eISBN: 978-1-4773-0361-0 | Cloth: 978-1-4773-0359-7 | Paper: 978-1-4773-1221-6

Library of Congress Classification Q127.T9S54 2015

Dewey Decimal Classification 509.560903

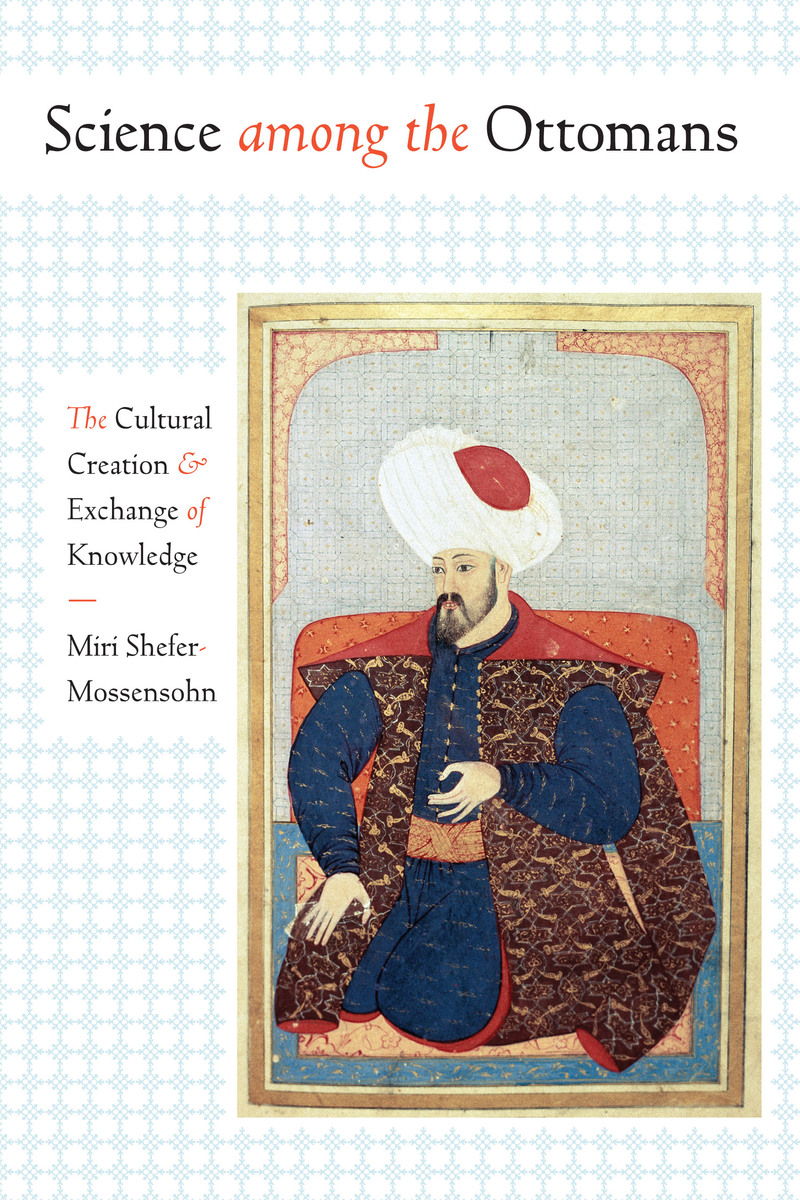

Scholars have long thought that, following the Muslim Golden Age of the medieval era, the Ottoman Empire grew culturally and technologically isolated, losing interest in innovation and placing the empire on a path toward stagnation and decline. Science among the Ottomans challenges this widely accepted Western image of the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Ottomans as backward and impoverished.

In the first book on this topic in English in over sixty years, Miri Shefer-Mossensohn contends that Ottoman society and culture created a fertile environment that fostered diverse scientific activity. She demonstrates that the Ottomans excelled in adapting the inventions of others to their own needs and improving them. For example, in 1877, the Ottoman Empire boasted the seventh-longest electric telegraph system in the world; indeed, the Ottomans were among the era’s most advanced nations with regard to modern communication infrastructure. To substantiate her claims about science in the empire, Shefer-Mossensohn studies patterns of learning; state involvement in technological activities; and Turkish- and Arabic-speaking Ottomans who produced, consumed, and altered scientific practices. The results reveal Ottoman participation in science to have been a dynamic force that helped sustain the six-hundred-year empire.

See other books on: Exchange | Ottoman Empire, 1288-1918 | Science and state | Turkey | Turkey & Ottoman Empire

See other titles from University of Texas Press