Honorable Mention, 2020 CALACS Book Prize

Beyond Repair? explores Mayan women’s agency in the search for redress for harm suffered during the genocidal violence perpetrated by the Guatemalan state in the early 1980s at the height of the thirty-six-year armed conflict. The book draws on eight years of feminist participatory action research conducted with fifty-four Q’eqchi’, Kaqchikel, Chuj, and Mam women who are seeking truth, justice, and reparation for the violence they experienced during the war, and the women’s rights activists, lawyers, psychologists, Mayan rights activists, and researchers who have accompanied them as intermediaries for over a decade. Alison Crosby and M. Brinton Lykes use the concept of “protagonism” to deconstruct dominant psychological discursive constructions of women as “victims,” “survivors,” “selves,” “individuals,” and/or “subjects.” They argue that at different moments Mayan women have been actively engaged as protagonists in constructivist and discursive performances through which they have narrated new, mobile meanings of “Mayan woman,” repositioning themselves at the interstices of multiple communities and in their pursuit of redress for harm suffered.

Yielding pivotal new perspectives on the indigenous women of Mexico, Dissident Women: Gender and Cultural Politics in Chiapas presents a diverse collection of voices exploring the human rights and gender issues that gained international attention after the first public appearance of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) in 1994.

Drawing from studies on topics ranging from the daily life of Zapatista women to the effect of transnational indigenous women in tipping geopolitical scales, the contributors explore both the personal and global implications of indigenous women's activism. The Zapatista movement and the Women's Revolutionary Law, a charter that came to have tremendous symbolic importance for thousands of indigenous women, created the potential for renegotiating gender roles in Zapatista communities. Drawing on the original research of scholars with long-term field experience in a range of Mayan communities in Chiapas and featuring several key documents written by indigenous women articulating their vision, Dissident Women brings fresh insight to the revolutionary crossroads at which Chiapas stands—and to the worldwide implications of this economic and political microcosm.

Gender was a fluid potential, not a fixed category, before the Spaniards came to Mesoamerica. Childhood training and ritual shaped, but did not set, adult gender, which could encompass third genders and alternative sexualities as well as "male" and "female." At the height of the Classic period, Maya rulers presented themselves as embodying the entire range of gender possibilities, from male through female, by wearing blended costumes and playing male and female roles in state ceremonies.

This landmark book offers the first comprehensive description and analysis of gender and power relations in prehispanic Mesoamerica from the Formative Period Olmec world (ca. 1500-500 BC) through the Postclassic Maya and Aztec societies of the sixteenth century AD. Using approaches from contemporary gender theory, Rosemary Joyce explores how Mesoamericans created human images to represent idealized notions of what it meant to be male and female and to depict proper gender roles. She then juxtaposes these images with archaeological evidence from burials, house sites, and body ornaments, which reveals that real gender roles were more fluid and variable than the stereotyped images suggest.

Marriage among the Maya of Central America is a model of complementarity between a man and a woman. This union demands mutual respect and mutual service. Yet some husbands beat their wives.

In this pioneering book, Laura McClusky examines the lives of several Mopan Maya women in Belize. Using engaging ethnographic narratives and a highly accessible analysis of the lives that have unfolded before her, McClusky explores Mayan women's strategies for enduring, escaping, and avoiding abuse. Factors such as gender, age inequalities, marriage patterns, family structure, educational opportunities, and economic development all play a role in either preventing or contributing to domestic violence in the village. McClusky argues that using narrative ethnography, instead of cold statistics or dehumanized theoretical models, helps to keep the focus on people, "rehumanizing" our understanding of violence. This highly accessible book brings to the social sciences new ways of thinking about, representing, and studying abuse, marriage, death, gender roles, and violence.

This study of the Guatemalan legal system during the regimes of two of Latin America’s most repressive dictators reveals the surprising extent to which Maya women used the courts to air their grievances and defend their human rights.

Winner, Bryce Wood Book Award, Latin American Studies Association, 2015

Given Guatemala’s record of human rights abuses, its legal system has often been portrayed as illegitimate and anemic. I Ask for Justice challenges that perception by demonstrating that even though the legal system was not always just, rural Guatemalans considered it a legitimate arbiter of their grievances and an important tool for advancing their agendas. As both a mirror and an instrument of the state, the judicial system simultaneously illuminates the limits of state rule and the state’s ability to co-opt Guatemalans by hearing their voices in court.

Against the backdrop of two of Latin America’s most oppressive regimes—the dictatorships of Manuel Estrada Cabrera (1898–1920) and General Jorge Ubico (1931–1944)—David Carey Jr. explores the ways in which indigenous people, women, and the poor used Guatemala’s legal system to manipulate the boundaries between legality and criminality. Using court records that are surprisingly rich in Maya women’s voices, he analyzes how bootleggers, cross-dressers, and other litigants crafted their narratives to defend their human rights. Revealing how nuances of power, gender, ethnicity, class, and morality were constructed and contested, this history of crime and criminality demonstrates how Maya men and women attempted to improve their socioeconomic positions and to press for their rights with strategies that ranged from the pursuit of illicit activities to the deployment of the legal system.

Examines the role of digital technologies in the lives of Kaqchikel Maya women whose husbands work abroad.

Anthropologist Meghan Farley Webb’s ethnography, Public Loves, Private Troubles, uses the lens of cellphones and other digital technologies to unpack marriage, love, sexuality, and family issues of Kaqchikel Maya women who remain in Guatemala while their husbands are part of the transnational migration workforce. Indigenous intimacy has been underexplored in ethnographic literature, and this is among the first books to focus on information technology's impact on intimacy and family in the Maya area. Overall, Webb shows how Maya women are empowered with their more autonomous lives when the husbands are absent but also are constrained by social media monitoring of their activities.

To begin, Webb surveys the Tecpán highland setting and civil war and migration history. She discusses how neoliberal policies are manifested in the financial and emotional stress of having to leave for the United States for economic opportunities. Chapter 1 characterizes the lives of Maya women in Guatemala who “endure” while their husbands are working abroad. Webb describes how marriage, family, and even the Catholic Church shape how the women see themselves and their situations. Chapter 2 delves into the history and use of technologies, such as cellphones and WhatsApp, and how they affect communication in these transnational households. Insight is given to the family and personhood. Chapter 3 focuses on the prominent use of the Facebook platform. Men use the app to conduct extramarital affairs, but the app is also used by couples as a way to express a public performance of devotion and a happy family. Chapter 4 focuses on the surveillance, including malicious gossip, that Kaqchikel women are subjected to especially from their mothers-in-law, who live nearby or in the same household. The narrative culminates in a discussion of how many wives are happier and more empowered without the men at home, yet they still can experience uncertainty, loneliness, and depression.

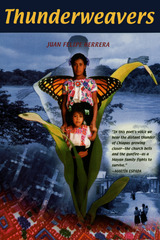

In the winter of 1997, paramilitary agents ambushed and killed many Mayan villagers in Acteal, Chiapas. Gifted writer Juan Felipe Herrera has composed a stirring poem sequence—published in a bilingual format—written in response and homage to those who died, as well as to all those who call for peace and justice in the Mexican highlands and throughout the Americas.

The sections are written in the voices of four women from a family in Chiapas: Xunka, a lost twelve-year-old girl; Pascuala, the mother; grandmother Maruch; and Makal, an older daughter who is pregnant. Each voice weaves into the others and speaks for still other members of the larger Mayan and Native American family.

Thunderweavers is a story of violent displacements in the lives of the most impoverished residents of southern Mexico.Through these words, readers will learn the meaning of transcendence and continuity in the midst of chaos, suffering, and war.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press