Though polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) have been banned in the United States for more than thirty years, the toxic effects of their presence in local environments continue to be a significant public health concern. PCBs: Human and Environmental Disposition and Toxicology brings together more than fifty established specialists on PCB toxicity to discuss recent trends and specialized investigations of PCB influences on the environment and on humans. Renowned scientists including Paul S. Cooke, Takeshi Nakano, Tomas Trnovec, Deborah C. Rice, Linda S. Birnbaum, and Charles S. Wong present cutting-edge research on Hudson River PCBs, human contamination, homologue profiles, high PCB exposure in Slovakia, and PCB effects on the thyroid hormone, nutrition, and estrogen levels in humans and animals. Focusing on the detection, movement, metabolism, toxicity, remediation, and risk assessment of PCB contamination, this multi-disciplinary study is a valuable resource for regulatory agencies and scientists working with PCBs.

With the goal of sketching “at least some of the bright lights and dark shadows of the war;” William Baxter authored his regional classic, Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove, in 1864, before the actual end of the Civil War.

Primarily focusing on the civilians of the region, Baxter vividly describes their precarious and vulnerable positions during the advances and retreats of armies as Confederate and Federal forces marched across their homeland. In his account, Baxter describes skirmishes and cavalry charges outside his front door, the “firing” of his town’s buildings during a Confederate retreat, clashes between secessionist and Unionist neighbors, the feeding of hungry soldiers and the forceful appropriation of his remaining food supply, and the sickening sight of the wounded emerging from the Prairie Grove battlefield.

Since its original printing, this firsthand account has only been reprinted once, in 1957, and both editions are considered collectors’ items today. Of interest to Civil War scholars and general readers alike, Baxter’s compelling social history is rendered even more comprehensive by William Shea’s introduction. Pea Ridge and Prairie Grove is a valuable personal account of the Civil War in the Trans-Mississippi West which enables us to better comprehend the conflict as a whole and its devastating effect on the general populace of the war-torn portions of the country.

It all began as a small frontier academy in 1785. The institution that would become Peabody experienced its first reinvention two decades later as it became Cumberland College, and then, in 1826, the University of Nashville. The University maintained an elite undergraduate college until 1850, and, despite the success of its medical school and a military institute, it failed in three subsequent efforts to restart its undergraduate program.

In 1875 the University offered its campus and degree-granting authority to the first normal school in the state of Tennessee, a school funded by the Peabody Education Fund. The Peabody Normal College was the best in the South, and, as such, exerted an enormous influence on education in the region.

A new era began in 1909. The trustees of the Peabody Fund, at its liquidation, provided an eventual $1.5 million to establish a graduate-level George Peabody College for Teachers. It opened for classes in 1914, on its present campus, where it quickly became the premier teachers' college in the South. As was the case with many private, independent institutions, Peabody faced intermittent financial struggles, which finally ended with its union with Vanderbilt. Today Peabody is, by almost any criteria, one of the five or six strongest colleges of education in the United States.

Addams's unyielding pacifism during the Great War drew criticism from politicians and patriots who deemed her the "most dangerous woman in America." Even those who had embraced her ideals of social reform condemned her outspoken opposition to U.S. entry into World War I or were ambivalent about her peace platforms. Turning away from the details of the war itself, Addams relies on memory and introspection in this autobiographical portrayal of efforts to secure peace during the Great War. "I found myself so increasingly reluctant to interpret the motives of other people that at length I confined all analysis of motives to my own," she writes. Using the narrative technique she described in The Long Road of Women's Memory, an extended musing on the roles of memory and myth in women's lives, Addams also recalls attacks by the press and defends her political ideals.

Katherine Joslin's introduction provides additional historical context to Addams's involvement with the Woman's Peace Party, the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, and her work on Herbert Hoover's campaign to provide relief and food to women and children in war-torn enemy countries.

One contributor, a longtime president of the American Council of Learned Societies, calls for "intellectual philanthropy" and suggests that academics should transcend their ideological differences and form cooperative partnerships in the public service. A pair of essays, by key figures of the 1989 Velvet Revolution in Eastern Europe, analyze the ways that self-confidence and self-regard undercut efforts toward the resolution of complex social problems. The qualities of ideological self-subversion and even weakness, Common Knowledge maintains, are essential if the intellectual community is to become an agent for peace in a time of war.

Contributors. Wayne Andersen, Sissela Bok, Yves Bonnefoy, Caroline Walker Bynum, Clare Cavanagh, Charles-Albert Cingria, Caryl Emerson, Clifford Geertz, Stanley N. Katz, Aileen Kelly, Adam Michnik, Péter Nádas, Eugene Ostashevsky, Jeffrey M. Perl, Marjorie Perloff, Nina Pelikan Straus, Rei Terada, Gianni Vattimo, William Vesterman, Aleksandr Vvedensky, Adam Zagajewski.

In September of 1963, Reverend Lawrence Roberts and the Angelic Choir of the First Baptist Church of Nutley, New Jersey, teamed with rising gospel star James Cleveland to record Peace Be Still. The LP and its haunting title track became a phenomenon. Robert M. Marovich draws on extensive oral interviews and archival research to chart the history of Peace Be Still and the people who created it. Emerging from an established gospel music milieu, Peace Be Still spent several years as the bestselling gospel album of all time. As such, it forged a template for live recordings of services that transformed the gospel music business and Black worship. Marovich also delves into the music's connection to fans and churchgoers, its enormous popularity then and now, and the influence of the Civil Rights Movement on the music's message and reception.

The first in-depth history of a foundational recording, Peace Be Still shines a spotlight on the people and times that created a gospel music touchstone.

Trends in the number and scope of peace operations since 2000 evidence heightened international appreciation for their value in crisis-response and regional stabilization. Peace Operations: Trends, Progress, and Prospects addresses national and institutional capacities to undertake such operations, by going beyond what is available in previously published literature.

Part one focuses on developments across regions and countries. It builds on data- gathering projects undertaken at Georgetown University's Center for Peace and Security Studies (CPASS), the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), and the Folke Bernadotte Academy (FBA) that offer new information about national contributions to operations and about the organizations through which they make those contributions. The information provides the bases for arriving at unique insights about the characteristics of contributors and about the division of labor between the United Nations and other international entities.

Part two looks to trends and prospects within regions and nations. Unlike other studies that focus only on regions with well-established track records—specifically Europe and Africa—this book also looks to the other major areas of the world and poses two questions concerning them: If little or nothing has been done institutionally in a region, why not? What should be expected?

This groundbreaking volume will help policymakers and academics understand better the regional and national factors shaping the prospects for peace operations into the next decade.

Growing numbers of people are displaced by war and violent conflict. In Ukraine, Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Myanmar, Syria, and elsewhere violence pushes civilian populations from their homes and sometimes from their countries, making them refugees. In previous decades, millions of refugees and displaced people returned to their place of origin after conflict or were resettled in countries in the Global North. Now displacements last longer, the number of people returning home is lower, and opportunities for resettlement are shrinking. More and more people spend decades in refugee camps or displaced within their own countries, raising their children away from their home communities and cultures. In this context, international policies encourage return to place of origin.

Using case studies and first-person accounts from interviews and fieldwork in post-conflict settings such as Uganda, Liberia, and Kosovo, Sandra F. Joireman highlights the divergence between these policies and the preferences of conflict-displaced people. Rather than looking from the top down, at the rights that people have in international and domestic law, the perspective of this text is from the ground up—examining individual and household choices after conflict. Some refugees want to go home, some do not want to return, some want to return to their countries of origin but live in a different place, and others are repatriated against their will when they have no other options. Peace, Preference, and Property suggests alternative policies that would provide greater choice for displaced people in terms of property restitution and solutions to displacement.

This intensively researched volume covers a previously neglected aspect of American history: the foreign policy perspective of the peace progressives, a bloc of dissenters in the U.S. Senate, between 1913 and 1935. The Peace Progressives and American Foreign Relations is the first full-length work to focus on these senators during the peak of their collective influence. Robert David Johnson shows that in formulating an anti-imperialist policy, the peace progressives advanced the left-wing alternative to the Wilsonian agenda.

The experience of World War I, and in particular Wilson’s postwar peace settlement, unified the group behind the idea that the United States should play an active world role as the champion of weaker states. Senators Asle Gronna of North Dakota, Robert La Follette and John Blaine of Wisconsin, and William Borah of Idaho, among others, argued that this anti-imperialist vision would reconcile American ideals not only with the country’s foreign policy obligations but also with American economic interests. In applying this ideology to both inter-American and European affairs, the peace progressives emerged as the most powerful opposition to the business-oriented internationalism of the decade’s Republican administrations, while formulating one of the most comprehensive critiques of American foreign policy ever to emerge from Congress.

Peacebuilding, Power, and Politics in Africa is a critical reflection on peacebuilding efforts in Africa. The authors expose the tensions and contradictions in different clusters of peacebuilding activities, including peace negotiations; statebuilding; security sector governance; and disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration. Essays also address the institutional framework for peacebuilding in Africa and the ideological underpinnings of key institutions, including the African Union, NEPAD, the African Development Bank, the Pan-African Ministers Conference for Public and Civil Service, the UN Peacebuilding Commission, the World Bank, and the International Criminal Court. The volume includes on-the-ground case study chapters on Sudan, the Great Lakes Region of Africa, Sierra Leone and Liberia, the Niger Delta, Southern Africa, and Somalia, analyzing how peacebuilding operates in particular African contexts.

The authors adopt a variety of approaches, but they share a conviction that peacebuilding in Africa is not a script that is authored solely in Western capitals and in the corridors of the United Nations. Rather, the writers in this volume focus on the interaction between local and global ideas and practices in the reconstitution of authority and livelihoods after conflict. The book systematically showcases the tensions that occur within and between the many actors involved in the peacebuilding industry, as well as their intended beneficiaries. It looks at the multiple ways in which peacebuilding ideas and initiatives are reinforced, questioned, reappropriated, and redesigned by different African actors.

A joint project between the Centre for Conflict Resolution in Cape Town, South Africa, and the Centre of African Studies at the University of Cambridge.

With A Peaceful Conquest, Cara Lea Burnidge presents the most detailed analysis yet of how Wilson’s religious beliefs affected his vision of American foreign policy, with repercussions that lasted into the Cold War and beyond. Framing Wilson’s intellectual development in relationship to the national religious landscape, and paying greater attention to the role of religion than in previous scholarship, Burnidge shows how Wilson’s blend of Southern evangelicalism and social Christianity became a central part of how America saw itself in the world, influencing seemingly secular policy decisions in subtle, lasting ways. Ultimately, Burnidge makes a case for Wilson’s religiosity as one of the key drivers of the emergence of the public conception of America’s unique, indispensable role in international relations.

As the presidential election cycle once again raises questions of America’s place in the world, A Peaceful Conquest offers a fascinating excavation of its little-known roots.

This book tells the remarkable story of Birzeit University, Palestine’s oldest university in the Occupied Territories.

Founded against the backdrop of occupation, it is open to all students, irrespective of income. Putting the study of democracy and tolerance at the heart of its curriculum, Birzeit continues to produce idealistic young people who can work to bring about a peaceful future. Gabi Baramki explains how the University has survived against shocking odds, including direct attacks where Israeli soldiers have shot unarmed students. Baramki himself has been dragged from his home at night, beaten and arrested. Yet Birzeit continues to thrive, putting peace at the heart of its teaching, and offering Palestinians the opportunities that only education can bring.

Although Americans claim to revere the Constitution, relatively few understand its workings. Its real importance for the average citizen is as an enduring reminder of the moral vision that shaped the nation's founding. Yet scholars have paid little attention to the broader appeal that constitutional idealism has always made to the American imagination through publications and films. Maxwell Bloomfield draws upon such neglected sources to illustrate the way in which media coverage contributes to major constitutional change.

Successive generations have sought to reaffirm a sense of national identity and purpose by appealing to constitutional norms, defined on an official level by law and government. Public support, however, may depend more on messages delivered by the popular media. Muckraking novels, such as Upton Sinclair's The Jungle (1906), debated federal economic regulation. Woman suffrage organizations produced films to counteract the harmful gender stereotypes of early comedies. Arguments over the enforcement of black civil rights in the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy v. Ferguson took on new meaning when dramatized in popular novels.

From the founding to the present, Americans have been taught that even radical changes may be achieved through orderly constitutional procedures. How both elite and marginalized groups in American society reaffirmed and communicated this faith in the first three decades of the twentieth century is the central theme of this book.

Does biology condemn the human species to violence and war? Previous studies of animal behavior incline us to answer yes, but the message of this book is considerably more optimistic. Without denying our heritage of aggressive behavior, Frans de Waal describes powerful checks and balances in the makeup of our closest animal relatives, and in so doing he shows that to humans making peace is as natural as making war.

In this meticulously researched and absorbing account, we learn in detail how different types of simians cope with aggression, and how they make peace after fights. Chimpanzees, for instance, reconcile with a hug and a kiss, whereas rhesus monkeys groom the fur of former adversaries. By objectively examining the dynamics of primate social interactions, de Waal makes a convincing case that confrontation should not be viewed as a barrier to sociality but rather as an unavoidable element upon which social relationships can be built and strengthened through reconciliation.

The author examines five different species—chimpanzees, rhesus monkeys, stump-tailed monkeys, bonobos, and humans—and relates anecdotes, culled from exhaustive observations, that convey the intricacies and refinements of simian behavior. Each species utilizes its own unique peacemaking strategies. The bonobo, for example, is little known to science, and even less to the general public, but this rare ape maintains peace by means of sexual behavior divorced from reproductive functions; sex occurs in all possible combinations and positions whenever social tensions need to be resolved. “Make love, not war” could be the bonobo slogan.

De Waal’s demonstration of reconciliation in both monkeys and apes strongly supports his thesis that forgiveness and peacemaking are widespread among nonhuman primates—an aspect of primate societies that should stimulate much needed work on human conflict resolution.

The bird itself, as Christine E. Jackson notes in Peacock, appears to enjoy its audience, preening and strutting about within a few feet of humans. It is not surprising, then, that these vain birds and their distinctive feathers have been the prized possessions of kings for nearly three thousand years. Jackson here explores the peacock’s beauty—and its apparent attitude—through fairy tales, fables, and superstitions in both Eastern and Western cultures. Peacock takes stock of the bird as it appears within art, from the earliest mosaics to medieval illuminated manuscripts to modern graphics, with a special emphasis on the peacock’s symbolic value in the nineteenth-century arts and crafts and art nouveau movements. Jackson further details the peacock’s colorful presence in hats, clothing, and even sports equipment.

A sweeping combination of social and natural history, Peacock is the first book to bring together all the shimmering, colorful facets of these magnificent birds.

In this first-ever ethnography of American gay suburbanites, Wayne H. Brekhus demonstrates that who one is depends at least in part on where and when one is. For many urban gay men, being homosexual is key to their identity because they live, work, and socialize in almost exclusively gay circles. Brekhus calls such men "lifestylers" or peacocks. Chameleons or "commuters," on the other hand, live and work in conventional suburban settings, but lead intense gay social and sexual lives outside the suburbs. Centaurs, meanwhile, or "integrators," mix typical suburban jobs and homes with low-key gay social and sexual activities. In other words, lifestylers see homosexuality as something you are, commuters as something you do, and integrators as part of yourself.

Ultimately, Brekhus shows that lifestyling, commuting, and integrating embody competing identity strategies that occur not only among gay men but across a broad range of social categories. What results, then, is an innovative work that will interest sociologists, psychologists, anthropologists, and students of gay culture.

The post-Cold War era has been difficult for Japan. A country once heralded for evolving a superior form of capitalism and seemingly ready to surpass the United States as the world’s largest economy lost its way in the early 1990s. The bursting of the bubble in 1991 ushered in a period of political and economic uncertainty that has lasted for over two decades. There were hopes that the triple catastrophe of March 11, 2011—a massive earthquake, tsunami, and accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant—would break Japan out of its torpor and spur the country to embrace change that would restart the growth and optimism of the go-go years. But several years later, Japan is still waiting for needed transformation, and Brad Glosserman concludes that the fact that even disaster has not spurred radical enough reform reveals something about Japan's political system and Japanese society. Glosserman explains why Japan has not and will not change, concluding that Japanese horizons are shrinking and that the Japanese public has given up the bold ambitions of previous generations and its current leadership. This is a critical insight into contemporary Japan and one that should shape our thinking about this vital country.

In Peak Oil, Matthew Schneider-Mayerson takes readers deep inside the world of “peakists,” showing how their hopes and fears about the postcarbon future led them to prepare for the social breakdown they foresee—all of which are fervently discussed and debated via websites, online forums, videos, and novels. By exploring the worldview of peakists, and the unexpected way that the fear of peak oil and climate change transformed many members of this left-leaning group into survivalists, Schneider-Mayerson builds a larger analysis of the rise of libertarianism, the role of oil in modern life, the political impact of digital technologies, the racial and gender dynamics of post-apocalyptic fantasies, and the social organization of environmental denial.

This book is a beautifully illustrated account of pearls through millennia, from fossils to contemporary jewelry. Pearls are the most human of gems, both miraculous and familiar. Uniquely organic in origin, they are as intimate as our bodies, created through the same process as we grow bones and teeth. They have long been described as an animal’s sacrifice, but until recently their retrieval often entailed the sacrifices of enslaved and indentured divers and laborers. While the shimmer of the pearl has enticed Roman noblewomen, Mughal princes, Hollywood royalty, mavericks, and renegades, encoded in its surface is a history of human endeavor, abuse, and aspiration—pain locked in the layers of a gleaming gem.

Pearls, People, and Power is the first book to examine the trade, distribution, production, and consumption of pearls and mother-of-pearl in the global Indian Ocean over more than five centuries. While scholars have long recognized the importance of pearling to the social, cultural, and economic practices of both coastal and inland areas, the overwhelming majority have confined themselves to highly localized or at best regional studies of the pearl trade. By contrast, this book stresses how pearling and the exchange in pearl shell were interconnected processes that brought the ports, islands, and coasts into close relation with one another, creating dense networks of connectivity that were not necessarily circumscribed by local, regional, or indeed national frames.

Essays from a variety of disciplines address the role of slaves and indentured workers in maritime labor arrangements, systems of bondage and transoceanic migration, the impact of European imperialism on regional and local communities, commodity flows and networks of exchange, and patterns of marine resource exploitation between the Industrial Revolution and Great Depression. By encompassing the geographical, cultural, and thematic diversity of Indian Ocean pearling, Pearls, People, and Power deepens our appreciation of the underlying historical dynamics of the many worlds of the Indian Ocean.

Contributors: Robert Carter, William G. Clarence-Smith, Joseph Christensen, Matthew S. Hopper, Pedro Machado, Julia T. Martínez, Michael McCarthy, Jonathan Miran, Steve Mullins, Karl Neuenfeldt, Samuel M. Ostroff, and James Francis Warren.

This book brings together the research into regional development and social change carried out in highland Peru by a team of British and Latin American social anthropologists and sociologists. The area studied—the Mantaro Valley of central Peru—is one of the most densely populated and economically differentiated of highland zones; it is also notable for its community-based forms of cooperation and its high level of peasant political activity.

The book presents a series of case studies that examine cooperative forms of organization in relation to developments in the regional economy and to changes in national policy. The analysis attempts to avoid interpreting local processes merely as responses to externally initiated change. It stresses instead the need to consider the interplay of local and national forces, because local groups and processes themselves affect the pattern of regional and national development. The case studies cover a range of political and economic topics, from peasant movements to the achievements and shortcomings of government-sponsored agricultural and manufacturing cooperatives. The concluding chapter, by the editors, explores the theoretical implications of these studies.

Professor Dorson traces the historical development of folklore as a field of learning, beginning with sixteenth-century antiquarians whose studies encompassed the preservation of local customs and reaching its climax with the "Great Team" of Andrew Lang and his co-workers from the 1870's to the First World War.

Scholars who study peasant society now realize that peasants are not passive, but quite capable of acting in their own interests. But, do coherent political ideas emerge within peasant society or do peasants act in a world where elites define political issues? Peasant Intellectuals is based on ethnographic research begun in 1966 and includes interviews with hundreds of people from all levels of Tanzanian society. Steven Feierman provides the history of the struggles to define the most basic issues of public political discourse in the Shambaa-speaking region of Tanzania. Feierman also shows that peasant society contains a rich body of alternative sources of political language from which future debates will be shaped.

The medieval peasantry represents a particularly compelling unknown for historians, as it holds the key to understanding both later economic growth and the surprising stagnation experienced in some European regions. Our current knowledge about the social structures and institutions of the medieval peasantry remains superficial, with almost nothing known about their real inner dynamics and demographic aspects. The present monograph confronts this issue head-on, taking advantage of previously neglected written sources from the Cheb city-state, which are unique in the European context. Drawing from this material, the book presents a remarkably detailed view of social mobility, migration, and the reproduction of social structures among the peasantry in the late Middle Ages while offering new perspectives on the mass abandonment of rural settlements during that period. It also identifies hitherto unknown mechanisms by which peasant communities responded to family demographic cycles and short-term economic fluctuations.

“The modern European state has lived upon a reservoir of soldiers and electors provided by the peasantry, but the peasants have remained the object of politics and not its master,” states Suzanne Berger. One of the few political scientists and students of the modernization process to look at the peasant-state relationship in the old nations of Europe, Berger explores the impact of mass organization on the politics of the peasants.

“One might have predicted,” she writes, “that as peasants became involved in local cooperative and syndical associations, their participation in the politics of the national community would have increased.” The results of her research show, however, that between 1911 and 1967 peasant participation in a wide range of rural associations did not significantly contribute to their integration into the national political system. Why have changes in rural society had so little impact on the peasant's political role?

In considering this question, the author compares peasant organizations in Finistere and Côtes-du-Nord, two backward agricultural departments in western France. Although the social and economic structures of these areas were essentially the same, different types of organizations mobilized the peasants. In Finistere, corporative associations separated the countryside from the currents of national political life. As a result, party politics in Finistere became stagnant, and peasant electors voted in 1967 as they had in the first quarter of the century. In Côtes-du-Nord, on the other hand, the forces that organized the peasants were political parties, and they involved the countryside in national politics. It is this involvement that, according to the author, has contributed to a politicization of local communities and resulted in radical political change.

Focusing on peasant struggles for market control over coffee exports in Bugisu from colonial times through the reign and overthrow of Idi Amin, Bunker shows that these freeholding peasants acted collectively and used the state's dependence on coffee export revenues to effectively influence and veto government programs inimical to their interests.

Bunker's work vividly portrays the small victories and great trials of ordinary people struggling to control their own economic destiny while resisting the power of the world economy.

Drawing on testimonies from contra collaborators and ex-combatants, as well as pro-Sandinista peasants, this book presents a dynamic account of the growing divisions between peasants from the area of Quilalí who took up arms in defense of revolutionary programs and ideals such as land reform and equality and those who opposed the FSLN.

Peasants in Arms details the role of local elites in organizing the first anti-Sandinista uprising in 1980 and their subsequent rise to positions of field command in the contras. Lynn Horton explores the internal factors that led a majority of peasants to turn against the revolution and the ways in which the military draft, and family and community pressures reinforced conflict and undermined mid-decade FSLN policy shifts that attempted to win back peasant support.

Based on extended interviews at the Culiprán fundo in Chile with peasants who recount in their own terms their political evolution, this is an in-depth study of peasants in social and political action. It deals with two basic themes: first, the authoritarian structure within a traditional latifundio and its eventual replacement by a peasant-based elected committee, and second, the events shaping the emergence of political consciousness among the peasantry. Petras and Zemelman Merino trace the careers of local peasant leaders, followers, and opponents of the violent illegal land seizure in 1965 and the events that triggered the particular action.

The findings of this study challenge the oft-accepted assumption that peasants represent a passive, traditional, downtrodden group capable only of following urban-based elites. The peasant militants, while differing considerably in their ability to grasp complex political and social problems, show a great deal of political skill, calculate rationally on the possibility of success, and select and manipulate political allies on the basis of their own primary needs. The politicized peasantry lend their allegiance to those forces with whom they anticipate they have the most to gain—and under circumstances that minimize social costs. The authors identify the highly repressive political culture within the latifundio—reinforced by the national political system—as the key factor inhibiting overt expressions of political demands.

The emergence of revolutionary political consciousness is found to be the result of cumulative experiences and the breakdown of traditional institutions of control. The violent illegal seizure of the farm is perceived by the peasantry as a legitimate act based on self-interest as well as general principles of justice—in other words, the seizure is perceived as a “natural act,” suggesting that perhaps two sets of moralities functioned within the traditional system.

The book is divided into two parts: the first part contains a detailed analysis of peasant behavior; the second contains transcriptions of peasant interviews. Combined, they give the texture and flavor of insurgent peasant politics.

"total history" when it was published in France in 1966, Le Roy Ladurie's

volume combines elements of human geography, historical demography, economic

history, and folk culture in a broad depiction of a great agrarian cycle,

lasting from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. It describes the conflicts

and contradictions of a traditional peasant society in which the rise in

population was not matched by increases in wealth and food production.

"It presents us with a great study of rural history, an analysis of economic change and a description of a society

in movement that has few equals."

-- Washington Post Book World

"It is without any doubt one of the most important, if not the most important, monograph of the French Annales school of socio-economic

historians written in the last decade." -- Canadian Historical Review

Grounded in the theoretical perspectives of subaltern studies and drawing on an extremely complete archive of landed estates that includes detailed regular reports by plantation managers on all aspects of farming life, Peasants on Plantations reveals the intricate ways peasants, managers, and owners manipulated each other to benefit their own interests. As Peloso demonstrates, rather than a simple case of domination of the peasants by the owners, both parties realized that negotiation was the key to successful growth, often with the result that peasants cooperated with plantation growth strategies in order to participate in a market economy. Long-term contracts gave tenants and sharecroppers many opportunities to make farming choices, to assert claims on the land, compete among themselves, and participate in plantation expansion. At the same time, owners strove to keep the peasants in debt and well aware of who maintained ultimate control.

Peasants on Plantations offers a largely untold view of the monumental struggle between planters and peasants that was fundamental in shaping the agrarian history of Peru. It will interest those engaged in Latin American studies, anthropology, and peasant and agrarian studies.

Throughout Latin America and the rest of the Third World, profound social problems are growing in response to burgeoning populations and unstable economic and political systems. In Peru, terrorist acts by the Shining Path guerilla movement are the most visible manifestation of social discontent, but rapid economic and religious changes have touched the lives of almost everyone, radically altering traditional lifeways. In this twenty-year study of the community of Quinua in the Department of Ayacucho, William Mitchell looks at changes provoked by population growth within a severely limited ecological and economic setting, including increasing conversion to a cash economy and out-migration, the decline of the Catholic fiesta system and the rise of Protestantism, and growing poverty and revolution.

When Mitchell first began his field studies in Quinua in 1966, farming was still the Quinueños' principal means of livelihood. But while the population was increasing rapidly, the amount of arable land in the community remained the same, creating increased food shortfalls. At the same time, government controls on food prices and subsidies of cheap food imports drove down the value of rural farm production. These ecological and economic factors forced many people to enter the nonfarm economy to feed themselves.

Using a materialist approach, Mitchell charts the new economic strategies that Quinueños use to confront the harsh pressures of their lives, including ceramic production, wage labor, petty commerce, and migration to cash work on the coat and in the eastern tropical forests. In addition, he shows how the growing conversion from Catholicism to Protestantism is also an economic strategy, since Protestant ideology offers acceptable reasons for redirecting the money that used to be spent on elaborate religious festivals to household needs and education.

The twenty-year span of this study makes it especially valuable for students of social change. Mitchell's unique, interdisciplinary approach, considering ecological, economic, and population factors simultaneously, offers a model that can be widely applied in many Third World areas. Additionally, the inclusion of an entire chapter of family histories reveals how economic and ecological forces are played out at the individual level.

Supported by the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, Collegeof Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame

What would Thanksgiving be without pecan pie? New Orleans without pecan pralines? Southern cooks would have to hang up their aprons without America’s native nut, whose popularity has spread far beyond the tree’s natural home. But as familiar as the pecan is, most people don’t know the fascinating story of how native pecan trees fed Americans for thousands of years until the nut was “improved” a little more than a century ago—and why that rapid domestication actually threatens the pecan’s long-term future.

In The Pecan, acclaimed writer and historian James McWilliams explores the history of America’s most important commercial nut. He describes how essential the pecan was for Native Americans—by some calculations, an average pecan harvest had the food value of nearly 150,000 bison. McWilliams explains that, because of its natural edibility, abundance, and ease of harvesting, the pecan was left in its natural state longer than any other commercial fruit or nut crop in America. Yet once the process of “improvement” began, it took less than a century for the pecan to be almost totally domesticated. Today, more than 300 million pounds of pecans are produced every year in the United States—and as much as half of that total might be exported to China, which has fallen in love with America’s native nut. McWilliams also warns that, as ubiquitous as the pecan has become, it is vulnerable to a “perfect storm” of economic threats and ecological disasters that could wipe it out within a generation. This lively history suggests why the pecan deserves to be recognized as a true American heirloom.

From the first written record of it made by the Spaniard Cabeza de Vaca in 1528 to its nineteenth-century domestication and its current development into a multimillion dollar crop, the pecan tree has been broadly appreciated for its nutritious nuts and its beautiful wood. In Pecan: America’s Native Nut Tree, Lenny Wells explores the rich and fascinating story of one of North America’s few native crops, long an iconic staple of southern foods and landscapes.

Fueled largely by a booming international interest in the pecan, new discoveries about the remarkable health benefits of the nut, and a renewed enthusiasm for the crop in the United States, the pecan is currently experiencing a renaissance with the revitalization of America’s pecan industry. The crop’s transformation into a vital component of the US agricultural economy has taken many surprising and serendipitous twists along the way. Following the ravages of cotton farming, the pecan tree and its orchard ecosystem helped to heal the rural southern landscape. Today, pecan production offers a unique form of agriculture that can enhance biodiversity and protect the soil in a sustainable and productive manner.

Among the many colorful anecdotes that make the book fascinating reading are the story of André Pénicaut’s introduction of the pecan to Europe, the development of a Latin name based on historical descriptions of the same plant over time, the use of explosives in planting orchard trees, the accidental discovery of zinc as an important micronutrient, and the birth of “kudzu clubs” in the 1940s promoting the weed as a cover crop in pecan orchards.

**Published in cooperation with the Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation, Ellis Brothers Pecan, Inc., and The Mason Pecans Group**

This is a true story of the struggle, survival, and ultimate success of a large black family in south Alabama who, in the middle decades of the 20th century, lifted themselves out of poverty to achieve the American dream of property ownership. Descended from slaves and sharecroppers in the Black Belt region, this family of hard-working parents and their thirteen children is mentored by its matriarch, Moa, the author’s beloved great grandmother, who passes on to the family, along with other cultural wealth, her recipe for moonshine.

Without rancor or blame, and even with occasional humor, The Pecan Orchard offers a window into the inequities between blacks and whites in a small southern town still emerging from Jim Crow attitudes.

Told in clean, straightforward prose, the story radiates the suffocating midday heat of summertime cotton fields and the biting winter wind sifting through porous shanty walls. It conveys the implicit shame in “Colored Only” restrooms, drinking fountains, and eating areas; the beaming satisfaction of a job well done recognized by others; the “yessum” manners required of southern society; and the joyful moments, shared memories, and loving bonds that sustain—and even raise—a proud family.

A trenchant case for a novel philosophical position: that our political thinking is driven less by commitments to freedom or fairness than by an aversion to hierarchy.

Niko Kolodny argues that, to a far greater extent than we recognize, our political thinking is driven by a concern to avoid relations of inferiority. In order to make sense of the most familiar ideas in our political thought and discourse—the justification of the state, democracy, and rule of law, as well as objections to paternalism and corruption—we cannot merely appeal to freedom, as libertarians do, or to distributive fairness, as liberals do. We must instead appeal directly to claims against inferiority—to the conviction that no one should stand above or below.

The problem of justifying the state, for example, is often billed as the problem of reconciling the state with the freedom of the individual. Yet, Kolodny argues, once we press hard enough on worries about the state’s encroachment on the individual, we end up in opposition not to unfreedom but to social hierarchy. To make his case, Kolodny takes inspiration from two recent trends in philosophical thought: on the one hand, the revival of the republican and Kantian traditions, with their focus on domination and dependence; on the other, relational egalitarianism, with its focus on the effects of the distribution of income and wealth on our social relations.

The Pecking Order offers a detailed account of relations of inferiority in terms of objectionable asymmetries of power, authority, and regard. Breaking new ground, Kolodny looks ahead to specific kinds of democratic institutions that could safeguard against such relations.

Peckinpah: The Western Films first appeared in 1980, when the director's reputation was at low ebb. The book helped lead a generation of readers and filmgoers to a full and enduring appreciation of Peckinpah's landmark films, locating his work in the central tradition of American art that goes all the way back to Emerson, Hawthorne, and Melville. In addition to a new section on the personal significance of The Wild Bunch to Peckinpah, Seydor has added to this expanded, revised edition a complete account of the successful, but troubled, efforts to get a fully authorized director's cut released. He describes how an initial NC-17 rating of the film by the Motion Picture Association of America's ratings board nearly aborted the entire project. He also adds a great wealth of newly discovered biographical detail that has surfaced since the director's death and includes a new chapter on Noon Wine, credited with bringing Peckinpah's television work to a fitting resolution and preparing his way for The Wild Bunch.

This edition stands alone in offering full treatment of all versions of Peckinpah's Westerns. It also includes discussion of all fourteen episodes of Peckinpah's television series, The Westerner, and a full description of the versions of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid now (or formerly) in circulation, including an argument that the label "director's cut" on the version in release by Turner is misleading. Additionally, the book's final chapter has been substantially rewritten and now includes new information about Peckinpah's background and sources.

Written exclusively for this collection by today’s leading Peckinpah critics, the nine essays in Peckinpah Today explore the body of work of one of America’s most important filmmakers, revealing new insights into his artistic process and the development of his lasting themes. Edited by Michael Bliss, this book provides groundbreaking criticism of Peckinpah’s work by illuminating new sources, from modified screenplay documents to interviews with screenplay writers and editors.

Included is a rare interview with A. S. Fleischman, author of the screenplay for The Deadly Companions, the film that launched Peckinpah’s career in feature films. The collection also contains essays by scholar Stephen Prince and Paul Seydor, editor of the controversial special edition of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. In his essay on Straw Dogs, film critic Michael Sragow reveals how Peckinpah and co-scriptwriter David Zelag Goodman transformed a pulp novel into a powerful film. The final essay of the collection surveys Peckinpah’s career, showing the dark turn that the filmmaker’s artistic path took between his first and last films. This comprehensive approach reinforces the book’s dawn-to-dusk approach, resulting in a fascinating picture of a great filmmaker’s work.

Alfred V. Kidder’s excavations at Pecos Pueblo in New Mexico between 1914 and 1929 set a new standard for archaeological fieldwork and interpretation. Among his other innovations, Kidder recognized that skeletal remains were a valuable source of information, and today the Pecos sample is used in comparative studies of fossil hominins and recent populations alike.

In the 1990s, while documenting this historic collection in accordance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act before the remains were returned to the Pueblo of Jemez and reinterred at Pecos Pueblo, Michèle E. Morgan and colleagues undertook a painstaking review of the field data to create a vastly improved database. The Peabody Museum, where the remains had been housed since the 1920s, also invited a team of experts to collaboratively study some of the materials.

In Pecos Pueblo Revisited, these scholars review some of the most significant findings from Pecos Pueblo in the context of current Southwestern archaeological and osteological perspectives and provide new interpretations of the behavior and biology of the inhabitants of the pueblo. The volume also presents improved data sets in extensive appendices that make the primary data available for future analysis. The volume answers many existing questions about the population of Pecos and other Rio Grande sites and will stimulate future analysis of this important collection.

A Peculiar Imbalance is the little-known history of the black experience in Minnesota in the mid-1800s, a time of dramatic change in the region. William D. Green explains how, as white progressive politicians pushed for statehood, black men who had been integrated members of the community, owning businesses and maintaining good relationships with their neighbors, found themselves denied the right to vote or to run for office in those same communities.

As Minnesota was transformed from a wilderness territory to a state, the concepts of race and ethnicity and the distinctions among them made by Anglo-Americans grew more rigid and arbitrary. A black man might enjoy economic success and a middle-class lifestyle but was not considered a citizen under the law. In contrast, an Irish Catholic man was able to vote—as could a mixed-blood Indian—but might find himself struggling to build a business because of the ethnic and religious prejudices of the Anglo-American community. A Peculiar Imbalance examines these disparities, reflecting on the political, social, and legal experiences of black men from 1837 to 1869, the year of black suffrage.

The U.S. death penalty is a peculiar institution, and a uniquely American one. Despite its comprehensive abolition elsewhere in the Western world, capital punishment continues in dozens of American states– a fact that is frequently discussed but rarely understood. The same puzzlement surrounds the peculiar form that American capital punishment now takes, with its uneven application, its seemingly endless delays, and the uncertainty of its ever being carried out in individual cases, none of which seem conducive to effective crime control or criminal justice. In a brilliantly provocative study, David Garland explains this tenacity and shows how death penalty practice has come to bear the distinctive hallmarks of America’s political institutions and cultural conflicts.

America’s radical federalism and local democracy, as well as its legacy of violence and racism, account for our divergence from the rest of the West. Whereas the elites of other nations were able to impose nationwide abolition from above despite public objections, American elites are unable– and unwilling– to end a punishment that has the support of local majorities and a storied place in popular culture.

In the course of hundreds of decisions, federal courts sought to rationalize and civilize an institution that too often resembled a lynching, producing layers of legal process but also delays and reversals. Yet the Supreme Court insists that the issue is to be decided by local political actors and public opinion. So the death penalty continues to respond to popular will, enhancing the power of criminal justice professionals, providing drama for the media, and bringing pleasure to a public audience who consumes its chilling tales.

Garland brings a new clarity to our understanding of this peculiar institution– and a new challenge to supporters and opponents alike.

Sunday observance in the Christian West was an important religious issue from late Antiquity until at least the early twentieth century. In England the subject was debated in Parliament for six centuries. During the reign of Charles I disagreements about Sunday observance were a factor in the Puritan flight from England. In America the Sunday question loomed large in the nation’s newspapers. In the nineteenth century, it was the lengthiest of our national debates—outlasting those of temperance and slavery. In a more secular age, many writers have been haunted by the afterlife of Sunday. Wallace Stevens speaks of the “peculiar life of Sundays.” For Kris Kristofferson “there’s something in a Sunday, / Makes a body feel alone.”

From Augustine to Caesarius, through the Reformation and the Puritan flight from England, down through the ages to contemporary debates about Sunday worship, Stephen Miller explores the fascinating history of the Sabbath. He pays particular attention to the Sunday lives of a number of prominent British and American writers—and what they have had to say about Sunday. Miller examines such observant Christians as George Herbert, Samuel Johnson, Edmund Burke, Hannah More, and Jonathan Edwards. He also looks at the Sunday lives of non-practicing Christians, including Oliver Goldsmith, Joshua Reynolds, John Ruskin, and Robert Lowell, as well as a group of lapsed Christians, among them Edmund Gosse, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Thoreau, and Wallace Stevens. Finally, he examines Walt Whitman’s complex relationship to Christianity. The result is a compelling study of the changing role of religion in Western culture.

A Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon 1788–1940 remains the most comprehensive chronology of Black life in Oregon more than forty years after its original publication in 1980. The book has long been a resource for those seeking information on the legal and social barriers faced by people of African descent in Oregon. Elizabeth McLagan’s work reveals how in spite of those barriers, Black individuals and families made Oregon their home, and helped create the state’s modern Black communities. Long out of print, the book is available again through this co-publication with Oregon Black Pioneers, Oregon’s statewide African American historical society. The revised second edition includes additional details for students and scholars, an expanded reading list, a new selection of historic images, and a new foreword by Gwen Carr and an afterword by Elizabeth McLagan.

A Peculiar People explores the origin and growth of the Old Order Amish in Iowa, their religious practices, economic organization, family life, the formation of new communities, and the vital issue of education. Included also are appendixes giving the 1967 “Act Relating to Compulsory School Attendance and Educational Standards”; a sample “Church Organization Financial Agreement,” demonstrating the group’s unusual but advantageous mutual financial system; and the 1632 Dortrecht Confession of Faith, whose eighteen articles cover all the basic religious tenets of the Old Order Amish.

Thomas Morain’s new essay describes external and internal issues for the Iowa Amish from the 1970s to today. The growth of utopian Amish communities across the nation, changes in occupation (although The Amish Directory still lists buggy shop operators, wheelwrights, and one lone horse dentist), the current state of education and health care, and the conscious balance between modern and traditional ways are reflected in an essay that describes how the Old Order dedication to Gelassenheit—the yielding of self to the interests of the larger community—has served its members well into the twenty-first century.

Sensationalized accounts of white rural communities’ aberrant sexualities, racial intermingling, gender transgressions, and anomalous bodies and minds, which proliferated from the turn of the century, created a national view of the perversity of white rural poverty for the American public. Cartwright contends that these accounts, extracted and estranged from their own ambivalent forum of community gossip, must be read in kind: through a racialized, materialist queercrip optic of the deeply familiar and mundane. Taking in popular science, documentary photography, news media, documentaries, and horror films, Peculiar Places orients itself at the intersections of disability studies, queer studies, and gender studies to illuminate a racialized landscape both profoundly ordinary and familiar.

In a time when Mormons appear to have larger roles in everything from political conflict to television shows and when Mormon-related topics seem to show up more frequently in the news, eight scholars take a close look at Mormonism in popular media: film, television, theater, and books.

Some contributors examine specific works, including the Tony-winning play Angels in America, the hit TV series Big Love, and the bestselling books Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith and The Miracle Life of Edgar Mint. Others consider the phenomena of Mormon cinema and Mormon fiction; the use of the Mormon missionary as a stock character in films; and the noticeably prominent presence of Mormons in reality television shows.

On October 3, 1968, a military junta led by General Juan Velasco Alvarado took over the government of Peru. In striking contrast to the right-wing, pro–United States/anti-Communist military dictatorships of that era, however, Velasco’s “Revolutionary Government of the Armed Forces” set in motion a left-leaning nationalist project aimed at radically transforming Peruvian society by eliminating social injustice, breaking the cycle of foreign domination, redistributing land and wealth, and placing the destiny of Peruvians into their own hands. Although short-lived, the Velasco regime did indeed have a transformative effect on Peru, the meaning and legacy of which are still subjects of intense debate.

The Peculiar Revolution revisits this fascinating and idiosyncratic period of Latin American history. The book is organized into three sections that examine the era’s cultural politics, including not just developments directed by the Velasco regime but also those that it engendered but did not necessarily control; its specific policies and key institutions; and the local and regional dimensions of the social reforms it promoted. In a series of innovative chapters written by both prominent and rising historians, this volume illuminates the cultural dimensions of the revolutionary project and its legacies, the impact of structural reforms at the local level (including previously understudied areas of the country such as Piura, Chimbote, and the Amazonia), and the effects of state policies on ordinary citizens and labor and peasant organizations.

Pedagogical Innovations in Oral Academic Communication is grounded in four key principles: academic discourse socialization; context-responsive instruction; instructional approaches of English for Academic Purposes and English for Specific Purposes; and asset-oriented pedagogy. In the chapters in this collection, the authors share their teaching context, the details and underlying principles of their pedagogical approach, and recommendations for practitioners. Readers will develop a deeper understanding of the communicative contexts their students inhabit, including the types of speaking situations they are likely to encounter, and understand how to innovate their approach to teaching oral communication to students from diverse cultural, linguistic, educational, and disciplinary backgrounds. Such innovations prepare students for more effective communication during their academic studies and professional career, a goal that is of central importance in our globally interconnected society.

In these meditations, Alexander deftly unites large, often contradictory, historical processes across time and space. She focuses on the criminalization of queer communities in both the United States and the Caribbean in ways that prompt us to rethink how modernity invents its own traditions; she juxtaposes the political organizing and consciousness of women workers in global factories in Mexico, the Caribbean, and Canada with the pressing need for those in the academic factory to teach for social justice; she reflects on the limits and failures of liberal pluralism; and she presents original and compelling arguments that show how and why transgenerational memory is an indispensable spiritual practice within differently constituted women-of-color communities as it operates as a powerful antidote to oppression. In this multifaceted, visionary book, Alexander maps the terrain of alternative histories and offers new forms of knowledge with which to mold alternative futures.

The contributors describe ways of building communities within and beyond academic programs and examine what it means to engage in community-building work and action across institutional boundaries. In Part One, the essayists focus on the centrality of community building and reinterpreting bodies of knowledge with students, staff, faculty, and community members. Part Two looks at bringing transnational approaches to feminist collaborations in ways that challenge the classroom’s central place in knowledge production. Part Three explores organic collaborations in and beyond the classroom.

A practical and much-needed resource, Pedagogies of Interconnectedness offers cutting-edge ideas for collaboration in pedagogy, education justice, community-based activities, and liberatory worldmaking.

Contributors: Jordyn Alderman, Leen Al-Fatafta, Meryl Altman, María Claudia André, Andrea N. Baldwin, Carolyn Beer, Luisa Bieri, Rebecca Dawson, Misty De Berry, Danielle M. DeMuth, Emily Fairchild, Sara Youngblood Gregory, Letizia Guglielmo, Jeremy Hall, K. Melchor Hall, Linh U. Hua, Christine Keating, Charlotte Meehan, Brayden Milam, Isis Nusair, Montserrat Pérez-Toribio, Andrea Putala, Ariella Rotramel, Ann Russo, Kimberly Sanchez, Barbara L. Shaw, M. Gabriela Torres, Ayana K. Weekley, and Sharon R. Wesoky

The pressures Asian Americans feel to be socially and economically exceptional include an unspoken mandate to always be healthy. Nowhere is this more evident than in the expectation for Asian Americans to enter the field of medicine, principally as providers of care rather than those who require care. Pedagogies of Woundedness explores what happens when those considered model minorities critically engage with illness and medicine whether as patients or physicians.

James Kyung-Jin Lee considers how popular culture often positions Asian Americans as medical authorities and what that racial characterization means. Addressing the recent trend of writing about sickness, disability, and death, Lee shows how this investment in Asian American health via the model minority is itself a response to older racial forms that characterize Asian American bodies as diseased. Moreover, he pays attention to what happens when academics get sick and how illness becomes both methodology and an archive for scholars.

Pedagogies of Woundedness also explores the limits of biomedical “care,” the rise of physician chaplaincy, and the impact of COVID. Throughout his book and these case studies, Lee shows the social, ethical, and political consequences of these common (mis)conceptions that often define Asian Americans in regard to health and illness.

Pedagogues and Protesters recounts the year in daily journal entries by Stephen Peabody, a member of the class of 1769. The best surviving account of colonial college life, Peabody's journal documents relationships among students, faculty members, and administrators, as well as the author's relationships with other segments of Massachusetts society. To a full transcription of the entries, Conrad Edick Wright adds detailed annotation and an introduction that focuses on the journal's revealing account of daily life at America's oldest college.

Published in association with Massachusetts Historical Society

Engage fourteen essays from an international group of experts

There is little direct evidence for formal education in the Bible and in the texts of Second Temple Judaism and early Christianity. At the same time, pedagogy and character formation are important themes in many of these texts. This book explores the pedagogical purpose of wisdom literature, in which the concept of discipline (Hebrew musar) is closely tied to the acquisition of wisdom. It examines how and why the concept of musar came to be translated as paideia (education, enculturation) in the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible (Septuagint), and how the concept of paideia was deployed by ancient Jewish authors writing in Greek. The different understandings of paideia in wisdom and apocalyptic writings of Second Temple Judaism are this book's primary focus. It also examines how early Christians adapted the concept of paideia, influenced by both the Septuagint and Greco-Roman understandings of this concept.

Features

Pedagogy of Democracy re-interprets the U.S. occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1952 as a problematic instance of Cold War feminist mobilization rather than a successful democratization of Japanese women as previously argued. By combining three fields of research—occupation, Cold War, and postcolonial feminist studies—and examining occupation records and other archival sources, Koikari argues that postwar gender reform was one of the Cold War containment strategies that undermined rather than promoted women’s political and economic rights.

In a book that itself exemplifies the dialogic scholarship it proposes, Kay Halasek reconceives composition studies from a Bakhtinian perspective, focusing on both the discipline's theoretical assumptions and its pedagogies.

Framing her discussions at every level of the discipline—theoretical, historical, pedagogical—Halasek provides an overview of portions of the Bakhtinian canon relevant to composition studies, explores the implications of Mikhail Bakhtin's work in the teaching of writing and for current debates about the role of theory in composition studies, and provides a model of scholarship that strives to maintain dialogic balance between practice and theory, between composition studies and Bakhtinian thought.

Halasek's study ranges broadly across the field of composition, painting in wide strokes a new picture of the discipline, focusing on the finer details of the rhetorical situation, and teasing out the implications of Bakhtinian thought for classroom practice by examining the nature of critical reading and writing, the efficacy and ethics of academic discourse, student resistance, and critical and conflict pedagogy. The book ends by setting out a pedagogy of possibility, what Halasek terms elsewhere a "post-critical pedagogy" that redefines and redirects current discussions of home versus academic literacies and discourses.

In this interpretive commentary on Theaetetus, Gregory Kirk makes a major contribution to scholarship on Plato by emphasizing the relevance of the interpersonal dynamics between the interlocutors for the interpretation of the dialogue’s central arguments about knowledge. Kirk attends closely to the personalities of the participants in the dialogue, focusing especially on the unique demands faced by a student—in this case, Theaetetus—and the ways in which one can embrace or deflect the responsibilities of learning. Kirk’s approach gives equal consideration to the dual demands of dramatic interpretation and philosophical argument that constitute the unique character of the Platonic text, and he develops an original interpretation of the Theaetetus, concluding that the uncertainty that characterizes wisdom supersedes the certainty of knowledge.

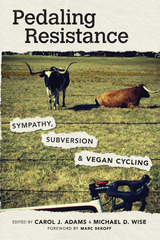

The essays in this collection explore the unity between cycling for health, work, competition, transport, and joy, and the issues of animal suffering, environmentalism, and speciesism inherent in veganism—all through lenses of class, race, gender, and disability. Pedaling Resistance illuminates themes of everyday resistance and boundary crossing to uncover the greater social and political issues that underlie the decisions to give up animal products and choose cycling over driving.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press