Cloth: 978-0-8173-1628-0 | Paper: 978-0-8173-5508-1 | eISBN: 978-0-8173-8076-2

Library of Congress Classification F1619.2.T3K45 2008

Dewey Decimal Classification 972.900497922

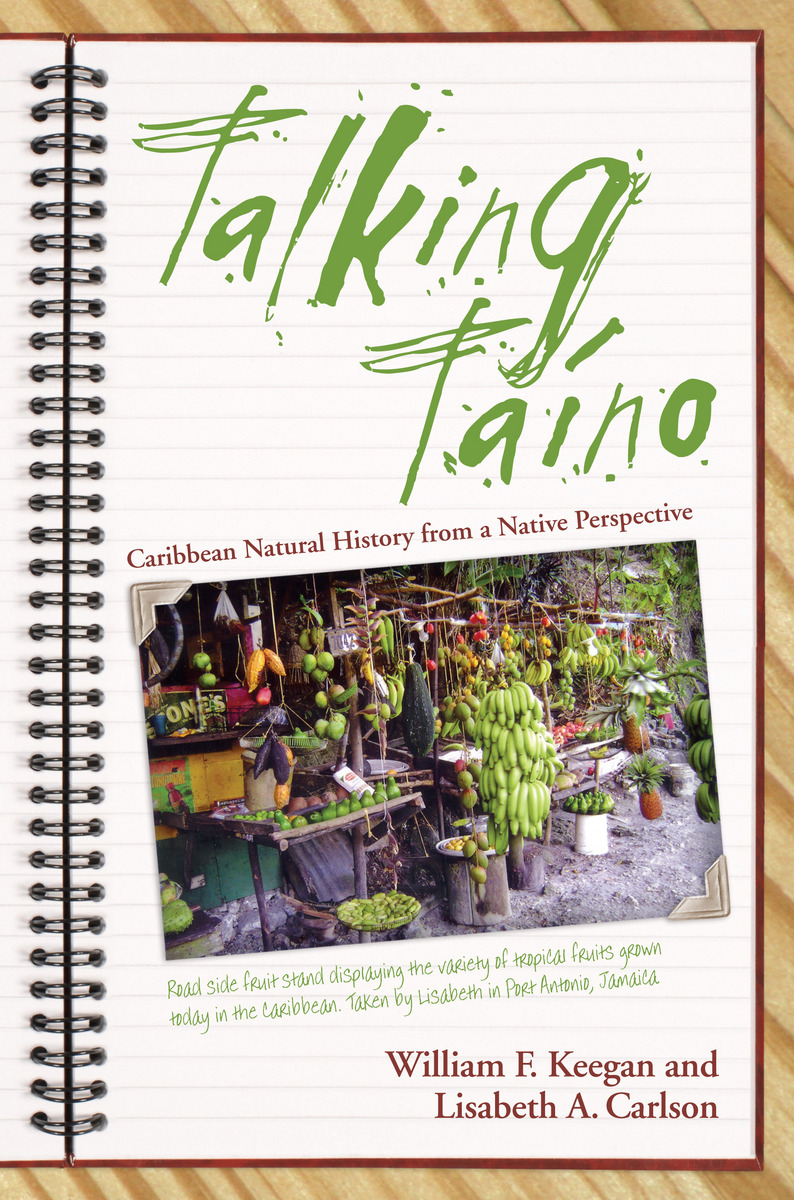

Keegan and Carlson, combined, have spent over 45 years conducting archaeological research in the Caribbean, directing projects in Trinidad, Grenada, St. Lucia, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Cuba, Jamaica, Grand Cayman, the Turks & Caicos Islands, and throughout the Bahamas. Walking hundreds of miles of beaches, working without shade in the Caribbean sun, diving in refreshing and pristine waters, and studying the people and natural environment around them has given them insights into the lifeways of the people who lived in the Caribbean before the arrival of Christopher Columbus. Sadly, harsh treatment extinguished the culture that we today call Taíno or Arawak.

In an effort to repay their debt to the past and the present, the authors have focused on the relationship between the Taínos of the past (revealed through archaeological investigations) and the present natural history of the islands. Bringing the past to life and highlighting commonalities between past and present, they emphasize Taíno words and beliefs about their worldview and culture.

William F. Keegan is Chairman and Curator of Caribbean Anthropology, Department of Natural History, at the Florida Museum of Natural History. He also serves as Associate director for Research and Collections. He holds affiliate appointments as Professor of Anthropology and Curator of Latin American Studies at the University of Florida. He is also affiliate faculty in the College of Natural Resources and the Environment.

Lisabeth A. Carlson is a Senior Archaeologist with Southeastern Archaeological Research, Inc. (SEARCH) in Jonesville, Florida.

Contents

List of Illustrations 000

Preface 000

Acknowledgments 000

Introduction 000

1. The Spanish Translation (2003) 000

2. Starry, Starry Night (2005) 000

3. Sharks and Rays (2003) 000

4. First Documented Shark Attack in the Americas, circa AD 1000 (2003) 000

5. The Age of Reptiles (2003) 000

6. Catch of the Day (2007) 000

7. Birdland (2006) (cowritten by Dr. David Steadman) 000

8. Gone Fishin' (2004) 000

9. In the Beginning, God Created Fish (2004) 000

10. Herbs, Fish, and Other Scum and Vermin (2003) 000

11. The Chip-Chip Gatherers (2007) 000

12. Eats, Shoots, and Leaves (2004) 000

13. Eat Roots and Leave (2004) 000

14. If You Like Pina Coladas . . . (2005) 000

15. Boat Trips (2006) 000

16. Partying, Taino Style (2007) 000

17. Caves (2006) 000

18. Birds of a Feather (2005) 000

19. Cannibals! (2006) 000

20. Obeah and Zombies: The African Connection (2005) 000

21. The Stranger King (2007) 000

22. Anatomy of a Colony: A Taino Outpost in the Turks & Caicos Islands (1997)

000

23. Columbus, Hero or Heel? (1991) 000

24. One Small Step for a Man (1991) 000

25. A World on the Wax 000

Introduction to the Appendices: Words (Between the Lines of Age) 000

Appendix 1: Taino Names for Fishes 000

Appendix 2: Taino Names for Animals 000

Appendix 3: Other Taino Words 000

Bibliography 000

Index 000

Illustrations

1. Feral donkeys on Grand Turk near North Wells 000

2. Map of the insular Caribbean showing culture areas 000

3. Columbus claiming possession of his first landfall in the Bahamas

(Guanahani) 000

4. MC-6 site map showing plazas surrounded by midden concentrations and

structural remains 000

5. Alignments at MC-6 between the east-west stone alignments, the central

stone, and the structural foundations surrounding the plaza as they relate to

the rising and setting of the summer solstice sun and various stars 000

6. Drawing of the constellation Orion with lines added to depict the "one-

legged man" 000

7. Burial number 17, a twenty-nine-year-old male who was fatally attacked by

a tiger shark more than one thousand years ago 000

8. Close-up view of tiger shark tooth marks on lateral and posterior surface

of humeral shaft 000

9. Extreme close-up of the shark tooth damage 000

10. Picnic area at Guantanamo Naval Base reminding people not to feed the

iguanas 000

11. Rock iguana bones from GT-3 on Grand Turk 000

12. The Taino word baracutey described the fish we today call barracuda 000

13. The barracuda is a dangerous predator that has numerous razor-sharp

pointed teeth 000

14. Drilled barracuda tooth pendant from Site AR-39 (Rio Tanama Site 2) in

Puerto Rico 000

15. Bones found in excavations of Indian cave, Middle Caicos, from both

living and extinct species of birds 000

16. Flamingo tongue shell with two rough perforations, possibly used as a

fishing lure or line sinker, from Site Ceiba 11, Puerto Rico 000

17. Perforated clam and oyster shells (possible net or line sinkers), from

Site Ceiba 11, Puerto Rico 000

18. Notched stone net sinkers (potala) from the site of Ile a rat, Haiti

000

19. Shell scrapers made from two species of clams, from Site Ceiba 11, Puerto

Rico 000

20. Bill Keegan removing a conch from its shell in the manner of the Tainos

000

21. Shell bead necklace reconstructed from conch and jewel box shell disk

beads excavated from the Governor's Beach site, Grand Turk 000

22. Manioc roots 000

23. Ceramic griddle fragments from Site AR-39 (Rio Tanama Site 2) in Puerto

Rico 000

24. Map showing the shallow banks north of Hispaniola 000

25. Canoe paddle from the Coralie site, Grand Turk 000

26. Photo of ship etchings in doorframe of Turks & Caicos Loyalist Plantation

000

27. Taino table used for inhaling cohoba carved in the form of a bird, from

Jamaica 000

28. Trumpet made from Atlantic Triton's trumpet shell excavated from the

Governor's Beach site, Grand Turk 000

29. Painted Taino image (pictograph) in cave in Parque del Este, Dominican

Republic 000

30. Petroglyphs recorded in 1912 by Theodoor de Booy near Jacksonville, East

Caicos 000

31. Petroglyphs recorded in 1912 by Theodoor de Booy on Rum Cay, Bahamas

000

32. Owl image on modeled pottery adorno from Jamaica 000

33. Line drawing of a perforated and incised belt ornament made from a human

skull 000

34. Wooden statue of Opiyelguobiran, the dog god who carried spirits to the

world of the dead 000

35. Close-up of porcupine fish 000

36. Pottery effigy vessel in the shape of a porcupine fish from the

Governor's Beach site, Grand Turk 000

37. Archaeological excavations at the Coralie site in 1996, Grand Turk 000

38. Stone-and-conch-shell-lined hearth on which an overturned sea turtle

carapace was used to cook a meal, Coralie site, Grand Turk 000

39. Pigeon sitting on the head of the statue of Columbus in Parque Colon,

Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic 000

40. Sunset behind the Pitons, St. Lucia 000

Plates

1. Saladoid pot stand from Grenada

2. Reconstructed Taino houses (bohio) on San Salvador, Bahamas

3. Cleared area of stone-lined courtyard at the middle of the site of MC-6 on

Middle Caicos

4. Southern stingray over a reef in the Turks & Caicos Islands

5. Worked shark teeth from the site of MC-6 on Middle Caicos

6. Large rock iguana on Guantanamo Naval Base

7. Stoplight parrotfish jawbone

8. Stoplight parrotfish

9. Broken ceramic sherds from the site of Ile a rat, Haiti

10. Land crabs (juey), Delectable Bay, Acklins Islands, Bahamas

11. Chitons and nerites living on rocky intertidal shores in the Turks &

Caicos Islands

12. Whole breadfruits roasting in roadside firepit, Boston Bay, Jamaica

13. Bougainvillea and Casaurina: Grand Turk's imported landscape

14. Handcrafted dinghy

15. Handmade raft from Haiti

Plates follow page 000

Preface

The gray beard (Bill, not Betsy) is telling. Combined, the two of us have

spent forty-five years conducting archaeological research in the Caribbean.

Bill started in 1978, and Betsy in 1992. Over the years we have directed

research projects in Trinidad, Grenada, St. Lucia, Puerto Rico, the Dominican

Republic, Haiti, Cuba, Jamaica, Grand Cayman, the Turks & Caicos Islands, and

throughout the Bahamas. We have also had the good fortune to visit many of

the other islands in the Caribbean.

Our experiences have been remarkable. We've walked hundreds of miles of

Caribbean coastline, dodged drug smugglers, camped on beaches miles from

humanity, seen the night sky in the total absence of other light, scuba dived

in pristine waters, searched for glass fishing floats on beaches that no one

ever visits, and enjoyed the wonders of nature that surrounded us. Most of

all, wherever we went, we were welcomed by the friendly people who today live

in these islands. It is an understatement to say that we were welcomed with

open arms; it is more accurate to say that they adopted us!

The main reason we made these trips was to study the lifeways of the

peoples who lived in the Caribbean before the arrival of Christopher

Columbus. Sadly, harsh treatment and European diseases extinguished their

culture, a culture we today call Taino (also known as Arawak). In an effort

to repay our debt to the past and the present we began writing a series of

short essays called "Talking Taino." The bottom line for each essay was

showing the relationship between the Tainos of the past and the present

natural history of the islands. Our goal has been to bring the past to life

and to highlight commonalities between past and present. We did so by

emphasizing Taino words and beliefs about the natural world.

Most of the essays have a Taino word list and English translation. The

most comprehensive discussion of Caribbean languages was published by Julian

Granberry and Gary Vescelius (2004). It should be noted that Taino was not a

written language, and thus there are a variety of spellings for the same word

(e.g., zemi and cemi, Xaragua and Jaragua). The main issue is finding the

letters that appropriately express particular pronunciations. In this regard,

Granberry and Vescelius do an excellent job of capturing the proper

pronunciation of Taino words. Nevertheless, we have chosen some spellings

included in Spanish publications that we feel better capture the Taino

language.

We encourage anyone who is interested in talking Taino to consult the

phonetic spellings provided in the book by Granberry and Vescelius, because

the Spanish spellings for these words often yield pronunciations that would

be spelled differently in English. For example, gua is pronounced wa; and the

consonant c can have a hard or soft pronunciation (thus, conuco is pronounced

konuko, while cemi is pronounced seme). Speaking the language requires

specific knowledge of translation and pronunciation.

We initially wanted to call this collection "Buffalo Sojourn." The

first meaning was a play on words that we hoped reggae fans would recognize

immediately ("Buffalo Soldier"). A key line from Bob Marley's song is, "If

you know your history, then you will know where you're coming from." Our

intent in writing these essays was to provide a more detailed introduction to

the natural history of the islands.

There was also a more personal connection. We began work on several

archaeological research projects in the Turks & Caicos Islands in 1989, and

were invited to Jamaica by Mr. Tony Clarke in 1998. One of our first

(nonarchaeological) discoveries was that many of the feral donkeys that we

had seen wandering the streets of Grand Turk had been airlifted to Jamaica,

and were now thriving in the lush pastures of Tony's Paradise Park dairy

farm. Tony was looking for an archaeologist to investigate the site on his

property, and heard of us during the process of arranging the transfer of

donkeys. We have worked for donkeys in the past, but this is the first time

one got us a job! Several years later we encountered many new residents.

Fidel Castro presented the prime minister of Jamaica with twelve water

buffalos as a special gift in recognition of their many years of cooperation.

This was a very practical gift, and it shows that heads of state are not

always motivated by pomp and circumstance. But no water buffalo would want to

live on the streets of Kingston, so they were distributed to several farms in

the country, and four of them were sent to Paradise Park. The hope was that

they would eat the water hyacinth that was clogging the Dean's Valley River,

but they actually preferred pasture grass. We always thought that grass was

grass, but these farms actually plant special pasture grasses for their dairy

cows. The donkeys and water buffalos are thrilled! We spent five field

seasons at Paradise Park working near our donkey friends from Grand Turk and

the water buffalos from Cuba.

Very different worlds were thrust together into a common history five

hundred years ago. We hope you will appreciate with us the wonders of the

Caribbean world, the peoples who lived there in the past, and those who live

there today. They are, whether you know it or not, an integral part of who

you are.

Acknowledgments

There are far too many people to thank for their assistance on our

various projects. First and foremost we met a strong and dedicated ally.

Kathy Borsuk, managing editor of the International Magazine of the Turks &

Caicos Islands, called Times of the Islands, embraced our concept. Most of

the chapters in this book originally were published there. Kathy has created

a phenomenal publication that reaches well beyond the Turks & Caicos Islands.

We encourage everyone to subscribe, or at the very least, visit the

magazine's web page: <www.timespub.tc.>

Most of these essays benefited greatly from discussions with our

colleagues at the Florida Museum of Natural History. In particular, Dr. David

Steadman (curator of Ornithology) coauthored one of the papers ("Birdland").

We appreciate his permission and willingness to include that essay in this

collection and thank him for his permission to reproduce several of his

photographs. We also appreciate the support of Dr. Douglas S. Jones, director

of the Florida Museum of Natural History, for his support and permission to

publish the shark attack essay that originally was published on the museum's

web pages. Finally, VISTA magazine solicited articles on Columbus for their

Sunday newspaper supplement. We appreciate their permission to include two of

those here. We thank Dr. Peter Siegel for providing photos from the

excavations at Maisabel, Puerto Rico, and we greatly appreciate the beautiful

fish photographs provided by Barbara Shively and the artifact photographs

provided by Corbett McP. Torrence.

We are especially fortunate that The University of Alabama Press found

our work of sufficient interest to collect these writings in a book. It has

been a pleasure to work with the staff at the press.

Talking Taino

Introduction

They are known today as Lucayan Tainos: an anglicized version of the

Spanish "Lucayos," which derives from the Arawakan words Lukkunu Kairi

("island men"). The Lucayans share a common ancestry with the Taino societies

of Puerto Rico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Jamaica (the Greater

Antilles), who they separated from around AD 600 when they began to colonize

the Turks & Caicos and the Bahamas (hereafter called the Lucayan Islands). By

1492, they had settled all of the larger Lucayan Islands. In addition, they

continued to exchange goods with other Tainos living in the Greater

Antilles.

To date, most of what has been written about the Tainos has drawn upon

the written record left by the Spanish. However, because the chronicles were

written to serve political objectives, be they for or against the native

peoples, and because the chroniclers themselves were limited in their

abilities to understand a nonwestern culture, these documents are rife with

errors and misinformation. The uncritical use of the historical record has

hampered efforts to understand native West Indian societies. For although we

continue to speak of Tainos as a single unified group, there were regional

differences in language and culture, if not also in race. One needs look only

to the Soviet Union or the former Yugoslavia to be reminded of the fragility

of national identities. This introduction draws on the last two decades of

anthropological scholarship to present a brief chronicle of the development

and extinction of Lucayan Taino culture.

<b>Origins</b>

The origins of the Lucayan Tainos are traced to the banks of the Orinoco

River in Venezuela. As early as 2100 BC villages of horticulturalists who

used pottery vessels to cook their food had been established along the Middle

Orinoco. During the ensuing two millennia their population increased in

numbers, and they expanded down river and outward along the Orinoco's

tributaries to the coasts of Venezuela, the Guianas, and Trinidad. Their

movements are easily traced because the pottery they manufactured is so

distinctive. Called Saladoid after the archaeological site of Saladero,

Venezuela, their vessels were decorated with white-on-red painted, modeled

and incised, and crosshatched decorations (see plate 1).

Saladoid peoples expanded through the Antilles at a rapid pace. Because

their earliest settlements, which date before 400 BC, are in the Leeward

Islands, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico, the inescapable conclusion is

that most of the Lesser Antilles were leapfrogged in a direct jump from

Venezuela/Trinidad to Puerto Rico and its neighbors. Moreover, the

conditions, which stimulated the initial migration into the Antilles,

continued to fuel dispersal from South America bringing a variety of related

ethnic groups into the Antilles over the next millennium.

Saladoid peoples lived in small villages and practiced swidden

agriculture in which a variety of different crops were cultivated in small

gardens, a practice very similar to present-day "casual cultivation." Due to

the limited fertility of the soil gardens, they were cultivated for only a

few years before new gardens had to be cleared. Frequent movement of village

sites is evident from the absence of deeply stratified sites. A number of the

early sites are located inland on watercourses adjacent to prime agricultural

land, but most Saladoid sites are in coastal settings. In both settings,

horticulture was the primary source of food. At the inland sites land crab

remains are the main component, while at coastal villages the shells of

marine mollusks and bones of fishes were the most common food remains in the

trash middens.

For some reason the Saladoid advance stalled after they had colonized

eastern Hispaniola. Irving Rouse (1992) has suggested that a large and well-

established population of hunter-gatherers barred their forward progress, and

that the Saladoid population needed time to grow and refine their adaptation

to island life before the frontier was breached. Some of the resident

foragers may have been assimilated before further expansion took place.

The next phase of cultural development is announced by a marked change

in material culture. Elaborate pottery decorations disappear, especially in

frontier locations where most of the pottery was undecorated except for

occational red slip or simple modeling. These simplified designs have been

classified as the Ostionoid series, named for the archaeological site of

Ostiones in western Puerto Rico. By AD 600 the "Ostionoid peoples" had

resumed the advance of their Saladoid ancestors and had begun to expand along

both coasts of Hispaniola. Expansion along the southern coast led to the

colonization of Jamaica, while movement through the northern valleys led to

the colonization of eastern Cuba, the Bahamas, and the Turks & Caicos.

Given the modern barren landscape of the Lucayan Islands it is often

asked why anyone would leave the fertile valleys of the Greater Antilles to

settle this island chain. The answer is that although the Lucayan Islands are

today covered by low scrub vegetation and there is a noticeable lack of fresh

water, these conditions did not prevail five hundred years ago. In fact, the

Lucayan Islands would have been quite attractive to small groups of

horticulturalists who farmed the loamy soils and relied on the sea for fish

and transport.

<b>Diet</b>

Spanish records indicate that the Lucayan Tainos cultivated as many as

fifty different plants, including varieties of sweet and bitter manioc, sweet

potatoes, cocoyams, beans, gourds, chili peppers, corn, cotton, tobacco,

bixa, genip, groundnuts, guava, and papaya. The carbonized remains of corn,

chili peppers, palm fruits, unidentified tubers (probably manioc and sweet

potato), and gourds are among the plant remains identified in West Indian

sites. At least half of the Lucayan Taino diet came from plant foods. Manioc

(cassava) was the staple, followed by sweet potato. Corn was cultivated but

apparently was of secondary importance.

Manioc tubers require special processing because they contain poisonous

hydrocyanic acid. Sweet manioc has such small quantities of the poison it can

be prepared like sweet potato--peeled and boiled. Bitter manioc, however,

requires a more elaborate procedure which involves peeling, grinding or

mashing, and squeezing the mash in a basket tube to remove the poisonous

juices (see chapter 13). After the juice is removed the paste is dried and

sieved for use as flour. Water is added to the flour to make the pancake-like

cassava bread, which is cooked on a flat clay griddle. Fragments of these

griddles and large ceramic bowls, both of which were made from red loam and

crushed, burned conch shell, are common in Lucayan Island archaeological

sites.

The poisonous manioc juice is not discarded. It is boiled to release

the poison and then used as the liquid base for "pepper pot" stew. Adding

chili peppers, other vegetables, meat and fish to the simmering manioc juice

makes pepper pot. This slow simmering stew allowed food that would otherwise

spoil to be preserved and available for meals throughout the day. Today in

South America, pepper pot is still eaten with cassava bread.

The other half of the diet came from creatures of the land and the sea.

The few land animals that were available (iguana, crabs, and a cat-size

rodent called hutia) were highly prized, but were only available in limited

quantities. The major source of animal protein came from the coastal marine

environment. Marine turtles and monk seals were available seasonally, but the

main foods were the fishes and mollusks who feed in the grass flat/patch reef

habitats between the barrier coral reef and the beach: parrotfish, grouper,

snapper, bonefish, queen conch, urchins, nerites, chitons, and clams. Fish

were captured with nets, basket traps, spears, bow and arrow, and weirs. The

latter involved building check-dams across the mouths of tidal creeks, which

allowed fishes to enter at high tide but prevented their escape when the tide

changed. Meat and fish were grilled with leftovers added to the pepper pot.

When you consider the number of ways Lucayan Tainos could satisfy their

hunger, the islands are noteworthy for the abundance of options. It is

difficult to imagine that anyone ever went hungry, a conclusion confirmed by

the preliminary examination of human skeletal remains, which indicate that

the Lucayan Islanders enjoyed remarkably good health and nutrition. They

certainly did not suffer from the nutritional and diet-related disorders that

plagued other horticulturalists in the West Indies and elsewhere.

<b>Society and Village Life</b>

The Tainos lived in large multifamily houses. In Hispaniola there were

two kinds of houses: the rectangular caney and the round-to-oval bohio, which

had a high-pitched, conical thatched roof (see plate 2). Although a probable

exaggeration, the early sixteenth-century Spanish chronicler Bartolome de las

Casas reported that some houses were occupied by 40 to 60 heads of household

(roughly 250 men, women, and children). Households were formed around a group

of related females. Grandmother, mother, sisters, and daughters lived

together and cooperated in farming, childrearing, food preparation, and craft

production. Men, by virtue of their absence from communities during periods

of long-distance trade and/or warfare, were peripheral to the household. The

importance of females as the foundation of society was expressed by tracing

descent through the female line to a mythical female ancestress. This

"matrilineal" social organization is common throughout the world.

The household's belongings were stored on the floors and in the rafters

of the houses. Cotton hammocks for sleeping were strung between the central

supports and eaves. Excavations of a house floor at a site in the Turks &

Caicos Islands revealed ash deposits, which may have come from small, smoky

fires used to control insect pests and to warm the house at night. Cooking

was probably done in sheds outside the main house.

Most villages in the Lucayan Islands were composed of houses aligned

atop a sand dune with the ocean in front and a marshy area behind. Quite

likely, these marshy areas provided ready access to fresh water before the

islands were deforested. In addition, many sites are located just offshore on

small cays.

Lucayan Taino sites often occur in pairs, which reflects either

cooperation between socially allied communities or sequential settlements in

the same location. The former possibility is more likely because it is the

men who most often were the leaders, even in matrilineages, and especially

with regard to external relations. In a matrilineal society, your mother's

brother, and not your father, is the most important male in your life because

he heads your family's lineage. However, if men are needed by their

matrilineage, yet are expected to live in their wife's village, then social

relations will be unstable. These competing demands can be balanced by

establishing villages in close proximity, thus reducing the distances that

men must travel to participate in their lineage affairs.

In the Greater Antilles a slightly different type of community plan

predominates. Here the houses are arranged around central plazas. The plazas

were used for public displays, ritual dances, recording astronomical events,

and for the Taino version of the ball game. The chief's house, typically

located at one end of the plaza, stored the village idols and spirit

representations called cemis.

<b>Religion</b>

The Taino pantheon of cemis was divided by the dichotomies of gender and

cultural/noncultural. There were principal male and female spirits of

fruitfulness: Yocahu, the giver of manioc, and Attabeira, the mother goddess.

They both were attended by twin spirits. Maquetaurie Guayaba, Lord of the

Dead, and Guabancex, Mistress of the Hurricane, ruled the anticultural world.

They too were attended by sets of twins. Cemis played an active role in the

affairs of humans, and they served to distinguish between that which was

human, cultural, and pleasing and that which was nonhuman, anticultural, and

foul. But as exemplified by the twins, the Tainos recognized that the spirits

of the world could simultaneously have positive and negative characteristics.

For example, rains are good when they arrive at the right time and in the

right quantity, but can also devastate agricultural lands when the timing is

wrong or too much rain falls. The Taino viewed their world in a delicate

balance, and they attended to their spirits in order to maintain this

balance.

<b>Political Organization</b>

By the time Europeans arrived, Taino society had two main divisions. The

rulers of the community were of a noble class (called niTainos), which

included chiefs, shamans, and other elites who held positions of authority.

Chiefs (called caciques) ruled at several levels, from the paramount caciques

that ruled large regions, to district leaders who were allied to a paramount,

to headmen and clanlords who ruled at the village level. With noble birth

being the main prerequisite of this rank, it should be noted that women could

also be chiefs. Between caciques of all levels, alliances were formed through

marriages.

Supporting the rulers were large numbers of commoners. Blood and

marriage (kinship) were the threads that bound commoners to caciques. There

was also a level below the commoner class, which the Spanish described as a

class of servants called naborias. Naborias were once thought to be slaves,

but a careful reading of the early Spanish chronicles indicates that they

served through a sense of obligation and were not chattel.

Caciques organized villages into regional polities who competed with

one another for a variety of resources. There is increasing evidence that,

contrary to the "peaceful Arawak" stereotype, the Taino chiefdoms made war on

one another prior to the arrival of the Spanish.

Caciques also organized long-distance trade. Travel between islands was

accomplished in canoes dug out of a single log. The largest of which could

carry approximately ninety passengers. Traders sought both domestic trade

items (salt, dried fish, and conch) and exotic materials from other chiefdoms

and from neighboring islands. The red jewel box shell (Chama sarda) disk

beads that were manufactured throughout the Lucayan Islands are an example of

an exotic good. These beads were woven into belts that served to record

alliances between chiefdoms. These and other exotic materials served to

reinforce the authority of the caciques to whom access to these goods was

restricted. By one account, Taino caciques held authority of life or death

over their subjects.

<b>Warfare</b>

When Columbus set foot on the island he called San Salvador, young men

carrying spears who were there to defend their village met him. Other

encounters between the Spanish and the Tainos also point to the importance of

warfare in Taino society. For instance, when Columbus embarked on the

conquest of central Hispaniola in 1494 he was challenged by an army of up to

fifteen thousand warriors (although this may have been an exaggeration).

Moreover, shortly after the Spanish arrested Caonabo, the cacique of the

central Hispaniola region of Maguana, Bartholomew Columbus was passing along

the Neiba River, which formed the boundary between the regions of Xaragua and

Maguana. Here he encountered an army from Xaragua that was probably in the

area to co-opt villages that had previously been allied with the deposed

Chief Caonabo. Taino social organization also points to the presence of an

organized and well-armed militia.

<b>Genocide</b>

Within a generation of the arrival of the Spanish, the native peoples of

the Lucayan Islands were extinct. In 1513, Juan Ponce de Leon sailed through

the Lucayan Islands on his way to Florida. He reported that he encountered

only one inhabitant, an old native man still living in the Turks & Caicos

Islands. Other expeditions followed, including two in 1520, which failed to

encounter any native peoples in these islands.

The fate of the Lucayan Tainos can be traced to the mines on Hispaniola

and to the pearl beds of Cubagua Island off the coast of Venezuela. By 1509,

the Spanish governor of Santo Domingo had convinced King Ferdinand that there

was a critical shortage of labor on Hispaniola. In response the king ordered

that all peoples from the neighboring islands be relocated to Hispaniola. A

slaving consortium was soon formed in Concepcion de la Vega, although

documents in the archives in Seville suggest that the practice of enslaving

Lucayans had begun much earlier. The contact period chronicler Peter Martyr

reported that forty thousand Lucayans were brought to Hispaniola. The total

population of the islands was probably twice that number when children, old

people, and others who died are included. A total population of forty to

eighty thousand Lucayans is consistent with archaeological deposits in these

islands.

When Columbus landed at Guanahani in 1492 he was met by people whose

simple dress and material technology belied their social and political

complexity. Theirs was a vibrant culture in the process of filling up the

northern and western Lucayan Islands at the same time they were competing

among themselves for political and economic control of the central islands.

Moreover, had the Spanish never arrived, the Lucayan Tainos might soon have

been subject to demands from the Classic Tainos on Hispaniola who were

already establishing bases or outposts in the Turks & Caicos and Great Inagua

by the middle of the thirteenth century. Instead, the Lucayan Tainos are

remembered as the first native peoples to challenge Columbus and the first to

be extinguished.

See other books on: First contact with Europeans | Keegan, William F. | Natural Resources | Taino Indians | West Indies

See other titles from University of Alabama Press