In eighteenth-century America, the East was, paradoxically, a means of reinforcing the enlightenment values of the West: Franklin, Jefferson, and other American writers found in Confucius a complement to their own political and philosophical beliefs. In the nineteenth century, with the shift from an agrarian to an industrial economy, the Hindu Orient emerged as a mystical alternative to American reality. During this period, Emerson, Thoreau, and other Transcendentalists viewed the "Oriental" not as an exotic other but as an image of what Americans could be, if stripped of all the commercialism and materialism that set them apart from their ideal. A similar sense of Oriental otherness informed the aesthetic discoveries of the early twentieth century, as Pound, Eliot, and other poets found in Chinese and Japanese literature an artistic purity and intensity absent from Western tradition. For all of these figures the Orient became a complex fantasy that allowed them to overcome something objectionable, either in themselves or in the culture of which they were a part, in order to attain some freer, more genuine form of philosophical, religious, or artistic expression.

Drawing on archival sources and fieldwork, the contributors explore aspects of modernity within societies of South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. Whether considering how European ideas of Orientalism became foundational myths of Indian nationalism; how racial caste systems between blacks, South Asians, and whites operate in post-apartheid South Africa; or how Indian immigrants to the United States negotiate their identities, these essays demonstrate that the contours of cultural and identity politics did not simply originate in metropolitan centers and get adopted wholesale in the colonies. Colonial and postcolonial modernisms have emerged via the active appropriation of, or resistance to, far-reaching European ideas. Over time, Orientalism and nationalist and racialized knowledges become indigenized and acquire, for all practical purposes, a completely "Third World" patina. Antinomies of Modernity shows that people do make history, constrained in part by political-economic realities and in part by the categories they marshal in doing so.

Contributors. Neville Alexander, Andrew Barnes, Vasant Kaiwar, Sucheta Mazumdar, Minoo Moallem, Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi, A. R. Venkatachalapathy, Michael O. West

Through readings of Flaubert, Nerval, Kipling, Blunt, and Eberhardt, and following the transition in travel literature from travelog to tourist guide, Belated Travelers addresses the specific historical conditions of late nineteenth-century orientalism implicated in the discourses of desire and power. Behdad also views a broad range of issues in addition to nostalgia and tourism, including transvestism and melancholia, to specifically demonstrate the ways in which the heterogeneity of orientalism and the plurality of its practice is an enabling force in the production and transformation of colonial power.

An exceptional work that provides an important critique of issues at the forefront of critical practice today, Belated Travelers will be eagerly awaited by specialists in nineteenth-century British and French literatures, and all concerned with colonial and post-colonial discourse.

A polemical analysis of the ways Orientalism speaks through the texts of prominent Asian American writers.

Asian American resistance to Orientalism—the Western tradition dealing with the subject and subjugation of the East—is usually assumed. And yet, as this provocative work demonstrates, in order to refute racist stereotypes they must first be evoked, and in the process the two often become entangled. Sheng-mei Ma shows how the distinguished careers of post-1960s Asian American writers such as Maxine Hong Kingston, Amy Tan, Frank Chin, and David Henry Hwang reveal that while Asian American identity is constructed in reaction to Orientalism, the two cultural forces are not necessarily at odds. The vigor with which these Asian Americans revolt against Orientalism in fact tacitly acknowledges the family lineage of the two.

To identify the multitude of historical forms appropriated by the deathly embrace of Orientalism and Asian American ethnicity, Ma highlights four types of cultural encounters, embodied in four metaphors of physical states: the "clutch of rape" in imperialist adventure narratives of the 1930s and 1940s, as seen in comic strips of Flash Gordon and Terry and the Pirates and in the Disney film Swiss Family Robinson; the "clash of arms" or martial metaphors in the 1970s and beyond, embodied in Bruce Lee, Kingston’s The Woman Warrior, and the video game Mortal Kombat; U.S. multicultural "flaunting" of ethnicity in the work of Amy Tan and in Disney’s Mulan; and global postcolonial "masquerading" of ethnicity in the Anglo-Japanese novelist Kazuo Ishiguro.Broad in scope, penetrating in insight, Ma’s work exposes the myriad ways in which Orientalism, an integral part of American culture, speaks through the texts of Asian Americans and non–Asian Americans alike. The result is a startling lesson in the construction of cultural identity.

The Sheik—E. M. Hull’s best-selling novel that became a wildly popular film starring Rudolph Valentino—kindled “sheik fever” across the Western world in the 1920s. A craze for all things romantically “Oriental” swept through fashion, film, and literature, spawning imitations and parodies without number. While that fervor has largely subsided, tales of passion between Western women and Arab men continue to enthrall readers of today’s mass-market romance novels. In this groundbreaking cultural history, Hsu-Ming Teo traces the literary lineage of these desert romances and historical bodice rippers from the twelfth to the twenty-first century and explores the gendered cultural and political purposes that they have served at various historical moments.

Drawing on “high” literature, erotica, and popular romance fiction and films, Teo examines the changing meanings of Orientalist tropes such as crusades and conversion, abduction by Barbary pirates, sexual slavery, the fear of renegades, the Oriental despot and his harem, the figure of the powerful Western concubine, and fantasies of escape from the harem. She analyzes the impact of imperialism, decolonization, sexual liberation, feminism, and American involvement in the Middle East on women’s Orientalist fiction. Teo suggests that the rise of female-authored romance novels dramatically transformed the nature of Orientalism because it feminized the discourse; made white women central as producers, consumers, and imagined actors; and revised, reversed, or collapsed the binaries inherent in traditional analyses of Orientalism.

In the absence of specialized programs of study, abstract discussions of China in Latin America took shape in contingent critical infrastructures built at the crossroads of the literary market, cultural diplomacy, and commerce. As Rosario Hubert reveals, modernism flourishes comparatively, in contexts where cultural criticism is a creative and cosmopolitan practice.

Disoriented Disciplines: China, Latin America, and the Shape of World Literature understands translation as a material act of transfer, decentering the authority of the text and connecting seemingly untranslatable cultural traditions. In this book, chinoiserie, “coolie” testimonies, Maoist prints, visual poetry, and Cold War memoirs compose a massive archive of primary sources that cannot be read or deciphered with the conventional tools of literary criticism. As Hubert demonstrates, even canonical Latin American authors, including Jorge Luis Borges, Octavio Paz, and Haroldo de Campos, write about China from the edges of philology, mediating the concrete as well as the sensorial.

Advocating for indiscipline as a core method of comparative literary studies, Disoriented Disciplines challenges us to interrogate the traditional contours of the archives and approaches that define the geopolitics of knowledge.

Srinivas Aravamudan here reveals how Oriental tales, pseudo-ethnographies, sexual fantasies, and political satires took Europe by storm during the eighteenth century. Naming this body of fiction Enlightenment Orientalism, he poses a range of urgent questions that uncovers the interdependence of Oriental tales and domestic fiction, thereby challenging standard scholarly narratives about the rise of the novel.

When Portuguese explorers first rounded the Cape of Good Hope and arrived in the subcontinent in the late fifteenth century, Europeans had little direct knowledge of India. The maritime passage opened new opportunities for exchange of goods as well as ideas. Traders were joined by ambassadors, missionaries, soldiers, and scholars from Portugal, England, Holland, France, Italy, and Germany, all hoping to learn about India for reasons as varied as their particular nationalities and professions. In the following centuries they produced a body of knowledge about India that significantly shaped European thought.

Europe’s India tracks Europeans’ changing ideas of India over the entire early modern period. Sanjay Subrahmanyam brings his expertise and erudition to bear in exploring the connection between European representations of India and the fascination with collecting Indian texts and objects that took root in the sixteenth century. European notions of India’s history, geography, politics, and religion were strongly shaped by the manuscripts, paintings, and artifacts—both precious and prosaic—that found their way into Western hands.

Subrahmanyam rejects the opposition between “true” knowledge of India and the self-serving fantasies of European Orientalists. Instead, he shows how knowledge must always be understood in relation to the concrete circumstances of its production. Europe’s India is as much about how the East came to be understood by the West as it is about how India shaped Europe’s ideas concerning art, language, religion, and commerce.

Against this xenophobic tendency, The Feeling of History examines the idea of Andalucismo—a modern tradition founded on the principle that contemporary Andalusia is connected in vitally important ways with medieval Islamic Iberia. Charles Hirschkind explores the works and lives of writers, thinkers, poets, artists, and activists, and he shows how, taken together, they constitute an Andalusian sensorium. Hirschkind also carefully traces the various itineraries of Andalucismo, from colonial and anticolonial efforts to contemporary movements supporting immigrant rights. The Feeling of History offers a nuanced view into the way people experience their own past, while also bearing witness to a philosophy of engaging the Middle East that experiments with alternative futures.

-Russell Berman, Stanford University

"Intellectually rigorous and conceptually nuanced, Todd Kontje's German Orientalisms is a valuable contribution to the debate on identity politics in German cultural history. Through an erudite and insightful analysis of the German fictions of a broadly defined 'Orient' from the Middle Ages to the present, Kontje illustrates how German literature situated itself within a 'symbolic geography,' whose coordinates are defined by both its representations of the Orient and its affiliation with the Occident. German Orientalisms offers not only an admirable synthesis of the scholarship on German linguistic and cultural nationalism but also sophisticated interpretive strategies for a better understanding of our perceptions and misconceptions of alterity."

-Azade Seyhan, Bryn Mawr College

"This is a fascinating topic, and the book opens new scholarly vistas. In an age of increased specialization, Kontje takes a macro view, looking at German literature almost

from its beginnings to the present, from Wolfram to Özdamar. He also has the courage to link his well-researched work to topics like globalization, the culture wars, and canon formation. He doesn't merely proclaim literature's importance, he shows by example how the literary imagination-creative as it is, dodging dogmatism, and able to confound ideologies-can thrive in an era of cultural studies."

-Sara Friedrichsmeyer, University of Cincinnati

Todd Kontje's German Orientalisms offers a fresh examination of the role of the East in German literary imagination, ranging from the Middle Ages to the present. In its wide historical sweep, this book offers important new insights into many of the most famous writers in the German language, from Goethe to Thomas Mann to Günter Grass.

Building on Edward Said's Orientalism-which defined Orientalism as a form of Western knowledge directly linked to imperial power-Kontje offers a more nuanced version as seen through the lens of German literature of the last thousand years.

Said's focus was on British and French Orientalists-two nations with colonial interests in the East. Germany was different in that it had no stake in the Orient. Far from diminishing an Orientalist perspective, however, the absence of a German empire in the East produced a peculiarly German brand of Orientalism, one in which German writers alternated between identification with the rest of Europe and allying themselves with parts of the East against the West.

Above all, Kontje asks how German writers conceived of their place in "the land of the center" (das Land der Mitte) and how their literary works help to create the imagined community of the German nation.

Transference of orientalist images and identities to the American landscape and its inhabitants, especially in the West—in other words, portrayal of the West as the “Orient”—has been a common aspect of American cultural history. Place names, such as the Jordan River or Pyramid Lake, offer notable examples, but the imagery and its varied meanings are more widespread and significant. Understanding that range and significance, especially to the western part of the continent, means coming to terms with the complicated, nuanced ideas of the Orient and of the North American continent that European Americans brought to the West. Such complexity is what historical geographer Richard Francaviglia unravels in this book.

Since the publication of Edward Said’s book, Orientalism, the term has come to signify something one-dimensionally negative. In essence, the orientalist vision was an ethnocentric characterization of the peoples of Asia (and Africa and the “Near East”) as exotic, primitive “others” subject to conquest by the nations of Europe. That now well-established point, which expresses a postcolonial perspective, is critical, but Francaviglia suggest that it overlooks much variation and complexity in the views of historical actors and writers, many of whom thought of western places in terms of an idealized and romanticized Orient. It likewise neglects positive images and interpretations to focus on those of a decadent and ostensibly inferior East.

We cannot understand well or fully what the pervasive orientalism found in western cultural history meant, says Francaviglia, if we focus only on its role as an intellectual engine for European imperialism. It did play that role as well in the American West. One only need think about characterizations of American Indians as Bedouins of the Plains destined for displacement by a settled frontier. Other roles for orientalism, though, from romantic to commercial ones, were also widely in play. In Go East, Young Man, Francaviglia explores a broad range of orientalist images deployed in the context of European settlement of the American West, and he unfolds their multiple significances.

A seventeenth-century English traveler to the Eastern Mediterranean would have faced a problem in writing about this unfamiliar place: how to describe its inhabitants in a way his countrymen would understand? In an age when a European education meant mastering the Classical literature of Greece and Rome, he would naturally turn to touchstones like the Iliad to explain the exotic customs of Ottoman lands. His Turk would have been Homer’s Turk.

An account of epic sweep, spanning the Crusades, the Indian Raj, and the postwar decline of the British Empire, Homer’s Turk illuminates how English writers of all eras have relied on the Classics to help them understand the world once called “the Orient.” Ancient Greek and Roman authors, Jerry Toner shows, served as a conceptual frame of reference over long periods in which trade, religious missions, and imperial interests shaped English encounters with the East. Rivaling the Bible as a widespread, flexible vehicle of Western thought, the Classics provided a ready model for portrayal and understanding of the Oriental Other. Such image-making, Toner argues, persists today in some of the ways the West frames its relationship with the Islamic world and the rising powers of India and China.

Discussing examples that range from Jacobean travelogues to Hollywood blockbusters, Homer’s Turk proves that there is no permanent version of either the ancient past or the East in English writing—the two have been continually reinvented alongside each other.

Joseph Massad’s Islam in Liberalism explores what Islam has become in today’s world, with full attention to the multiplication of its meanings and interpretations. He seeks to understand how anxieties about tyranny, intolerance, misogyny, and homophobia, seen in the politics of the Middle East, are projected onto Islam itself. Massad shows that through this projection Europe emerges as democratic and tolerant, feminist, and pro-LGBT rights—or, in short, Islam-free. Massad documents the Christian and liberal idea that we should missionize democracy, women’s rights, sexual rights, tolerance, equality, and even therapies to cure Muslims of their un-European, un-Christian, and illiberal ways. Along the way he sheds light on a variety of controversial topics, including the meanings of democracy—and the ideological assumption that Islam is not compatible with it while Christianity is—women in Islam, sexuality and sexual freedom, and the idea of Abrahamic religions valorizing an interfaith agenda. Islam in Liberalism is an unflinching critique of Western assumptions and of the liberalism that Europe and Euro-America blindly present as a type of salvation to an assumingly unenlightened Islam.

With the untimely death of Edward W. Said in 2003, various academic and public intellectuals worldwide have begun to reassess the writings of this powerful oppositional intellectual. Figures on the neoconservative right have already begun to discredit Said’s work as that of a subversive intent on slandering America’s benign global image and undermining its global authority. On the left, a significant number of oppositional intellectuals are eager to counter this neoconservative vilification, proffering a Said who, in marked opposition to the “anti-humanism” of the great poststructuralist thinkers who were his contemporaries--Jacques Derrida, Jean-Francois Lyotard, Jacques Lacan, Louis Althusser, and Michel Foucault--reaffirms humanism and thus rejects poststructuralist theory.

In this provocative assessment of Edward Said’s lifework, William V. Spanos argues that Said’s lifelong anti-imperialist project is actually a fulfillment of the revolutionary possibilities of poststructuralist theory. Spanos examines Said, his legacy, and the various texts he wrote--including Orientalism,Culture and Imperialism, and Humanism and Democratic Criticism--that are now being considered for their lasting political impact.

Since the Cold War ended, China has become a global symbol of disregard for human rights, while the United States has positioned itself as the world’s chief exporter of the rule of law. How did lawlessness become an axiom about Chineseness rather than a fact needing to be verified empirically, and how did the United States assume the mantle of law’s universal appeal? In a series of wide-ranging inquiries, Teemu Ruskola investigates the history of “legal Orientalism”: a set of globally circulating narratives about what law is and who has it. For example, why is China said not to have a history of corporate law, as a way of explaining its “failure” to develop capitalism on its own? Ruskola shows how a European tradition of philosophical prejudices about Chinese law developed into a distinctively American ideology of empire, influential to this day.

The first Sino-U.S. treaty in 1844 authorized the extraterritorial application of American law in a putatively lawless China. A kind of legal imperialism, this practice long predated U.S. territorial colonialism after the Spanish-American War in 1898, and found its fullest expression in an American district court’s jurisdiction over the “District of China.” With urgent contemporary implications, legal Orientalism lives on in the enduring damage wrought on the U.S. Constitution by late nineteenth-century anti-Chinese immigration laws, and in the self-Orientalizing reforms of Chinese law today. In the global politics of trade and human rights, legal Orientalism continues to shape modern subjectivities, institutions, and geopolitics in powerful and unacknowledged ways.

The Limits of Orientalism: Seventeenth-Century Representations of India challenges the recent postcolonial readings of European, predominantly English, representations of India in the seventeenth century. Following Edward Said’s discourse of “Orientalism,” most postcolonial analyses of the seventeenth-century representations of India argue that the natives are represented as barbaric or exotic “others,” imagining these representations as products of colonial ideology. Such approaches tend to offer a homogeneous idea of the “native” and usually equate it with the term “Indian.” Sapra, however, argues that instead of representing all natives as barbaric “others,” the English drew parallels, especially between themselves and the Mughal aristocracy, associating with them as partners in trade and potential allies in war. While the Muslims are from the outset largely portrayed as highly civilized and cultured, early European writers tended to be more conflicted with Hindus, their first highly negative views undergoing a transformation that brings into question any straightforward Orientalist reading of the texts and anticipates the complexity of later representations of the indigenous peoples of the sub-continent.

Sapra’s theoretical and methodological approach is influenced by such writers as Aijaz Ahmad and Denis Porter, who have highlighted powerful alternatives to Said’s discourse of “Orientalism.” Sapra historicizes European representations of the indigenous to draw attention to the contrasting approaches of the Portuguese, the Dutch and the English in relation to seventeenth-century India, effectively undermining comfortable notions of a homogenous “West.” Unlike the Portuguese, for whom the idea of a dynasty and the conversion of heathens went hand in hand with the idea of trade, for the Dutch and the English the primary consideration was commercial. In keeping with the commercial approach of the English East India Company, most English travelers, instead of representing the Muslims as barbaric “others,” highlight the compatibility between the two cultures and consistently praise the Mughal empire for its religious tolerance. In the representations of the Hindus, Sapra demonstrates that most writers, even while denigrating the Hindu religion, appreciate the civilized society of the Hindus. Moreover, in the representations of sati or widow-burning, a distinction needs to be made between the patriarchal and the Orientalist points of views, which are at variance with each other. The tension between the patriarchal and the Orientalist positions challenges Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s analysis of sati in “Can the Subaltern Speak?” which has become the standard model for most postcolonial appraisals of European representations of sati. The book highlights the lacuna in postcolonial readings by providing access to selections of commonly unavailable early-modern writings by Thomas Roe, Edward Terry, Henry Lord, Thomas Coryate, Alexander Hamilton and other the records of the East India Company, which makes the book vital for students of theory, European and South-Asian history, and Renaissance literatures.

Published by University of Delaware Press. Distributed worldwide by Rutgers University Press.

Edwards reads a broad range of texts to recuperate the disorienting possibilities for rethinking American empire. Examining work by William Burroughs, Jane Bowles, Ernie Pyle, A. J. Liebling, Jane Kramer, Alfred Hitchcock, Clifford Geertz, James Michener, Ornette Coleman, General George S. Patton, and others, he puts American texts in conversation with an archive of Maghrebi responses. Whether considering Warner Brothers’ marketing of the movie Casablanca in 1942, journalistic representations of Tangier as a city of excess and queerness, Paul Bowles’s collaboration with the Moroccan artist Mohammed Mrabet, the hippie communities in and around Marrakech in the 1960s and early 1970s, or the writings of young American anthropologists working nearby at the same time, Edwards illuminates the circulation of American texts, their relationship to Maghrebi history, and the ways they might be read so as to reimagine the role of American culture in the world.

Shimakawa looks at the origins of Asian American theater, particularly through the memories of some of its pioneers. Her examination of the emergence of Asian American theater companies illuminates their strategies for countering the stereotypes of Asian Americans and the lack of visibility of Asian American performers within the theater world. She shows how some plays—Wakako Yamauchi’s 12-1-A, Frank Chin’s Chickencoop Chinaman, and The Year of the Dragon—have both directly and indirectly addressed the displacement of Asian Americans. She analyzes works attempting to negate the process of abjection—such as the 1988 Broadway production of M. Butterfly as well as Miss Saigon, a mainstream production that enacted the process of cultural displacement both onstage and off. Finally, Shimakawa considers Asian Americanness in the context of globalization by meditating on the work of Ping Chong, particularly his East-West Quartet.

This study examines the history of Zionist academic Orientalism—referred to throughout as Oriental studies, the term contemporary English speakers would have used—in light of its German-Jewish background, as a history of knowledge transfer stretching along an axis from Germany to Palestine. The transfer, which took place primarily during the 1920s and 1930s, involved questions about the re-establishment, far from Germany, of a field of knowledge with deep German roots. Like other German-Jewish scholars arriving in Palestine at the time, some of the Orientalist agents of transfer did so out of Zionist conviction as olim (immigrants making aliyah, or literally “ascending” to the homeland), while others joined them later as refugees from Nazi Germany; both groups were integrated into the institutional apparatus of the Hebrew University. Unlike other fields of knowledge or professions, however, the transfer of Orientalist knowledge was unique in that the axis involved an essential change in the nature of its encounter with the Orient: from a textual-scientific encounter at German universities, largely disconnected from contemporary issues to a living, substantive, and unmediated encounter with an essentially Arab region—and the escalating Jewish-Arab conflict in the background. Within the new context, German-Jewish Orientalist expertise was charged with political and cultural significance it had not previously faced, fundamentally influencing the course of the discipline’s development in Palestine and Israel.

Consulting rare and unpublished materials, Qian traces Pound’s and Williams’s remarkable dialogues with the great Chinese poets—Qu Yuan, Li Bo, Wang Wei, and Bo Juyi—between 1913 and 1923. His investigation reveals that these exchanges contributed more than topical and thematic ideas to the Americans’ work and suggests that their progressively modernist style is directly linked to a steadily growing contact and affinity for similar Chinese styles. He demonstrates, for example, how such influences as the ethics of pictorial representation, the style of ellipsis, allusion, and juxtaposition, and the Taoist/Zen–Buddhist notion of nonbeing/being made their way into Pound’s pre-Fenollosan Chinese adaptations, Cathay, Lustra, and the Early Cantos, as well as Williams’s Sour Grapes and Spring and All. Developing a new interpretation of important work by Pound and Williams, Orientalism and Modernism fills a significant gap in accounts of American Modernism, which can be seen here for the first time in its truly multicultural character.

Looking at the political significance of cross-cultural encounters refracted through the visual languages of Orientalism, the contributors engage with pressing recent debates about indigenous agency, postcolonial identity, and gendered subjectivities. The very range of artists, styles, and forms discussed in this collection broadens contemporary understandings of Orientalist art. Among the artists considered are the Algerian painters Azouaou Mammeri and Mohammed Racim; Turkish painter Osman Hamdi; British landscape painter Barbara Bodichon; and the French painter Henri Regnault. From the liminal "Third Space" created by mosques in postcolonial Britain to the ways nineteenth-century harem women negotiated their portraits by British artists, the essays in this collection force a rethinking of the Orientalist canon.

This innovative volume will appeal to those interested in art history, theories of gender, and postcolonial studies.

Contributors. Jill Beaulieu, Roger Benjamin, Zeynep Çelik, Deborah Cherry, Hollis Clayson, Mark Crinson, Mary Roberts

The writings of a small group of scholars known as the ilustrados are often credited for providing intellectual grounding for the Philippine Revolution of 1896. Megan C. Thomas shows that the ilustrados’ anticolonial project of defining and constructing the “Filipino” involved Orientalist and racialist discourses that are usually ascribed to colonial projects, not anticolonial ones. According to Thomas, the work of the ilustrados uncovers the surprisingly blurry boundary between nationalist and colonialist thought.

By any measure, there was an extraordinary flowering of scholarly writing about the peoples and history of the Philippines in the decade or so preceding the revolution. In reexamining the works of the scholars José Rizal, Pardo de Tavera, Isabelo de los Reyes, Pedro Paterno, Pedro Serrano Laktaw, and Mariano Ponce, Thomas situates their writings in a broader account of intellectual ideas and politics migrating and transmuting across borders. She reveals how the ilustrados both drew from and refashioned the tools and concepts of Orientalist scholarship from Europe.

Interrogating the terms “nationalist” and “nationalism,” whose definitions are usually constructed in the present and then applied to the past, Thomas offers new models for studying nationalist thought in the colonial world.

From the Biblical period and Classical Antiquity to the rise of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, aspects of Persian culture have been integral to European history. A diverse constellation of European artists, poets, and thinkers have looked to Persia for inspiration, finding there a rich cultural counterpoint and frame of reference. Interest in all things Persian was no passing fancy but an enduring fascination that has shaped not just Western views but the self-image of Iranians up to the present day. Persophilia maps the changing geography of connections between Persia and the West over the centuries and shows that traffic in ideas about Persia and Persians did not travel on a one-way street.

How did Iranians respond when they saw themselves reflected in Western mirrors? Expanding on Jürgen Habermas’s theory of the public sphere, and overcoming the limits of Edward Said, Hamid Dabashi answers this critical question by tracing the formation of a civic discursive space in Iran, seeing it as a prime example of a modern nation-state emerging from an ancient civilization in the context of European colonialism. The modern Iranian public sphere, Dabashi argues, cannot be understood apart from this dynamic interaction.

Persophilia takes into its purview works as varied as Xenophon’s Cyropaedia and Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Handel’s Xerxes and Puccini’s Turandot, and Gauguin and Matisse’s fascination with Persian art. The result is a provocative reading of world history that dismantles normative historiography and alters our understanding of postcolonial nations.

Our foremost theorist of myth, fairytales, and folktales explores the magical realm of the imagination where carpets fly, objects speak, dreams reveal hidden truths, and genies grant prophetic wishes. Stranger Magic examines the wondrous tales of the Arabian Nights, their profound impact on the West, and the progressive exoticization of magic since the eighteenth century, when the first European translations appeared.

The Nights seized European readers' imaginations during the siècle des Lumières, inspiring imitations, spoofs, turqueries, extravaganzas, pantomimes, and mauresque tastes in dress and furniture. Writers from Voltaire to Goethe to Borges, filmmakers from Raoul Walsh on, and countless authors of children's books have adapted its stories. What gives these tales their enduring power to bring pleasure to readers and audiences? Their appeal, Marina Warner suggests, lies in how the stories' magic stimulates the creative activity of the imagination. Their popularity during the Enlightenment was no accident: dreams, projections, and fantasies are essential to making the leap beyond the frontiers of accepted knowledge into new scientific and literary spheres. The magical tradition, so long disavowed by Western rationality, underlies modernity's most characteristic developments, including the charmed states of brand-name luxury goods, paper money, and psychoanalytic dream interpretation.

In Warner's hands, the Nights reveal the underappreciated cultural exchanges between East and West, Islam and Christianity, and cast light on the magical underpinnings of contemporary experience, where mythical principles, as distinct from religious belief, enjoy growing acceptance. These tales meet the need for enchantment, in the safe guise of oriental costume.

The Sublime South: Andalusia, Orientalism, and the Making of Modern Spain is the first systematic study on cultural images of Andalusia as Spain’s “Orient” and the impact they have had on nation-building and modernization since the late nineteenth century. While a wealth of studies have examined how northern Europeans from the Romantic period viewed Spain and Andalusia as Europe’s Orient, little attention has been paid to how contemporary Spanish artists and intellectuals assimilated Romantic legacies to engage in an internal form of orientalism.

José Luis Venegas deftly explores Spain’s shifting engagements with oriental identity and otherness by looking, not just beyond national, ethnic, and racial borders, but at a territory that is institutionally embedded in the nation-state while symbolically placed between inclusion and abjection. The Sublime South shifts the focus and scale of Edward Said’s notion of orientalism by examining how it evolves and manifests transnationally, as the result of European colonialism in Africa and Asia, and intra-nationally, in a European yet orientalized country. Finally, Venegas challenges ethnocentric notions of Iberian cultures and fosters an understanding of the encounters between Western and Muslim cultures beyond opposing, and often mutually negating, essentialisms.

The Sheik. Pépé le Moko. Casablanca. Aladdin. Some of the most popular and frequently discussed titles in movie history are imbued with orientalism, the politically-charged way in which western artists have represented gender, race, and ethnicity in the cultures of North Africa and Asia. This is the first anthology to address and highlight orientalism in film from pre-cinema fascinations with Egyptian culture through the "Whole New World" of Aladdin. Eleven illuminating and well-illustrated essays utilize the insights of interdisciplinary cultural studies, psychoanalysis, feminism, and genre criticism. Other films discussed includeThe Letter, Caesar and Cleopatra, Lawrence of Arabia, Indochine, and several films of France's cinéma colonial.

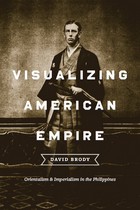

In 1899 an American could open a newspaper and find outrageous images, such as an American soldier being injected with leprosy by Filipino insurgents. These kinds of hyperbolic accounts, David Brody argues in this illuminating book, were just one element of the visual and material culture that played an integral role in debates about empire in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America.

Visualizing American Empire explores the ways visual imagery and design shaped the political and cultural landscape. Drawing on a myriad of sources—including photographs, tattoos, the decorative arts, the popular press, maps, parades, and material from world’s fairs and urban planners—Brody offers a distinctive perspective on American imperialism. Exploring the period leading up to the Spanish-American War, as well as beyond it, Brody argues that the way Americans visualized the Orient greatly influenced the fantasies of colonial domestication that would play out in the Philippines. Throughout, Brody insightfully examines visual culture’s integral role in the machinery that runs the colonial engine. The result is essential reading for anyone interested in the history of the United States, art, design, or empire.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press