Cloth: 978-0-674-37301-3

Library of Congress Classification LD2151.H29 1982

Dewey Decimal Classification 378.7444

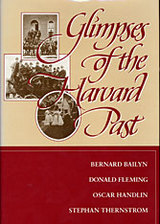

If Harvard can be said to have a literature all its own, then few universities can equal it in scope. Here lies the reason for this anthology—a collection of what Harvard men (teachers, students, graduates) have written about Harvard in the more than three centuries of its history. The emphasis is upon entertainment, upon readability; and the selections have been arranged to show something of the many variations of Harvard life.

For all Harvard men—and that part of the general public which is interested in American college life—here is a rich treasury. In such a Harvard collection one may expect to find the giants of Harvard’s last 75 years—Eliot, Lowell, and Conant—attempting a definition of what Harvard means. But there are many other familiar names—Henry Dunster, Oliver Wendell Holmes, James Russell Lowell, Henry Adams, Charles M. Flandrau, William and Henry James, Owen Wister, Thomas Wolfe, John P. Marquaud. Here is Mistress Eaton’s confession about the bad fish served to the wretched students of Harvard’s early years; here too is President Holyoke’s account of the burning of Harvard Hall; a student’s description of his trip to Portsmouth with that aged and Johnsonian character, Tutor Henry Flynt; Cleveland Amory’s retelling of the murder of Dr. George Parkman; Mayor Quiney’s story of what happened in Cambridge when Andrew Jackson came to get an honorary degree; Alistair Cooke’s commentary on the great Harvard–Yale cricket match of 1951. There are many sorts of Harvard men in this book—popular fellows like Hammersmith, snobs like Bertie and Billy, the sensitive and the lonely like Edwin Arlington Robinson and Thomas Wolfe, and independent thinkers like John Reed. Teachers and pupils, scholars and sports, heroes and rogues pass across the Harvard stage through the struggles and the tragedies to the moments of triumph like the Bicentennial or the visit of Winston Churchill.

And speaking of visits, there are the visitors too—the first impressions of Harvard set down by an assortment of travelers as various as Dickens, Trollope, Rupert Brooke, Harriet Martineau, and Francisco de Miranda, the “precursor of Latin American independence.”

For the Harvard addict this volume is indispensable. For the general reader it is the sort of book that goes with a good living-room fire or the blissful moments of early to bed.

See other books on: Educators | Harvard University | New England (CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT) | Revised Edition | Selections

See other titles from Harvard University Press