16 start with W start with W

“What Happens Is Neither / the end nor the beginning. / Yet we’re wired to look for signs,” offers the speaker of Angela Narciso Torres’s latest collection, which approaches motherhood, aging, and mourning through a series of careful meditations. In music, mantra, and prayer, Torres explores the spaces in and around grief—in varying proximity to it and from different vantage points. She writes both structurally formal poems that enfold the emotionality of loss and free verse that loosens the latch on memory and lets us into the sensory worlds of the speaker’s childhood and present. In poems set in two countries and homes, Torres considers what it means to leave a mark, vanish, and stay in one place. In a profound act of recollection and preservation, Torres shows us how to release part of ourselves but remain whole

What if the Invader is Beautiful explores the ineffable yet primal connections between outer and inner landscapes — the impact that the natural world has on the psychological terrain of our interior lives. Through compressed, musical, and often deeply mysterious language, the poems enact the extreme outer limits of emotional experience. Often set in equally extreme natural settings, the poems ride the knife edge between beauty and terror — exploring concepts of the sublime, the spiritual power of the elements, the redemptive beauty of flora and fauna, and the psychological freedom of wide-open spaces — and illuminate how deepening our connection to these elements is ultimately what will save us from our human afflictions of separation, isolation, and fear.

In this electrifying debut, lyric works to untangle slippery personal and political histories in the wake of a parent’s suicide. “When my father finally / died,” Vyas writes, “we [...] burned, / like an effigy, the voiceless body.” Grief returns us to elemental silence, where “the wind is a muted vowel in the brush of pine / branches” across American landscapes. These poems extend formal experimentation, caesurae, and enjambment to reach into the emptiness and fractures that remain. This language listens as much as it sings, asking: can we recover from the muting effects of British colonialism, American imperialism, patriarchy, and caste hierarchies? Which cultural legacies do we release in order to heal? Which do we keep alive, and which keep us alive? A monument to yesterday and a missive to tomorrow, When I Reach for Your Pulse reminds us of both the burden and the promise of inheritance. “[T]he wail outlasts / the dream,” but time falls like water and so “the stream survives its source.”

While Hoffman’s debut collection interrogated the mythos built around grief, inhabiting an Alaska of the mind, her stunning sophomore collection When There Was Light looks at the past for what it was.These poems map out a topography where global movements of diaspora and war live alongside personal reckonings: a house’s foreclosure, parents’ divorce, the indelible night spent drunk with a best friend “[lying] down inside a chronic row of corn.” Here, her father’s voice “is the stray dog barking / at the snow, believing the little strawberries grow wilder / against a field.” In these pages, she points to Russia and Poland and Germany, saying, “It was / another time. My people / another time. The synagogues burn decades / of new snow.” The brilliance of this collection illuminates the relationship between memory and language; “another time” means different, back then, gone and lost to us, and it means over and over, always, again. With this linguistic dexterity and lyrical tenderness, Hoffman’s work bridges private and public histories, reminding us of the years cloaked in shadows and the years when there was light.

In response to this crime, Donnelly traces the consequences of ignorance, denial, bargaining, complicity, and finally revelation that reverberated through his and his loved ones’ lives for five decades. His discovery of this catalyzing violation not only recontextualizes the siblings’ shared history, but inflects the present as—finding analogues of his sister’s abuse in the classical canon—he remembers his escape from home into spiritual disciplines and the study of dead languages. Revisiting the evolution of his own sexuality, he remembers singing a Byrd Mass after a night at a gay bathhouse, characterizing the tenor and bass as “two wrestling saints,” “lowest of the four voices— / once I thought I saw them kiss each other’s faces.”

And that—recovering glimpses of his sister’s unknowable interiority, reckoning with a truth that is unbearable and inescapable—is this book’s difficult and endless work. In the wake of a particular kind of harm, Willow Hammer seems to suggest, justice may be a wishful concept—but that doesn’t preclude testimony and salvage. “Now” documents the poet’s arrival at this compromise: “I remember my / little sister that was, / little willow of glass / upon whom he laid / his hammer hands.” There is no revocation of the hands, but with tenderness, wit, and fury, Donnelly’s lyrics refuse to let their shadow obscure his sister’s recovery of her own agency.

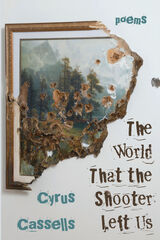

In the aftermath of the Stand Your Ground killing of his close friend’s father, poet Cassells explores, in his most fearless book to date, the brutality, bigotry, and betrayal at the heart of current America. Taking his cue from the Civil Rights and Vietnam War era poets and songwriters who inspired him in his youth, Cassells presents The World That the Shooter Left Us, a frank, bulletin-fierce indictment of unraveling democracy in an embattled America, in a world still haunted by slavery, by Guernica, Hiroshima, and the Holocaust, by climate catastrophe, by countless battles, borders, and broken promises—adding new grit, fire, and luster to his forty-year career as a dedicated and vital American poet.

“The / drugs, the page, none of it is here. That was years ago,” Daniel Levin writes in his debut collection of poems, trying to create an inventory of blank spaces, to describe the persistent presence — the psychological furniture — of what no longer exists. “There was a room. I lived there. / Now, I can’t find it anymore.”

Written in the wake of the media storm surrounding the revelation of the Sarah Lawrence cult, interrogating the constructs of confessionalism and journalistic epistemology after the release of memoirs and viral articles and a Hulu docu-series, Worms, Dirt considers the soil beneath the story playing out aboveground. These poems are a unique telling of two kinds of departure – leaving a cult and exiting a relationship. They weave together fragments and elisions of memory — “Was any of it right? Did any of it happen the way / You remembered?” — reverse engineering a story from the aftermath — “The piece you still can’t find. It must be true. He was // Gentle. Sometimes, he was gentle.” Devastating and open-hearted, these pages transcribe transformation and reconstruction of self, survival, reckoning. They confront the intimate betrayals of belonging to a high-control group or seeking love from the wrong romantic relationships. These lyrics confront horror and a fragile hope in their recognition of this inconceivable thing, the soft flesh smothered by the scar: “The hands’ capacity / For gentleness even as you watched them, in disbelief, dismantle you.”

Traversing New York and New Hampshire and landing in Los Angeles, Levin treats the things we leave behind as the material from which we grow. Most striking about Worms, Dirt is its lyrical metacommentary — as a book about writing a book, it constantly refuses the constraints of the imposed narrative memoir and the parasitic appetite for sensationalism, easily commodified true crime, and flattening characterizations of victims and villains. “For I am at work, writing this / For I have accrued so many reasons to live.”

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press