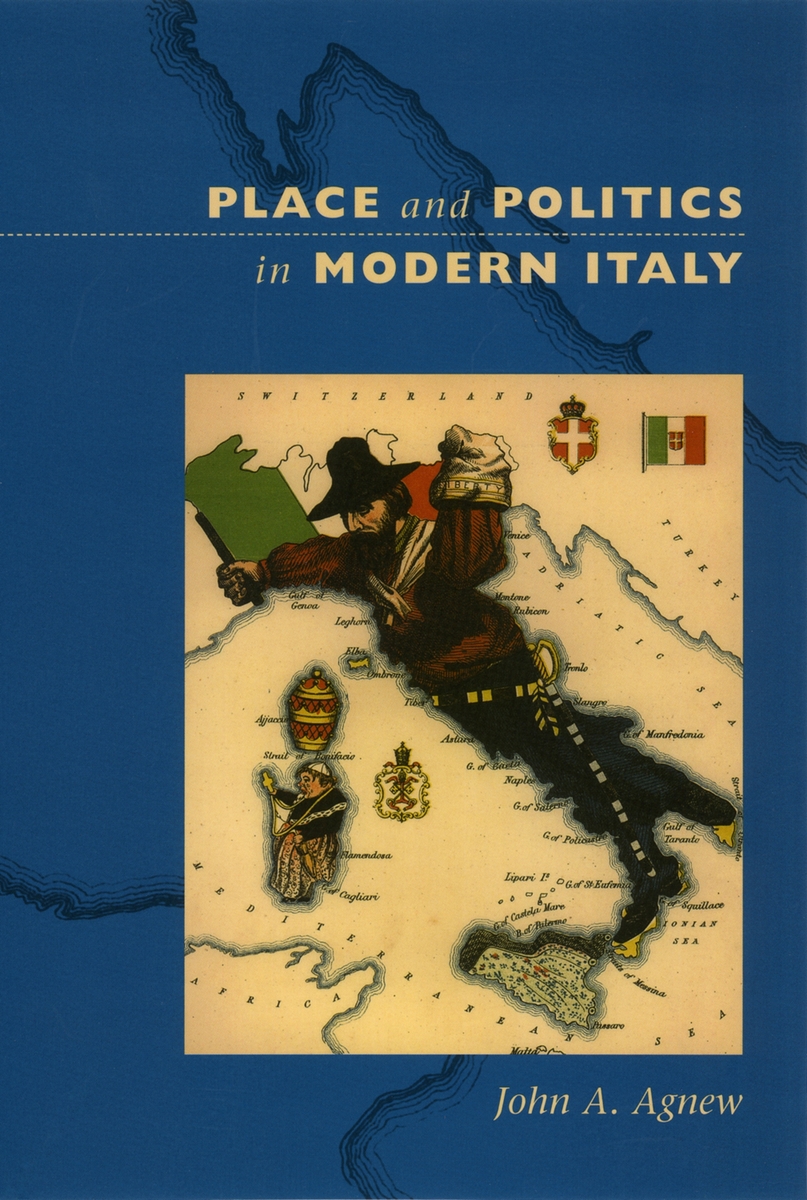

Place and Politics in Modern Italy

by John A. Agnew

University of Chicago Press, 2002

Cloth: 978-0-226-01053-3 | Paper: 978-0-226-01051-9

Library of Congress Classification JN5451.A63 2002

Dewey Decimal Classification 320.945

Cloth: 978-0-226-01053-3 | Paper: 978-0-226-01051-9

Library of Congress Classification JN5451.A63 2002

Dewey Decimal Classification 320.945

ABOUT THIS BOOK | AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY | TOC | EXCERPT | REQUEST ACCESSIBLE FILE

ABOUT THIS BOOK

How do the places where people live help structure and restructure their sociopolitical identities and interests? In this book, renowned political geographer John A. Agnew presents a theoretical model that addresses the relation of place to politics and applies it to a series of historicogeographical case studies set in modern Italy.

For Agnew, place is not just a static backdrop against which events occur, but a dynamic component of social, economic, and political processes. He shows, for instance, how the lack of a common "landscape ideal" or physical image of Italy delayed the development of a sense of nationhood among Italians after unification. And Agnew uses the post-1992 victory of the Northern League over the Christian Democrats in many parts of northern Italy to explore how parties are replaced geographically during periods of intense political change.

Providing a fresh new approach to studying the role of space and place in social change, Place and Politics in Modern Italy will interest geographers, political scientists, and social theorists.

For Agnew, place is not just a static backdrop against which events occur, but a dynamic component of social, economic, and political processes. He shows, for instance, how the lack of a common "landscape ideal" or physical image of Italy delayed the development of a sense of nationhood among Italians after unification. And Agnew uses the post-1992 victory of the Northern League over the Christian Democrats in many parts of northern Italy to explore how parties are replaced geographically during periods of intense political change.

Providing a fresh new approach to studying the role of space and place in social change, Place and Politics in Modern Italy will interest geographers, political scientists, and social theorists.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

John A. Agnew is a professor of geography at the University of California, Los Angeles. He is the author or coauthor of a number of books, most recently Geopolitics: Re-visioning World Politics and The Geogrpahy of the World Economy, third edition.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Figures

List of Tables

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations for Names

1. Introduction

2. Mapping Politics Theoretically

3. Landscape Ideals and National Identity in Italy

4. Modernization and Italian Political Development

5. The Geographical Dynamics of Italian Electoral Politics, 1948-87

6. Red, White, and Beyond: Place and Politics in Pisoia and Lucca

7. The Geography of Party Replacement in Northern Italy, 1987-96

8. The Northern League and Political Identity in Northern Italy

9. Reimagining Italy after the Collapse of the Party System in 1992

10. Place and Understanding in Italian Politics

Notes

Bibliography

Index

List of Tables

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations for Names

1. Introduction

2. Mapping Politics Theoretically

3. Landscape Ideals and National Identity in Italy

4. Modernization and Italian Political Development

5. The Geographical Dynamics of Italian Electoral Politics, 1948-87

6. Red, White, and Beyond: Place and Politics in Pisoia and Lucca

7. The Geography of Party Replacement in Northern Italy, 1987-96

8. The Northern League and Political Identity in Northern Italy

9. Reimagining Italy after the Collapse of the Party System in 1992

10. Place and Understanding in Italian Politics

Notes

Bibliography

Index

EXCERPT

CHAPTER 1: Introduction

MAPPING POLITICS

Mapping politics involves showing how political identities and interests are structured geographically as the result of human agency in the places where people live. Human agency and the changing conditions under which that agency takes place, however, mean that mapping is never complete. Just as a map comes into focus, it is transformed into another one. In recent years the pace of geographical change in Europe and North America seems to have increased after a long period following World War II when the geographies of political identity and political interests looked fairly stable. This book provides a theoretical framework for addressing the conception of "mapping politics" and a set of historical-geographical case studies of modern Italy--since 1870, but with a more specific focus on the years since World War II--to illustrate the efficacy of the approach and to offer a distinctive perspective on the course of modern Italian politics. In so doing it also engages some of the major debates in contemporary political studies.

Perhaps the most important debate in contemporary political studies is over interpretations of the trend toward a world organized increasingly in terms of the flow of goods, messages, capital, and people across widely dispersed networks and, on the other hand, the continuing division of the world into national states that provide the main regulatory framework for these networks and the primary source of political identity for much of the world's population. There is something of an intellectual standoff between two sides in a debate over this tension: between those perhaps overstating the novelty and overall impact of networks and those who may remain too committed to the enduring significance of national territories. Part of the problem is the way the debate is posed, as if networks invariably stand in opposition to territories. This is the case only if networks are seen as a completely new phenomenon without geographical anchors in particular places and if all territories are seen as national ones.

Yet there is another way of looking at politics without ending up in the current impasse of "networks versus territories." This approach is to see politics as organized in terms of the places where most people live their lives; settings that are linked together and across geographical scales by networks of political and economic influence that have been, and still are, bounded by but decreasingly limited to the territories of national states. The novelty of globalization can be exaggerated, however. From one point of view, the social world has been global in various ways since the sixteenth century, when European imperialism began its global march. But social science in the twentieth century has resolutely privileged the national as a singular scale of analysis when actual domestic and international politics presuppose the coeval importance of other geographical scales (such as the local and the global).

Beyond the debate over networks versus territories and the national versus the global, current Anglo-American debates over the nature of politics are dominated by three schools of thought. These are called the rational actor, political culture, and multiculturalist schools, although there are different emphases within each grouping. To rational actor theorists, politics simply reflects and amplifies individual preferences. People are seen as perpetually engaged in maximizing their welfare whatever the context of life. The only "real" actors are individuals, who act politically by matching their preferences to this or that political ideology or to the promises made by this or that politician. Politics always reduces to the pursuit of individual self-interest. For political culture theorists, politics is more about the clash of values than the clash of interests. The "best" politics involves pursuing values that emerge from reasoned deliberation within social groups dependent on habits of mutual trust. Community and dialogue more than preferences and interests are the catchwords of this persuasion. But all politics is ultimately about the way groups associate to establish and articulate different values and then attempt to realize them through political action. Finally, multiculturalists see the groups we are cast into by virtue of race, ethnicity, language, or culture as fundamental to political mobilization and action. Such groups are ascriptive rather than voluntary. The identities groups provide precede both preferences and association. Politics is about gaining recognition for one's identity and then using it as a resource in struggles over material and symbolic interests.

A central claim of this book is not that these accounts are wrong but that they are radically incomplete in their understanding of how preferences, interests, values, identities, and thus politics come about. They abstract preferences, values, and so on from the spatial settings or places where they are realized. Politics is always part, but only part, of the complex lives of people who interact in a variety of groups that they cooperate with daily (families, associations, political organizations, fellow workers, businesses, churches) and that help socialize them into certain political dispositions rather than others.

The ties sustained by groups can be relatively strong if everyday life is dominated by a single group or by groups that have cross-memberships. But a feature of modernity is that most group memberships are extraordinarily fluid and crosscutting, with relatively weak ties between any one group and its members. Typically, therefore, values and preferences emerge from fractionated and differentiated group experiences in which identities are forged and remade through shifting voluntary self-affiliations. From day to day, the seemingly abstract processes of political disposition and mobilization are concretely grounded in the practical routines and institutional channels of the workaday world. For most people these are typically concentrated around definite geographical sites, though these are invariably linked into wider webs or networks through which groups and individuals are organized over larger areas such as regions, states, and the world. The identities, values, and preferences that inspire particular kinds of political action therefore are embedded in the places or geographical contexts where people live their lives.

The book develops this theory of "mapping politics" in relation to the empirical exploration of the politics of modern Italy. Italian politics is often seen as expressing either the timeless features of political culture (national or regional) whose origins lie in the primordial mists of the distant past or else the slow and agonized achievement of a national politics of individual preferences in the face of entrenched institutions and political practices committed to sustaining social and regional identities that work against national unity and common political purpose. Such perspectives are readily comparable to the political culture and rational actor theories mentioned previously. In their stead, and throughout this book, I propose a perspective that sees Italy's national space as being in historical flux, without presuming either fixed regional cultures or an emerging national politics of individual preferences.

Previous accounts have tended to see local geographical differences as representing the past either as inscribed in the contemporary political landscape or as residual to a present that is increasingly homogenized and nationalized. Alternatively, however, group membership is realized, identities are formed, and preferences are defined in shifting geographical settings, or places, that have different local and long-distance linkages over time. From this point of view geography is dynamic rather than static. It refers to the ways life processes impinge on politics as their local and long-distance components change over time rather than operating within fixed, permanent geographical parameters such as those set down by current national-state boundaries or historical regional designations. Much contemporary social science depends implicitly on the prior and unexamined valorization of geographical units of account (the state, the city, administrative regions) and thereby occludes the possibility of seeing politics (or other phenomena) as geographically dynamic.

WHY ITALY?

The focus on Italian politics might be seen as biasing the case in favor of the perspective of geographical dynamics. After all, Italy is usually seen as very unlike the rest of Europe or the industrial-capitalist world in general. It is notoriously divided geographically, socially, and politically.

Notwithstanding the limited appropriateness of a charge of bias, Italy does have a number of advantages as a focus for the general argument of the book. One is that Italian scholars have been intrigued by the differences between regions and localities within the country, from themeridionalisti (students of the South) of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the great Marxist thinker Antonio Gramsci (1892-1936) (on city/countryside and north/south development gaps) to contemporary political scientists, geographers, and sociologists addressing rural/urban, regional, and local differences. There is thus a vast storehouse of information available about Italy's internal geography and how scholars have tried to explain it. Another advantage is that Italy does contrast with other European countries (and the United States) in popular and intellectual self-consciousness about its political-geographical difficulties. In this respect, the only other example that immediately comes to mind is Canada, a country so perpetually on the verge of coming apart that the mystery of its continuing unity is the central question for Canadian social scientists. The question of political identity is more openly available for public discussion in Italy than elsewhere because of both the relative recency of Italian national identity (Italy unified only in the 1860s) and its problematic character. Finally, Italy has adapted to recent changes in the world economy, associated with the coming of the European Union and the explosion of economic transactions between businesses across national boundaries, in ways that seem to have increased geographical differentiation within the country. Local external economies of scale (associated with skilled labor pools, training schemes, artisan traditions, and supplier contacts) and local social interdependence have been important in producing specialized economies in many parts of the country. But other areas have lagged behind or have been left out of this trend, thus stimulating even more local and regional economic differences with potential political impact.

THEMES OF PLACE AND POLITICS

Four themes can be identified that cut across all chapters to provide the links between the empirical material on Italian politics and understandings of it (in chapters 3-9) and the theory of mapping politics (in chapter 2).

Place and Scale

The first theme concerns the way geographical differences are understood and interpreted. Rather than a "metric" space, divided into compact areas, place involves a conception of topological space in which diverse geographical scales are brought together through networks of internal (locale) and external (location) ties in defining geographical variation in social characteristics. People also invest meaning in the places they inhabit. The scales by which they identify themselves and their group memberships (national, local, international) vary both from country to country and over time. Since the nineteenth century in Europe the national scale has often been presumed as the scale for establishing primary political identity. But sense of place at the national scale can coexist with or be replaced by alternative ones. Existing geographical variation in a given phenome-non--party vote, geographical sense of political identity, and so forth-- responds to changes in the interaction of networks that interweave the internal and the external to produce new geographical variation in the same phenomenon over time.

In other words, geographical variation cannot simply be read off one geographical scale, and it changes over time as the balance of influences across scales changes. Place differences therefore are a necessary concomitant to the interrelation of social, economic, and political processes across scales that come together or are mediated through the cultural practices of existing settings. In this way geography is inherent in or constitutive of social processes rather than merely a backdrop on which they are inscribed.

Why has this sort of perspective rarely achieved much emphasis among social scientists or historians? For one thing, the concept of place became fatefully identified with that of community at the turn of the twentieth century when the current intellectual division of labor among social science disciplines was largely established. When community was viewed as in decline under the impact of industrialization and urbanization (and more recently the effects of new communication technologies such as cell phones and the Internet), place was eclipsed too. At the same time "society," rather than remaining solely an abstraction or ideal type, was defined in practical terms as coterminous with the national state. A single geographical scale--that of the national state--thus became the geographical base on which much social science was founded.

In addition, dominant representations of terrestrial space have followed the identity that grew up in the nineteenth century between abstraction and scientific validity. Geographical variation, multicausal explanations, local specificity, and vernacular understandings are all antithetical to the concept of space either as national chunks or as the result of structural relations (for example, in the core/periphery relations of subordination and incorporation of world systems and dependency theories). "Science" is about finding causal relations that either are independent of time and space or vary predictably across area types or between time periods. In fact what often happens is that uniformity is imposed by selecting taken-for-granted geographic units and holding numerous potential causal variables ceteris paribus (as if their effects were not present) so that universality can then be discovered.

The distinction between different geographical scales or levels has also been a problem because they have served to distinguish various areas of study (such as international relations versus domestic politics or micro-versus macroeconomics) and levels of generalization and causality (ecological versus individual inference) rather than complexly related dimensions of the contexts in which actual social and political processes occur. Integrating scales is difficult or even heretical when different fields determine their specialty by basing their uniqueness on different scales and when analysis (reducing explanation to the simplest level) has tended to win out over synthesis (putting together elements of explanation that emerge across a range of scales).

Finally, representations of space and how we think they figure in understanding politics or other social phenomena are not merely epis-temic--functions of how we just happen to think. They are closely related to the dominant political and material conditions of the eras when they are articulated. But they often live on after those eras have closed because of intellectual inertia and the closed character of the intellectual tribes that dominate different fields. Much contemporary social science is still steeped in the theories and representations of space of such nineteenth-century founding fathers as Marx, Durkheim, and Weber. Notwithstanding the legitimating quotation from Durkheim I offer at the beginning of the chapter, none of these luminaries had much to say to the enterprise of integrating scales of analysis into the concept of place. Yet the complexities of social life in a globalizing world require nothing less.

Historical Contingency

Since the late nineteenth century, Anglo-American political science has been trying to escape from the twin constraints of time and space by searching for empirical regularities that are independent of both. The goal has been to imitate an image of physics or mathematics as fields that made abstractions beyond the confines of the everyday and that were widely admired among academics for the causal simplicity, mathematical elegance, and aesthetic brilliance of their discoveries. Associated with this has been the drive to construct a state-centered applied social science that would better manage the various problems encountered during state formation.

Space is not the vague and undetermined medium which Kant imagined. Spatial coordination consists essentially in a primary coordination of the data of sensuous experience. To dispose things spatially there must be the possibility of placing them differently. This is to say space could not be what it was if it were not divided and differentiated. But whence come these divisions? . . . evidently from the fact that different sympathetic values have been attributed to different regions

--Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life

MAPPING POLITICS

Mapping politics involves showing how political identities and interests are structured geographically as the result of human agency in the places where people live. Human agency and the changing conditions under which that agency takes place, however, mean that mapping is never complete. Just as a map comes into focus, it is transformed into another one. In recent years the pace of geographical change in Europe and North America seems to have increased after a long period following World War II when the geographies of political identity and political interests looked fairly stable. This book provides a theoretical framework for addressing the conception of "mapping politics" and a set of historical-geographical case studies of modern Italy--since 1870, but with a more specific focus on the years since World War II--to illustrate the efficacy of the approach and to offer a distinctive perspective on the course of modern Italian politics. In so doing it also engages some of the major debates in contemporary political studies.

Perhaps the most important debate in contemporary political studies is over interpretations of the trend toward a world organized increasingly in terms of the flow of goods, messages, capital, and people across widely dispersed networks and, on the other hand, the continuing division of the world into national states that provide the main regulatory framework for these networks and the primary source of political identity for much of the world's population. There is something of an intellectual standoff between two sides in a debate over this tension: between those perhaps overstating the novelty and overall impact of networks and those who may remain too committed to the enduring significance of national territories. Part of the problem is the way the debate is posed, as if networks invariably stand in opposition to territories. This is the case only if networks are seen as a completely new phenomenon without geographical anchors in particular places and if all territories are seen as national ones.

Yet there is another way of looking at politics without ending up in the current impasse of "networks versus territories." This approach is to see politics as organized in terms of the places where most people live their lives; settings that are linked together and across geographical scales by networks of political and economic influence that have been, and still are, bounded by but decreasingly limited to the territories of national states. The novelty of globalization can be exaggerated, however. From one point of view, the social world has been global in various ways since the sixteenth century, when European imperialism began its global march. But social science in the twentieth century has resolutely privileged the national as a singular scale of analysis when actual domestic and international politics presuppose the coeval importance of other geographical scales (such as the local and the global).

Beyond the debate over networks versus territories and the national versus the global, current Anglo-American debates over the nature of politics are dominated by three schools of thought. These are called the rational actor, political culture, and multiculturalist schools, although there are different emphases within each grouping. To rational actor theorists, politics simply reflects and amplifies individual preferences. People are seen as perpetually engaged in maximizing their welfare whatever the context of life. The only "real" actors are individuals, who act politically by matching their preferences to this or that political ideology or to the promises made by this or that politician. Politics always reduces to the pursuit of individual self-interest. For political culture theorists, politics is more about the clash of values than the clash of interests. The "best" politics involves pursuing values that emerge from reasoned deliberation within social groups dependent on habits of mutual trust. Community and dialogue more than preferences and interests are the catchwords of this persuasion. But all politics is ultimately about the way groups associate to establish and articulate different values and then attempt to realize them through political action. Finally, multiculturalists see the groups we are cast into by virtue of race, ethnicity, language, or culture as fundamental to political mobilization and action. Such groups are ascriptive rather than voluntary. The identities groups provide precede both preferences and association. Politics is about gaining recognition for one's identity and then using it as a resource in struggles over material and symbolic interests.

A central claim of this book is not that these accounts are wrong but that they are radically incomplete in their understanding of how preferences, interests, values, identities, and thus politics come about. They abstract preferences, values, and so on from the spatial settings or places where they are realized. Politics is always part, but only part, of the complex lives of people who interact in a variety of groups that they cooperate with daily (families, associations, political organizations, fellow workers, businesses, churches) and that help socialize them into certain political dispositions rather than others.

The ties sustained by groups can be relatively strong if everyday life is dominated by a single group or by groups that have cross-memberships. But a feature of modernity is that most group memberships are extraordinarily fluid and crosscutting, with relatively weak ties between any one group and its members. Typically, therefore, values and preferences emerge from fractionated and differentiated group experiences in which identities are forged and remade through shifting voluntary self-affiliations. From day to day, the seemingly abstract processes of political disposition and mobilization are concretely grounded in the practical routines and institutional channels of the workaday world. For most people these are typically concentrated around definite geographical sites, though these are invariably linked into wider webs or networks through which groups and individuals are organized over larger areas such as regions, states, and the world. The identities, values, and preferences that inspire particular kinds of political action therefore are embedded in the places or geographical contexts where people live their lives.

The book develops this theory of "mapping politics" in relation to the empirical exploration of the politics of modern Italy. Italian politics is often seen as expressing either the timeless features of political culture (national or regional) whose origins lie in the primordial mists of the distant past or else the slow and agonized achievement of a national politics of individual preferences in the face of entrenched institutions and political practices committed to sustaining social and regional identities that work against national unity and common political purpose. Such perspectives are readily comparable to the political culture and rational actor theories mentioned previously. In their stead, and throughout this book, I propose a perspective that sees Italy's national space as being in historical flux, without presuming either fixed regional cultures or an emerging national politics of individual preferences.

Previous accounts have tended to see local geographical differences as representing the past either as inscribed in the contemporary political landscape or as residual to a present that is increasingly homogenized and nationalized. Alternatively, however, group membership is realized, identities are formed, and preferences are defined in shifting geographical settings, or places, that have different local and long-distance linkages over time. From this point of view geography is dynamic rather than static. It refers to the ways life processes impinge on politics as their local and long-distance components change over time rather than operating within fixed, permanent geographical parameters such as those set down by current national-state boundaries or historical regional designations. Much contemporary social science depends implicitly on the prior and unexamined valorization of geographical units of account (the state, the city, administrative regions) and thereby occludes the possibility of seeing politics (or other phenomena) as geographically dynamic.

WHY ITALY?

The focus on Italian politics might be seen as biasing the case in favor of the perspective of geographical dynamics. After all, Italy is usually seen as very unlike the rest of Europe or the industrial-capitalist world in general. It is notoriously divided geographically, socially, and politically.

Notwithstanding the limited appropriateness of a charge of bias, Italy does have a number of advantages as a focus for the general argument of the book. One is that Italian scholars have been intrigued by the differences between regions and localities within the country, from the

THEMES OF PLACE AND POLITICS

Four themes can be identified that cut across all chapters to provide the links between the empirical material on Italian politics and understandings of it (in chapters 3-9) and the theory of mapping politics (in chapter 2).

Place and Scale

The first theme concerns the way geographical differences are understood and interpreted. Rather than a "metric" space, divided into compact areas, place involves a conception of topological space in which diverse geographical scales are brought together through networks of internal (locale) and external (location) ties in defining geographical variation in social characteristics. People also invest meaning in the places they inhabit. The scales by which they identify themselves and their group memberships (national, local, international) vary both from country to country and over time. Since the nineteenth century in Europe the national scale has often been presumed as the scale for establishing primary political identity. But sense of place at the national scale can coexist with or be replaced by alternative ones. Existing geographical variation in a given phenome-non--party vote, geographical sense of political identity, and so forth-- responds to changes in the interaction of networks that interweave the internal and the external to produce new geographical variation in the same phenomenon over time.

In other words, geographical variation cannot simply be read off one geographical scale, and it changes over time as the balance of influences across scales changes. Place differences therefore are a necessary concomitant to the interrelation of social, economic, and political processes across scales that come together or are mediated through the cultural practices of existing settings. In this way geography is inherent in or constitutive of social processes rather than merely a backdrop on which they are inscribed.

Why has this sort of perspective rarely achieved much emphasis among social scientists or historians? For one thing, the concept of place became fatefully identified with that of community at the turn of the twentieth century when the current intellectual division of labor among social science disciplines was largely established. When community was viewed as in decline under the impact of industrialization and urbanization (and more recently the effects of new communication technologies such as cell phones and the Internet), place was eclipsed too. At the same time "society," rather than remaining solely an abstraction or ideal type, was defined in practical terms as coterminous with the national state. A single geographical scale--that of the national state--thus became the geographical base on which much social science was founded.

In addition, dominant representations of terrestrial space have followed the identity that grew up in the nineteenth century between abstraction and scientific validity. Geographical variation, multicausal explanations, local specificity, and vernacular understandings are all antithetical to the concept of space either as national chunks or as the result of structural relations (for example, in the core/periphery relations of subordination and incorporation of world systems and dependency theories). "Science" is about finding causal relations that either are independent of time and space or vary predictably across area types or between time periods. In fact what often happens is that uniformity is imposed by selecting taken-for-granted geographic units and holding numerous potential causal variables ceteris paribus (as if their effects were not present) so that universality can then be discovered.

The distinction between different geographical scales or levels has also been a problem because they have served to distinguish various areas of study (such as international relations versus domestic politics or micro-versus macroeconomics) and levels of generalization and causality (ecological versus individual inference) rather than complexly related dimensions of the contexts in which actual social and political processes occur. Integrating scales is difficult or even heretical when different fields determine their specialty by basing their uniqueness on different scales and when analysis (reducing explanation to the simplest level) has tended to win out over synthesis (putting together elements of explanation that emerge across a range of scales).

Finally, representations of space and how we think they figure in understanding politics or other social phenomena are not merely epis-temic--functions of how we just happen to think. They are closely related to the dominant political and material conditions of the eras when they are articulated. But they often live on after those eras have closed because of intellectual inertia and the closed character of the intellectual tribes that dominate different fields. Much contemporary social science is still steeped in the theories and representations of space of such nineteenth-century founding fathers as Marx, Durkheim, and Weber. Notwithstanding the legitimating quotation from Durkheim I offer at the beginning of the chapter, none of these luminaries had much to say to the enterprise of integrating scales of analysis into the concept of place. Yet the complexities of social life in a globalizing world require nothing less.

Historical Contingency

Since the late nineteenth century, Anglo-American political science has been trying to escape from the twin constraints of time and space by searching for empirical regularities that are independent of both. The goal has been to imitate an image of physics or mathematics as fields that made abstractions beyond the confines of the everyday and that were widely admired among academics for the causal simplicity, mathematical elegance, and aesthetic brilliance of their discoveries. Associated with this has been the drive to construct a state-centered applied social science that would better manage the various problems encountered during state formation.

REQUEST ACCESSIBLE FILE

If you are a student who cannot use this book in printed form, BiblioVault may be able to supply you with an electronic file for alternative access.

Please have the accessibility coordinator at your school fill out this form.

It can take 2-3 weeks for requests to be filled.

See other books on: Agnew, John A. | Italy | Modern Italy | Place | Political geography

See other titles from University of Chicago Press

Nearby on shelf for Political institutions and public administration (Europe) / Italy:

9780870137105

9780674534353