8 have author last names that start with L have author last names that start with L

This is the first-ever French-English edition of La Rochefoucauld’s Réflexions, ou sentences et maximes morales, long known in English simply as the Maxims. The translation, the first to appear in forty years, is completely new and aims – unlike all previous versions – at being as literal as possible. This involves, among other things, rendering the same word – for example, amour-propre as “self-love” – as consistently throughout as good sense allows. This also means that the translators have made every effort to maintain La Rochefoucauld’s word order. This allows the reader the best vantage point for viewing La Rochefoucauld’s dramatic and paradoxical juxtapositions of words and ideas, juxtapositions of the utmost importance to understanding his thought. Despite the translation’s concern with literalness, careful attention has been paid to the nuances of the literary character of the Maxims. In addition, this work contains a series of detailed indices that will greatly aid the reader in finding just the right maxim, and an updated version, in English, of the original French index of the work.

At the heart of La Rochefoucauld’s Maxims lies the attempt to disclose the great disparity between the exaggerated self-estimation of men and women and their actual condition. As La Rochefoucauld (1613–1680) unremittingly unmasks various pretenses, heelaborately exposes the complexity of motives which underlie and inform human conduct: whereas many endeavor to reveal a unity in plurality, La Rochefoucauld endeavors to reveal a plurality in unity. Playful, yet serious, humorous, ironic yet direct, poetic yet philosophical, the Maxims penetrate to themes at the center of reflection and judgment about the human situation. Worthy of study at any time, the Maxims are especially relevant in the strange times in which we live.

This edition includes the 504 maxims of the definitive, fifth edition of 1678, along with 137 other maxims which were either withdrawn from earlier editions or published posthumously. In addition to the maxims, La Rochefoucauld’s self-portrait and Cardinal de Retz’s portrait of La Rochefoucauld are also included.

The writings of Pope Pius VI, head of the Catholic Church during the most destructive period of the French Revolution, were compiled in two volumes by M.N.S. Guillon and published in 1798 and 1800. But during the Revolution, the reign of Napoleon, and the various revolutionary movements of the 19th century, there were extraordinary efforts to destroy writings that critiqued the revolutionary ideology. Many books and treatises, if they survived the revolution or the sacking from Napoleon’s armies. To this day, no public copy of Guillon’s work exists in Paris.

Now, for the first time in English, these works comprising the letters, briefs, and other writings of Pius VI on the French Revolution are available. Volume I treats the first shock of the Revolution and the efforts of the Pope in 1790 and 1791 to oppose the Civil Constitution of the Clergy (which famous revolutionary and shrewd diplomat Talleyrand referred to as “the greatest fault of the National Assembly”). Volume II will be published later, and deals with the aftermath of the Civil Constitution through Pius’s death in exile). Editor and translator Jeffrey Langan presents the materials leading up to and directly connected with these decrees, in which the National Assembly attempted to set up a Catholic Church that would be completely submissive to the demands of the Assembly. Volume I also covers Pius’s efforts to deal with the immediate aftermath of the Constitution after the National Assembly implemented it, including his encyclical, Quod Aliquantum.

The letters will show how Pius chose to oppose the Civil Constitution. He did so not by a public campaign, for he had no real temporal power to oppose the violence, but by attempting to work personally with Louis XVI and various archbishops in France to articulate what were the points on which he could concede (matters dealing with the political structures of France) and what were the essential points in which he could not concede (matters dealing with the organization of dioceses and appointment of bishops).

Since the 1980s, with the writings and school that developed around François Furet, as well as Simon Schama’s Citizens, a new debate over the French Revolution has ensued, bringing forth a more objective account of the Revolution, one that avoids an excessively Marxist lens and that brings to light some of its defects and more gruesome parts – the destruction and theft of Church property, and the sadistic methods of torture and killing of priests, nuns, aristocrats, and fellow-revolutionaries.

An examination of the writings of Pius VI will not only help set the historical record straight for English-speaking students of the Revolution, it will also aid them to better understand the principles that the Catholic Church employs when confronted with chaotic political change. They will see that the Church has a principled approach to distinguishing, while not separating, the power of the Church and the power of the state. They will also see, as Talleyrand himself also saw, that one of the essential elements that makes the Church the Church is the right to appoint bishops and to discipline its own bishops. The Church herself recognizes that she cannot long survive without this principle that guarantees her unity.

Pius VI’s efforts were able to keep the Catholic Church intact (though badly bruised) so that she could reconstitute herself and build up a vibrant life in 19th-century France. (He did this in the face of the Church’s prestige having sunk to historic lows; some elites in Europe thought there would be no successor to Pius and jokingly referred to him as “Pius the Last.”) He began a process that led to the restoration of the prestige of the Papacy throughout the world, and he initiated a two-century process that led to the Church finally being able to select bishops without any interference from secular authorities. This had been at least a 1,000-year problem in the history of the Church. By 1990, only two countries of the world, China and Vietnam, were interfering in any significant way in the process that the Church used to select bishops.

Pius VI’s papacy, especially during the years of the French Revolution, was a pivotal point for the French Revolution and for the interaction between Church and state in Western history. All freedom-loving people will be happy to read his distinc-tions between the secular power and the spiritual power. His papacy also was important for the internal developments that the Church would make over the next 200 years with respect to its self-understanding of the Papacy and the role of the bishop.

Entrée G. K. Chesterton. If Girard recognizes the talent certain literary figures have for observing what celebrated philosophers fail to see, Chesterton is one of these men of real vision. Lefler in his match-making is interested in “Romance and the romantic,” and placing Girard and Chesterton in a kind of dialogue he draws a clearer concept of Romanticism. Who is the Romatic hero? And why do we so badly need to know? If what Lefler sees in Chesterton and Girard requires “special pleading” on the part of the reader for the author to make himself more clear, Lefler obliges. He takes a sharp turn into the Father Brown stories and points the reader to Chesterton’s famous villain: Flambeau, the “colossus of crime”. The moral transition from sinner to saint in Flambeau is strikingly anti-Romantic and, with Girard in mind, also very much anti-mimetic. Or is it? Lefler argues that even Girard would have “inclined his own regal forehead in delight and awe” at Chesterton’s portrayal of the crowning Romantic quality and unlikely machete in an overgrown jungle of the self-intoxicated modern imagination––namely, humility.

Lefler makes his mark in several places with this new study. As literary critic, both Chesterton and Girard are honored. As philosopher, Lefler speaks as if somehow he managed to find a pocket of unpolluted air to breath. As theologian, he betrays that he also loves what Chesterton and Girard loved. And as special service to the reader, the full text of Chesterton’s The Queer Feet is provided.

This new series of scholarly reflections on the interpretation of Socratic philosophy is an inviting combination of intuition and meticulous analysis. Ryszard Legutko provides the reader a monumental service in his confrontation of the most important and influential literature written on the subject to date. He likewise opens the conversation to European contributions and renders Socrates truly a figurehead of future philosophy far beyond being a pillar in ancient thought.

Legutko argues that Socrates was systematic, and his moral views were ultimately grounded in his theory of knowledge that was composed of logically connected propositions (logoi). Reading Plato, Legutko's intuition that Socrates was quite the opposite of the quirky, ironic, and enigmatic character is supported by his demonstration of Socrates' consistency, unity, and hierarchy of thought. He extends Socrates' coherency to a criticism of the democratic mind, framing him even less as a random spit-fire and more the grounded observer. Socrates, argues Letgutko, is well aware of the importance of general concepts and he intended to free these concepts from democratic distortions and give them firm and independent foundations.

In short, 'the way of the gadfly' is a beautiful and precise exploration of order that seeks to be changed by the awareness of this order, and how to wield concepts apart from the motives of arrogance and chaos––neither of which represent nature, and therefore are foreign to the way of the gadfly.

This is a personal and insightful portrait of Pope Pius XII, the memories of Sister M. Pascalina Lehnert, who served as his housekeeper for forty years. Her book, most of it written just a few months after the Pope’s death, shares insights into the person, the life, and the thinking of Pius XII, from his time as Nuncio in Munich until his death. Much of Sister’s motivation in writing this work was to correct the many distortions of fact and interpretation regarding this great pope.

This book was a best seller in the original German, as well as in the Italian and French translations. This is the first edition in English.

These reminiscences were written down at the instructions of Sister’s Superior General, but were not made known to the public until 1982, when it was published in German at the express wishes of Pope John Paul II to publish the work without any changes. So the work remained a lively, flowing account of memories and anecdotes in a simple, spontaneous style. It is a powerful and insightful account of Pius’s daily life, his treatment of those around him, and his concern for the upholding of the traditional teaching of the Church in the face of his awesome burden to lead the Church during World War II.

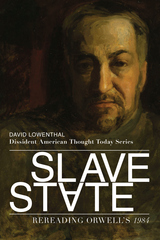

There is no positive political message in 1984, argues Lowenthal, but there is positive moral message that is nearly always overlooked by commentators. “Through the movement of the novel, Orwell tries to impress on the passions, hearts and minds of his readers the most valuable lessons concerning the right and wrong way to live. With the decline of Christianity’s influence in forming the moral sense of the West and the concomitant increase in power hunger, wielding instruments born of modern enlightenment, what mankind most needed was moral guidance, conveyed not abstractly, through philosophy, but in such a way as to grip the whole soul.”

But can Orwell be trusted as a guide to the goodness in human nature? Lowenthal says he can be, and more. He gives us a sketch of the intellectual process that compels Orwell to ultimately outgrow Marxism, his detection and rejection of totalitarian regimes (above all in Communism), and in what way the principles of liberalism of his day were given warning labels by a writer who was not a formally educated political philosopher. Laced with relativism, any current of thought that does not acknowledge the proper ends of man will be effaced by the next master of the masses. Lowenthal echoes Orwell when he says, “we have abandoned inculcating good citizenship, higher ideals and a sense of personal worth in the schools, encouraging instead an aimless low-level conformist ‘individuality’ just waiting to be harnessed together and directed. Given these conditions, can we be sure we have left the conditions to the horrors of 1984 far behind as mere fiction?”

Orwell and Lowenthal are unlikely co-collaborators, unless one perceives how much alike in their exhortations to fellow man they are. The steady tenor of their hard warning is made possible by a hope-soaked confidence that, in utter sobriety, is repulsed by anything that threatens human freedom and dignity. This book is required reading for anyone who believes in the return of socialism. Indeed, any recent university graduate should be debriefed by Lowenthal before entering the real world.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2024

The University of Chicago Press