Paper: 978-0-8214-2466-7 | Cloth: 978-0-8214-2445-2 | eISBN: 978-0-8214-4737-6

Library of Congress Classification JS7655.3.A3

Dewey Decimal Classification 320.809667

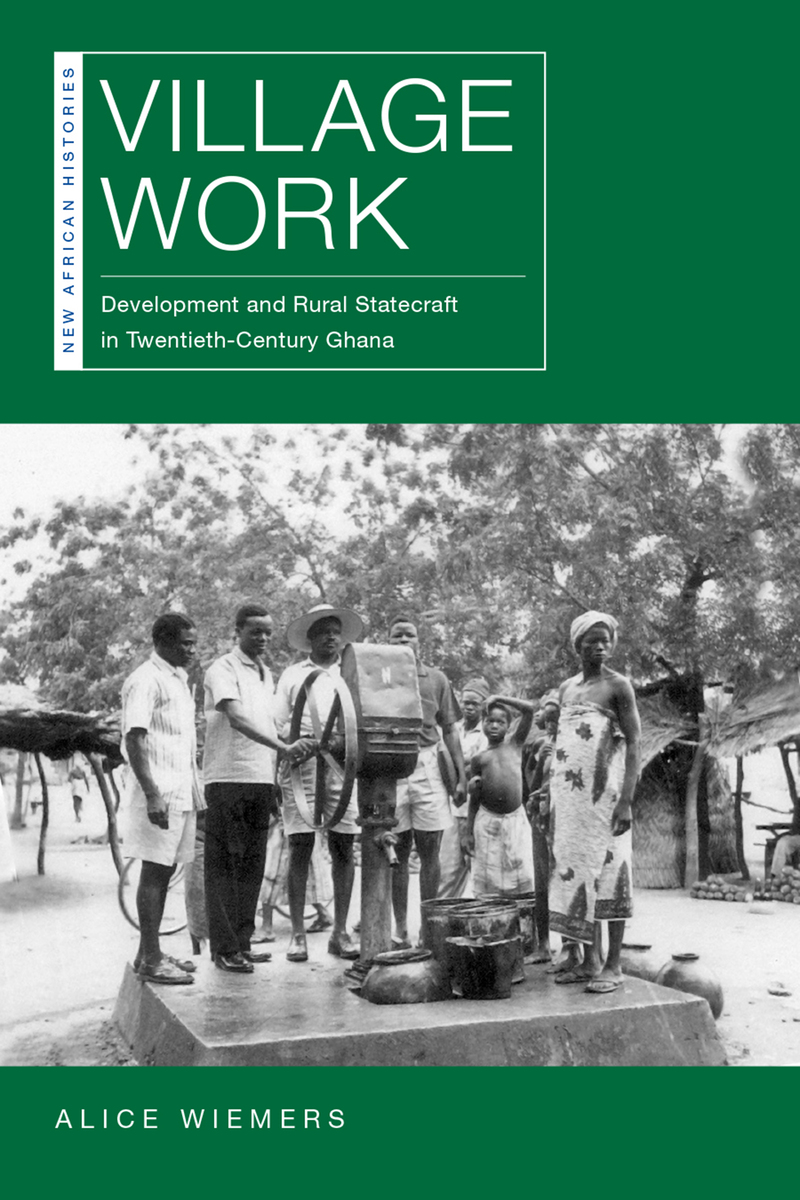

A robust historical case study that demonstrates how village development became central to the rhetoric and practice of statecraft in rural Ghana.

Combining oral histories with decades of archival material, Village Work formulates a sweeping history of twentieth-century statecraft that centers on the daily work of rural people, local officials, and family networks, rather than on the national governments and large-scale plans that often dominate development stories. Wiemers shows that developmentalism was not simply created by governments and imposed on the governed; instead, it was jointly constructed through interactions between them.

The book contributes to the historiographies of development and statecraft in Africa and the Global South by

- emphasizing the piecemeal, contingent, and largely improvised ways both development and the state are comprised and experienced

- providing new entry points into longstanding discussions about developmental power and discourse

- unsettling common ideas about how and by whom states are made

- exposing the importance of unpaid labor in mediating relationships between governments and the governed

- showing how state engagement could both exacerbate and disrupt inequities

Despite massive changes in twentieth-century political structures—the imposition and destruction of colonial rule, nationalist plans for pan-African solidarity and modernization, multiple military coups, and the rise of neoliberal austerity policies—unremunerated labor and demonstrations of local leadership have remained central tools by which rural Ghanaians have interacted with the state. Grounding its analysis of statecraft in decades of daily negotiations over budgets and bureaucracy, the book tells the stories of developers who decided how and where projects would be sited, of constituents who performed labor, and of a chief and his large cadre of educated children who met and shaped demands for local leaders. For a variety of actors, invoking “the village” became a convenient way to allocate or attract limited resources, to highlight or downplay struggles over power, and to forge national and international networks.

See other books on: Central-local government relations | Developing & Emerging Countries | Economic development | Ghana | Local government

See other titles from Ohio University Press