53 start with J start with J

Jack London’s fiction has been studied previously for its thematic connections to the ocean, but Jack London and the Sea marks the first time that his life as a writer has been considered extensively in relationship to his own sailing history and interests. In this new study, Anita Duneer claims a central place for London in the maritime literary tradition, arguing that for him romance and nostalgia for the Age of Sail work with and against the portrayal of a gritty social realism associated with American naturalism in urban or rural settings. The sea provides a dynamic setting for London’s navigation of romance, naturalism, and realism to interrogate key social and philosophical dilemmas of modernity: race, class, and gender. Furthermore, the maritime tradition spills over into texts that are not set at sea.

Jack London and the Sea does not address all of London’s sea stories, but rather identifies key maritime motifs that influenced his creative process. Duneer’s critical methodology employs techniques of literary and cultural analysis, drawing on extensive archival research from a wealth of previously unpublished biographical materials and other sources. Duneer explores London’s immersion in the lore and literature of the sea, revealing the extent to which his writing is informed by travel narratives, sensational sea yarns, and the history of exploration, as well as firsthand experiences as a sailor in the San Francisco Bay and Pacific Ocean.

Organized thematically, chapters address topics that interested London: labor abuses on “Hell-ships” and copra plantations, predatory and survival cannibalism, strong seafaring women, and environmental issues and property rights from San Francisco oyster beds to pearl diving in the Paumotos. Through its examination of the intersections of race, class, and gender in London’s writing, Jack London and the Sea plumbs the often-troubled waters of his representations of the racial Other and positions of capitalist and colonial privilege. We can see the manifestation of these socioeconomic hierarchies in London’s depiction of imperialist exploitation of labor and the environment, inequities that continue to reverberate in our current age of global capitalism.

A reporter's firsthand portrait of formerly enslaved Jamaicans in the years after emancipation

John Bigelow’s Jamaica in 1850 provided an important document in the antislavery movement in the United States and Great Britain. Jamaica’s economy had collapsed after the 1838 emancipation. American supporters of enslavement used the Jamaican example to argue that abolition at home would unleash economic and social chaos. Bigelow’s vivid eyewitness reporting undermined that widely held view by proving Jamaica’s problems originated in the incompetence of absentee white planters and an obsolete colonial system. As Bigelow showed, many once-enslaved Jamaicans had in fact become successful small-scale landowners in the twelve years after emancipation while the large plantations languished.

This captivating new biography by Don Faber recounts the fascinating story of Strang’s path from impoverished New York farm boy to one of the most colorful and contentious personalities in Michigan history. Avoiding the nonsense, misinformation, and twisted facts so prevalent about the man, readers meet the historical Strang stripped of myth, demonization, and popular fancy—a true celebrity of the mid-nineteenth century who both shaped and was shaped by the colorful times in which he lived. This book will appeal to readers interested in the history of Michigan, the nineteenth century, and the Second Great Awakening.

Devoted fans and scholars of Jane Austen—as well as skeptics—will rejoice at Tony Tanner’s superb book on the incomparable novelist. Distilling twenty years of thinking and writing about Austen, Tanner treats in fresh and illuminating ways the questions that have always occupied her most perceptive critics. How can we reconcile the limited social world of her novels with the largeness of her vision? How does she deal with depicting a once-stable society that was changing alarmingly during her lifetime? How does she express and control the sexuality and violence beneath the well-mannered surface of her milieu? How does she resolve the problems of communication among characters pinioned by social reticences?

Tanner guides us through Austen’s novels from relatively sunny early works to the darker, more pessimistic Persuasion and fragmentary Sanditon—a journey that takes her from acceptance of a society maintained by landed property, family, money, and strict propriety through an insistence on the need for authentication of these values to a final skepticism and even rejection. In showing her progress from a parochial optimism to an ability to encompass her whole society, Tanner renews our sense of Jane Austen as one of the great novelists, confirming both her local and abiding relevance.

This illuminating, entertaining, up-to-date companion is the only general guide to Jane Austen, her work, and her world. Josephine Ross explores the literary scene during the time Austen's works first appeared: the books considered classics then, the "horrid novels" and romances, and the grasping publishers. She looks at the architecture and décor of Austen's era that made up "the profusion and elegance of modern taste." Regency houses for instance, Chippendale furniture, and "picturesque scenery." On a smaller scale she answers questions that may baffle modern readers. What, for example, was "hartshorn"? How did Lizzy Bennet "let down" her gown to hide her muddy petticoat? Ross shows us the fashions, and the subtle ways Jane Austen used clothes to express character. Courtship, marriage, adultery, class and "rank," mundane tasks of ordinary life, all appear, as does the wider political and military world.

This book will add depth to all readers' enjoyment of Jane Austen, whether confirmed addicts or newcomers wanting to learn about one of the world's most popular and enduring writers.

Brilliantly edited by Kathryn Sutherland, Jane Austen: The Chawton Letters uses Austen’s letters drawn from the collection held at Jane Austen’s House Museum at her former home in Chawton, Hampshire, to tell her life story. At age twenty-five, Austen left her first home, Steventon, Hampshire, for Bath. In 1809, she moved to Chawton, which was to be her home for the remainder of her short life. In her correspondence, we discover Austen’s relish for her regular visits to the shops and theaters of London, as well as the quieter routines of village life. We learn of her anxieties about the publication of Pride and Prejudice, her care in planning Mansfield Park, and her hilarious negotiations over the publication of Emma. (To her sister, Cassandra, Austen calls her publisher John Murray, “a Rogue, of course, but a civil one.”) Throughout, the Chawton letters testify to Jane’s close ties with her family, especially her sister, and the most moving letter is written by Cassandra just days after Jane’s death. The collection also reproduces pages from the letters in Austen’s own distinctive hand.

This collection makes a delightful modern-day keepsake from one of the world’s best-loved writers on the two-hundredth anniversary of her death.

"By looking at the ways in which Austen domesticates the gothic in Northanger Abbey, examines the conventions of male inheritance and its negative impact on attempts to define the family as a site of care and generosity in Sense and Sensibility, makes claims for the desirability of 'personal happiness as a liberating moral category' in Pride and Prejudice, validates the rights of female authority in Emma, and stresses the benefits of female independence in Persuasion, Johnson offers an original and persuasive reassessment of Jane Austen's thought."—Kate Fullbrook, Times Higher Education Supplement

Brilliantly edited by Kathryn Sutherland, Jane Austen: Writer in the World offers a life story told through the author's personal possessions. In her teenage notebooks, literary jokes give a glimpse of her family’s shared love of reading and satire, which can be seen in the subtler humor of Austen’s published work. Pieces from Austen’s hand-copied collection of sheet music reveal how music was used to create networks far more intricate than the simple pleasures of home recital. A beautiful brown silk pelisse-coat, together with lively letters between Austen and Cassandra, give insight into her views on fashion. All feature in this lavishly illustrated collection, along with homemade booklets in which she composed her novels, portraits made of Austen during her lifetime, and much more. Also included are objects associated with the era in which Austen lived: newspaper articles, naval logbooks, and contemporary political cartoons, shedding light on Austen’s wider social and political worlds.

This collection makes a delightful modern-day keepsake from one of the world’s best-loved writers on the two-hundredth anniversary of her death.

Jane Austen completed only six novels, but enduring passion for the author and her works has driven fans to read these books repeatedly, in book clubs or solo, while also inspiring countless film adaptations, sequels, and even spoofs involving zombies and sea monsters. Austen’s lasting appeal to both popular and elite audiences has lifted her to legendary status. In Jane Austen’s Cults and Cultures, Claudia L. Johnson shows how Jane Austen became “Jane Austen,” a figure intensely—sometimes even wildly—venerated, and often for markedly different reasons.

This book traces the development of feminist consciousness in Japan from 1871 to 1941. Taeko Shibahara uncovers some fascinating histories as she examines how middle-class women navigated between domestic and international influences to form ideologies and strategies for reform. They negotiated a humanitarian space as Japan expanded its nationalist, militarist, imperialist, and patriarchal power.

Focusing on these women's political awakening and activism, Shibahara shows how Japanese feminists channeled and adapted ideas selected from international movements and from interactions with mainly American social activists.

Japanese Women and the Transnational Feminist Movement before World War II also connects the development of international contacts with the particular contributions of Ichikawa Fusae to the suffrage movement, Ishimoto Shidzue to the birth control movement, and Gauntlett Tsune to the peace movement by touching on issues of poverty, prostitution, and temperance. The result provides a window through which to view the Japanese women's rights movement with a broader perspective.

In this groundbreaking new study—the first extended examination of the ideas of Lincoln and Jefferson—Hatzenbuehler provides readers with a succinct guide to their opinions, comparing and contrasting their reasoned judgments on America’s republican form of government. Each chapter is devoted to one key area of common interest: race and slavery, the pros and cons of political parties, state rights versus federal authority, religion and the presidency, presidential powers under the Constitution, or the proper political economy for a republic. Relying on the pair’s own words in their letters, writings, and speeches, Hatzenbuehler explores similarities and differences between the two men on contentious issues. Both, for instance, wrote that they were antislavery, but Jefferson never acted on this belief, while Lincoln moved toward a constitutional amendment banning slavery. The book’s title, taken from the Gettysburg Address, builds on both presidents’ expectations that Americans should dedicate themselves to the unfinished work of returning the nation to its founding principles.

Jefferson and Lincoln wrestled with many of the same issues and ideas that intrigue and divide Americans today. In his thought-provoking work, Hatzenbuehler details how the two presidents addressed these issues and ideas, which are essential to understanding not only America’s history but also the continuing influence of the past on the present.

In this masterly history, Lemire uses newly opened archives to explore how Jerusalem’s elite residents of differing faiths cooperated through an intercommunity municipal council they created in the mid-1860s to administer the affairs of all inhabitants and improve their shared city. These residents embraced a spirit of modern urbanism and cultivated a civic identity that transcended religion and reflected the relatively secular and cosmopolitan way of life of Jerusalem at the time. These few years would turn out to be a tipping point in the city’s history—a pivotal moment when the horizon of possibility was still open, before the council broke up in 1934, under British rule, into separate Jewish and Arab factions. Uncovering this often overlooked diplomatic period, Lemire reveals that the struggle over Jerusalem was not historically inevitable—and therefore is not necessarily intractable. Jerusalem 1900 sheds light on how the Holy City once functioned peacefully and illustrates how it might one day do so again.

German Jews were fully assimilated and secularized in the nineteenth century—or so it is commonly assumed. In Jewish Scholarship and Culture in the Nineteenth Century, Nils Roemer challenges this assumption, finding that religious sentiments, concepts, and rhetoric found expression through a newly emerging theological historicism at the center of modern German Jewish culture.

Modern German Jewish identity developed during the struggle for emancipation, debates about religious and cultural renewal, and battles against anti-Semitism. A key component of this identity was historical memory, which Jewish scholars had begun to infuse with theological perspectives beginning in the 1850s. After German reunification in the early 1870s, Jewish intellectuals reevaluated their enthusiastic embrace of liberalism and secularism. Without abandoning the ideal of tolerance, they asserted a right to cultural religious difference for themselves--an ideal they held to even more tightly in the face of growing anti-Semitism. This newly re-theologized Jewish history, Roemer argues, helped German Jews fend off anti-Semitic attacks by strengthening their own sense of their culture and tradition.

Despite much study of Viennese culture and Judaism between 1890 and 1914, little research has been done to examine the role of Jewish women in this milieu. Rescuing a lost legacy, Jewish Women in Fin de Siècle Vienna explores the myriad ways in which Jewish women contributed to the development of Viennese culture and participated widely in politics and cultural spheres.

Areas of exploration include the education and family lives of Viennese Jewish girls and varying degrees of involvement of Jewish women in philanthropy and prayer, university life, Zionism, psychoanalysis and medicine, literature, and culture. Incorporating general studies of Austrian women during this period, Alison Rose also presents significant findings regarding stereotypes of Jewish gender and sexuality and the politics of anti-Semitism, as well as the impact of German culture, feminist dialogues, and bourgeois self-images.

As members of two minority groups, Viennese Jewish women nonetheless used their involvement in various movements to come to terms with their dual identity during this period of profound social turmoil. Breaking new ground in the study of perceptions and realities within a pivotal segment of the Viennese population, Jewish Women in Fin de Siècle Vienna applies the lens of gender in important new ways.

While it is common knowledge that Jews were prominent in literature, music, cinema, and science in pre-1933 Germany, the fascinating story of Jewish co-creation of modern German theatre is less often discussed. Yet for a brief time, during the Second Reich and the Weimar Republic, Jewish artists and intellectuals moved away from a segregated Jewish theatre to work within canonic German theatre and performance venues, claiming the right to be part of the very fabric of German culture. Their involvement, especially in the theatre capital of Berlin, was of a major magnitude both numerically and in terms of power and influence. The essays in this stimulating collection etch onto the conventional view of modern German theatre the history and conflicts of its Jewish participants in the last third of the nineteenth and first third of the twentieth centuries and illuminate the influence of Jewish ethnicity in the creation of the modernist German theatre.

The nontraditional forms and themes known as modernism date roughly from German unification in 1871 to the end of the Weimar Republic in 1933. This is also the period when Jews acquired full legal and trade equality, which enabled their ownership and directorship of theatre and performance venues. The extraordinary artistic innovations that Germans and Jews co-created during the relatively short period of this era of creativity reached across the old assumptions, traditions, and prejudices that had separated people as the modern arts sought to reformulate human relations from the foundations to the pinnacles of society.

The essayists, writing from a variety of perspectives, carve out historical overviews of the role of theatre in the constitution of Jewish identity in Germany, the position of Jewish theatre artists in the cultural vortex of imperial Berlin, the role played by theatre in German Jewish cultural education, and the impact of Yiddish theatre on German and Austrian Jews and on German theatre. They view German Jewish theatre activity through Jewish philosophical and critical perspectives and examine two important genres within which Jewish artists were particularly prominent: the Cabaret and Expressionist theatre. Finally, they provide close-ups of the Jewish artists Alexander Granach, Shimon Finkel, Max Reinhardt, and Leopold Jessner. By probing the interplay between “Jewish” and “German” cultural and cognitive identities based in the field of theatre and performance and querying the effect of theatre on Jewish self-understanding, they add to the richness of intercultural understanding as well as to the complex history of theatre and performance in Germany.

Studies of Eastern European literature have largely confined themselves to a single language, culture, or nationality. In this highly original book, Glaser shows how writers working in Russian, Ukrainian, and Yiddish during much of the nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth century were in intense conversation with one another. The marketplace was both the literal locale at which members of these different societies and cultures interacted with one another and a rich subject for representation in their art. It is commonplace to note the influence of Gogol on Russian literature, but Glaser shows him to have been a profound influence on Ukrainian and Yiddish literature as well. And she shows how Gogol must be understood not only within the context of his adopted city of St. Petersburg but also that of his native Ukraine. As Ukrainian and Yiddish literatures developed over this period, they were shaped by their geographical and cultural position on the margins of the Russian Empire. As distinctive as these writers may seem from one another, they are further illuminated by an appreciation of their common relationship to Russia. Glaser’s book paints a far more complicated portrait than scholars have traditionally allowed of Jewish (particularly Yiddish) literature in the context of Eastern European and Russian culture.

In Jihād in West Africa during the Age of Revolutions, a preeminent historian of Africa argues that scholars of the Americas and the Atlantic world have not given Africa its due consideration as part of either the Atlantic world or the age of revolutions. The book examines the jihād movement in the context of the age of revolutions—commonly associated with the American and French revolutions and the erosion of European imperialist powers—and shows how West Africa, too, experienced a period of profound political change in the late eighteenth through the mid-nineteenth centuries. Paul E. Lovejoy argues that West Africa was a vital actor in the Atlantic world and has wrongly been excluded from analyses of the period.

Among its chief contributions, the book reconceptualizes slavery. Lovejoy shows that during the decades in question, slavery expanded extensively not only in the southern United States, Cuba, and Brazil but also in the jihād states of West Africa. In particular, this expansion occurred in the Muslim states of the Sokoto Caliphate, Fuuta Jalon, and Fuuta Toro. At the same time, he offers new information on the role antislavery activity in West Africa played in the Atlantic slave trade and the African diaspora.

Finally, Jihād in West Africa during the Age of Revolutions provides unprecedented context for the political and cultural role of Islam in Africa—and of the concept of jihād in particular—from the eighteenth century into the present. Understanding that there is a long tradition of jihād in West Africa, Lovejoy argues, helps correct the current distortion in understanding the contemporary jihād movement in the Middle East, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Africa.

Jim Crow is the figure that has long represented America’s imperfect union. When the white actor Thomas D. Rice took to the stage in blackface as Jim Crow, during the 1830s, a ragged and charismatic trickster began channeling black folklore through American popular culture. This compact edition of the earliest Jim Crow plays and songs presents essential performances that assembled backtalk, banter, masquerade, and dance into the diagnostic American style. Quite contrary to Jim Crow’s reputation—which is to say, the term’s later meaning—these early acts undermine both racism and slavery. They celebrate an irresistibly attractive blackness in a young Republic that had failed to come together until Americans agreed to disagree over Jim Crow’s meaning.

As they permeated American popular culture, these distinctive themes formed a template which anticipated minstrel shows, vaudeville, ragtime, jazz, early talking film, and rock ‘n’ roll. They all show whites using rogue blackness to rehearse their mutual disaffection and uneven exclusion.

During his lifetime (1751–ca. 1840), English-born naturalist and artist John Abbot rendered more than 4,000 natural history illustrations and profoundly influenced North American entomology, as he documented many species in the New World long before they were scientifically described. For sixty-five years, Abbot worked in Georgia to advance knowledge of the flora and fauna of the American South by sending superbly mounted specimens and exquisitely detailed illustrations of insects, birds, butterflies, and moths, on commission, to collectors and scientists all over the world.

Between 1816 and 1818, Abbot completed 104 drawings of insects on their native plants for English naturalist and patron William Swainson (1789–1855). Both Abbot and Swainson were artists, naturalists, and collectors during a time when natural history and the sciences flourished. Separated by nearly forty years in age, Abbot and Swainson were members of the same international communities and correspondence networks upon which the study of nature was based during this period.

The relationship between these two men—who never met in person—is explored in John Abbot and William Swainson: Art, Science, and Commerce in Nineteenth-Century Natural History Illustration. This volume also showcases, for the first time, the complete set of original, full-color illustrations discovered in 1977 in the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington, New Zealand. Originally intended as a companion to an earlier survey of insects from Georgia, the newly rediscovered Turnbull manuscript presents beetles, grasshoppers, butterflies, moths, and a wasp. Most of the insects are pictured with the flowering plants upon which Abbot thought them to feed. Abbot’s journal annotations about the habits and biology of each species are also included, as are nomenclature updates for the insect taxa.

Today, the Turnbull drawings illuminate the complex array of personal and professional concerns that informed the field of natural history in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These illustrations are also treasured artifacts from times past, their far-flung travels revealing a world being reshaped by the forces of global commerce and information exchange even then. The shared project of John Abbot and William Swainson is now brought to completion, signaling the beginning of a new phase of its significance for modern readers and scholars.

Until 1860 John Ruskin's writings were primarily about art and architecture; but his belief that good art can flourish only in a society that is sound and healthy led him inevitably to a preoccupation with social and economic problems, the dominant concern of his later writings. James Clark Sherburne provides in this volume a detailed and long overdue re-examination of Ruskin's social and economic perceptions and, for the first time, systematically places these perceptions in their nineteenth-century intellectual context.

Ruskin's eloquence and the strength of his moral, aesthetic, and social convictions established him as one of the most influential of Victorian writers. His writings, however, are not easily categorized and many of his important insights occur as digressions in discussions of other topics. Mr. Sherburne succeeds in ordering and clarifying the rich chaos of Ruskin's social thought without denying that wholeness which is, paradoxically, its salient feature. He discovers the source of Ruskin's social criticism in his early writings. He then follows Ruskin's interest as it shifts from economic theory to the problems of exploitation, war, imperialism, the means of social reform, and the construction of the welfare state.

Ruskin's remarkably early vision of the possibility of economic abundance, his anticipation of its social and personal implications, his much disparaged critique of classical economics, his pioneering attention to the role of the consumer and the quality of consumption, his anxious portrayal of the effects of industrialism on the environment, his critique of English educational methods, and his farsighted proposals for public management of industry and transport are among the many aspects of Ruskin's thought examined by Mr. Sherburne. What emerges is an original and exhaustive study of a dimension of Ruskin's work which, though much neglected, is particularly relevant to contemporary concerns.

The contribution of Mill’s most authoritative biographer, Nicholas Capaldi, is a singular and unmatched highlight. The tenor of St. Augustine’s Press volumed on Mill is distinct in its intention to place his work in the framework of political philosophy and the conversation of the viability of liberalism as a tradition of thought.

Chopra shows how the European and Indian engineers, architects, and artists worked with each other to design a city—its infrastructure, architecture, public sculpture—that was literally constructed by Indian laborers and craftsmen. Beyond the built environment, Indian philanthropists entered into partnerships with the colonial regime to found and finance institutions for the general public. Too often thought to be the product of the singular vision of a founding colonial regime, British Bombay is revealed by Chopra as an expression of native traditions meshing in complex ways with European ideas of urban planning and progress.

The result, she argues, was the creation of a new shared landscape for Bombay’s citizens that ensured that neither the colonial government nor the native elite could entirely control the city’s future.

Murphy shows how Fisher, as pastor of the Congregational church in Blue Hill from 1796 to 1837, helped spearhead the transformation of a frontier settlement on the eastern shores of the Penobscot Bay into a thriving port community; how he used his skills as an architect, decorative painter, surveyor, and furniture maker not only to support himself and his family, but to promote the economic growth of his village; and how the fluid professional identity that enabled Fisher to prosper on the eastern frontier could only have existed in early America where economic relations were far less rigidly defined than in Europe.

Among the most important artifacts of Jonathan Fisher's life is the house he designed and built in Blue Hill. The Jonathan Fisher Memorial, as it is now known, serves as a point of departure for an examination of social, religious, and cultural life in a newly established village at the turn of the nineteenth century. Fisher's house provided a variety of spaces for agricultural and domestic work, teaching, socializing, artmaking, and more.

Through the eyes of Jonathan Fisher, we see his family grow and face the challenges of the new century, responding to religious, social, and economic change—sometimes succeeding and sometimes failing. We appreciate how an extraordinarily energetic man was able to capitalize on the wide array of opportunities offered by the frontier to give shape to his personal vision of community.

Winner of the David Woolley Evans and Beatrice Evans Biography Award and a History Book Club selection, 1985.

The core of Mormon belief was a conviction about actual events. The test of faith was not adherence to a certain confession of faith but belief that Christ was resurrected, that Joseph Smith saw God, that the Book of Mormon was true history, and that Peter, James, and John restored the apostleship. Mormonism was history, not philosophy.

It is as history that Richard L. Bushman analyzes the emergence of Mormonism in the early nineteenth century. Bushman, however, brings to his study a unique set of credentials--he is both a prize-winning historian and a faithful member of the Latter-day Saints church. For Mormons and non-Mormons alike, his book provides a very special perspective on an endlessly fascinating subject.

Building upon previous accounts and incorporating recently discovered contemporary sources, Bushman focuses on the first twenty-five years of Joseph Smith's life--up to his move to Kirtland, Ohio, in 1831. Bushman shows how the rural Yankee culture of New England and New York--especially evangelical revivalism, Christian rationalism, and folk magic--both influenced and hindered the formation of Smith's new religion.

Mormonism, Bushman argues, must be seen not only as the product of this culture, but also as an independent creation based on the revelations of its charismatic leader. In the final analysis, it was Smith's ability to breathe new life into the ancient sacred stories and to make a sacred story out of his own life which accounted for his own extraordinary influence. By presenting Smith and his revelations as they were viewed by the early Mormons themselves, Bushman leads us to a deeper understanding of their faith.

Preparations to initiate the first members of Joseph Smith’s Quorum of the Anointed, or Holy Order, as it was also known, were made on May 3, 1842. The walls of the second level of the Red Brick Store were painted with garden-themed murals, the rooms fitted with carpets, potted plants, and a veil hung from the ceiling. All the while, the ground level continued to operate as Joseph Smith’s general mercantile.

In this companion volume to The Nauvoo Endowment Companies and The Development of LDS Temple Worship, 1846-2000: A Documentary History, the editors have assembled all available primary references to the Anointed Quorum and its regular gatherings, both in the Red Brick Store and elsewhere (women were initially washed and anointed in Emma Smith’s bedroom and then escorted to the store) prior to the opening of the Nauvoo Temple. The sources include excerpts from the diaries of William Clayton, Joseph Fielding, Zina D. H. Jacobs, Heber C. Kimball, John Taylor, Willard Richards, George A. Smith, Joseph Smith, Wilford Woodruff, and Brigham Young; autobiographies and reminiscences by Joseph C. Kingsbury, George Miller, and Mercy Fielding Thompson; letters from Vilate Kimball and Lucius N. Scoville; the Manuscript History of Brigham Young; General Record of the Seventies, Book B; Bathsheba W. Smith’s unedited testimony from the 1892 Temple Lot Case; other manuscripts such as the Historian’s Office Journal and “Meetings of Anointed Quorum”; and published records such as the History of the Church, Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate and Times and Seasons.

from the jacket flap:

Despite the secrecy imposed upon members of the Anointed Quorum, word of the gatherings above Joseph Smith’s store soon spread. In one instance, housekeeper Maria Jane Johnston helped prepare the special ceremonial clothing for John Smith to wear at the group’s meetings. In another, Ebenezer Robinson innocently opened the upstairs door at the mercantile and was startled to see church apostle John Taylor in a long white robe and “turban,” carrying a sword. Only Nauvoo’s elite were invited to participate in these new ceremonies?never more than ninety individuals and even fewer during Joseph Smith’s lifetime?and, as the editors of the current volume write, only those who had been introduced to the prophet’s doctrine of plural marriage.

An unusual aspect of the Quorum of the Anointed, compared to the membership in the Nauvoo Masonic Lodge, was that women were initiated as regular members. However, the women effectively disappear after Brigham Young’s assumption of leadership in 1844, following Joseph Smith’s death, and remain virtually absent until the Nauvoo Temple is completed nearly a year and a half later. Readers will also note some of the differences in protocol between what Smith instigated and what Young eventually settled on, for instance that members could be washed and anointed repeatedly but were “endowed” only once. There were not yet proxy ordinances.

Among Latter-day Saints today, temple worship is a sensitive topic; but the editors of this volume do not reveal anything that would be considered invasive or indelicate. In fact, the accounts, which come almost exclusively from the early LDS leadership itself, manifest discretion about what to report.

Never before have these primary, authoritative sources been correlated by date for comparison and fuller understanding of the gradual development of the temple ceremonies. Readers may find an added benefit in discovering some of their own ancestors’ names included in these records; but in fact, anyone interested in LDS temple worship will find this compilation of primary documents to be invaluable.

The first full-length study of a significant figure of the Spanish Enlightenment

Latin American independence histories of the last 150 years have tended to stereotype Captain General Bustamante, governor of the Spanish colony of Guatemala from 1811 to 1818, as a tyrannical arch-villain who personified colonial oppression. Timothy Hawkins, in contrast, examines Bustamante and his administration within the context of preservation of empire, the effort by colonial officials and partisans to maintain the integrity of the Spanish empire in spite of internal and external unrest.

Based on extensive primary research in the archives of Guatemala, Mexico, and Spain, Hawkins’s approach links the Central American experience to that of areas such as Peru, Venezuela, and Mexico, that also responded equivocally and haphazardly to rebellious uprisings against colonial rule. While conceding that Bustamante’s role in the suppression of unrest turned him into one of the more controversial figures in Latin American history, Hawkins argues that the Bustamante administration should not be seen as an isolated and perverse case of Spanish repression but as an example of a relatively successful, if short lived, campaign by Spain to preserve its empire.

A Cuban exile from 1881 to 1895, Martí was a correspondent writing in New York for various Latin American newspapers. Grasping the significance of rising U.S. imperial power, he came to understand the Americas as a complex system of kindred—but not equal—national formations whose cultural and political integrity was threatened by the overbearing aggressiveness of the United States. This collection explores how in his journalistic work Martí critiques U.S. racism, imperialism, and capitalism; warns Latin America of impending U.S. geographical, cultural, and economic annexation; and calls for recognition of the diversity of America’s cultural voices. Reinforcing Martí’s hemispheric vision with essays by a wide range of scholars who investigate his analysis of the United States, his significance as a Latino outsider, and his analyses of Latin American cultural politics, this volume explores the affinities between Martí’s thought and current reexaminations of what it means to study America.

José Martí’s Our America offers a new understanding of Martí’s ambiguous and problematic relation with the United States and will engage scholars and students in American, Latin American, and Latino studies as well as those interested in cultural, postcolonial, gender, and ethnic studies.

Contributors. Jeffrey Belnap, Raúl Fernández, Ada Ferrer, Susan Gillman, George Lipsitz, Oscar Martí, David Noble, Donald E. Pease, Beatrice Pita, Brenda Gayle Plummer, Susana Rotker, José David Saldívar, Rosaura Sánchez, Enrico Mario Santí, Doris Sommer, Brook Thomas

White publishers and editors used their newspapers to build, nurture, and protect white supremacy across the South in the decades after the Civil War. At the same time, a vibrant Black press fought to disrupt these efforts and force the United States to live up to its democratic ideals. Journalism and Jim Crow centers the press as a crucial political actor shaping the rise of the Jim Crow South. The contributors explore the leading role of the white press in constructing an anti-democratic society by promoting and supporting not only lynching and convict labor but also coordinated campaigns of violence and fraud that disenfranchised Black voters. They also examine the Black press’s parallel fight for a multiracial democracy of equality, justice, and opportunity for all—a losing battle with tragic consequences for the American experiment.

Original and revelatory, Journalism and Jim Crow opens up new ways of thinking about the complicated relationship between journalism and power in American democracy.

Contributors: Sid Bedingfield, Bryan Bowman, W. Fitzhugh Brundage, Kathy Roberts Forde, Robert Greene II, Kristin L. Gustafson, D'Weston Haywood, Blair LM Kelley, and Razvan Sibii

The editors supply full annotations of Melville's allusions and terse entries and an exhaustive index makes available the range of his acquaintance with people, places, and works of art. Also included are related documents, illustrations, maps, and many pages and passages reproduced from the journals. This scholarly edition aims to present a text as close to the author's intention as his difficult handwriting permits. It is an Approved Text of the Center for Editions of American Authors (Modern Language Association of America).

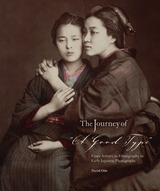

When Japan opened its doors to the West in the 1860s, delicately hand-tinted photographic prints of Japanese people and landscapes were among its earliest and most popular exports. Renowned European photographers Raimund von Stillfried and Felice Beato established studios in Japan in the 1860s; the work was soon taken up by their Japanese protégés and successors Uchida Kuichi, Kusakabe Kimbei, and others. Hundreds of these photographs, collected by travelers from the Boston area, were eventually donated to Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, where they were archived for their ethnographic content and as scientific evidence of an "exotic" culture.

In this elegant volume, visual anthropologist David Odo examines the Peabody’s collection of Japanese photographs and the ways in which such objects were produced, acquired, and circulated in the nineteenth century. His innovative study reveals the images' shifting and contingent uses—from tourist souvenir to fine art print to anthropological “type” record—were framed by the desires and cultural preconceptions of makers and consumers alike. Understood as both images and objects, the prints embody complex issues of history, culture, representation, and exchange.

Contributions by Egor Kovalevsky, Anna Aslanyan, Sergey Glebov, David Schimmelpenninck, Mukaram Hhana, and Michal Wasiucionek

Juana Briones was born in 1802 and spent her early youth in Santa Cruz, a community of retired soldiers who had helped found Spanish California, Native Americans, and settlers from Mexico. In 1820, she married a cavalryman at the San Francisco Presidio, Apolinario Miranda. She raised her seven surviving sons and daughters and adopted an orphaned Native American girl. Drawing on knowledge she gained about herbal medicine and other cures from her family and Native Americans, she became a highly respected curandera, or healer.

Juana set up a second home and dairy at the base of then Loma Alta, now Telegraph Hill, the first house in that area. After gaining a church-sanctioned separation from her abusive husband, she expanded her farming and cattle business in 1844 by purchasing a 4,400-acre ranch, where she built her house, located in the present city of Palo Alto. She successfully managed her extensive business interests until her death in 1889. Juana Briones witnessed extraordinary changes during her lifetime. In this fascinating book, readers will see California’s history in a new and revelatory light.

Amid an air of stalemate, the Confederates planned a bold move to strike at Washington, DC and capture or scatter Lincoln and his cabinet. In command of the operation was the colorful and unpredictable Jubal “Old Jube” Anderson Early, brought in to replace the fallen Stonewall Jackson. Less well known than the bloodier Antietam and Gettysburg, Early's campaign, Cooling argues, had greater significance.

In addition to the persnickety bachelor Anderson, this account introduces many colorful participants, including railroad president John W. Garrett, the politically influential Blair family, and Elizabeth “Aunt Betty” Thomas, a free Black woman, who was said to have saved Lincoln’s life by shouting at him: “Get down, you fool!” when he came under fire at Fort Stevens. Exciting and comprehensive, Civil War scholars and readers will delight in this masterful account.

This book investigates the political and public standing of the Supreme Court following the Dred Scott decision. Arguing against interpretations by previous historians, Kutler asserts instead that the "Chase Court" was neither enfeebled by the decision itself, nor by congressional Republicans during reconstruction. Instead, Kutler suggests that during reconstruction, the Court was characterized by forcefulness and judicious restraint rather than timidity and cowardice, holding a creative and determining role rather than abdicating its rightful powers. This volume assembles a series of essays by Kutler arguing for this characterization. Provocative and persuasive at turns, this collection of essays provides a bold and innovative reinterpretation of the Supreme Court after the Civil War.

Julian Hawthorne (1846-1934), Nathaniel Hawthorne's only son, lived a long and influential life marked by bad circumstances and worse choices. Raised among luminaries such as Thoreau, Emerson, and the Beecher family, Julian became a promising novelist in his twenties, but his writing soon devolved into mediocrity.

What talent the young Hawthorne had was spent chasing across the changing literary and publishing landscapes of the period in search of a paycheck, writing everything from potboilers to ad copy. Julian was consistently short of funds because--as biographer Gary Scharnhorst is the first to reveal--he was supporting two households: his wife in one and a longtime mistress in the other.

The younger Hawthorne's name and work ethic gave him influence in spite of his haphazard writing. Julian helped to found Cosmopolitan and Collier's Weekly. As a Hearst stringer, he covered some of the era's most important events: McKinley's assassination, the Galveston hurricane, and the Spanish-American War, among others.

When Julian died at age 87, he had written millions of words and more than 3,000 pieces, out-publishing his father by a ratio of twenty to one. Gary Scharnhorst, after his own long career including works on Mark Twain, Oscar Wilde, and other famous writers, became fascinated by the leaps and falls of Julian Hawthorne. This biography shows why.

Beginning in the 1830s, the white actor Thomas D. Rice took to the stage as Jim Crow, and the ragged and charismatic trickster of black folklore entered—and forever transformed—American popular culture. Jump Jim Crow brings together for the first time the plays and songs performed in this guise and reveals how these texts code the complex use and abuse of blackness that has characterized American culture ever since Jim Crow’s first appearance.

Along with the prompt scripts of nine plays performed by Rice—never before published as their original audiences saw them—W. T. Lhamon, Jr., provides a reconstruction of their performance history and a provocative analysis of their contemporary meaning. His reading shows us how these plays built a public blackness, but also how they engaged a disaffected white audience, who found in Jim Crow’s sass and wit and madcap dancing an expression of rebellion and resistance against the oppression and confinement suffered by ordinary people of all colors in antebellum America and early Victorian England.

Upstaging conventional stories and forms, giving direction and expression to the unruly attitudes of a burgeoning underclass, the plays in this anthology enact a vital force still felt in great fictions, movies, and musics of the Atlantic and in the jumping, speedy styles that join all these forms.

Gillian M. Rodger uses the development of male impersonation from the early nineteenth century to the early twentieth century to illuminate the history of the variety show. Exploding notions of high- and lowbrow entertainment, Rodger looks at how both performers and forms consistently expanded upward toward respectable—and richer—audiences. At the same time, she illuminates a lost theatrical world where women made fun of middle-class restrictions even as they bumped up against rules imposed in part by audiences. Onstage, the actresses' changing performance styles reflected gender construction in the working class and shifts in class affiliation by parts of the audiences. Rodger observes how restrictive standards of femininity increasingly bound male impersonators as new gender constructions allowed women greater access to public space while tolerating less independent behavior from them.

The Arab Spring uprisings of 2011 were often portrayed in the media as a dawn of democracy in the region. But the revolutionaries were—and saw themselves as—heirs to a centuries-long struggle for just government and the rule of law, a struggle obstructed by local elites as well as the interventions of foreign powers. Elizabeth F. Thompson uncovers the deep roots of liberal constitutionalism in the Middle East through the remarkable stories of those who fought against poverty, tyranny, and foreign rule.

Fascinating, sometimes quixotic personalities come to light: Tanyus Shahin, the Lebanese blacksmith who founded a peasant republic in 1858; Halide Edib, the feminist novelist who played a prominent role in the 1908 Ottoman constitutional revolution; Ali Shariati, the history professor who helped ignite the 1979 Iranian Revolution; Wael Ghonim, the Google executive who rallied Egyptians to Tahrir Square in 2011, and many more. Their memoirs, speeches, and letters chart the complex lineage of political idealism, reform, and violence that informs today’s Middle East.

Often depicted as inherently anti-democratic, Islam was integral to egalitarian movements that sought to correct imbalances of power and wealth wrought by the modern global economy—and by global war. Motivated by a memory of betrayal at the hands of the Great Powers after World War I and in the Cold War, today’s progressives assert a local tradition of liberal constitutionalism that has often been stifled but never extinguished.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press