily to elucidate an argument. "If I did not laugh occasionally I should die," he is said to have told his cabinet, "and you need this medicine as much as I do." Thomas brings his deep knowledge of Lincoln to essays on the great man's tumultuous career in Congress, his work as a lawyer, his experiences in the Courts, and his opinions of the South. A gracious survey of Lincoln's early biographers, particularly Ida Tarbell, stands alongside an appreciation of Harry Edward Pratt, a key figure in the early days of the Abraham Lincoln Association. Thomas also assesses Lincoln's use of language and the ongoing significance of the Gettysburg Address.

This diverse collection is enhanced by an introduction by Michael Burlingame, himself a leading biographer of Lincoln. Burlingame provides a balanced portrait of Thomas and his circuitous path toward writing history.

Lincoln Prize winner William C. Harris turns to the last months of Abraham Lincoln's life in an attempt to penetrate this central figure of the Civil War, and arguably America's greatest president. Beginning with the presidential campaign of 1864 and ending with his shocking assassination, Lincoln's ability to master the daunting affairs of state during the final nine months of his life proved critical to his apotheosis as savior and saint of the nation.

In the fall of 1864, an exhausted president pursued the seemingly intractable end of the Civil War. After four years at the helm, Lincoln was struggling to save his presidency in an election that he almost lost because of military stalemate and his commitment to restore the Union without slavery. Lincoln's victory in the election not only ensured the success of his agenda but led to his transformation from a cautious, often hesitant president into a distinguished statesman. He moved quickly to defuse destructive partisan divisions and to secure the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment. And he skillfully advanced peace terms that did not involve the unconditional surrender of Confederate armies. Throughout this period of great trials, he managed to resist political pressure from Democrats and radical Republicans and from those seeking patronage and profit. By expanding the context of Lincoln's last months beyond the battlefield, Harris shows how the events of 1864-65 tested the president's life and leadership and how he ultimately emerged victorious, and became Father Abraham to a nation.

The four new essays in Lincoln's Legacy describe major ethical problems that the sixteenth president navigated what can be learned from how he did so. The distinguished and award-winning Lincoln scholars William Miller, Mark E. Neely Jr., Phillip Shaw Paludan, and Mark Summers describe Lincoln’s attitudes and actions during encounters with questions of politics, law, constitutionalism, patronage, and democracy. The remarkably focused essays include an assessment of Lincoln's virtues in the presidency, the first study on Lincoln and patronage in more than a decade, a challenge to the cliché of Lincoln the democrat, and a study of habeas corpus, Lincoln, and state courts. On the eve of the bicentennial celebration of Lincoln’s birth, Lincoln’s Legacy highlights his enduring importance in contemporary conversations about law, politics, and democracy.

"Abraham Lincoln was a member of the Illinois Legislature from

1834 to 1842 -- one of the Long Nine, as the Sangamon County delegation

was known, all its members being more than six feet tall. It was during

these eight years that he came as close to scandal as he was ever to come

in his public or private life. Did he, or did he not, engage in shameless

logrolling to get the state capital moved to Springfield? This and other

aspects of Lincoln's apprenticeship in the legislator . . . are thoroughly

investigated."

-- Chicago Sun-Times

"The wealth of detail it contains makes it a worthwhile addition

to the study of Lincoln's legislative career."

-- Los Angeles Times

Insightful and revealing, Lincoln’s Rise to Eloquence follows Lincoln from his early career through the years-long clashes with Stephen A. Douglas to trace the future president’s evolution as a communicator and politician.

Greene begins with the story of how Truman and Vaughan met during World War I, then examines Vaughan’s support for Truman for the Senate and later as President. The majority of the book, however, considers the various cronies that surrounded Vaughan and illustrates the significance of his relationship with Truman—and the president’s inability to rein him in.

Drawing from primary and archival sources, many never before published, Little Helpers is further distinguished by its use of the correspondence between Vaughan and Truman. Greene also provides a dramatic narrative account of the inner workings of the Truman administration, making the book accessible to the general reader as well as the specialist.

In an opening section focusing largely on Lincoln's formative years, insightful explorations into his early self-education and the era before his presidency come from editors Frank J. Williams and Harold Holzer, respectively. Readers will also glimpse a Lincoln rarely discerned in books: calculating politician, revealed in Matthew Pinsker's illuminating essay, and shrewd military strategist, as demonstrated by Craig L. Symonds. Stimulating discussions from Edna Greene Medford, John Stauffer, and Michael Vorenberg tell of Lincoln's friendship with Frederick Douglass, his gradualism on abolition, and his evolving thoughts on race and the Constitution to round out part two. Part three features reflections on his martyrdom and memory, including a counterfactual history from Gerald J. Prokopowicz that imagines a hypothetical second term for the president, emphasizing the differences between Lincoln and his successor, Andrew Johnson. Barry Schwartz's contribution presents original research that yields fresh insight into Lincoln's evolving legacy in the South, while Richard Wightman Fox dissects Lincoln's 1865 visit to Richmond, and Orville Vernon Burton surveys and analyzes recent Lincoln scholarship.

This thought-provoking new anthology, introduced at a major bicentennial symposium at Harvard University, offers a wide range of ideas and interpretations by some of the best-known and most widely respected historians of our time. The Living Lincoln is essential reading for those seeking a better understanding of this nation's greatest president and how his actions resonate today.

A constitutional originalist sounds the alarm over the presidency’s ever-expanding powers, ascribing them unexpectedly to the liberal embrace of a living Constitution.

Liberal scholars and politicians routinely denounce the imperial presidency—a self-aggrandizing executive that has progressively sidelined Congress. Yet the same people invariably extol the virtues of a living Constitution, whose meaning adapts with the times. Saikrishna Bangalore Prakash argues that these stances are fundamentally incompatible. A constitution prone to informal amendment systematically favors the executive and ensures that there are no enduring constraints on executive power. In this careful study, Prakash contends that an originalist interpretation of the Constitution can rein in the “living presidency” legitimated by the living Constitution.

No one who reads the Constitution would conclude that presidents may declare war, legislate by fiat, and make treaties without the Senate. Yet presidents do all these things. They get away with it, Prakash argues, because Congress, the courts, and the public routinely excuse these violations. With the passage of time, these transgressions are treated as informal constitutional amendments. The result is an executive increasingly liberated from the Constitution. The solution is originalism. Though often associated with conservative goals, originalism in Prakash’s argument should appeal to Republicans and Democrats alike, as almost all Americans decry the presidency’s stunning expansion. The Living Presidency proposes a baker’s dozen of reforms, all of which could be enacted if only Congress asserted its lawful authority.

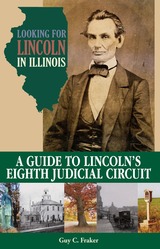

For twenty-three years Abraham Lincoln practiced law on the Eighth Judicial Circuit in east central Illinois, and his legal career is explored in Looking for Lincoln in Illinois: A Guide to Lincoln’s Eighth Judicial Circuit. Guy C. Fraker directs readers and travelers through the prairies to the towns Lincoln visited regularly. Twice a year, spring and fall, Lincoln’s work took him on a journey covering more than four hundred miles. As his stature as a lawyer grew, east central Illinois grew in population and influence, and the Circuit provided Lincoln with clients, friends, and associates who became part of the network that ultimately elevated him to the presidency.

This guidebook to the Circuit features Illinois courthouses, Looking for Lincoln Wayside Exhibits, and other Lincoln points of interest. Fraker guides travelers down the long stretches of quiet country roads that gave Lincoln time to read and think to the locations where Lincoln’s broad range of cases expanded his sense of the economic and social forces changing America.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2024

The University of Chicago Press