201 start with T start with T

Torpey’s argument advances the idea that there are in fact three “Axial Ages,” instead of one original Axial Age and several subsequent, smaller developments. Each of the three ages contributed decisively to how humanity lives, and the difficulties it faces. The earliest, or original, Axial Age was a moral one; the second was material, and revolved around the creation and use of physical objects; and the third is chiefly mental, and focused on the technological. While there are profound risks and challenges, Torpey shows how a worldview that combines the strengths of all three ages has the potential to usher in a period of exceptional human freedom and possibility.

The Three Ethologies offers a fresh, affirmative vision for rebuilding human-animal relations. Venturing beyond the usual scholarly and activist emphasis on restricting harm, Matthew Calarco develops a new philosophy for understanding animal behavior—a practice known as ethology—through three distinct but interrelated lenses: mental ethology, which rebuilds individual subjectivity; social ethology, which rethinks our communal relations; and environmental ethology, which reconfigures our relationship to the land we co-inhabit with our animal kin. Drawing on developments in philosophy, (eco)feminist theory, critical geography, Indigenous studies, and the environmental humanities, Calarco casts an inspiring vision of how ethological living can help us to reimagine our ideas about goodness, truth, and beauty.

The authors begin by inviting readers to step away from the Earth and reconsider our Sun. What we can directly observe of this star is limited to its surface, but with the advent of telescopes and spectroscopy, scientists know more than ever about its physical characteristics, origins, and projected lifetime. From the Sun, the authors journey further out into space to explore black holes. The Garfinkle brothers explain that our understanding of these astronomical oddities began in theory, and growing mathematical and physical evidence has unexpectedly supported it. From black holes, the authors lead us further into the unknown, to the dark matter and energy that pervade our universe, where science teeters on the edge of theory and discovery. Returning from the depths of space, the final section of the book brings the reader back down to Earth for a final look at the practice of science, ending with a practical guide to discerning real science from pseudoscience among the cacophony of print and online scientific sources.

Three Steps to the Universe will reward anyone interested in learning more about the universe around us and shows how scientists uncover its mysteries.

Thrifty Science explores this distinctive culture of experiment and demonstrates how the values of the household helped to shape an array of experimental inquiries, ranging from esoteric investigations of glowworms and sour beer to famous experiments such as Benjamin Franklin’s use of a kite to show lightning was electrical and Isaac Newton’s investigations of color using prisms. Tracing the diverse ways that men and women put their material possessions into the service of experiment, Werrett offers a history of practices of recycling and repurposing that are often assumed to be more recent in origin. This thriving domestic culture of inquiry was eclipsed by new forms of experimental culture in the nineteenth century, however, culminating in the resource-hungry science of the twentieth. Could thrifty science be making a comeback today, as scientists grapple with the need to make their research more environmentally sustainable?

A streak of light crosses the night sky as a bit of extraterrestrial material falls to Earth.

Meteorites, which range from particles of dust to massive chunks of metal and rock, bombard the Earth constantly, adding hundreds of tons of new material to our planet each day. What are these objects? How do we recover and study them? Where do they come from, and what do they tell us about the birth and infancy of the solar system? Why do many scientists now believe that meteorites have played a dramatic, albeit occasional, role in the evolution of life on Earth?

In Thunderstones and Shooting Stars, Robert T. Dodd gives us an up-to-date report on these questions. He summarizes the evidence that leads scientists to believe that most meteorites come from asteroids, although a few come from the moon and a few more from a planet, probably Mars. He explains how chondrites--the most numerous and primitive of meteorites--contribute to our evolving picture of the early solar system, and how some of them may tell us of events that took place beyond the sun and before its birth. Finally, he examines the controversial hypothesis that impacts by asteroids or comets have interrupted the evolution of life on Earth, accounting for such geological puzzles as the rapid demise of the dinosaurs.

Meteorites have been called "the poor man's space probe," for they are the only extraterrestrial rocks that we can collect without benefit of spacecraft. This lively and accessible book both illuminates the complex science of meteoritics and conveys a sense of its excitement. University teachers and students will appreciate its synthesis of new research on a broad range of topics, and amateurs will delight in its lucid presentation of a science that is unlocking many mysteries of Earth and space.

Tibetan Buddhism and Modern Physics: Toward a Union of Love and Knowledge addresses the complex issues of dialogue and collaboration between Buddhism and science, revealing connections and differences between the two. While assuming no technical background in Buddhism or physics, this book strongly responds to the Dalai Lama’s “heartfelt plea” for genuine collaboration between science and Buddhism. The Dalai Lama has written a foreword to the book and the Office of His Holiness will translate it into both Chinese and Tibetan.

Tidal Marsh Restoration provides the scientific foundation and practical guidance necessary for coastal zone stewards to initiate salt marsh tidal restoration programs. The book compiles, synthesizes, and interprets the current state of knowledge on the science and practice of salt marsh restoration, bringing together leaders across a range of disciplines in the sciences (hydrology, soils, vegetation, zoology), engineering (hydraulics, modeling), and public policy, with coastal managers who offer an abundance of practical insight and guidance on the development of programs.

The work presents in-depth information from New England and Atlantic Canada, where the practice of restoring tidal flow to salt marshes has been ongoing for decades, and shows how that experience can inform restoration efforts around the world. Students and researchers involved in restoration science will find the technical syntheses, presentation of new concepts, and identification of research needs to be especially useful as they formulate research and monitoring questions, and interpret research findings.

Tidal Marsh Restoration is an essential work for managers, planners, regulators, environmental and engineering consultants, and others engaged in planning, designing, and implementing projects or programs aimed at restoring tidal flow to tide-restricted or diked salt marshes.

Illustrated with maps, photographs, and diagrams, this volume provides a clear account of the factors that make these habitats unique and vulnerable. It discusses their formation, the conditions affecting their plant and animal life, and the diversity of types across North America, as well as their history, use by wildlife and humans, current status, conservation, restoration, and likely future. The emphasis is on vegetated wetlands—marshes and swamps—with additional discussion of eelgrass meadows, rocky shores, beaches, and tidal flats.

Ralph Tiner's previous field guides to coastal wetland plants in the Northeast and Southeast have been widely praised. Tidal Wetlands Primer joins Tiner's earlier publications as an authoritative and user-friendly guide that should appeal to anyone with a serious interest in coastal habitats.

Analyzing the economic, political, social, and scientific changes on which the British sailed to power, Tides of History shows how the British Admiralty collaborated closely not only with scholars, such as William Whewell, but also with the maritime community —sailors, local tide table makers, dockyard officials, and harbormasters—in order to systematize knowledge of the world’s oceans, coasts, ports, and estuaries. As Michael S. Reidy points out, Britain’s security and prosperity as a maritime nation depended on its ability to maneuver through the oceans and dominate coasts and channels. The practice of science and the rise of the scientist became inextricably linked to the process of European expansion.

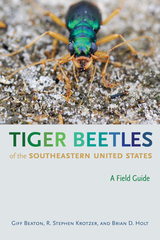

Tiger beetles are brightly colored and metallic beetles, often with ivory or cream-colored markings. They are most abundant and diverse in habitats near bodies of water with sandy or clay soils and can be found along rivers, on sea and lake shores, on sand dunes, around dry lakebeds, on clay banks, or on woodland paths. Conservatively estimated, the group comprises more than 2,600 species worldwide.

Tiger Beetles of the Southeastern United States identifies and describes 52 taxa (42 species and 10 additional subspecies) of tiger beetles that occur in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. Stunning close-up photographs accompany current taxonomic and biological information in a volume designed for a growing audience of enthusiastic amateurs and professionals alike.

The authors provide an in-depth description of the anatomy, life cycle, and behavior of tiger beetles; an overview of the various southeastern habitats in which they occur; instructions for finding, identifying, and photographing them in the wild; and the conservation status of various species. The individual species accounts include stunning, detailed images, flight season charts, county-level regional distribution maps, and discussion of identifying features, habitat, similar species, and subspecies when applicable. The appendix includes two species previously found in Florida but no longer known to exist there.

The result is the most complete field guide to date on tiger beetles in the region. With more than 230 images of beetles and their habitats, as well as life history and distribution data, this book is essential for tiger beetle enthusiasts, naturalists of all kinds, photographers, biologists, and teachers throughout the region.

In parts of Korea and China, moon bears, black but for the crescent-shaped patch of white on their chests, are captured in the wild and brought to "bear farms" where they are imprisoned in squeeze cages, and a steel catheter is inserted into their gall bladders. The dripping bile is collected as a cure for ailments ranging from an upset stomach to skin burns. The bear may live as long as fifteen years in this state. Rhinos are being illegally poached for their horns, as are tigers for their bones, thought to improve virility. Booming economies and growing wealth in parts of Asia are increasing demand for these precious medicinals. Already endangered species are being sacrificed for temporary treatments for nausea and erectile dysfunction.

Richard Ellis, one of the world's foremost experts in wildlife extinction, brings his alarm to the pages of Tiger Bone & Rhino Horn, in the hope that through an exposure of this drug trade, something can be done to save the animals most direly threatened. Trade in animal parts for traditional Chinese medicine is a leading cause of species endangerment in Asia, and poaching is increasing at an alarming rate. Most of traditional Chinese medicine relies on herbs and other plants, and is not a cause for concern. Ellis illuminates those aspects of traditional medicine, but as wildlife habitats are shrinking for the hunted large species, the situation is becoming ever more critical.

One hundred years ago, there were probably 100,000 tigers in India, South China, Sumatra, Bali, Java, and the Russian Far East. The South Chinese, Caspian, Balinese, and Javan species are extinct. There are now fewer than 5,000 tigers in all of India, and the numbers are dropping fast. There are five species of rhinoceros--three in Asia and two in Africa--and all have been hunted to near extinction so their horns can be ground into powder, not for aphrodisiacs, as commonly thought, but for ailments ranging from arthritis to depression. In 1930, there were 80,000 black rhinos in Africa. Now there are fewer than 2,500.

Tigers, bears, and rhinos are not the only animals pursued for the sake of alleviating human ills--the list includes musk deer, sharks, saiga antelope, seahorses, porcupines, monkeys, beavers, and sea lions--but the dwindling numbers of those rare species call us to attention. Ellis tells us what has been done successfully, and contemplates what can and must be done to save these animals or, sadly, our children will witness the extinction of tigers, rhinos, and moon bears in their lifetime.

What is time? Is there a link between objective knowledge about time and subjective experience of time? And what is eternity? Does religion have the answer? Does science?

•Theological approaches to time and eternity, as well as a look at Trinitarian theology and its relation to time

•The discussion of scientific theories of time, including Newtonian, relativistic, quantum, and chaos theories

•The formulation of a "theology of time," a theological-mathematical model incorporating relational thinking oriented toward the future, the doctrine of trinity, and the notion of eschatology

This book is an attempt to get to the bottom of an acute and perennial tension between our best scientific pictures of the fundamental physical structure of the world and our everyday empirical experience of it. The trouble is about the direction of time. The situation (very briefly) is that it is a consequence of almost every one of those fundamental scientific pictures--and that it is at the same time radically at odds with our common sense--that whatever can happen can just as naturally happen backwards.

Albert provides an unprecedentedly clear, lively, and systematic new account--in the context of a Newtonian-Mechanical picture of the world--of the ultimate origins of the statistical regularities we see around us, of the temporal irreversibility of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, of the asymmetries in our epistemic access to the past and the future, and of our conviction that by acting now we can affect the future but not the past. Then, in the final section of the book, he generalizes the Newtonian picture to the quantum-mechanical case and (most interestingly) suggests a very deep potential connection between the problem of the direction of time and the quantum-mechanical measurement problem.

The book aims to be both an original contribution to the present scientific and philosophical understanding of these matters at the most advanced level, and something in the nature of an elementary textbook on the subject accessible to interested high-school students.

Winner of the Runciman Award

Winner of the Charles J. Goodwin Award

“Tells the story of how the Seleucid Empire revolutionized chronology by picking a Year One and counting from there, rather than starting a new count, as other states did, each time a new monarch was crowned…Fascinating.”

—Harper’s

In the aftermath of Alexander the Great’s conquests, his successors, the Seleucid kings, ruled a vast territory stretching from Central Asia and Anatolia to the Persian Gulf. In 305 BCE, in a radical move to impose unity and regulate behavior, Seleucus I introduced a linear conception of time. Time would no longer restart with each new monarch. Instead, progressively numbered years—continuous and irreversible—became the de facto measure of historical duration. This new temporality, propagated throughout the empire and identical to the system we use today, changed how people did business, recorded events, and oriented themselves to the larger world.

Some rebellious subjects, eager to resurrect their pre-Hellenic past, rejected this new approach and created apocalyptic time frames, predicting the total end of history. In this magisterial work, Paul Kosmin shows how the Seleucid Empire’s invention of a new kind of time—and the rebellions against this worldview—had far reaching political and religious consequences, transforming the way we organize our thoughts about the past, present, and future.

“Without Paul Kosmin’s meticulous investigation of what Seleucus achieved in creating his calendar without end we would never have been able to comprehend the traces of it that appear in late antiquity…A magisterial contribution to this hitherto obscure but clearly important restructuring of time in the ancient Mediterranean world.”

—G. W. Bowersock, New York Review of Books

“With erudition, theoretical sophistication, and meticulous discussion of the sources, Paul Kosmin sheds new light on the meaning of time, memory, and identity in a multicultural setting.”

—Angelos Chaniotis, author of Age of Conquests

Who were the first people to inhabit North America? Does the West Bank belong to the Arabs or the Jews? Why are racists so obsessed with origins? Is a seventh cousin still a cousin? Why do some societies name their children after dead ancestors?

As Eviatar Zerubavel demonstrates in Time Maps, we cannot answer burning questions such as these without a deeper understanding of how we envision the past. In a pioneering attempt to map the structure of our collective memory, Zerubavel considers the cognitive patterns we use to organize the past in our minds and the mental strategies that help us string together unrelated events into coherent and meaningful narratives, as well as the social grammar of battles over conflicting interpretations of history. Drawing on fascinating examples that range from Hiroshima to the Holocaust, from Columbus to Lucy, and from ancient Egypt to the former Yugoslavia, Zerubavel shows how we construct historical origins; how we tie discontinuous events together into stories; how we link families and entire nations through genealogies; and how we separate distinct historical periods from one another through watersheds, such as the invention of fire or the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Most people think the Roman Empire ended in 476, even though it lasted another 977 years in Byzantium. Challenging such conventional wisdom, Time Maps will be must reading for anyone interested in how the history of our world takes shape.

To see video demonstrations of key concepts from the book, please visit this website: http://www.press.uchicago.edu/sites/timewarp/

Sci-fi makes it look so easy. Receive a distress call from Alpha Centauri? No problem: punch the warp drive and you're there in minutes. Facing a catastrophe that can't be averted? Just pop back in the timestream and stop it before it starts. But for those of us not lucky enough to live in a science-fictional universe, are these ideas merely flights of fancy—or could it really be possible to travel through time or take shortcuts between stars?

Cutting-edge physics may not be able to answer those questions yet, but it does offer up some tantalizing possibilities. In Time Travel and Warp Drives, Allen Everett and Thomas A. Roman take readers on a clear, concise tour of our current understanding of the nature of time and space—and whether or not we might be able to bend them to our will. Using no math beyond high school algebra, the authors lay out an approachable explanation of Einstein's special relativity, then move through the fundamental differences between traveling forward and backward in time and the surprising theoretical connection between going back in time and traveling faster than the speed of light. They survey a variety of possible time machines and warp drives, including wormholes and warp bubbles, and, in a dizzyingly creative chapter, imagine the paradoxes that could plague a world where time travel was possible—killing your own grandfather is only one of them!

Written with a light touch and an irrepressible love of the fun of sci-fi scenarios—but firmly rooted in the most up-to-date science, Time Travel and Warp Drives will be a delightful discovery for any science buff or armchair chrononaut.

Out of their discoveries, new histories emerged, giving rise to fresh debates, while seemingly well-known histories were thrown into confusion by novel tools and methods of scrutiny. If in the eighteenth century the study of the past had been the province of a handful of elites, new technologies and economic development in the nineteenth century meant that the past, in all its brilliant detail, was for the first time the property of the many, not the few. Time Travelers is a book about the myriad ways in which Victorians approached the past, offering a vivid picture of the Victorian world and its historical obsessions.

Rarely has a scholar attained such popular acclaim merely by doing what he does best and enjoys most. But such is Stephen Jay Gould’s command of paleontology and evolutionary theory, and his gift for brilliant explication, that he has brought dust and dead bones to life, and developed an immense following for the seeming arcana of this field.

In Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle his subject is nothing less than geology’s signal contribution to human thought—the discovery of “deep time,” the vastness of earth’s history, a history so ancient that we can comprehend it only as metaphor. He follows a single thread through three documents that mark the transition in our thinking from thousands to billions of years: Thomas Burnet’s four-volume Sacred Theory of the Earth (1680–1690), James Hutton’s Theory of the Earth (1795), and Charles Lyell’s three-volume Principles of Geology (1830–1833).

Gould’s major theme is the role of metaphor in the formulation and testing of scientific theories—in this case the insight provided by the oldest traditional dichotomy of Judeo-Christian thought: the directionality of time’s arrow or the immanence of time’s cycle. Gould follows these metaphors through these three great documents and shows how their influence, more than the empirical observation of rocks in the field, provoked the supposed discovery of deep time by Hutton and Lyell. Gould breaks through the traditional “cardboard” history of geological textbooks (the progressive march to truth inspired by more and better observations) by showing that Burnet, the villain of conventional accounts, was a rationalist (not a theologically driven miracle-monger) whose rich reconstruction of earth history emphasized the need for both time’s arrow (narrative history) and time’s cycle (immanent laws), while Hutton and Lyell, our traditional heroes, denied the richness of history by their exclusive focus upon time’s arrow.

Most people, when they contemplate the living world, conclude that it is a designed place. So it is jarring when biologists come along and say this is all wrong. What most people see as design, they say--purposeful, directed, even intelligent--is only an illusion, something cooked up in a mind that is eager to see purpose where none exists. In these days of increasingly assertive challenges to Darwinism, the question becomes acute: is our perception of design simply a mental figment, or is there something deeper at work?

Physiologist Scott Turner argues eloquently and convincingly that the apparent design we see in the living world only makes sense when we add to Darwin's towering achievement the dimension that much modern molecular biology has left on the gene-splicing floor: the dynamic interaction between living organisms and their environment. Only when we add environmental physiology to natural selection can we begin to understand the beautiful fit between the form life takes and how life works.

In The Tinkerer's Accomplice, Scott Turner takes up the question of design as a very real problem in biology; his solution poses challenges to all sides in this critical debate.

To Care for Creation chronicles this movement and explains how it has emerged despite institutional and cultural barriers, as well as the hurdles posed by logic and practices that set religious environmental organizations apart from the secular movement. Ellingson takes a deep dive into the ways entrepreneurial activists tap into and improvise on a variety of theological, ethical, and symbolic traditions in order to issue a compelling call to arms that mobilizes religious audiences. Drawing on interviews with the leaders of more than sixty of these organizations, Ellingson deftly illustrates how activists borrow and rework resources from various traditions to create new meanings for religion, nature, and the religious person’s duty to the natural world.

When the national park system was first established in 1916, the goal "to conserve unimpaired" seemed straightforward. But Robert Keiter argues that parks have always served a variety of competing purposes, from wildlife protection and scientific discovery to tourism and commercial development. In this trenchant analysis, he explains how parks must be managed more effectively to meet increasing demands in the face of climate, environmental, and demographic changes.

Taking a topical approach, Keiter traces the history of the national park idea from its inception to its uncertain future. Thematic chapters explore our changing conceptions of the parks as wilderness sanctuaries, playgrounds, educational facilities, and more. He also examines key controversies that have shaped the parks and our perception of them.

Ultimately, Keiter demonstrates that parks cannot be treated as special islands, but must be managed as the critical cores of larger ecosystems. Only when the National Park Service works with surrounding areas can the parks meet critical habitat, large-scale connectivity, clean air and water needs, and also provide sanctuaries where people can experience nature. Today's mandate must remain to conserve unimpaired—but Keiter shows how the national park idea can and must go much farther.

Professionals, students, and scholars with an interest in environmental history, national parks, and federal land management, as well as scientists and managers working on adaptation to climate change should find the book useful and inspiring.

When planes crash, bridges collapse, and automobile gas tanks explode, we are quick to blame poor design. But Henry Petroski says we must look beyond design for causes and corrections. Known for his masterly explanations of engineering successes and failures, Petroski here takes his analysis a step further, to consider the larger context in which accidents occur.

In To Forgive Design he surveys some of the most infamous failures of our time, from the 2007 Minneapolis bridge collapse and the toppling of a massive Shanghai apartment building in 2009 to Boston's prolonged Big Dig and the 2010 Gulf oil spill. These avoidable disasters reveal the interdependency of people and machines within systems whose complex behavior was undreamt of by their designers, until it was too late. Petroski shows that even the simplest technology is embedded in cultural and socioeconomic constraints, complications, and contradictions.

Failure to imagine the possibility of failure is the most profound mistake engineers can make. Software developers realized this early on and looked outside their young field, to structural engineering, as they sought a historical perspective to help them identify their own potential mistakes. By explaining the interconnectedness of technology and culture and the dangers that can emerge from complexity, Petroski demonstrates that we would all do well to follow their lead.

"A welcome contribution to the history of science in the South during the period since the Civil War. . . . By considering the academies in the larger context of scientific professionalism, South and North, Midgette has produced a surprisingly wide-ranging and informative study. This is overall a judicious and carefully researched work. The writing is straightforward and admirably clear, while the topic is effectively organized and presented. The book is a commendably original addition to local and regional history as well as history of American Science."

—Journal of American History

"Midgette’s study is thorough and well organized and should be consulted by anyone interested in American science and American higher education."

—Florida Historical Quarterly

"A very useful survey."

—Choice

Duhem's 1908 essay questions the relation between physical theory and metaphysics and, more specifically, between astronomy and physics–an issue still of importance today. He critiques the answers given by Greek thought, Arabic science, medieval Christian scholasticism, and, finally, the astronomers of the Renaissance.

From boreal Alaska to subtropical Florida, from the chaparral of California to the pitch pine of New Jersey, America boasts nearly a billion burnable acres. In nine previous volumes, Stephen J. Pyne has explored the fascinating variety of flame region by region. In To the Last Smoke: An Anthology, he selects a sampling of the best from each.

To the Last Smoke offers a unique and sweeping view of the nation’s fire scene by distilling observations on Florida, California, the Northern Rockies, the Great Plains, the Southwest, the Interior West, the Northeast, Alaska, the oak woodlands, and the Pacific Northwest into a single, readable volume. The anthology functions as a color-commentary companion to the play-by-play narrative offered in Pyne’s Between Two Fires: A Fire History of Contemporary America. The series is Pyne’s way of “keeping with it to the end,” encompassing the directive from his rookie season to stay with every fire “to the last smoke.”

A new classic of science reporting.”—The New York Times

The true story of a small town ravaged by industrial pollution, Toms River won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize and has been hailed by The New York Times as "a new classic of science reporting." Now available in paperback with a new afterword by acclaimed author Dan Fagin, the book masterfully blends hard-hitting investigative journalism, scientific discovery, and unforgettable characters.

One of New Jersey’s seemingly innumerable quiet seaside towns, Toms River became the unlikely setting for a decades-long drama that culminated in 2001 with one of the largest environmental legal settlements in history. For years, large chemical companies had been using Toms River as their private dumping ground, burying tens of thousands of leaky drums in open pits and discharging billions of gallons of acid-laced wastewater into the town’s namesake river. The result was a notorious cluster of childhood cancers scientifically linked to local air and water pollution.

Fagin recounts the sixty-year saga of rampant pollution and inadequate oversight that made Toms River a cautionary tale. He brings to life the pioneering scientists and physicians who first identified pollutants as a cause of cancer and the everyday people in Toms River who struggled for justice: a young boy whose cherubic smile belied the fast-growing tumors that had decimated his body from birth; a nurse who fought to bring the alarming incidence of childhood cancers to the attention of authorities who didn’t want to listen; and a mother whose love for her stricken child transformed her into a tenacious advocate for change.

Rooted in a centuries-old scientific quest, Toms River is an epic of dumpers at midnight and deceptions in broad daylight, of corporate avarice and government neglect, and of a few brave individuals who refused to keep silent until the truth was exposed.

Medicine is itself a type of technology, involving therapeutic tools and substances, and so one can write the history of medicine as the application of different technologies to the human body. In Tools and the Organism, Colin Webster argues that, throughout antiquity, these tools were crucial to broader theoretical shifts. Notions changed about what type of object a body is, what substances constitute its essential nature, and how its parts interact. By following these changes and taking the question of technology into the heart of Greek and Roman medicine, Webster reveals how the body was first conceptualized as an “organism”—a functional object whose inner parts were tools, or organa, that each completed certain vital tasks. He also shows how different medical tools created different bodies.

Webster’s approach provides both an overarching survey of the ways that technologies impacted notions of corporeality and corporeal behaviors and, at the same time, stays attentive to the specific material details of ancient tools and how they informed assumptions about somatic structures, substances, and inner processes. For example, by turning to developments in water-delivery technologies and pneumatic tools, we see how these changing material realities altered theories of the vascular system and respiration across Classical antiquity. Tools and the Organism makes the compelling case for why telling the history of ancient Greco-Roman medical theories, from the Hippocratics to Galen, should pay close attention to the question of technology.

The Forest Service stumbled in responding to a wave of lawsuits from environmental groups in the late 20th Century—a phenomenon best symbolized by the spotted owl controversy that shut down logging on public forests in the Pacific Northwest in the 1990s. The agency was brought to its knees, pitted between a powerful timber industry that had been having its way with the national forests for decades, and organized environmentalists who believed public lands had been abused and deserved better stewardship.

Toward a Natural Forest offers an insider’s view of this tumultuous time in the history of the Forest Service, presenting twin tales of transformation, both within the agency and within the author’s evolving environmental consciousness. While stewarding our national forests with the best of intentions, had the Forest Service diminished their natural essence and ecological values? How could one man confront the crisis while remaining loyal to his employer?

In this revealing memoir, Furnish addresses the fundamental human drive to gain sustenance from and protect the Earth, believing that we need not destroy it in the process. Drawing on the author’s personal experience and his broad professional knowledge, Toward a Natural Forest illuminates the potential of the Forest Service to provide strong leadership in global conservation efforts. Those interested in our public lands—environmentalists, natural resource professionals, academics, and historians—will find Jim Furnish’s story deeply informed, thought-provoking, and ultimately inspiring.

In this forcefully argued book, the leading evolutionary theorist of language draws on evidence from evolutionary biology, genetics, physical anthropology, anatomy, and neuroscience, to provide a framework for studying the evolution of human language and cognition.

Philip Lieberman argues forcibly that the widely influential theories of language's development, advanced by Chomskian linguists and cognitive scientists, especially those that postulate a single dedicated language "module," "organ," or "instinct," are inconsistent with principles and findings of evolutionary biology and neuroscience. He argues that the human neural system in its totality is the basis for the human language ability, for it requires the coordination of neural circuits that regulate motor control with memory and higher cognitive functions. Pointing out that articulate speech is a remarkably efficient means of conveying information, Lieberman also highlights the adaptive significance of the human tongue.

Fully human language involves the species-specific anatomy of speech, together with the neural capacity for thought and movement. In Lieberman's iconoclastic Darwinian view, the human language ability is the confluence of a succession of separate evolutionary developments, jury-rigged by natural selection to work together for an evolutionarily unique ability.

An interdisciplinary environmental humanities volume that explores human-environment relationships on our permanently polluted planet.

While toxicity and pollution are ever present in modern daily life, politicians, juridical systems, media outlets, scholars, and the public alike show great difficulty in detecting, defining, monitoring, or generally coming to terms with them. This volume’s contributors argue that the source of this difficulty lies in the struggle to make sense of the intersecting temporal and spatial scales working on the human and more-than-human body, while continuing to acknowledge race, class, and gender in terms of global environmental justice and social inequality.

The term toxic timescapes refers to this intricate intersectionality of time, space, and bodies in relation to toxic exposure. As a tool of analysis, it unpacks linear understandings of time and explores how harmful substances permeate temporal and physical space as both event and process. It equips scholars with new ways of creating data and conceptualizing the past, present, and future presence and possible effects of harmful substances and provides a theoretical framework for new environmental narratives. To think in terms of toxic timescapes is to radically shift our understanding of toxicants in the complex web of life.

Toxicity, pollution, and modes of exposure are never static; therefore, dose, timing, velocity, mixture, frequency, and chronology matter as much as the geographic location and societal position of those exposed. Together, these factors create a specific toxic timescape that lies at the heart of each contributor’s narrative. Contributors from the disciplines of history, human geography, science and technology studies, philosophy, and political ecology come together to demonstrate the complex reality of a toxic existence. Their case studies span the globe as they observe the intersection of multiple times and spaces at such diverse locations as former battlefields in Vietnam, aging nuclear-weapon storage facilities in Greenland, waste deposits in southern Italy, chemical facilities along the Gulf of Mexico, and coral-breeding laboratories across the world.

Paul Shepard is one of the most profound and original thinkers of our time. He has helped define the field of human ecology, and has played a vital role in the development of what have come to be known as environmental philosophy, ecophilosophy, and deep ecology -- new ways of thinking about human-environment interactions that ultimately hold great promise for healing the bonds between humans and the natural world. Traces of an Omnivore presents a readable and accessible introduction to this seminal thinker and writer.

Throughout his long and distinguished career, Paul Shepard has addressed the most fundamental question of life: Who are we? An oft-repeated theme of his writing is what he sees as the central fact of our existence: that our genetic heritage, formed by three million years of hunting and gathering remains essentially unchanged. Shepard argues that this, "our wild Pleistocene genome," influences everything from human neurology and ontogeny to our pathologies, social structure, myths, and cosmology.

While Shepard's writings travel widely across the intellectual landscape, exploring topics as diverse as aesthetics, the bear, hunting, perception, agriculture, human ontogeny, history, animal rights, domestication, post-modern deconstruction, tourism, vegetarianism, the iconography of animals, the Hudson River school of painters, human ecology, theoretical psychology, and metaphysics, the fundamental importance of our genetic makeup is the predominant theme of this collection.

As Jack Turner states in an eloquent and enlightening introduction, the essays gathered here "address controversy with an intellectual courage uncommon in an age that exults the relativist, the skeptic, and the cynic. Perused with care they will reward the reader with a deepened appreciation of what we so casually denigrate as primitive life -- the only life we have in the only world we will ever know."

In demystifying the old and new Europe across a multiplicity of texts, images, media, and cultural practices in various times and locations, Verstraete lays bare a territorial persistence in the European imaginary, one which has been differently tied up with the politics of inclusion and exclusion. Tracking Europe moves from policy papers, cultural tourism, and migration to philosophies of cosmopolitanism, nineteenth-century travel guides, electronic surveillance at the border, virtual pilgrimages to Spain, and artistic interventions in the Balkan region. It is a sustained attempt to situate current developments in Europe within a complex matrix of tourism, migration, and border control, as well as history, poststructuralist theory, and critical media and art projects.

Tracks in Deep Time presents, for the first time, an engaging, thoroughly readable account of the history, geology, and paleontology of this important site. Two hundred million years ago, Lake Dixie covered the site. Within its waters and along its shores, a diverse ecosystem of dinosaurs, early crocodylians, fishes, plants, and other organisms thrived, leaving behind thousands of footprints and other fossils preserved in layers of rock. Unusual fossils found here include the world’s largest collection of tracks left by swimming dinosaurs and one of only six traces known to have been made by a sitting, meat-eating dinosaur. With approachable text and lavish, full-color photographs and illustrations, Jerald Harris and Andrew Milner describe how geologists and paleontologists have painstakingly reconstructed a vivid “snapshot” of life from the Early Jurassic epoch.

Prior to the First World War, more people learned of evolutionary theory from the voluminous writings of Charles Darwin’s foremost champion in Germany, Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), than from any other source, including the writings of Darwin himself. But, with detractors ranging from paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould to modern-day creationists and advocates of intelligent design, Haeckel is better known as a divisive figure than as a pioneering biologist. Robert J. Richards’s intellectual biography rehabilitates Haeckel, providing the most accurate measure of his science and art yet written, as well as a moving account of Haeckel’s eventful life.

How are we to think and act constructively in the face of today’s environmental and political catastrophes? Gail Stenstad finds inspiring answers in the thought of German philosopher Martin Heidegger. Rather than simply describing or explaining Heidegger’s transformative way of thinking, Stenstad’s writing enacts it, bringing new insight into contemporary environmental, political, and personal issues. Readers come to understand some of Heidegger’s most challenging concepts through experiencing them. This is a truly creative scholarly work that invites all readers to carry Heidegger’s transformative thinking into their own areas of deep concern.

"If you have thrown up your hands in despair after trying to retain women science and engineering in the academy, read this book. It offers detailed descriptions of a wide array of tried-and-true programs that have been tested out by the NSF ADVANCE program."

---Joan C. Williams, 1066 Foundation Chair & Distinguished Professor of Law Director, Center for WorkLife Law University of California

"Solid and practical, this volume details the first years of NSF funded institutional change to remake gender dynamics inside U.S. science. What works? What doesn't? And why?"

---Londa Schiebinger, John L. Hinds Professor of History of Science and Barbara D. Finberg Director, Michelle R. Clayman Institute for Gender Research at Stanford University, and author of Has Feminism Changed Science?

"This book's time has come. Transforming Science and Engineering is important, and lots of people can learn from what has happened in the ADVANCE universities."

---Lotte Bailyn, Professor of Management, Behavioral and Policy Sciences Department, Sloan School of Management, MIT; author of Breaking the Mold: Redesigning Work for Productive and Satisfying Lives; and coauthor of Beyond Work-Family Balance: Advancing Gender Equity and Workplace Performance

"This collection profiles 16 NSF ADVANCE grant successes, sandwiched between an interview with Dr. Alice Hogan and Dr. Lee Harle's summary of cost-effective practices from ADVANCE programs, giving so many 'biggest bang for the buck' examples in so few pages that it will easily justify both the cost of the book and the reading time. These accounts do not continue the too-common vague referrals to 'unhealthy environment' or 'chilly climate,' but rather expound the situations before and after the interventions, something necessary in order to transplant the programs, or even to use the programs for idea generation. Transforming Science and Engineering is a model of excellence, and will be extremely useful for those women, men, faculty, or administrators wanting to help their universities move into the 21st century and attract to their campuses qualified women and men who want opportunities to attain their full potentials."

---Donna J. Nelson, Associate Professor of Chemistry, University of Oklahoma

In 2001, the National Science Foundation's ADVANCE Institutional Transformation program began awarding five-year grants to colleges and universities to address a common problem: how to improve the work environment for women faculty in science and engineering. Drawing on the expertise of scientists, engineers, social scientists, specialists in organizational behavior, and university administrators, this collection is the first to describe the variety of innovative efforts academic institutions around the country have undertaken.

Focusing on a wide range of topics, from how to foster women's academic success in small teaching institutions, to how to use interactive theater to promote faculty reflection about departmental culture, to how a particular department created and maintained a healthy climate for women's scientific success, the contributors discuss both the theoretical and empirical aspects of the initiatives, with emphasis on the practical issues involved in creating these approaches. The resulting evidence shows that these initiatives have the desired effects. The cases represented in this collection depict the many issues women faculty in science and engineering face, and the solutions that are presented can be widely accepted at academic institutions around the United States. The essays in Transforming Science and Engineering illustrate that creating work environments that sustain and advance women scientists and engineers benefits women, men, and underrepresented minorities.

Abigail J. Stewart is Sandra Schwartz Tangri Distinguished University Professor of Psychology and Women's Studies at the University of Michigan.

Janet E. Malley is a psychologist and Associate Director of the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan.

Danielle LaVaque-Manty, former Research Associate at the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at the University of Michigan, teaches composition at U-M's Sweetland Writing Center.

Cover photo: Joanne Leonard

Transhumanism posits that humanity is on the verge of rapid evolutionary change as a result of emerging technologies and increased global consciousness. However, this insight is dismissed as a naive and controversial reframing of posthumanist thought, having also been vilified as “the most dangerous idea in the world” by Francis Fukuyama. In this book, Andrew Pilsch counters these critiques, arguing instead that transhumanism’s utopian rhetoric actively imagines radical new futures for the species and its habitat.

Pilsch situates contemporary transhumanism within the longer history of a rhetorical mode he calls “evolutionary futurism” that unifies diverse texts, philosophies, and theories of science and technology that anticipate a radical explosion in humanity’s cognitive, physical, and cultural potentialities. By conceptualizing transhumanism as a rhetoric, as opposed to an obscure group of fringe figures, he explores the intersection of three major paradigms shaping contemporary Western intellectual life: cybernetics, evolutionary biology, and spiritualism. In analyzing this collision, his work traces the belief in a digital, evolutionary, and collective future through a broad range of texts written by theologians and mystics, biologists and computer scientists, political philosophers and economic thinkers, conceptual artists and Golden Age science fiction writers. Unearthing the long history of evolutionary futurism, Pilsch concludes, allows us to more clearly see the novel contributions that transhumanism offers for escaping our current geopolitical bind by inspiring radical utopian thought.

Principe, the leading authority on the subject, recounts how Homberg’s radical vision promoted chymistry as the most powerful and reliable means of understanding the natural world. Homberg’s work at the Académie and in collaboration with the future regent, Philippe II d’Orléans, as revealed by a wealth of newly uncovered documents, provides surprising new insights into the broader changes chymistry underwent during, and immediately after, Homberg. A human, disciplinary, and institutional biography, The Transmutations of Chymistry significantly revises what was previously known about the contours of chymistry and scientific institutions in the early eighteenth century.

In a book that is bound to ignite controversy, Ruth Leys investigates the history of the concept of trauma. She explores the emergence of multiple personality disorder, Freud's approaches to trauma, medical responses to shellshock and combat fatigue, Sándor Ferenczi's revisions of psychoanalysis, and the mutually reinforcing, often problematic work of certain contemporary neurobiological and postmodernist theorists. Leys argues that the concept of trauma has always been fundamentally unstable, oscillating uncontrollably between two competing models, each of which tends at its limit to collapse into the other.

A powerfully argued work of intellectual history, Trauma will rewrite the terms of future discussion of its subject.

Driving across I-70 in southern Utah one can’t help but wonder about the magnificent upturned rocks of the San Rafael Reef. With A Travelers Guide to the Geology of the Colorado Plateau in hand, you’ll soon discover that you were driving through Page and Navajo Sandstone formations, sharply folded into a monocline along one of the "Basin and Range" fault lines. Nearing Flagstaff, Arizona, on Highway 89, you will learn that Mt. Humphry of the San Francisco Peaks, a Navajo Sacred Mountain, was once an active volcano. Keep reading and you’ll find many things worth a slight detour.

A Traveler's Guide to the Geology of the Colorado Plateau will enrich and enliven all of your trips through the varied landscapes of the Colorado Plateau as you learn about the geological forces that have shaped its natural features. The mile-by-mile road logs will take you from Vernal, Utah, in the north to the southernmost reaches of the Plateau in Sedona, Arizona; from the red rocks of Cedar Breaks National Monument near Cedar City, Utah, to the edges of the soaring peaks of the San Juan Mountains near Durango, Colorado. The most comprehensive geological guide to the Colorado Plateau

From the sixteenth century until the early nineteenth, Europeans had envisioned New Spain (colonial Mexico) in texts, maps, and other images. In the first decades of the 1800s, ideas about Mexican, rather than Spanish, national character and identity began to cohere in written and illustrated narratives produced by foreign travelers. During the nineteenth century, technologies and processes of visual reproduction expanded to include lithography, daguerreotype, and photography. New methods of display—such as albums, museums, exhibitions, and world fairs—signaled new ideas about spectatorship. García Cubas participated in this emerging visual culture as he reconfigured geographic and cultural imagery culled from previous mapping practices and travel writing. In works such as the Atlas geográfico (1858) and the Atlas pintoresco é historico (1885), he presented independent Mexico to Mexican citizens and the world.

With genetically modified crops we have entered uncharted territory—where visions of the triumph of biotechnology in agriculture vie with dire views of medical and environmental disaster. For two years Mark L. Winston traveled this fraught territory at home and abroad, listening to farmers, industry spokespeople, regulators, and researchers, canvassing high-security laboratories, environmentalist enclaves, and cyberspace, making a thorough survey of the facts, opinions, and practices deployed by opponents and proponents of transgenic crops.

Through his sympathetic portrayal of the passions on all sides, Winston brings a clear, unbiased perspective to this bewildering landscape. Traveling with Winston, we see the excitement and curiosity that pervade laboratories developing genetically modified crops, as well as the panic and outrage among dedicated opponents of agricultural biotechnology; the desperation of conventional farmers as they look to science for solutions to the problems driving them from their farms, as well as the deeply held values of organic farmers who dread the incursion of genetically modified crops into their expanding enterprise. And, Winston shows us, these contrasting attitudes transcend national borders, with troubling counterparts and consequences in the developing world.

As he seeks a middle ground where concerns about genetic engineering can be rationally discussed and resolved, Winston gives us, at long last, a full and balanced view of the forces at play in the chaotic debate over agricultural biotechnology.

Drawing on detailed examination of the John Murray Archive of manuscripts, images, and the firm’s correspondence with its many authors—a list that included such illustrious explorers and scientists as Charles Darwin and Charles Lyell, and literary giants like Jane Austen, Lord Byron, and Sir Walter Scott—Travels into Print considers how journeys of exploration became published accounts and how travelers sought to demonstrate the faithfulness of their written testimony and to secure their personal credibility. This fascinating study in historical geography and book history takes modern readers on a journey into the nature of exploration, the production of authority in published travel narratives, and the creation of geographical authorship—a journey bound together by the unifying force of a world-leading publisher.

Creative expression inspired by disease has been criticized as a celebration of victimhood, unmediated personal experience, or just simply bad art. Despite debate, however, memoirs written about illness—particularly AIDS or cancer—have proliferated since the late twentieth century and occupy a highly influential place on the cultural landscape today.

In Treatments, Lisa Diedrich considers illness narratives, demonstrating that these texts not only recount and interpret symptoms but also describe illness as an event that reflects wider cultural contexts, including race, gender, class, and sexuality. Diedrich begins this theoretically rigorous analysis by offering examples of midcentury memoirs of tuberculosis. She then looks at Susan Sontag’s Illness As Metaphor, Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals, and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s “White Glasses,” showing how these breast cancer survivors draw on feminist health practices of the 1970s and also anticipate the figure that would appear in the wake of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s—the “politicized patient.” She further reveals how narratives written by doctors Abraham Verghese and Rafael Campo about treating people with AIDS can disrupt the doctor–patient hierarchy, and she explores practices of witnessing that emerge in writing by Paul Monette and John Bayley.

Through these records of intensely personal yet universal experience, Diedrich demonstrates how language both captures and fails to capture these “scenes of loss” and how illness narratives affect the literary, medical, and cultural contexts from which they arise. Finally, by examining the ways in which the sick speak and are spoken for, she argues for an ethics of failure—the revaluation of loss as creating new possibilities for how we live and die.

Lisa Diedrich is assistant professor of women’s studies at Stony Brook University.

Did you know that you are more closely related to a mushroom than to a daisy? That crocodiles are closer to birds than to lizards? That dinosaurs are still among us? That the terms "fish," "reptiles," and "invertebrates" do not indicate scientific groupings? All this is the result of major changes in classification, whose methods have been totally revisited over the last thirty years.

Modern classification, based on phylogeny, no longer places humans at the center of nature. Groups of organisms are no longer defined by their general appearance, but by their different individual characteristics. Phylogeny, therefore, by showing common ancestry, outlines a tree of evolutionary relationships from which one can retrace the history of life.

This book diagrams the tree of life according to the most recent methods of classification. By showing how life forms arose and developed and how they are related, The Tree of Life presents a key to the living world in all its dazzling variety.,

How did we become the linguistic, cultured, and hugely successful apes that we are? Our closest relatives--the other mentally complex and socially skilled primates--offer tantalizing clues. In Tree of Origin nine of the world's top primate experts read these clues and compose the most extensive picture to date of what the behavior of monkeys and apes can tell us about our own evolution as a species.

It has been nearly fifteen years since a single volume addressed the issue of human evolution from a primate perspective, and in that time we have witnessed explosive growth in research on the subject. Tree of Origin gives us the latest news about bonobos, the "make love not war" apes who behave so dramatically unlike chimpanzees. We learn about the tool traditions and social customs that set each ape community apart. We see how DNA analysis is revolutionizing our understanding of paternity, intergroup migration, and reproductive success. And we confront intriguing discoveries about primate hunting behavior, politics, cognition, diet, and the evolution of language and intelligence that challenge claims of human uniqueness in new and subtle ways.

Tree of Origin provides the clearest glimpse yet of the apelike ancestor who left the forest and began the long journey toward modern humanity.

Trees and Forests of Tropical Asia invites readers on an expedition into the leafy, humid, forested landscapes of tropical Asia—the so-called tapovan, a Sanskrit word for the forest where knowledge is attained through tapasya, or inner struggle. Peter Ashton and David Lee, two of the world’s leading scholars on Asian tropical rain forests, reveal the geology and climate that have produced these unique forests, the diversity of species that inhabit them, the means by which rain forest tree species evolve to achieve unique ecological space, and the role of humans in modifying the landscapes over centuries. Following Peter Ashton’s extensive On the Forests of Tropical Asia, the first book to describe the forests of the entire tropical Asian region from India east to New Guinea, this new book provides a more condensed and updated overview of tropical Asian forests written accessibly for students as well as tropical forest biologists, ecologists, and conservation biologists.

Trees seen like never before—a world expert presents a stunning compendium, illuminating science, conservation, and art.

Trees provoke deep affection, spirituality, and creativity. They cover about a third of the world’s land and play a crucial role in our environmental systems—influencing the water, carbon, and nutrient cycles and the global climate. This puts trees at the forefront of research into mitigating our climate emergency; we cannot understate their importance in shaping our daily lives and our planet’s future.

In these lavish pages, ecologist Paul Smith celebrates all that trees have inspired across nearly every human culture throughout history. Generously illustrated with over 450 images and organized according to tree life cycle—from seeds and leaves to wood, flowers, and fruit—this book celebrates the great diversity and beauty of the 60,000 tree species that inhabit our planet. Surprising photography and infographics will inspire readers, illustrating intricate bark and leaf patterns, intertwined ecosystems, colorful flower displays, archaic wooden wheels, and timber houses. In this lavishly illustrated book, Smith presents the science, art, and culture of trees. As we discover the fundamental and fragile nature of trees and their interdependence, we more deeply understand the forest without losing sight of the magnificent trees.

From the understory flowering dogwood presenting its showy array of white bracts in spring, to the stately, towering baldcypress anchoring swampland with their reddish buttresses; from aromatic groves of Atlantic white-cedar that grow in coastal bogs to the upland rarity of the fire-dependent montane longleaf pine, Alabama is blessed with a staggering diversity of tree species. Trees of Alabama offers an accessible guide to the most notable species occurring widely in the state, forming its renewable forest resources and underpinning its rich green blanket of natural beauty.

Lisa J. Samuelson provides a user-friendly identification guide featuring straightforward descriptions and vivid photographs of more than 140 common species of trees. The text explains the habitat and ecology of each species, including its forest associates, human and wildlife uses, common names, and the derivation of its botanical name. With more than 800 full-color photographs illustrating the general form and habitat of each, plus the distinguishing characteristics of its buds, leaves, flowers, fruit, and bark, readers will be able to identify trees quickly. Colored distribution maps detail the range and occurrence of each species grouped by county, and a quick guide highlights key features at a glance.

This book also features a map of forest types, chapters on basic tree biology and terminology (with illustrative line drawings), a spotlight on the plethora of oak species in the state, and a comprehensive index. This is an invaluable resource for biologists, foresters, and educators and a great reference for outdoorspeople and nature enthusiasts in Alabama and throughout the southeastern United States.

New Guinea is the most floristically diverse island in the world, home to nearly 5,000 tree species alone. Trees of New Guinea details each of the 693 plant genera with arborescent members found in New Guinea, covering the entire region including the West Papua and Papua Provinces of Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and the surrounding islands such as New Britain, New Ireland, and Bougainville. The book follows contemporary classifications and is richly illustrated with line drawings and color photographs throughout. Each group has a family description and key to the New Guinea tree genera, followed by a description of each genus, with notes on taxonomy, distribution, ecology, and diagnostic characters. Trees of New Guinea—winner of the Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries Literature’s 2022 Award for Excellence in Botany—is an essential companion for anyone studying or working in the region, including botanists, conservation workers, ecologists, and zoologists.

Because today's decisions are tomorrow's consequences, every small effort makes a difference, but a broader understanding of our environmental problems is necessary to the development of sustainable ecosystem policies. In Trees, Truffles, and Beasts, Chris Maser, Andrew W. Claridge, and James M. Trappe make a compelling case that we must first understand the complexity and interdependency of species and habitats from the microscopic level to the gigantic. Comparing forests in the Pacific Northwestern United States and Southeastern mainland of Australia, the authors show how easily observable speciesùtrees and mammalsùare part of a complicated infrastructure that includes fungi, lichens, and organisms invisible to the naked eye, such as microbes.

Eminently readable, this important book shows that forests are far more complicated than most of us might think, which means simplistic policies will not save them. Understanding the biophysical intricacies of our life-support systems just might.

Drawing on the most recent work of historians, ecologist geographers, botanists, and forestry professionals, Charles Watkins reveals how established ideas about trees—such as the spread of continuous dense forests across the whole of Europe after the Ice Age—have been questioned and even overturned by archaeological and historical research. He shows how concern over woodland loss in Europe is not well founded—especially while tropical forests elsewhere continue to be cleared—and he unpicks the variety of values and meanings different societies have ascribed to the arboreal. Altogether, he provides a comprehensive, interdisciplinary overview of humankind’s interaction with this abused but valuable resource.

A thought-provoking examination of how insights from neuroscience challenge deeply held assumptions about morality and law.

As emerging neuroscientific insights change our understanding of what it means to be human, the law must grapple with monumental questions, both metaphysical and practical. Recent advances pose significant philosophical challenges: how do neuroscientific revelations redefine our conception of morality, and how should the law adjust accordingly?

Trialectic takes account of those advances, arguing that they will challenge normative theory most profoundly. If all sentient beings are the coincidence of mechanical forces, as science suggests, then it follows that the time has come to reevaluate laws grounded in theories dependent on the immaterial that distinguish the mental and emotional from the physical. Legal expert Peter A. Alces contends that such theories are misguided—so misguided that they undermine law and, ultimately, human thriving.

Building on the foundation outlined in his previous work, The Moral Conflict of Law and Neuroscience, Alces further investigates the implications for legal doctrine and practice.

Featuring specimens from Bohemia to Newfoundland, California to the Tucson Gem and Mineral Show, and Wales to the Anti-Atlas Mountains of Morocco, Levi-Setti’s magnificent book reanimates these “butterflies of the seas” in 235 astonishing full-color photographs. All original, Levi-Setti’s images serve as the jumping-off point for tales of his global quests in search of these highly sought-after fossils; for discussions of their mineralogical origins, as revealed by their color; and for unraveling the role of the now-extinct trilobites in our planetary history.

Sure to enthrall paleontologists with its scientific insights and amateur enthusiasts with its beautiful and informative images, The Trilobite Book combines the best of science, technology, aesthetics, and personal adventure. It will inspire new collectors for eras to come.

This second edition features coverage of a greater variety of trilobites, an improved photographic atlas reorganized to present their evolutionary progression, and over 200 photographs.

One of our most brilliant evolutionary biologists, Richard Lewontin has also been a leading critic of those—scientists and non-scientists alike—who would misuse the science to which he has contributed so much. In The Triple Helix, Lewontin the scientist and Lewontin the critic come together to provide a concise, accessible account of what his work has taught him about biology and about its relevance to human affairs. In the process, he exposes some of the common and troubling misconceptions that misdirect and stall our understanding of biology and evolution.

The central message of this book is that we will never fully understand living things if we continue to think of genes, organisms, and environments as separate entities, each with its distinct role to play in the history and operation of organic processes. Here Lewontin shows that an organism is a unique consequence of both genes and environment, of both internal and external features. Rejecting the notion that genes determine the organism, which then adapts to the environment, he explains that organisms, influenced in their development by their circumstances, in turn create, modify, and choose the environment in which they live.

The Triple Helix is vintage Lewontin: brilliant, eloquent, passionate, and deeply critical. But it is neither a manifesto for a radical new methodology nor a brief for a new theory. It is instead a primer on the complexity of biological processes, a reminder to all of us that living things are never as simple as they may seem.

At a time when many people around the world are living into their tenth decade, the longest longitudinal study of human development ever undertaken offers some welcome news for the new old age: our lives continue to evolve in our later years, and often become more fulfilling than before.

Begun in 1938, the Grant Study of Adult Development charted the physical and emotional health of over 200 men, starting with their undergraduate days. The now-classic Adaptation to Life reported on the men’s lives up to age 55 and helped us understand adult maturation. Now George Vaillant follows the men into their nineties, documenting for the first time what it is like to flourish far beyond conventional retirement.

Reporting on all aspects of male life, including relationships, politics and religion, coping strategies, and alcohol use (its abuse being by far the greatest disruptor of health and happiness for the study’s subjects), Triumphs of Experience shares a number of surprising findings. For example, the people who do well in old age did not necessarily do so well in midlife, and vice versa. While the study confirms that recovery from a lousy childhood is possible, memories of a happy childhood are a lifelong source of strength. Marriages bring much more contentment after age 70, and physical aging after 80 is determined less by heredity than by habits formed prior to age 50. The credit for growing old with grace and vitality, it seems, goes more to ourselves than to our stellar genetic makeup.

Talk is of central importance to politics of almost every kind—it’s no accident that when the ancient Greeks first attempted to examine politics systematically, they developed the study of rhetoric. In Tropes of Politics, John Nelson applies rhetorical analysis first to political theory, and then to politics in practice. He offers a full and deep critical examination of political science and political theory as fields of study, and then undertakes a series of creative examinations of political rhetoric, including a deconstruction of deliberation and debate by the U.S. Senate prior to the Gulf War.

Using the neglected arts of argument refined by the rhetoric of inquiry, Nelson traces how everyday words like consent and debate construct politics in much the same way that poets such as Mamet and Shakespeare construct plays, and he shows how we are remaking our politics even as we speak. Tropes of Politics explores how politicians take stands and political scientists probe representation, how experts become informed even as citizens become authorities, how students actually reinvent government while professors merely model politics, how senators wage war yet keep comity among themselves.

The action, Nelson shows, is in the tropes: these figures of speech and images of deed can persuade us to turn from ideologies like liberalism toward spectacles about democracy or movements into environmentalism and feminism. His argument is that inventive attention to tropes can mean better participation in politics. And the argument is in the tropes—evidence itself as sights or citations, governments as machines or men, politics as hardball or softball, deliberations as freedoms or constraints, borders as fringes or friends.

Trophic Cascades is the first comprehensive presentation of the science on this subject. It brings together some of the world’s leading scientists and researchers to explain the importance of large animals in regulating ecosystems, and to relate that scientific knowledge to practical conservation.

Chapters examine trophic cascades across the world’s major biomes, including intertidal habitats, coastal oceans, lakes, nearshore ecosystems, open oceans, tropical forests, boreal and temperate ecosystems, low arctic scrubland, savannas, and islands. Additional chapters consider aboveground/belowground linkages, predation and ecosystem processes, consumer control by megafauna and fire, and alternative states in ecosystems. An introductory chapter offers a concise overview of trophic cascades, while concluding chapters consider theoretical perspectives and comparative issues.

Trophic Cascades provides a scientific basis and justification for the idea that large predators and top-down forcing must be considered in conservation strategies, alongside factors such as habitat preservation and invasive species. It is a groundbreaking work for scientists and managers involved with biodiversity conservation and protection.

While today’s Greenland is largely covered in ice, in the time of the dinosaurs the area was a lushly forested, tropical zone. Tropical Arctic tracks a ten-million-year window of Earth’s history when global temperatures soared and the vegetation of the world responded.

A project over eighteen years in the making, Tropical Arctic is the result of a unique collaboration between two paleobotanists, Jennifer C. McElwain and Ian J. Glasspool, and award-winning scientific illustrator Marlene Hill Donnelly. They began with a simple question: “What was the color of a fossilized leaf?” Tropical Arctic answers that question and more, allowing readers to experience Triassic Greenland through three reconstructed landscapes and an expertly researched catalog of extinct plants. A stunning compilation of paint and pencil art, photos, maps, and engineered fossil models, Tropical Arctic blends art and science to bring a lost world to life. Readers will also enjoy a front-row seat to the scientific adventures of life in the field, with engaging anecdotes about analyzing fossils and learning to ward off polar bear attacks.

Tropical Arctic explains our planet’s story of environmental upheaval, mass extinction, and resilience. By looking at Earth’s past, we see a glimpse of the future of our warming planet—and learn an important lesson for our time of climate change.

Only a day's drive south of the U.S.-Mexico border, a tropical deciduous forest opens up a world of exotic trees and birds that most people associate with tropical forests of more southerly latitudes. Like many such forests around the world, this diverse ecosystem is highly threatened, especially by large-scale agricultural interests that are razing it in order to plant grass for cattle.

This book introduces the tropical deciduous forest of the Alamos region of Sonora, describing its biodiversity and the current threats to its existence. The book's contributors present the most up-to-date scientific knowledge of this threatened ecosystem. They review the natural history and ecology of its flora and fauna and explore how native peoples use the forest's many resources.

Included in the book's coverage is a comprehensive plant list for the Río Cuchujaqui area that well illustrates the diversity of the forest. Other contributions examine tree species used by Mayo Indians and the numerous varieties of domesticated plants that have been developed over the centuries by the Mayos and other indigenous peoples. Also examined are the diversity and distribution of reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and birds in the region.

The Tropical Deciduous Forest of Alamos provides critical information about a globally important biome. It complements other studies of similar forests and allows a better understanding of a diverse but vanishing ecosystem.

Country case studies investigate key factors that influence the economics of tropical deforestation and land use. Articles illustrate how innovative economic models can be used effectively to investigate a range of important influences on tropical land use changes in a variety of representative developing countries. The countries covered are: Brazil, India, Malaysia, Panama, the Philippines, Thailand, and Uganda.

Written by experts in the field of tropical ecology, Tropical Forest Diversity and Dynamism will appeal to students and professionals with an interest in community ecology and patterns of diversity.

Tropical Forest Remnants provides the best information available to help us

understand, manage, and conserve the remaining fragments. Covering geographic areas from Southeast Asia and Australia to Madagascar and the New World, this volume summarizes what is known about the ecology, management, restoration, socioeconomics, and conservation of fragmented forests. Thirty-three papers present results of recent research as

well as updates from decades-long projects in progress. Two final chapters synthesize the state of research on tropical forest fragmentation and identify key priorities for future work.