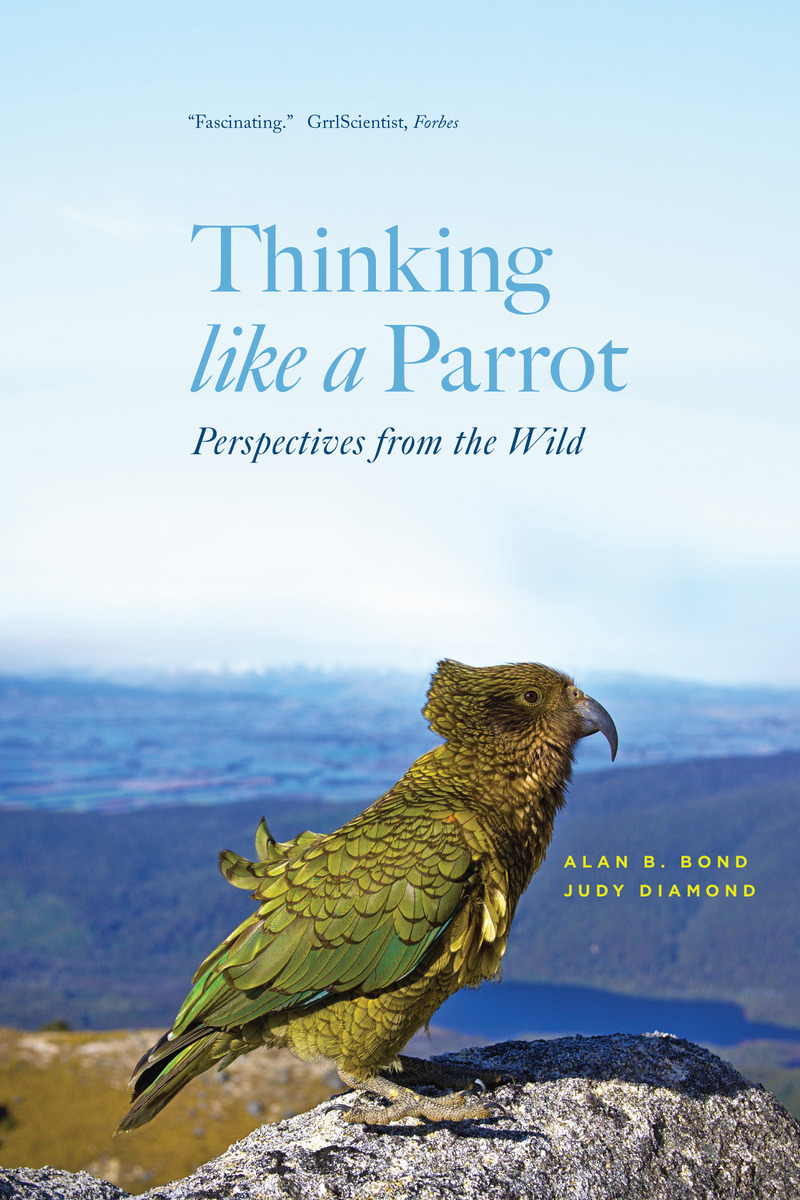

Thinking like a Parrot

Perspectives from the Wild

University of Chicago Press, 2019

Cloth: 978-0-226-24878-3 | Paper: 978-0-226-81520-6 | Electronic: 978-0-226-24881-3

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226248813.001.0001

Cloth: 978-0-226-24878-3 | Paper: 978-0-226-81520-6 | Electronic: 978-0-226-24881-3

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226248813.001.0001

ABOUT THIS BOOKAUTHOR BIOGRAPHYREVIEWSTABLE OF CONTENTS

ABOUT THIS BOOK

From two experts on wild parrot cognition, a close look at the intelligence, social behavior, and conservation of these widely threatened birds.

People form enduring emotional bonds with other animal species, such as dogs, cats, and horses. For the most part, these are domesticated animals, with one notable exception: many people form close and supportive relationships with parrots, even though these amusing and curious birds remain thoroughly wild creatures. What enables this unique group of animals to form social bonds with people, and what does this mean for their survival?

In Thinking like a Parrot, Alan B. Bond and Judy Diamond look beyond much of the standard work on captive parrots to the mischievous, inquisitive, and astonishingly vocal parrots of the wild. Focusing on the psychology and ecology of wild parrots, Bond and Diamond document their distinctive social behavior, sophisticated cognition, and extraordinary vocal abilities. Also included are short vignettes—field notes on the natural history and behavior of both rare and widely distributed species, from the neotropical crimson-fronted parakeet to New Zealand’s flightless, ground-dwelling kākāpō. This composite approach makes clear that the behavior of captive parrots is grounded in the birds’ wild ecology and evolution, revealing that parrots’ ability to bond with people is an evolutionary accident, a by-product of the intense sociality and flexible behavior that characterize their lives.

Despite their adaptability and intelligence, however, nearly all large parrot species are rare, threatened, or endangered. To successfully manage and restore these wild populations, Bond and Diamond argue, we must develop a fuller understanding of their biology and the complex set of ecological and behavioral traits that has led to their vulnerability. Spanning the global distribution of parrot species, Thinking like a Parrot is rich with surprising insights into parrot intelligence, flexibility, and—even in the face of threats—resilience.

People form enduring emotional bonds with other animal species, such as dogs, cats, and horses. For the most part, these are domesticated animals, with one notable exception: many people form close and supportive relationships with parrots, even though these amusing and curious birds remain thoroughly wild creatures. What enables this unique group of animals to form social bonds with people, and what does this mean for their survival?

In Thinking like a Parrot, Alan B. Bond and Judy Diamond look beyond much of the standard work on captive parrots to the mischievous, inquisitive, and astonishingly vocal parrots of the wild. Focusing on the psychology and ecology of wild parrots, Bond and Diamond document their distinctive social behavior, sophisticated cognition, and extraordinary vocal abilities. Also included are short vignettes—field notes on the natural history and behavior of both rare and widely distributed species, from the neotropical crimson-fronted parakeet to New Zealand’s flightless, ground-dwelling kākāpō. This composite approach makes clear that the behavior of captive parrots is grounded in the birds’ wild ecology and evolution, revealing that parrots’ ability to bond with people is an evolutionary accident, a by-product of the intense sociality and flexible behavior that characterize their lives.

Despite their adaptability and intelligence, however, nearly all large parrot species are rare, threatened, or endangered. To successfully manage and restore these wild populations, Bond and Diamond argue, we must develop a fuller understanding of their biology and the complex set of ecological and behavioral traits that has led to their vulnerability. Spanning the global distribution of parrot species, Thinking like a Parrot is rich with surprising insights into parrot intelligence, flexibility, and—even in the face of threats—resilience.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

Alan B. Bond is professor emeritus of biological sciences at the University of Nebraska and Judy Diamond is professor and curator at the University of Nebraska State Museum. Together they have studied the social behavior, cognition, and vocalizations of wild parrots for more than three decades. They are coauthors of Kea, Bird of Paradox: The Evolution and Behavior of a New Zealand Parrot and Concealing Coloration in Animals. For more on their research, please visit the website of the Center for Avian Cognition, http://www.aviancog.org/.

REVIEWS

“There is indeed something special about parrots. Bond and Diamond have captured beautifully the essence of both the extreme complexity and sophistication of the wild birds and our complex relationship with them. Thinking like a Parrot nails the most difficult aspect by managing to explain, without getting bogged down, the high levels of cognition and intelligence of parrots, especially in context of their complex social lives. Totally original and engagingly written.”

— Robert Heinsohn, Australian National University, coeditor of "Boom and Bust: Bird Stories for a Dry Country"“Although parrots have shared our hearts and hearths for hundreds of years, our understanding of their natural behavior has remained shrouded in mystery—until now. As parrots are notoriously difficult to study in the wild, the soap opera of their existence has remained unclear. In Thinking like a Parrot, Bond and Diamond have looked behind the curtain to reveal that parrots possess minds and behavior as complex and intriguing as any creatures in the animal kingdom. This is an exceptional guide for anyone who wants to discover more about how this stunning group of birds think about the world. As we continue to destroy the diverse habitats that wild parrots call home, it’s become apparent that we need to learn all we can about them before it’s too late. Parrots are so much more than the chatty, funny trickster companions that we know and love. This is the perfect guide to learning their secrets.”

— Nathan J. Emery, Queen Mary University of London,author of "Bird Brain: An Exploration of Avian Intelligence"“Parrots have unusually large brains, surprisingly flexible learning and intelligence, amazing mimetic abilities, and rich, complicated social interactions. What evolutionary pressures have shaped these traits? In this entertaining and well-written book, Bond and Diamond offer a vivid portrait of the lives of parrots, keas, and macaws. It is a scientifically up-to-date tour de force, easily accessible to scientists and non-scientists alike, that elegantly summarizes the birds’ history, biology, and spread throughout the world—not to mention their complex relations with humans, who have for centuries selectively bred them for their wits and personalities.”

— Robert M. Seyfarth, University of Pennsylvania, coauthor of "The Social Origins of Language" and "Baboon Metaphysics: The Evolution of a Social Mind"“The minds of wild parrots brim with intelligence, and their lives with clever, flexible, and exuberant behavior. This fascinating book takes us into their universe to discover not just how these birds live, but how they think, ‘talk,’ and feel. You’ll be amazed by the surprises—the slang of kākās, the playful gangs of galahs, the ingenious adaptability of rose-ringed parakeets.”

— Jennifer Ackerman, author of "The Genius of Birds""There have been numerous books written about these remarkably brainy but especially endangered birds. This is one of the very best. The authors have studied the lives of wild parrots for over thirty years. Their groundbreaking research into the social behavior, ecology, and intelligence of a wide range of parrot species greatly augments the knowledge obtained from studies of captive birds, and plays an important part in helping conservationists understand how best to save them. This is both a beautifully written survey that anyone can appreciate and a serious reference work."

— BBC Wildlife"This fascinating and meticulously researched book explores the astonishing levels of cognition and intelligence of wild parrots, especially in the context of their complex social lives. . . . Under [Bond and Diamond's] expert guidance, we meet brilliant keas, cheeky sulphur-crested cockatoos, affable crimson-fronted parakeets, dazzling rainbow lorikeets, adaptable rose-ringed parakeets, and adorable kakapos. . . . This book is filled with intriguing information, some of it new or unfamiliar to those who know parrots best. . . . Engaging and wonderfully-written. . . . Over the years, I have read almost every book about parrots published in the English language, and this is, hands down, the best parrot book published in the past ten years, and certainly one of the best ever published. This succinct and erudite summary of the latest scientific research into these birds’ natural history, biology, ecology, and evolution is most unusual because it will be read and cherished by ornithologists and scientists as well as non-specialists, and by parrot breeders, behaviorists, and owners alike for years to come, and will appeal to anyone who wishes to learn more about how parrots view the world."

— GrrlScientist, Forbes"Parrots are birds that are familiar to all, famed for their beauty, their ability to mimic and talk, and for their emotional bonds with humans. Most books about parrots are either field guides to all the species or books on captive care. Here ecologists Bond and Diamond focus instead on the minds and behavior of parrots in the wild, drawing together years of their own field work and that of scores of other researchers; the massive bibliography alone is worth the price of the book. Divided into six sections, this inquiry into wild parrots examines their evolution, their behavior, their sociability, their cognition, the lives of the few parrot species that have expanded their ranges, and, finally, the conservation of parrots, the majority of which are threatened by human-caused environmental change. Throughout, Bond and Diamond intersperse tales of their own research on New Zealand’s parrots with studies of other parrot species around the world, illuminating the adaptability and intelligence of these gorgeous birds even in the face of environmental stress. Parrots are very sophisticated animals! . . . Give this very readable compendium to bird-loving and nature-intrigued teens."

— Booklist"Under the 'thinking' rubric are chapters on the evolution of brain and sensory systems; various models of behavior, social relationships and communication, adaptive flexibility or lack (hence range expansions and contractions); and something called 'intelligence.' Parrots have it and outperform corvids (crows, jays, ravens), the next 'smartest' bird group. Anyone who has cohabited with parrots (they are more companions than pets) knows about their 'smarts,' dealing with novelties, persistence, and long-term memory. This book focuses on lessons from wild parrots: from both authors’ studies of parrots on several continents and from the literature. This is a far-ranging work, clearly written and extensively referenced and generally makes interesting reading. Even an experienced parrot biologist will say, 'I didn’t know they could do that.'"

— Choice"Thinking like a Parrot describes the behavior, cognition, ecology, and conservation of wild parrots and includes a number of appendixes, an extensive list of references, and a beautiful set of color plates. The book does not discuss parrots as though they were small humans but, instead, is a well-considered attempt to explain parrot behavior in terms of parrot ecology and evolution. . . . I highly recommend Thinking like a Parrot to anyone interested in birds, animal cognition, and conservation and management."

— BioScience"Bond and Diamond take on the immense task of elucidating aspects of parrot evolution, ecology, and behavior that have largely remained inaccessible, endeavoring to fill a gaping niche of priceless information and insight about these charismatic organisms. A collection of informative essays preceded by vivid vignettes of recollected experiences with wild parrots, Thinking like a Parrot takes its readers down a logical path of immersion into the reality that parrots face. . . . Bond and Diamond have taken on a very ambitious task in Thinking like a Parrot, shouldering the heavy responsibility of bringing so many commonly unknown aspects of parrots to light and in charming detail. The book is a fabulous read, with excellent starting points to enable readers to delve deeper into topics concerning the lives of wild parrots. Even as bird experts, we discovered many fascinating new details. It is a welcome, necessary, and appreciated body of work; even long-time parrot owners and enthusiasts would be well served to read this book."

— Current Biology