Alcohol in Ancient Mexico reconstructs the variety and extent of distillation traditions in the ancient cultures of Mexico, describing in detail the various plants and processes used to make such beverages, their prevalence, and their significance for local culture.

The art of distillation arrived in Mexico with the Spaniards in the sixteenth century. However, well before that time, native skills and available resources had contributed to a well-developed tradition of intoxicating beverages, many of which are still produced and consumed.

In the 1930’s Henry Bruman visited various Mexican and Central American Indian tribes to reconstruct the variety and extent of these ancient traditions. He discerned five distinct areas defined by the culturally most significant beverages, all superimposed over the great mescal wine region. Within these five areas he noted wine made from cactus, cactus fruit, cornstalks, and mesquite pods; beer from sprouted maize; and fermented sap from pulque agaves.

Outside the mescal region he observed widespread consumption in the Yucatan of a wine made from fermented honey and balché bark, plus lesser-known beverages in other regions. He also observed the frequent inclusion in the fermentation process of alkaloid-bearing ingredients such as peyote and tobacco, plants whose roots or bark contain saponins—which act as cardiac poisons—and even poisons from certain toads.

Alcohol in Ancient Mexico also considers the relative absence of alcoholic drink in the southwestern United States, the introduction of sills following the Spanish conquest, and possible sources for the introduction of coconut wine.

Previously unpublished, the research presented here retains its relevance today, and the photographs offer a fascinating glimpse at a traditional world that has now almost vanished.

Alcohol in Latin America is the first interdisciplinary study to examine the historic role of alcohol across Latin America and over a broad time span. Six locations—the Andean region, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Guatemala, and Mexico—are seen through the disciplines of anthropology, archaeology, art history, ethnohistory, history, and literature. Organized chronologically beginning with the pre-colonial era, it features five chapters on Mesoamerica and five on South America, each focusing on various aspects of a dozen different kinds of beverages.

An in-depth look at how alcohol use in Latin America can serve as a lens through which race, class, gender, and state-building, among other topics, can be better understood, Alcohol in Latin America shows the historic influence of alcohol production and consumption in the region and how it is intimately connected to the larger forces of history.

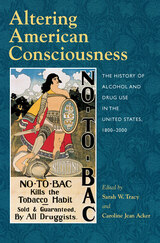

Yet, if the use of drugs is a constant in American history, the way they have been perceived has varied extensively. Just as the corrupting cigarettes of the early twentieth century ("coffin nails" to contemporaries) became the glamorous accessory of Hollywood stars and American GIs in the 1940s, only to fall into public disfavor later as an unhealthy and irresponsible habit, the social significance of every drug changes over time.

The essays in this volume explore these changes, showing how the identity of any psychoactive substance—from alcohol and nicotine to cocaine and heroin—owes as much to its users, their patterns of use, and the cultural context in which the drug is taken, as it owes to the drug's documented physiological effects. Rather than seeing licit drugs and illicit drugs, recreational drugs and medicinal drugs, "hard" drugs and "soft" drugs as mutually exclusive categories, the book challenges readers to consider the ways in which drugs have shifted historically from one category to another.

In addition to the editors, contributors include Jim Baumohl, Allan M. Brandt, Katherine Chavigny, Timothy Hickman, Peter Mancall, Michelle McClellan, Steven J. Novak, Ron Roizen, Lori Rotskoff, Susan L. Speaker, Nicholas Weiss, and William White.

Affiliation with Alcoholics Anonymous parallels religious conversion, according to David R. Rudy in this timely study of the most famous self-help organization in the world.

Drinkers who commit themselves to Alcoholics Anonymous embrace the radically different life-style, the altered world of the convert.

To understand this conversion and, more important, to get a grip on the even deeper mystery of alcoholism itself, Rudy sought to answer these three questions: What processes are involved in becoming alcoholic? How does the alcoholic affiliate with, and become committed to, A. A.’s belief system? What is the relationship between the world of A. A. members and that constructed by alcohologists?

Rudy establishes the history and structure of A. A. and examines the organization’s relationship to dominant sociological models, theories, and definitions of alcoholism.

In this audacious memoir, William Cobb reveals the tumultuous creative life of a distinguished practitioner of southern and Alabama storytelling. As poignant and inspiring as his own fiction, Captain Billy’s Troopers traces Cobb’s early life, education, and struggles with alcohol and the debilitating condition normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH).

Like a curving river, the broad sweep of Cobb’s turbulent life includes both startling cataracts and desultory eddies, leading sometimes into shadows or opening into unexpected sunlight. With unsentimental clarity, Cobb recounts coming of age in his native Demopolis in the churning middle years of the twentieth century. It’s there he has his first tantalizing tastes of alcohol and begins to drink habitually. Readers then travel with Cobb to Livingston University (now the University of West Alabama) and then on to Vanderbilt University. Along the way, readers relish his first experiences of love and success as a writer, leading to a career as a professor of writing at Alabama College (now the University of Montevallo) in 1963.

From there Cobb’s struggles with alcohol and depression lead to elongated years of tumbling creative output and the collapse of his marriage. The summer of 1984 found Cobb in rehab, the first step in his path to recovery. His unflinching memoir narrates both the milestones and telling details of his intense therapy and years in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). In the sober thirty years since, Cobb has published a string of critically praised novels and a prize-winning collection of short stories. The capstone of his comeback was winning the Harper Lee Award in 2007 for distinguished fiction writing.

In 2000, shortly after retiring, Cobb developed NPH, which upset his sense of balance and triggered dementia symptoms and other maladies. Nine years later in 2009, brain surgery brought Cobb a dramatic recovery, which began the third act in his writing career. Vital, honest, and entertaining, Captain Billy’s Troopers captures the life of an Alabama original.

“Old stories are universal and want to be told. To bring those stories out into the world as a vehicle for navigating sobriety and recovery is a glorious thing.

I was hired to be an addictions counselor for the therapeutic community at the Frederick County Adult Detention Center. Susan Gordon encouraged me to tell them stories. I thought she was crazy, but I trusted her judgment and told them stories. The impact those stories had on those men changed my life. I worked in addictions for 15 years, taking those stories with me to very agency in which I worked. The women at the Center 4 Clean Start in Salisbury, MD were every bit as receptive to story as the men who were in jail.”

--Beth Ohlsson

In A Drunkard's Defense, Michele Rotunda examines a variety of court cases to explore the attitudes of nineteenth-century physicians, legal professionals, temperance advocates, and ordinary Americans toward the relationship between drunkenness, violence, and responsibility, providing broader insights into the country's complicated relationship with alcohol.

The setting for the story is Hungry Hill, an Irish-Catholic working-class neighborhood in Springfield , Massachusetts . The author recounts her sad and turbulent story with remarkable clarity, humor, and insight, punctuating the narrative with occasional fictional scenes that allow the adult Carole to comment on her teenage experiences and to probe the impact of her mother's death and her father's alcoholism.

Addiction is easy to fall into and hard to escape. It destroys the lives of individuals, and has a devastating cost to society. The National Institute of Health estimates seventeen million adults in the United States are alcoholics or have a serious problem with alcohol. At the same time, the country is seeing entire communities brought to their knees because of opioid additions. These scourges affect not only those who drink or use drugs but also their families and friends, who witness the horror of addiction. With Out of the Wreck I Rise, Neil Steinberg and Sara Bader have created a resource like no other—one that harnesses the power of literature, poetry, and creativity to illuminate what alcoholism and addiction are all about, while forging change, deepening understanding, and even saving lives.

Structured to follow the arduous steps to sobriety, the book marshals the wisdom of centuries and explores essential topics, including the importance of time, navigating family and friends, relapse, and what Raymond Carver calls “gravy,” the reward that is recovery. Each chapter begins with advice and commentary followed by a wealth of quotes to inspire and heal. The result is a mosaic of observations and encouragement that draws on writers and artists spanning thousands of years—from Seneca to David Foster Wallace, William Shakespeare to Patti Smith. The ruminations of notorious drinkers like John Cheever, Charles Bukowski, and Ernest Hemingway shed light on the difficult process of becoming sober and remind the reader that while the literary alcoholic is often romanticized, recovery is the true path of the hero.

Along with traditional routes to recovery—Alcoholics Anonymous, out-patient therapy, and intensive rehabilitation programs—this literary companion offers valuable support and inspiration to anyone seeking to fight their addiction or to a struggling loved one.

Featuring Charles Bukowski, John Cheever, Dante, Ricky Gervais, Ernest Hemingway, Billie Holiday, Anne Lamott, John Lennon, Haruki Murakami, Anaïs Nin, Mary Oliver, Samuel Pepys, Rainer Maria Rilke, J. K. Rowling, Patti Smith, Kurt Vonnegut, and many more.

In The Prohibition Hangover, Garrett Peck explores the often-contradictory social history of alcohol in America, from the end of Prohibition in 1933 to the twenty-first century. For Peck, Repeal left American society wondering whether alcohol was a consumer product or a controlled substance, an accepted staple of social culture or a danger to society. Today the legal drinking age, binge drinking, the neo-prohibitionist movement led by Mothers Against Drunk Driving, the 2005 Supreme Court decision in Granholm v. Heald that rejected discriminatory curbs on wine sales, the health benefits of red wine, advertising, and other issues remain highly contested.

Based on primary research, including hundreds of interviews with those on all sides, clergy, bar and restaurant owners, public health advocates, citizen crusaders, industry representatives, and more, as well as secondary sources, The Prohibition Hangover provides a panoramic assessment of alcohol in American culture. Traveling through the California wine country, the beer barrel backroads of New England and Pennsylvania, and the blue hills of Kentucky's bourbon trail, Peck places the concerns surrounding alcohol use within the broader context of American history, religious traditions, and governance.

Society is constantly evolving, and so are our drinking habits. Cutting through the froth and discarding the maraschino cherries, The Prohibition Hangover examines the modern American temperament toward drink amid the $189-billion-dollar-a-year industry that defines itself by the production, distribution, marketing, and consumption of alcoholic beverages.

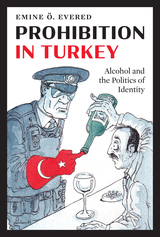

A social history of alcohol, identity, secularism, and modernization from the late Ottoman and early Turkish republican eras to the present day.

Prohibition in Turkey investigates the history of alcohol, its consumption, and its proscription as a means to better understand events and agendas of the late Ottoman and early Turkish republican eras. Through a comprehensive examination of archival, literary, popular culture, media, and other sources, it unveils a traditionally overlooked—and even excluded—aspect of human history in a region that many do not associate with intoxicants, inebriation, addiction, and vigorous wet-dry debates.

Historian Emine Ö. Evered’s account uniquely chronicles how the Turko-Islamic Ottoman Empire developed strategies for managing its heterogeneous communities and their varied rights to produce, market, and consume alcohol, or to simply abstain. The first author to reveal this experience’s connections with American Prohibition, she demonstrates how—amid modernization, sectarianism, and imperial decline—drinking practices reflected, shifted, and even prompted many of the changes that were underway and that hastened the empire’s collapse. Ultimately, Evered’s book reveals how Turkey’s alcohol question never went away but repeatedly returns in the present, in matters of popular memory, public space, and political contestation.

- In 1889, Pud Galvin tried a testosterone-derived "elixir" to help him pile up some of his 646 complete games.

- Sandy Koufax needed Codeine and an anti-inflammatory used on horses to pitch through his late-career elbow woes.

- Players returning from World War II mainstreamed the use of the amphetamines they had used as servicemen.

- Vida Blue invited teammates to cocaine parties, Tim Raines used it to stay awake on the bench, and Will McEnaney snorted it between innings.

The development of an American wine ethos.

The history of wine is a tale of capitalist production and consumer experience, and early Americans embraced the idea of having their own wine culture. But many began to believe that excessive alcohol consumption had become a moral, ethical, economic, political, social, and health conundrum. The result was a national on-again, off-again relationship with the concept of an American wine culture.

Citizens struggled to build a wine culture patterned after their diasporic European custom of wine as a moderating beverage that was part of a healthy diet. Yet, as America grew, untold attempts to create a wine culture failed due to climate, pests, diseases, wars, and depressions, resulting in some people considering the nation an alcoholic republic. Thus began an anti-alcohol culture war aimed at restricting or prohibiting alcoholic beverages.

With the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment (Prohibition), a culture war started between wet and dry proponents. After the repeal of Prohibition, the decimated wine industry responded by forming the Wine Institute to rebrand wine’s role in American society, after which neoprohibitionists attempted to restrict alcohol availability and consumption. To confront these aggressive actions, the Wine Institute hired politically trained John A. De Luca to navigate the new attacks and pushed for rebranding wine as a cultural spirit with health benefits.

Healing roles and rituals involving alcohol are a major source of power and identity for women and men in Highland Chiapas, Mexico, where abstention from alcohol can bring a loss of meaningful roles and of a sense of community. Yet, as in other parts of the world, alcohol use sometimes leads to abuse, whose effects must then be combated by individuals and the community.

In this pioneering ethnography, Christine Eber looks at women and drinking in the community of San Pedro Chenalhó to address the issues of women’s identities, roles, relationships, and sources of power. She explores various personal and social strategies women use to avoid problem drinking, including conversion to Protestant religions, membership in cooperatives or Catholic Action, and modification of ritual forms with substitute beverages.

The book’s women-centered perspective reveals important data on women and drinking not reported in earlier ethnographies of Highland Chiapas communities. Eber’s reflexive approach, blending the women’s stories, analyses, songs, and prayers with her own and other ethnographers’ views, shows how Western, individualistic approaches to the problems of alcohol abuse are inadequate for understanding women’s experiences with problem and ritual drinking in a non-Western culture.

In a new epilogue, Christine Eber describes how events of the last decade, including the Zapatista uprising, have strengthened women's resolve to gain greater control over their lives by controlling the effects of alcohol in the community.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press