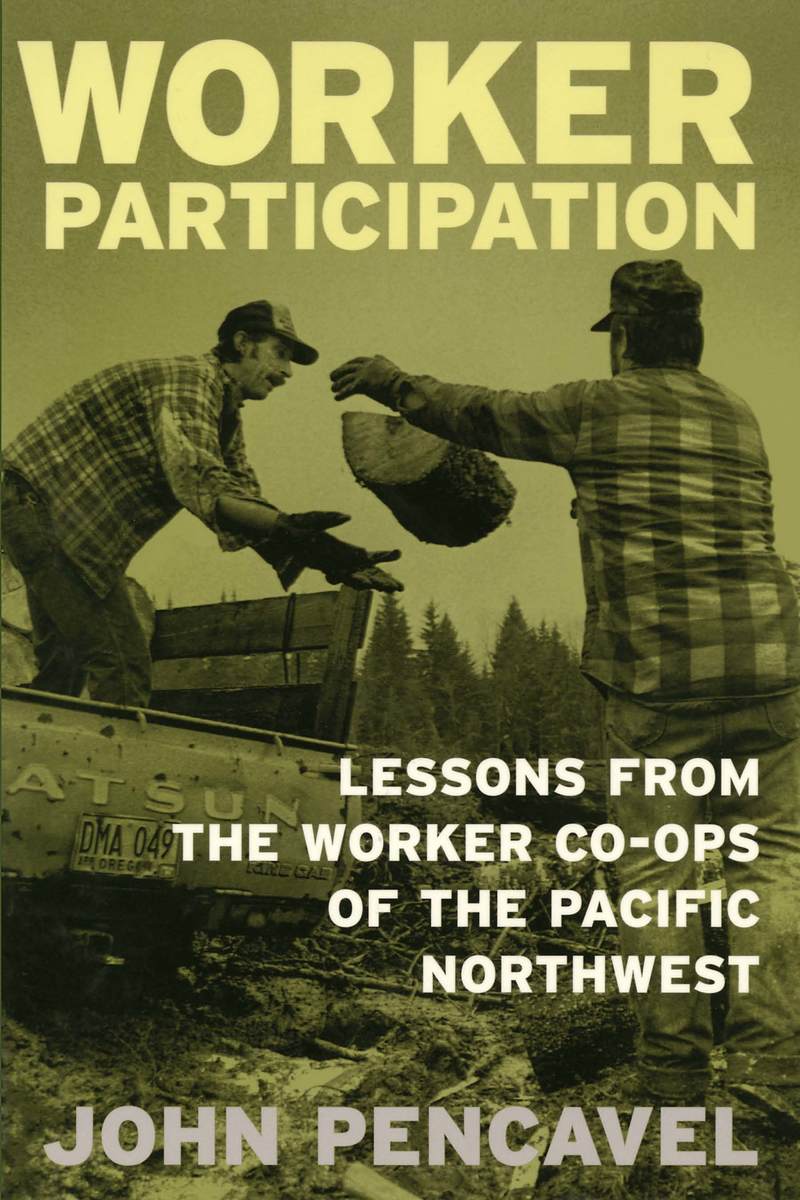

Worker Participation: Lessons from Worker Co-ops of the Pacific Northwest

Russell Sage Foundation, 2001

Paper: 978-0-87154-656-2 | eISBN: 978-1-61044-443-9 | Cloth: 978-0-87154-655-5

Library of Congress Classification HD5660.U52N677 2001

Dewey Decimal Classification 331.0112

Paper: 978-0-87154-656-2 | eISBN: 978-1-61044-443-9 | Cloth: 978-0-87154-655-5

Library of Congress Classification HD5660.U52N677 2001

Dewey Decimal Classification 331.0112

ABOUT THIS BOOK | AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY | TOC

ABOUT THIS BOOK

Once they accept a job, most Americans have little control over their work environments. In Worker Participation, John Pencavel examines some of those rare workplaces where employees both own and manage the companies they work for: the plywood cooperatives and forest worker cooperatives of the Pacific Northwest. Rather than relying on abstract theories, Pencavel reviews the actual experiences of these two groups of worker co-ops. He focuses on how worker-owned companies perform when compared to more traditional firms and whether companies operate more efficiently when workers determine how they are run. He also looks at the long-term viability of these enterprises and why they are so unusual. Most businesses are constantly caught in the battle over whether to use the firm's profits to pay labor or to increase capital. Worker cooperatives provide an appealing case study because the interests of labor and capital are aligned. If individuals have a role in setting goals, they should have an added incentive to help meet those goals, and productivity should benefit. On the other hand, observers have long argued that, since any single employee in a co-op reaps only a small benefit from working hard, workers may shirk work, and productivity can flag. Furthermore, co-ops often have difficulty raising capital, since they are constrained by how much money the workers have, and banks are often reluctant to lend them money. Using some fifteen years of data on forty mills in Washington State, Pencavel examines how worker co-ops really function. He assesses the practical problems of running a workplace where every employee is a boss. He looks at worker productivity, on-the-job injuries and financial risks facing owner-workers. He considers whether co-ops are inherently unstable and if they are plagued by infighting among the many worker-owners. Although many of the co-ops he studied have closed or been replaced by conventional businesses, Pencavel judges them to have been a success. Despite the risks inherent in such operations, allowing workers to make the decisions that profoundly affect them produces many benefits, including workplace efficiency and increased job security. However, Pencavel concludes, if more Americans are to enjoy such a working arrangement, labor laws will have to be changed, participation encouraged, and a more vigorous public debate about worker participation must take place. This book provides an excellent place to start the discussion.

See other books on: Industrial management | Lessons | Northwest, Pacific | Pacific Northwest | Workplace Culture

See other titles from Russell Sage Foundation