27 start with D start with D

“On a bend, I will see it, a piece of ground off to the side. I will know the feel of this place: the leaves stir slowly on the trees, dry air smells like dust, birds dart and the trails are made by beasts living free.”

When award-winning author Charles Bowden died in 2014, he left behind a trove of unpublished manuscripts. Dakotah marks the landmark publication of the first of these texts, and the fourth installment in his acclaimed “Unnatural History of America.” Bowden uses America’s Great Plains as a lens—sometimes sullied, sometimes shattered, but always sharp—for observing pivotal moments in the lives of anguished figures, including himself.

In scenes that are by turns wrenching and poetic, Bowden describes the Sioux’s forced migrations and rebellions alongside his own ancestors’ migrations from Europe to Midwestern acres beset by unforgiving winters. He meditates on the lives of his resourceful mother and his philosophical father, who rambled between farm communities and city life. Interspersed with these images are clear-eyed, textbook-defying anecdotes about Lewis and Clark, Daniel Boone, and, with equal verve, twentieth-century entertainers “Pee Wee” Russell, Peggy Lee, and other musicians. The result is a kaleidoscopic journey that penetrates the senses and redefines the notion of heartland. Dakotah is a powerful ode to loss from one of our most fiercely independent writers.

A significant and innovative contribution to Austin studies. How did an Illinois Methodist homesteader in the West come to create one of the most significant cosmological syntheses in American literature? In this study, Hoyer draws on his own knowledge of biblical religion and Native American cultures to explore Austin's creation of the "mythology of the American continent" she so valued. Austin lived in and wrote about "the land of little rain," semiarid and arid parts of California and Nevada that were home to the Northern Paiute, Shoshone, Interior Chumash, and Yokut peoples. Hoyer makes new and provocative connections between Austin and spiritual figures like Wovoka, the prophet of the Ghost Dance religion, and writers like Zitkala-sa and Mourning Dove, and he provides a particularly fine reading of Cogowea.

A fur trader in the Michigan Territory and confidant of both the U.S. government and local Indian tribes, Jacob Smith could have stepped out of a James Fenimore Cooper novel. Controversial, mysterious, and bold during his lifetime, in death Smith has not, until now, received the attention he deserves as a pivotal figure in Michigan’s American period and the War of 1812. This is the exciting and unlikely story of a man at the frontier’s edge, whose missions during both war and peace laid the groundwork for Michigan to accommodate settlers and farmers moving west. The book investigates Smith’s many pursuits, including his role as an advisor to the Indians, from whom the federal government would gradually gain millions of acres of land, due in large part to Smith’s work as an agent of influence. Crawford paints a colorful portrait of a complicated man during a dynamic period of change in Michigan’s history.

Dark Thirty takes us on a loosely autobiographical trip through Cherokee country, the backwoods towns and the big cities, giving us clear-eyed portraits of Native people surviving contemporary America. In Frazier’s world, there is no romanticizing of Native American life. Here cops knock on the door of a low-rent apartment after a neighbor has been stabbed. Here a poem’s narrator recalls firing a .38 pistol—“barrel glowing like oil in a gutter-puddle”—for the first time. Here a young man catches a Greyhound bus to Flagstaff after his ex-girlfriend tells him he has fathered a child. Yet even in the midst of violence and despair there is time for the beauty of the world to shine through: “The Cutlass rattling out / the last fumes of gas, engine stops, / the night dimly lit by the moon / hung over the treetops; / owls calling each other from / hilltop to valley bend.”

Like viewing photographs that repel us even as they draw us in, we are pulled into these poems. We’re compelled to turn the page and read the next poem. And the next. And each poem rewards us with a world freshly seen and remade for us of sound and image and voice.

Many people living far away from Indian reservations express sympathy for the poverty and misery experienced by Native Americans, yet, Thomas Biolsi argues, the problems faced by Native Americans are the results of white privilege.

In Deadliest Enemies, Biolsi connects the origins of racial tension between Indians and non-Indians on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota to federal laws, showing how the courts have created opposing political interests along race lines. Biolsi demonstrates that the court’s definitions of legal rights—both constitutional and treaty rights—make solutions to racial tensions intractable.

This powerful work sheds much-needed light on racial conflicts in South Dakota and in the rest of the United States, and holds white people accountable for the benefits of their racial privilege that come at the expense of Native Americans.

Thomas Biolsi is professor of Native American studies at the University of California at Berkeley.

Deadly Landscapes presents a series of cases that advance the rigorous examination of war in the archaeological record. The studies encompass examples from the Hohokam, Sinagua, Mogollon, and Anasazi regions, plus a pan-regional study of iconography covering the Colorado Plateau and the Rio Grande Valley. All of the cases focus on the narrow time frame from AD 1200 to the early-1400s, during which evidence for warfare is most pervasive.

Contributors to this volume present varying definitions of warfare and use differing types of data to test for the presence of warfare. These detailed case studies give clear demonstration of a pattern of significant warfare in the late prehistoric period that will alter our understanding of ancient Southwestern cultures.

The contributors explore how the inclusion of indigenous histories, and collaboration with contemporary communities and scholars across the subfields of anthropology, can reframe archaeologies of colonialism. The cross-cultural case studies employ a broad range of methodological strategies—archaeology, ethnohistory, archival research, oral histories, and descendant perspectives—to better appreciate processes of colonialism. The authors argue that these more complicated histories of colonialism contribute not only to understandings of past contexts but also to contemporary social justice projects.

In each chapter, authors move beyond an academic artifice of “prehistoric” and “colonial” and instead focus on longer sequences of indigenous histories to better understand colonial contexts. Throughout, each author explores and clarifies the complexities of indigenous daily practices that shape, and are shaped by, long-term indigenous and local histories by employing an array of theoretical tools, including theories of practice, agency, materiality, and temporality.

Included are larger integrative chapters by Kent Lightfoot and Patricia Rubertone, foremost North American colonialism scholars who argue that an expanded global perspective is essential to understanding processes of indigenous-colonial interactions and transitions.

Constructions of America’s ancient past—or the invention of American “prehistory”—occur in national and international political frameworks, which are characterized by struggles over racial and ethnic identities, access to resources and environmental stewardship, the commodification of culture for touristic purposes, and the exploitation of Indigenous knowledges and histories by industries ranging from education to film and fashion. The past’s ongoing appeal reveals the relevance of these narratives to current-day concerns about individual and collective identities and pursuits of sovereignty and self-determination, as well as to questions of the origin—and destiny—of humanity. Decolonizing “Prehistory” critically examines and challenges the paradoxical role that modern scholarship plays in adding legitimacy to, but also delegitimizing, contemporary colonialist practices.

Contributors: Rick Budhwa, Keith Thor Carlson, Kirsten Matoy Carlson, Jessica Christie, Philip J. Deloria, Melissa Gniadek, Annette Kolodny, Gesa Mackenthun, Christen Mucher, Naxaxalhts’i (aka Sonny McHalsie), Jeff Oliver, Mathieu Picas, Daniel Lord Smail, Coll Thrush

Ten scholars whose specialties range from ethnohistory to remote sensing and lithic analysis to bioarchaeology chronicle changes in the way prehistory in the Southeast has been studied since the 19th century. Each brings to the task the particular perspective of his or her own subdiscipline in this multifaceted overview of the history of archaeology in a region that has had an important but variable role in the overall development of North American archaeology.

Some of the specialties discussed in this book were traditionally relegated to appendixes or ignored completely in site reports more than 20 years old. Today, most are integral parts of such reports, but this integration has been hard won. Other specialties have been and will continue to be of central concern to archaeologists. Each chapter details the way changes in method can be related to changes in theory by reviewing major landmarks in the literature. As a consequence, the reader can compare the development of each subdiscipline.

As the first book of this kind to deal specifically with the region, it be will valuable to archaeologists everywhere. The general reader will find the book of interest because the development of southeastern archaeology reflects trends in the development of social science as a whole.

Contributors include:

Jay K. Johnson, David S. Brose, Jon L. Gibson, Maria O. Smith, Patricia K. Galloway, Elizabeth J. Reitz, Kristen J. Gremillion, Ronald L. Bishop, Veletta Canouts, and W. Fredrick Limp

Arturo J. Aldama begins by presenting a genealogy of the term “savage,” looking in particular at the work of American ethnologist Lewis Henry Morgan and a sixteenth-century debate between Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda and Bartolomé de las Casas. Aldama then turns to more contemporary narratives, examining ethnography, fiction, autobiography, and film to illuminate the historical ideologies and ethnic perspectives that contributed to identity formation over the centuries. These works include anthropologist Manuel Gamio’s The Mexican Immigrant: His Life Story, Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera, and Miguel Arteta’s film Star Maps. By using these varied genres to investigate the complex politics of racialized, subaltern, feminist, and diasporic identities, Aldama reveals the unique epistemic logic of hybrid and mestiza/o cultural productions.

The transcultural perspective of Disrupting Savagism will interest scholars of feminist postcolonial processes in the United States, as well as students of Latin American, Native American, and literary studies.

Divided Peoples addresses the impact border policies have on traditional lands and the peoples who live there—whether environmental degradation, border patrol harassment, or the disruption of traditional ceremonies. Anthropologist Christina Leza shows how such policies affect the traditional cultural survival of Indigenous peoples along the border. The author examines local interpretations and uses of international rights tools by Native activists, counterdiscourse on the U.S.-Mexico border, and challenges faced by Indigenous border activists when communicating their issues to a broader public.

Through ethnographic research with grassroots Indigenous activists in the region, the author reveals several layers of division—the division of Indigenous peoples by the physical U.S.-Mexico border, the divisions that exist between Indigenous perspectives and mainstream U.S. perspectives regarding the border, and the traditionalist/nontraditionalist split among Indigenous nations within the United States. Divided Peoples asks us to consider the possibilities for challenging settler colonialism both in sociopolitical movements and in scholarship about Indigenous peoples and lands.

When Hopi/White Mountain Apache anthropologist Tony M. Smokerise is found murdered in his office at Central Highlands University, the task of solving the crime falls to jaded Choctaw detective Monique Blue Hawk and her partner Charles T. Clarke. A seemingly tolerant and amicable office of higher education, the university, Monique soon learns, harbors parties determined to destroy the careers of Tony and his best friend, the volatile Oglala anthropologist Roxanne Badger. In the course of her investigation, Monique discovers that the scholars who control Tony’s department are also overseeing the excavation of a centuries-old tribal burial site that was uncovered during the construction of a freeway. Tony’s role in the project, she realizes, might be the key to identifying his murderer. This virtuosic mystery novel explores, in engrossing detail, the complex motives for a killing within the sometimes furtive and hermetic setting of academia.

In the first half of the book, “Tribal History,” Gould ingeniously repurposes the sonnet form to preserve the stories of her mother and aunt, who grew up when “muleback was the customary mode / of transport” and the “spirit world was present”—stories of “old ways” and places claimed in memory but lost in time. Elsewhere, she remembers her mother’s “ferocious, upright anger” and her unexpected tenderness (“Like a miracle, I was still her child”), culminating in the profound expression of loss that is the poem “Our Mother’s Death.”

In the second half of the book, “It Was Raining,” Gould tells of the years of lonely self-making and “unfulfilled dreams” as she comes to terms with what she has been told are her “crazy longings” as a lesbian: “It’s been hammered into me / that I’ll be spurned / by a ‘real woman,’ / the only kind I like.” The writing here commemorates old loves and relationships in language that mingles hope and despair, doubt and devotion, veering at times into dreamlike moments of consciousness. One poem and vignette at a time, Doubters and Dreamers explores what it means to be a mixed-blood Native American who grew up urban, lesbian, and middle class in the West.

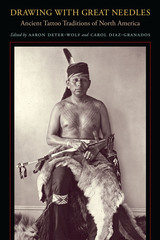

For thousands of years, Native Americans throughout the Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains used the physical act and visual language of tattooing to construct and reinforce the identity of individuals and their place within society and the cosmos. The act of tattooing served as a rite of passage and supplication, while the composition and use of ancestral tattoo bundles was intimately related to group identity. The resulting symbols and imagery inscribed on the body held important social, civil, military, and ritual connotations within Native American society. Yet despite the cultural importance that tattooing held for prehistoric and early historic Native Americans, modern scholars have only recently begun to consider the implications of ancient Native American tattooing and assign tattooed symbols the same significance as imagery inscribed on pottery, shell, copper, and stone.

Drawing with Great Needles is the first book-length scholarly examination into the antiquity, meaning, and significance of Native American tattooing in the Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains. The contributors use a variety of approaches, including ethnohistorical and ethnographic accounts, ancient art, evidence of tattooing in the archaeological record, historic portraiture, tattoo tools and toolkits, gender roles, and the meanings that specific tattoos held for Dhegiha Sioux and other Native speakers, to examine Native American tattoo traditions. Their findings add an important new dimension to our understanding of ancient and early historic Native American society in the Eastern Woodlands and Great Plains.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press