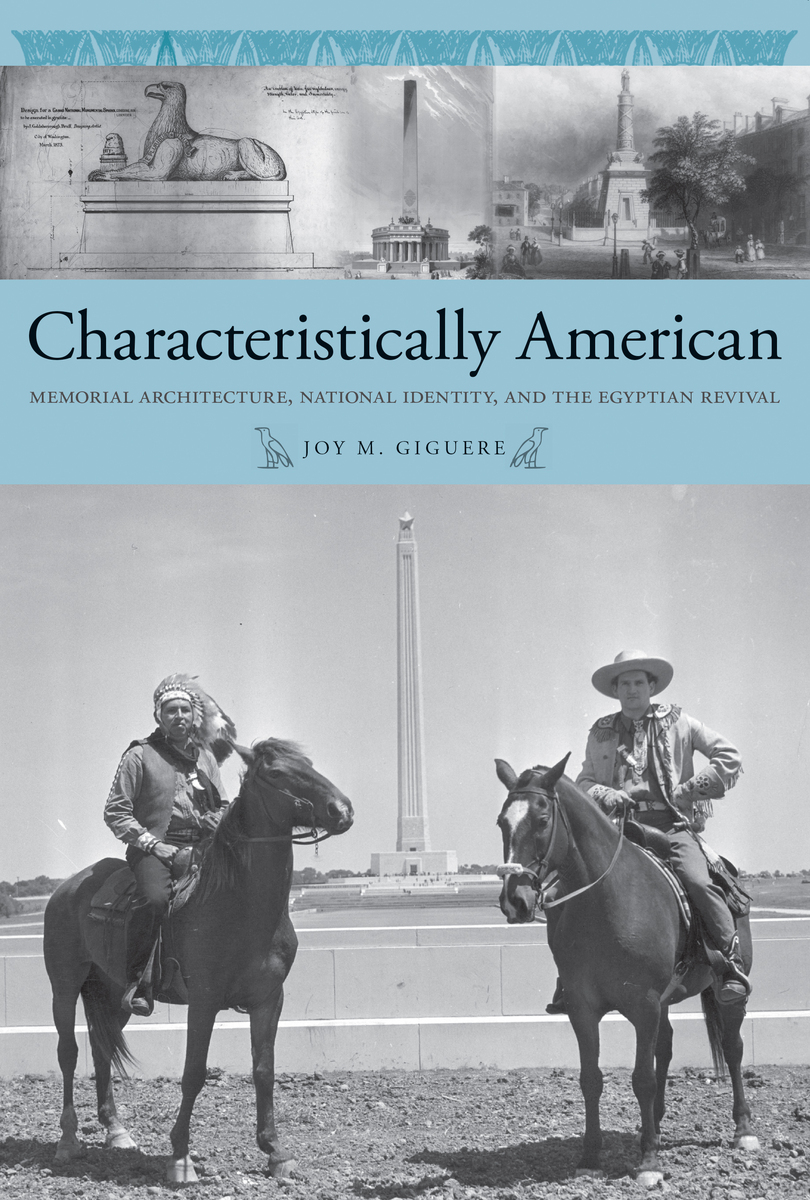

Characteristically American: Memorial Architecture, National Identity, and the Egyptian Revival

University of Tennessee Press, 2014

Cloth: 978-1-62190-039-9 | eISBN: 978-1-62190-077-1 | Paper: 978-1-62190-818-0

Library of Congress Classification NA9347.G54 2014

Dewey Decimal Classification 725.940973

Cloth: 978-1-62190-039-9 | eISBN: 978-1-62190-077-1 | Paper: 978-1-62190-818-0

Library of Congress Classification NA9347.G54 2014

Dewey Decimal Classification 725.940973

ABOUT THIS BOOK | AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY | REVIEWS | TOC | REQUEST ACCESSIBLE FILE

ABOUT THIS BOOK

Prior to the nineteenth century, few Americans knew anything more of Egyptian culture

than what could be gained from studying the biblical Exodus. Napoleon’s invasion of

Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century, however, initiated a cultural breakthrough for

Americans as representations of Egyptian culture flooded western museums and publications,

sparking a growing interest in all things Egyptian that was coined Egyptomania.

As Egyptomania swept over the West, a relatively young America began assimilating

Egyptian culture into its own national identity, creating a hybrid national heritage that

would vastly affect the memorial landscape of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Far more than a study of Egyptian revivalism, this book examines the Egyptian style

of commemoration from the rural cemetery to national obelisks to the Sphinx at Mount

Auburn Cemetery. Giguere argues that Americans adopted Egyptian forms of commemoration

as readily as other neoclassical styles such as Greek revivalism, noting that the

American landscape is littered with monuments that define the Egyptian style’s importance

to American national identity. Of particular interest is perhaps America’s greatest

commemorative obelisk: the Washington Monument. Standing at 555 feet high and

constructed entirely of stone—making it the tallest obelisk in the world—the Washington

Monument represents the pinnacle of Egyptian architecture’s influence on America’s desire

to memorialize its national heroes by employing monumental forms associated with

solidity and timelessness. Construction on the monument began in 1848, but controversy

over its design, which at one point included a Greek colonnade surrounding the obelisk,

and the American Civil War halted construction until 1877. Interestingly, Americans saw

the completion of the Washington Monument after the Civil War as a mending of the

nation itself, melding Egyptian commemoration with the reconstruction of America.

As the twentieth century saw the rise of additional commemorative obelisks, the Egyptian

Revival became ensconced in American national identity. Egyptian-style architecture

has been used as a form of commemoration in memorials for World War I and II, the civil

rights movement, and even as recently as the 9/11 remembrances. Giguere places the Egyptian

style in a historical context that demonstrates how Americans actively sought to forge

a national identity reminiscent of Egyptian culture that has endured to the present day.

than what could be gained from studying the biblical Exodus. Napoleon’s invasion of

Egypt at the end of the eighteenth century, however, initiated a cultural breakthrough for

Americans as representations of Egyptian culture flooded western museums and publications,

sparking a growing interest in all things Egyptian that was coined Egyptomania.

As Egyptomania swept over the West, a relatively young America began assimilating

Egyptian culture into its own national identity, creating a hybrid national heritage that

would vastly affect the memorial landscape of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Far more than a study of Egyptian revivalism, this book examines the Egyptian style

of commemoration from the rural cemetery to national obelisks to the Sphinx at Mount

Auburn Cemetery. Giguere argues that Americans adopted Egyptian forms of commemoration

as readily as other neoclassical styles such as Greek revivalism, noting that the

American landscape is littered with monuments that define the Egyptian style’s importance

to American national identity. Of particular interest is perhaps America’s greatest

commemorative obelisk: the Washington Monument. Standing at 555 feet high and

constructed entirely of stone—making it the tallest obelisk in the world—the Washington

Monument represents the pinnacle of Egyptian architecture’s influence on America’s desire

to memorialize its national heroes by employing monumental forms associated with

solidity and timelessness. Construction on the monument began in 1848, but controversy

over its design, which at one point included a Greek colonnade surrounding the obelisk,

and the American Civil War halted construction until 1877. Interestingly, Americans saw

the completion of the Washington Monument after the Civil War as a mending of the

nation itself, melding Egyptian commemoration with the reconstruction of America.

As the twentieth century saw the rise of additional commemorative obelisks, the Egyptian

Revival became ensconced in American national identity. Egyptian-style architecture

has been used as a form of commemoration in memorials for World War I and II, the civil

rights movement, and even as recently as the 9/11 remembrances. Giguere places the Egyptian

style in a historical context that demonstrates how Americans actively sought to forge

a national identity reminiscent of Egyptian culture that has endured to the present day.

See other books on: Architecture | Architecture and society | Monuments | National Identity | Nationalism and architecture

See other titles from University of Tennessee Press