3 books about Mencken, H. L. (Henry Louis)

Fitzgerald's Mentors

Edmund Wilson, H. L. Mencken, and Gerald Murphy

Ronald Berman

University of Alabama Press, 2012

A fresh and compelling study of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s intellectual friendship with Edmund Wilson, H. L. Mencken, and Gerald Murphy

Fitzgerald was shaped through his engagements with key literary and artistic figures in the 1920s. This book is about their influence— and also about the ways that Fitzgerald defended his own ideas about writing. Influence was always secondary to independence.

Fitzgerald’s education began at Princeton with Edmund Wilson. There Wilson imparted to Fitzgerald many ideas about education and literary values, among them respect for the classics and an acute awareness of literary tradition.

In New York H. L. Mencken impressed upon Fitzgerald his belief in the stifling effect of public morality on writers. Furthermore, Mencken’s The American Language changed Fitzgerald’s thinking about the power of everyday language.

After moving to France in 1924, Fitzgerald’s intellectual life took a very different turn. Gerald Murphy exposed him to the visual arts— including the work of Fernand Leger, Pablo Picasso, and Man Ray—and to people deeply interested in the perception of art in daily life. Equally important, Fitzgerald had many discussions about artistic values with both Gerald and Sara Murphy.

[more]

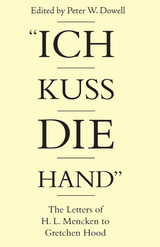

"Ich Kuss Die Hand"

The Letters of H. L. Mencken To Gretchen Hood

H. L. Mencken

University of Alabama Press, 1986

What started as a correspondence between an illustrious personage and an ardent fan developed into a friendship between two individuals with congenial temperaments, interests, and tastes

“Ich Kuss Die Hand”: The Letters of H. L. Mencken to Gretchen Hood relates an episode in Mencken's life that has received only passing mention from his biographers. Gretchen Hood's acquaintance with the journalistic life of Washington formed a bond with Mencken, who thought of himself, first and foremost, as an inveterate newspaperman (they playfully entertained the idea of starting their own Washington newspaper), and she had a ready appreciation for his performances as a connoisseur of the Washington political spectacle. Mencken, the amateur musician and music buff, respected her talent and professional background.

His letters indicate that he found in her an intelligent, witty, and charming respondent to his characteristic traits of personality and style. She both flattered his ego and challenged him to exhibit his celebrated manner at its best. On her part, Hood was not simply awestruck by Mencken's attentions but met them with her independent verve. “Nothing scared me,” she later said of her attitude; “ready to take on all comers.” Mencken liked to refer to her as “a licensed outlaw,” a designation that captures his impression of her and describes as well the fashionable unconventionality, which fueled the Mencken vogue.

Mencken wrote Hood over two hundred letters, and she must have written him about the same number. For much of the time they corresponded, they exchanged several letters every month, sometimes as many as four or five a week. As their communications blossomed into a four-year friendship, personal meetings soon supplemented the flow of letters.

“Ich Kuss Die Hand”: The Letters of H. L. Mencken to Gretchen Hood relates an episode in Mencken's life that has received only passing mention from his biographers. Gretchen Hood's acquaintance with the journalistic life of Washington formed a bond with Mencken, who thought of himself, first and foremost, as an inveterate newspaperman (they playfully entertained the idea of starting their own Washington newspaper), and she had a ready appreciation for his performances as a connoisseur of the Washington political spectacle. Mencken, the amateur musician and music buff, respected her talent and professional background.

His letters indicate that he found in her an intelligent, witty, and charming respondent to his characteristic traits of personality and style. She both flattered his ego and challenged him to exhibit his celebrated manner at its best. On her part, Hood was not simply awestruck by Mencken's attentions but met them with her independent verve. “Nothing scared me,” she later said of her attitude; “ready to take on all comers.” Mencken liked to refer to her as “a licensed outlaw,” a designation that captures his impression of her and describes as well the fashionable unconventionality, which fueled the Mencken vogue.

Mencken wrote Hood over two hundred letters, and she must have written him about the same number. For much of the time they corresponded, they exchanged several letters every month, sometimes as many as four or five a week. As their communications blossomed into a four-year friendship, personal meetings soon supplemented the flow of letters.

[more]

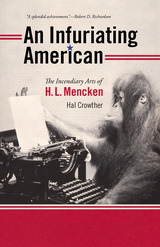

An Infuriating American

The Incendiary Arts of H. L. Mencken

Hal Crowther

University of Iowa Press, 2014

As American journalism shape-shifts into multimedia pandemonium and seems to diminish rapidly in influence and integrity, the controversial career of H. L. Mencken, the most powerful individual journalist of the twentieth century, is a critical text for anyone concerned with the balance of power between the free press, the government, and the corporate plutocracy. Mencken, the belligerent newspaperman from Baltimore, was not only the most outspoken pundit of his day but also, by far, the most widely read, and according to many critics the most gifted American writer ever nurtured in a newsroom—a vanished world of typewriter banks and copy desks that electronic advances have precipitously erased.

Nearly 60 years after his death, Mencken’s memory and monumental verbal legacy rest largely in the hands of literary scholars and historians, to whom he will always be a curious figure, unchecked and alien and not a little distasteful. No faculty would have voted him tenure. Hal Crowther, who followed in many of Mencken’s footsteps as a reporter, magazine editor, literary critic, and political columnist, focuses on Mencken the creator, the observer who turned his impressions and prejudices into an inimitable group portrait of America, painted in prose that charms and glowers and endures. Crowther, himself a working polemicist who was awarded the Baltimore Sun’s Mencken prize for truculent commentary, examines the origin of Mencken’s thunderbolts—where and how they were manufactured, rather than where and on whom they landed.

Mencken was such an outrageous original that contemporary writers have made him a political shuttlecock, defaming or defending him according to modern conventions he never encountered. Crowther argues that loving or hating him, admiring or despising him are scarcely relevant. Mencken can inspire and he can appall. The point is that he mattered, at one time enormously, and had a lasting effect on the national conversation. No writer can afford to ignore his craftsmanship or success, or fail to be fascinated by his strange mind and the world that produced it. This book is a tribute—though by no means a loving one—to a giant from one of his bastard sons.

Nearly 60 years after his death, Mencken’s memory and monumental verbal legacy rest largely in the hands of literary scholars and historians, to whom he will always be a curious figure, unchecked and alien and not a little distasteful. No faculty would have voted him tenure. Hal Crowther, who followed in many of Mencken’s footsteps as a reporter, magazine editor, literary critic, and political columnist, focuses on Mencken the creator, the observer who turned his impressions and prejudices into an inimitable group portrait of America, painted in prose that charms and glowers and endures. Crowther, himself a working polemicist who was awarded the Baltimore Sun’s Mencken prize for truculent commentary, examines the origin of Mencken’s thunderbolts—where and how they were manufactured, rather than where and on whom they landed.

Mencken was such an outrageous original that contemporary writers have made him a political shuttlecock, defaming or defending him according to modern conventions he never encountered. Crowther argues that loving or hating him, admiring or despising him are scarcely relevant. Mencken can inspire and he can appall. The point is that he mattered, at one time enormously, and had a lasting effect on the national conversation. No writer can afford to ignore his craftsmanship or success, or fail to be fascinated by his strange mind and the world that produced it. This book is a tribute—though by no means a loving one—to a giant from one of his bastard sons.

[more]

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2024

The University of Chicago Press