23 start with S start with S

Sufism, the mystical path of Islam, is a key feature of the complex Islamic culture of South Asia today. Influenced by philosophies and traditions from other Muslim lands and by pre-Islamic rites and practices, Sufism offers a corrective to the image of Islam as monolithic and uniform.

In Sacred Spaces, Pakistani artist and educator Samina Quraeshi provides a locally inflected vision of Islam in South Asia that is enriched by art and by a female perspective on the diversity of Islamic expressions of faith. A unique account of a journey through the author’s childhood homeland in search of the wisdom of the Sufis, the book reveals the deeply spiritual nature of major centers of Sufism in the central and northwestern heartlands of South Asia. Illuminating essays by Ali S. Asani, Carl W. Ernst, and Kamil Khan Mumtaz provide context to the journey, discussing aspects of Sufi music and dance, the role of Sufism in current South Asian culture and politics, and the spiritual geometry of Sufi architecture.

Quraeshi relies on memory, storytelling, and image making to create an imaginative personal history using a rich body of photographs and works of art to reflect the seeking heart of the Sufi way and to demonstrate the diversity of this global religion. Her vision builds on the centuries-old Sufi tradition of mystical messages of love, freedom, and tolerance that continue to offer the promise of building cultural and spiritual bridges between peoples of different faiths.

The Northwestern Shoshone knew as home the northern Great Salt Lake, Bear River, Cache, and Bear Lake valleys of northern Utah. Sagwitch was born at a time when his people traded with the mountain men. In the late 1850s, wagons brought Mormon farmers to settle in Cache Valley, the Northwestern Shoshone heartland. Emigrants and settlers reduced Shoshone access to traditional village sites and food resources. Relationships with the Mormons were mostly good but often strained, and the Shoshone treatment of migrants, who now traveled north and south as well as west and east through the area, was increasingly opportunistic. It only took a few violent incidents for a zealous army colonel to seek severe punishment of the Northwestern Shoshone on a winter morning in 1863. The Bear River Massacre was among the bloodiest engagements of America's Indian wars. Hundreds of Shoshone, including Sagwitch's wife and two sons, died; Sagwitch was wounded but escaped. The band was shattered, other chiefs dead.

The following years were very hard for the survivors. The federal government negotiated a treaty with them but failed to get Sagwitch's signature when, en route to the sessions, he was arrested and then wounded by a white assassin. With the world around him changed, Sagwitch sought accommodation with the most immediate threat to his people's traditional way of survival—the Mormons occupying the Shoshone's valleys.

This, then, is also the story of the conversion of Sagwitch and his band to the Mormon Church. Though not without problems, that conversion was long lasting and thorough. Sagwitch and other Shoshone would demonstrate in important ways their new religious devotion. With the assistance of Mormon leaders, they established the Washakie community in northern Utah. Though efforts to secure a land base had an uneven history, they partly succeeded, and the story of these Shoshone's attempts at rural farming diverged significantly from what happened on government reservations. When Sagwitch died, his death went almost unnoticed outside of Washakie, but his children and grandchildren continued to be important voices among a people who, after experiencing near annihilation, survived in the new world into which Sagwitch led them.

An iconic figure of the Asian American movement, Richard Aoki (1938–2009) was also, as the most prominent non-Black member of the Black Panther Party, a key architect of Afro-Asian solidarity in the 1960s and ’70s. His life story exposes the personal side of political activism as it illuminates the history of ethnic nationalism and radical internationalism in America.

A reflection of this interconnection, Samurai among Panthers weaves together two narratives: Aoki’s dramatic first-person chronicle and an interpretive history by a leading scholar of the Asian American movement, Diane C. Fujino. Aoki’s candid account of himself takes us from his early years in Japanese American internment camps to his political education on the streets of Oakland, to his emergence in the Black Panther Party. As his story unfolds, we see how his parents’ separation inside the camps and his father’s illegal activities shaped the development of Aoki’s politics. Fujino situates his life within the context of twentieth-century history—World War II, the Cold War, and the protests of the 1960s. She demonstrates how activism is both an accidental and an intentional endeavor and how a militant activist practice can also promote participatory democracy and social service.

The result of these parallel voices and analysis in Samurai among Panthers is a complex—and sometimes contradictory—portrait of a singularly extraordinary activist and an expansion and deepening of our understanding of the history he lived.

With a recurring focus on how his mother’s tragic weaknesses and her compelling strengths affected his development, Awkward intersperses the chronologically arranged autobiographical sections with ruminations on his own interests in literary and cultural criticism. As a male scholar who has come under fire for describing himself as a feminist critic, he reflects on such issues as identity politics and the politics of academia, affirmative action, and the Million Man March.

By connecting his personal experiences with larger political, cultural, and professional questions, Awkward uses his life as a palette on which to blend equations of race and reading, urbanity and mutilation, alcoholism, pain, gender, learning, sex, literature, and love.

For the first four years of his life, Prahlad didn’t speak. But his silence didn’t stop him from communicating—or communing—with the strange, numinous world he found around him. Ordinary household objects came to life; the spirits of long-dead slave children were his best friends. In his magical interior world, sensory experiences blurred, time disappeared, and memory was fluid. Ever so slowly, he emerged, learning to talk and evolving into an artist and educator. His journey takes readers across the United States during one of its most turbulent moments, and Prahlad experiences it all, from the heights of the Civil Rights Movement to West Coast hippie enclaves to a college town that continues to struggle with racism and its border state legacy.

Rooted in black folklore and cultural ambience, and offering new perspectives on autism and more, The Secret Life of a Black Aspie will inspire and delight readers and deepen our understanding of the marginal spaces of human existence.

Witness the Civil Rights Movement through the eyes of two children.

Sheyann Webb was eight years old and Rachel West was nine when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. arrived in Selma, Alabama, on January 2, 1965. He came to organize non-violent demonstrations against discriminatory voting laws. Selma, Lord, Selma is their firsthand account of the events from that turbulent winter of 1965--events that changed not only the lives of these two little girls but the lives of all Alabamians and all Americans. From 1975 to 1979, award-winning journalist Frank Sikora conducted interviews with Webb and West, weaving their recollections into this luminous story of fear and courage, struggle and redemption that readers will discover is Selma, Lord, Selma.

On February 15, 1851, Shadrach Minkins was serving breakfast at a coffeehouse in Boston when history caught up with him. The first runaway to be arrested in New England under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, this illiterate Black man from Virginia found himself the catalyst of one of the most dramatic episodes of rebellion and legal wrangling before the Civil War. In a remarkable effort of historical sleuthing, Gary Collison has recovered the true story of Shadrach Minkins’ life and times and perilous flight. His book restores an extraordinary chapter to our collective history and at the same time offers a rare and engrossing picture of the life of an ordinary Black man in nineteenth-century North America.

As Minkins’ journey from slavery to freedom unfolds, we see what day-to-day life was like for a slave in Norfolk, Virginia, for a fugitive in Boston, and for a free Black man in Montreal. Collison recreates the drama of Minkins’s arrest and his subsequent rescue by a band of Black Bostonians, who spirited the fugitive to freedom in Canada. He shows us Boston’s Black community, moved to panic and action by the Fugitive Slave Law, and the previously unknown community established in Montreal by Minkins and other refugee Blacks from the United States. And behind the scenes, orchestrating events from the disastrous Compromise of 1850 through the arrest of Minkins and the trial of his rescuers, is Daniel Webster, who through the exigencies of his dimming political career, took the role of villain.

Webster is just one of the familiar figures in this tale of an ordinary man in extraordinary circumstances. Others, such as Frederick Douglass, Richard Henry Dana, Jr., Harriet Jacobs, and Harriet Beecher Stowe (who made use of Minkins’s Montreal community in Uncle Tom’s Cabin), also appear throughout the narrative. Minkins’ intriguing story stands as a fascinating commentary on the nation’s troubled times—on urban slavery and Boston abolitionism, on the Underground Railroad, and on one of the federal government’s last desperate attempts to hold the Union together.

n 1968, Tommie Smith and his teammate John Carlos won the gold and silver medals, respectively, for the 200 meter dash. Receiving their medals on the dais, they raised their fists and froze a moment in time that will forever be remembered as a powerful day of protest. In this, his autobiography, Smith tells the story of that moment, and of his life before and after it, to explain what that moment meant to him.

In Silent Gesture, Smith recounts his life before and after the 1968 Olympics: his life-long commitment to athletics, education, and human rights. He dispels some of the myths surrounding his and Carlos' act on the dais -- contrary to legend, Smith wasn't a member of the Black Panthers, but a member of the US Olympic Project for Human Rights -- and describes in detail the planning and risks involved in his protest. Smith also details his many years after Mexico City of devotion to human rights, athletics, and education. A unique resource for anyone concerned with international sports, history, and the African American experience, Silent Gesture contributes a complete picture of one of the most famous moments in sports history, and of a man whose actions always matched his words.

This book is the first anthology of the autobiographical writings of Peter Randolph, a prominent nineteenth-century former slave who became a black abolitionist, pastor, and community leader.

Randolph’s story is unique because he was freed and relocated from Virginia to Boston, along with his entire plantation cohort. A lawsuit launched by Randolph against his former master’s estate left legal documents that corroborate his autobiographies.

Randolph's writings give us a window into a different experience of slavery and freedom than other narratives currently available and will be of interest to students and scholars of African American literature, history, and religious studies, as well as those with an interest in Virginia history and mid-Atlantic slavery.

Slavery’s Descendants brings together contributors from a variety of racial backgrounds, all members or associates of a national racial reconciliation organization called Coming to the Table, to tell their stories of dealing with America’s racial past through their experiences and their family histories. Some are descendants of slaveholders, some are descendants of the enslaved, and many are descendants of both slaveholders and slaves. What they all have in common is a commitment toward collective introspection, and a willingness to think critically about how the nation’s histories of oppression continue to ripple into the present, affecting us all.

The stories in Slavery’s Descendants deal with harrowing topics—rape, lynching, cruelty, shame—but they also describe acts of generosity, gratitude, and love. Together, they help us confront the legacy of slavery to reclaim a more complete picture of U.S. history, one cousin at a time.

Funding for the production of this book was provided by Furthermore, a program of the J. M. Kaplan Fund (https://www.furthermore.org).

Originally published 35 years ago, Soulside became an urban anthropological classic. The book helped to dispel many false impressions about ghetto life and questioned the idea, precipitated in the influential Moynihan Report and in notions of a "culture of poverty," that the poor had chosen to lead the lives they do. Raising central moral and political questions about American society in a turbulent period, Soulside became an example of public engagement in anthropology. In a new afterword, Ulf Hannerz discusses the book's place in the debates of the time and its relevance to current arguments in anthropology.

New edition available: Sounds Like Home: Growing Up Black and Deaf in the South, 20th Anniversary Edition, ISBN 978-1-944838-58-4

Features a new introduction by scholars Joseph Hill and Carolyn McCaskill

Mary Herring Wright’s memoir adds an important dimension to the current literature in that it is a story by and about an African American deaf child. The author recounts her experiences growing up as a deaf person in Iron Mine, North Carolina, from the 1920s through the 1940s. Her story is unique and historically significant because it provides valuable descriptive information about the faculty and staff of the North Carolina school for Black deaf and blind students from the perspective of a student as well as a student teacher. In addition, this engrossing narrative contains details about the curriculum, which included a week-long Black History celebration where students learned about important Blacks such as Madame Walker, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and George Washington Carver. It also describes the physical facilities as well as the changes in those facilities over the years. In addition, Sounds Like Home occurs over a period of time that covers two major events in American history, the Depression and World War II.

Wright’s account is one of enduring faith, perseverance, and optimism. Her keen observations will serve as a source of inspiration for others who are challenged in their own ways by life’s obstacles.

In Sown in Earth, Arroyo often roots his thoughts and feelings in place, expressing a deep connection to the small homes he inhabited in his childhood, his warm and hazy memories of his grandmother’s kitchen in Puerto Rico, the rivers and creeks he fished, and the small cafés in Madrid that inspired writing and reflection in his adult years. Swirling in romantic moments and a refined love for literature, Arroyo creates a sense of belonging and appreciation for his life despite setbacks and complex anxieties along the way.

By crafting a written journey through childhood traumas, poverty, and the impact of alcoholism on families, Fred Arroyo clearly outlines how his lived experiences led him to become a writer. Sown in Earth is a shocking yet warm collage of memories that serves as more than a memoir or an autobiography. Rather, Arroyo recounts his youth through lyrical prose to humanize and immortalize the hushed lives of men like his father, honoring their struggle and claiming their impact on the writers and artists they raised.

As readers of his Long Distance Love know, Grant Farred has been a supporter of the English Premier League club, Liverpool Football Club, for decades. His fandom for that team launched an unexpected connection with a world beyond the limits of the apartheid state of his upbringing in South Africa. However, A Sports Odyssey shows that as Farred’s fervor for Liverpool ended, he developed a new set of sports attachments in Ithaca, New York: to his son’s youth basketball career, to the men’s basketball team at Cornell University and its coach, and even to professional teams like the New York Knicks. Farred’s bemusement at finding himself a sports parent, a New Yorker, and a company man, only underline the sincerity of his affections.

In A Sports Odyssey, Farred writes elegantly and eloquently about how sports and sports fandom create a sense of belonging, but also loss. This is a heartfelt examination of how we find “home” in who and what we love.

In the series Sporting

Millions of innocent people were arrested in Stalin’s Soviet Union during the 1930s in different waves of mass repression. Under violent interrogation, many were forced to confess to crimes they did not commit. Rather than save their lives, as the interrogators had promised, confession was usually the last step to their execution. Very few of those arrested eventually refused to confess.

Oleksandr Shums’kyi, the Ukrainian Marxist revolutionary, was one of the most important but least known of them. He not only refused to confess but sustained for over a decade a massive protest against his repression and the Stalinist attack on his country, Ukraine. Stalin punished him mercilessly in response, paralyzing him in jail and murdering his wife, but refrained from assassinating him for more than ten years.

This book unravels the Shums’kyi riddle to explain why. In doing so, it opens a new window into understanding the history of Soviet repression and the Russian pathologies toward Ukrainian independence, which help us understand Russia’s current war against Ukraine.

Stanley Kubrick reexamines the director’s work in context of his ethnic and cultural origins. Focusing on several of Kubrick’s key themes—including masculinity, ethical responsibility, and the nature of evil—it demonstrates how his films were in conversation with contemporary New York Jewish intellectuals who grappled with the same concerns. At the same time, it explores Kubrick’s fraught relationship with his Jewish identity and his reluctance to be pegged as an ethnic director, manifest in his removal of Jewish references and characters from stories he adapted.

As he digs deep into rare Kubrick archives to reveal insights about the director’s life and times, film scholar Nathan Abrams also provides a nuanced account of Kubrick’s cinematic artistry. Each chapter offers a detailed analysis of one of Kubrick’s major films, including Lolita, Dr. Strangelove, 2001, A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and Eyes Wide Shut. Stanley Kubrick thus presents an illuminating look at one of the twentieth century’s most renowned and yet misunderstood directors.

The Oregon Coast is a rugged, beautiful region. Separated from the state’s population centers by the Coast Range, it is a land of small towns reliant primarily on fishing and tourism, known for its dramatic landscapes and dramatic storms. Many of the stories Tobias covered were tragedies: car crashes, falls, drownings, capsizings. And those are just the accidents; Tobias covered plenty of violent crimes as well. But her stories also include more lighthearted moments, including her own experiences learning to live on and cover the coast. Tobias’s story is as much her own as it is the coast’s; she takes the reader through familiar beats of life (regular trips back east as her parents age), the decline of journalism in the twenty-first century, and the unexpected (and not entirely glamorous) experiences of a working reporter—such as a bout of vertigo after rappelling from a helicopter onto a ship. Ultimately, Tobias tells a compelling story of a region that many visit but few truly know.

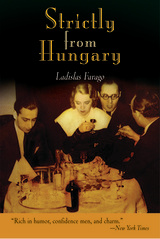

Known for his best-selling military histories, Ladislas Farago also wrote a witty tribute to his homeland, Strictly from Hungary. Noting that Hungary has produced some of the world's most renowned artists, scientists, and financiers as well as its share of world-class con-artists, charlatans, and rakes, Farago sets out to explain just how one tiny country can be responsible for so much talent, both good and bad. Using stories from his days as a struggling writer in the bustling café scenes of Budapest and New York City, Farago demonstrates the Hungarian knack for remaining irrepressible and optimistic even in the face of catastrophe. Here we meet Zoltan, a fellow Bohemian who presents his astonished benefactor with a play "about nothing," a theme later made famous by another writer of Hungarian descent, Jerry Seinfeld. Farago also introduces us to "Baby Kiss," a vivacious Hungarian beauty queen, and the story of how she ended up in Fort Worth, Texas; Orkeny, a double agent for America at the height of the Cold War who "spiced up" his reports to keep everyone happy, and the author's own experience getting mustered into the supposedly non-existent Royal Hungarian Army. Farago's reminiscence validates what most Hungarians believe: that Hungary is the center of the world and that everyone has some connection to the land of the Magyars. In that spirit, Farago learns that George Washington himself was "strictly from Hungary." This edition is introduced by the author's son, who shows that the same vibrant spirit described by his father remains the hallmark of the Hungarian temperament.

McDaniel compares the mortality rates of the emigrants to those of other migrants to tropical areas. He finds that, contrary to popular belief, black immigrants during this period died at unprecedented rates. Moreover, he shows that though the emigrant's mortality levels were exceptionally high, their mortality patterns were consistent with those of other populations.

McDaniel concludes that the greater the variance between the environment left and the environment entered, the higher the probability of contracting a new disease, and, in some cases, of death from these diseases. Additionally, a migrant's health can be affected by dietary changes, differences in local pathogens, inappropriate immunities, and increased risk of accidents due to unfamiliar surroundings.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press