141 start with N start with N

Focusing primarily on a group of Dominican nuns in Strasbourg, Germany, Amy Leonard's Nails in the Wall outlines the century-long battle between these nuns and the Protestant city council. With savvy strategies that employed charm, wealth, and political and social connections, the nuns were able to sustain their Catholic practices. Leonard's in-depth archival research uncovers letters about and records of the nuns' struggle to maintain their religious beliefs and way of life in the face of Protestant reforms. She tells the story of how they worked privately to keep Catholicism alive-continuing to pray in Latin, smuggling in priests to celebrate Mass, and secretly professing scores of novices to ensure the continued survival of their convents. This fascinating and heartening study shows that, far from passively allowing the Protestants to dismantle their belief system, the women of the Strasbourg convents were active participants in the battle over their vocation and independence.

Viennese modernism is often described in terms of a fin-de-siècle fascination with the psyche. But this stereotype of the movement as essentially cerebral overlooks a rich cultural history of the body. The Naked Truth, an interdisciplinary tour de force, addresses this lacuna, fundamentally recasting the visual, literary, and performative cultures of Viennese modernism through an innovative focus on the corporeal.

Alys X. George explores the modernist focus on the flesh by turning our attention to the second Vienna medical school, which revolutionized the field of anatomy in the 1800s. As she traces the results of this materialist influence across a broad range of cultural forms—exhibitions, literature, portraiture, dance, film, and more—George brings into dialogue a diverse group of historical protagonists, from canonical figures such as Egon Schiele, Arthur Schnitzler, Joseph Roth, and Hugo von Hofmannsthal to long-overlooked ones, including author and doctor Marie Pappenheim, journalist Else Feldmann, and dancers Grete Wiesenthal, Gertrud Bodenwieser, and Hilde Holger. She deftly blends analyses of popular and “high” culture, laying to rest the notion that Viennese modernism was an exclusively male movement. The Naked Truth uncovers the complex interplay of the physical and the aesthetic that shaped modernism and offers a striking new interpretation of this fascinating moment in the history of the West.

Winner of the 2021 Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay–NIF Book Prize

The definitive biography of Dadabhai Naoroji, the nineteenth-century activist who founded the Indian National Congress, was the first British MP of Indian origin, and inspired Gandhi and Nehru.

Mahatma Gandhi called Dadabhai Naoroji the “father of the nation,” a title that today is reserved for Gandhi himself. Dinyar Patel examines the extraordinary life of this foundational figure in India’s modern political history, a devastating critic of British colonialism who served in Parliament as the first-ever Indian MP, forged ties with anti-imperialists around the world, and established self-rule or swaraj as India’s objective.

Naoroji’s political career evolved in three distinct phases. He began as the activist who formulated the “drain of wealth” theory, which held the British Raj responsible for India’s crippling poverty and devastating famines. His ideas upended conventional wisdom holding that colonialism was beneficial for Indian subjects and put a generation of imperial officials on the defensive. Next, he attempted to influence the British Parliament to institute political reforms. He immersed himself in British politics, forging links with socialists, Irish home rulers, suffragists, and critics of empire. With these allies, Naoroji clinched his landmark election to the House of Commons in 1892, an event noticed by colonial subjects around the world. Finally, in his twilight years he grew disillusioned with parliamentary politics and became more radical. He strengthened his ties with British and European socialists, reached out to American anti-imperialists and Progressives, and fully enunciated his demand for swaraj. Only self-rule, he declared, could remedy the economic ills brought about by British control in India.

Naoroji is the first comprehensive study of the most significant Indian nationalist leader before Gandhi.

Winner of the J. Russell Major Prize, American Historical Association

Best Book on the First Empire by a Foreigner, Napoleon Foundation

“Englund has written a most distinguished book recounting Bonaparte’s life with clarity and ease…This magnificent book tells us much that we did not know and gives us a great deal to think about.”—Douglas Johnson, Los Angeles Times Book Review

“Englund, in his lively biography…seeks less to rehabilitate Napoleon’s reputation and legacy than to provide readers with a fuller view of the man and his actions.”—Paula Friedman, New York Times

“Napoleon: A Political Life is a veritable tour de force: the general reader will enjoy it immensely, and learn a great deal from it. But the book also has much to offer historians of modern France.”—Sudhir Hazareesingh, Times Literary Supplement

“Englund’s incisive forays into political theory don’t diminish the force of his narrative, which impressively conveys the epochal changes confronting both France and Europe…A strikingly argued biography.”—Matthew Price, Washington Post

This sophisticated and masterful biography brings new and remarkable analysis to the study of modern history’s most famous general and statesman. As Englund charts Napoleon’s dramatic rise and fall—from his Corsican boyhood, his French education, his astonishing military victories and no less astonishing acts of reform as First Consul (1799–1804) to his controversial record as Emperor and, finally, to his exile and death—he explores the unprecedented power Napoleon maintains over the popular imagination.

An Australian Book Review Best Book of the Year

One of France’s most famous historians compares two exemplars of political and military leadership to make the unfashionable case that individuals, for better and worse, matter in history.

Historians have taught us that the past is not just a tale of heroes and wars. The anonymous millions matter and are active agents of change. But in democratizing history, we have lost track of the outsized role that individual will and charisma can play in shaping the world, especially in moments of extreme tumult. Patrice Gueniffey provides a compelling reminder in this powerful dual biography of two transformative leaders, Napoleon Bonaparte and Charles de Gaulle.

Both became national figures at times of crisis and war. They were hailed as saviors and were eager to embrace the label. They were also animated by quests for personal and national greatness, by the desire to raise France above itself and lead it on a mission to enlighten the world. Both united an embattled nation, returned it to dignity, and left a permanent political legacy—in Napoleon’s case, a form of administration and a body of civil law; in de Gaulle’s case, new political institutions. Gueniffey compares Napoleon’s and de Gaulle’s journeys to power; their methods; their ideas and writings, notably about war; and their postmortem reputations. He also contrasts their weaknesses: Napoleon’s limitless ambitions and appetite for war and de Gaulle’s capacity for cruelty, manifested most clearly in Algeria.

They were men of genuine talent and achievement, with flaws almost as pronounced as their strengths. As many nations, not least France, struggle to find their soul in a rapidly changing world, Gueniffey shows us what a difference an extraordinary leader can make.

The French Revolution facilitated the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, but after gaining power he knew that his first task was to end it. In this book William Doyle describes how he did so, beginning with the three large issues that had destabilized revolutionary France: war, religion, and monarchy. Doyle shows how, as First Consul of the Republic, Napoleon resolved these issues: first by winning the war, then by forging peace with the Church, and finally by making himself a monarch. Napoleon at Peace ends by discussing Napoleon’s one great failure—his attempt to restore the colonial empire destroyed by war and slave rebellion. By the time this endeavor was abandoned, the fragile peace with Great Britain had broken down, and the Napoleonic wars had begun.

One of the first books on “Gays in the Military” published following the historic repeal of “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” in 2011, Napoleonic Friendship examines the history of male intimacy in the French military, from Napoleon to the First World War. Echoing the historical record of gay soldiers in the United States, Napoleonic Friendship is the first book-length study on the origin of queer soldiers in modern France. Based on extensive archival research in France, the book traces the development of affectionate friendships in the French Army from 1789 to 1916. Following the French Revolution, radical military reforms created conditions for new physical and emotional intimacy between soldiers, establishing a model of fraternal affection during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars that would persist amid the ravages of the Franco-Prussian War and World War I. Through readings of Napoleonic military memoirs (and other non-fiction archival material) and French military fiction (from Hugo and Balzac to Zola and Proust), Martin examines a broad range of emotional and erotic relationships, from combat buddies to soldier lovers. He argues that the French Revolution’s emphasis on military fraternity evolved into an unprecedented sense of camaraderie in the armies of Napoleon. For many soldiers, the hardships of combat led to intimate friendships. For some, the homosociality of military life inspired mutual affection, lifelong commitment, and homoerotic desire.

Beginning in the 1980s, scientists started traveling to northwest Alaska to research the lives of ringed seals, bringing Labrador retrievers who could sniff out seals and their snow cave homes (called lairs) on the sea ice. Decades later, scientists partnered with the Iñupiaq people of

Qikiktaġruk (Kotzebue) to learn more about ringed seals. They relied on a combination of Indigenous Knowledge and scientific techniques to capture and apply tags to understand the movements and behavior of ringed seals.

But the Arctic homes of ringed seals are changing, and the long history of ringed seal science in the Kotzebue Sound proved to be just the beginning of long and cooperative relationships melding science and Indigenous knowledge. During 2018 and 2019, with unprecedented sea ice conditions, Qikiktagrumiut Elders and scientists returned to the ice to measure changes in the habitat available for ringed seal pups in the region.

Nation and Migration provides a way to understand recent migration events in Europe that have attracted the world's attention. The emergence of the nations in the West promised homogenization, but instead the imagined national communities have everywhere become places of heterogeneity, and modern nation states have been haunted by the specter of minorities. This study analyses experiences relating to migration in 23 European countries. It is based on data from the International Social Survey Programme, a global cross-national collaborative exercise, with surveys made in 1995, 2003, and 2013. In the authors' view, a critical test for Europe will be its ability to find adequate responses to the challenges of globalization.

The book provides a detailed overview of how citizens in Europe are coping with a xenophobia fueled by their own sense of insecurity. The authors reconstruct the competing sociological reactions to migration in the forms of integration, assimilation and segregation. Hungary receives special attention: the data show that people living there are far less closed and xenophobic than they might seem through the prism of a media-instigated moral panic.

In A Nation of Politicians, Padhraig Higgins argues that the development of Volunteer-initiated activities—associating, petitioning, subscribing, shopping, and attending celebrations—expanded the scope of political participation. Using a wide range of literary, archival, and visual sources, Higgins examines how ubiquitous forms of communication—sermons, songs and ballads, handbills, toasts, graffiti, theater, rumors, and gossip—encouraged ordinary Irish citizens to engage in the politics of a more inclusive society and consider the broader questions of civil liberties and the British Empire. A Nation of Politicians presents a fascinating tale of the beginnings of Ireland’s richly vocal political tradition at this important intersection of cultural, intellectual, social, and public history.

Offering a nuanced analysis of how publicity was constructed through radio programming, print media, popular song, and film, Currid examines how German citizens developed an emotional investment in the nation and other forms of collectivity that were tied to the sonic experience. Reading in detail popular genres of music—the Schlager (or “hit”), so-called gypsy music, and jazz—he offers a complex view of how they played a part in the creation of German culture.

A National Acoustics contributes to a new understanding of what constitutes the public sphere. In doing so, it illustrates the contradictions between Germany’s social and cultural histories and how the technologies of recording not only were vital to the emergence of a national imaginary but also exposed the fault lines in the contested terrain of mass communication.

Brian Currid is an independent scholar who lives in Berlin.

Delving into narrative histories, prose fiction, and social philosophy, Hill analyzes the rhetoric, narrative form, and intellectual genealogy of late-nineteenth-century texts that contributed to the creation of national history in each of the three countries. He discusses the global political economy of the era, the positions of the three countries in it, and the reasons that arguments about history loomed large in debates on political, economic, and social problems. Examining how the writing of national histories in the three countries addressed political transformations and the place of the nation in the world, Hill illuminates the ideological labor national history performed. Its production not only naturalized the division of the world by systems of states and markets, but also asserted the inevitability of the nationalization of human community; displaced dissent to pre-modern, pre-national pasts; and presented the subject’s acceptance of a national identity as an unavoidable part of the passage from youth to adulthood.

This meticulously researched and elegantly written book is the most authoritative study of the emergence of modern Romanian identity in Transylvania during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Based upon a plethora of contemporary published sources, Mitu approaches national identity from a variety of perspectives - from within the Romanian community itself and their reaction to the image others had of them.

The author sheds new light on the problems of self-evaluation using a method he describes as "functional analysis" to examine a complex set of ideologies and propaganda. This approach helps the reader to understand the intricate web of contemporary Romanian nationalism.

National Identity of Romanians in Transylvania appeals to scholars of modern Romanian history, those focusing on the Habsburg Monarchy and the study of modern nationalism. The book is an important contribution to the expanding debate on nationalism and national identity from an East European perspective.

In this first English translation of Erika Thurner's National Socialism and Gypsies in Austria, Gilya Gerda Schmidt makes available Thurner’s investigation of Camps Salzburg and Lackenbach, the two central areas of Gypsy persecution in Austria. Two factors made Thurner’s research especially difficult: the Roma and Sinti have more an oral tradition than a written one, and scholarship on the plight of the Gypsies is sparse. Through painstaking research, Thurner has been able to piece together fragments from Nazi documents, recollections of victims, accounts of bystanders and other eyewitnesses, and formal records to present her account. The result is a volume that truly enhances our understanding of the Gypsies’ experiences during this period.

The volume also focuses on broader aspects of the Gypsies’ ordeals: the ideological foundations and legal ordinances regarding Gypsies, the discrimination and persecution in Burgenland as a whole, the transports from Austria to Lodz and Chelmo, and the medical experimentation. The book has also been expanded, with a new study of Camp Salzburg, an updated bibliography, and numerous photographs, which were not included in the German edition.

The recent upsurge of anti-Gypsy violence in Austria illustrates both the horror of the treatment of Gypsy tribes and the timeliness of the subject of this volume.

Ranging widely across countries and centuries, National Thought in Europe critically analyzes the growth of nationalism from its beginnings in medieval ethnic prejudice to the romantic era’s belief in a national soul. A fertile pan-European exchange of ideas, often rooted in literature, led to a notion of a nation’s cultural individuality that transformed the map of Europe. By looking deeply at the cultural contexts of nationalism, Joep Leerssen not only helps readers understand the continent’s past, but he also provides a surprising perspective on contemporary European identity politics.

Nationalizing a Borderland enriches understanding of ethnic conflict by examining the factors in the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia between 1914 and 1920 that led to the rise of xenophobic nationalism and to the ethnocide of World War II. From Russian, Polish, Ukrainian, and Austrian archival sources, Prusin argues that while the violence inflicted upon Jews during that period may at first seem irrational and indiscriminate, a closer examination reveals that it was generated by traditional antisemitism and by the security concerns of the Russian and Polish militaries in the front zone. This violence, Prusin contends, served as a means of reshaping the socio-economic and political space of the province by diminishing Jewish cultural and economic influence.

In this compelling study of the treatment of "enemy" minorities in the Russian Empire during the First World War, Eric Lohr uncovers a dramatic story of mass deportations, purges, expropriations, and popular violence.A campaign initially aimed at restricting foreign citizens rapidly spun out of control. It swept up Russian subjects of German, Jewish, and Muslim backgrounds and drove roughly a million civilians from one part of the empire to another, resulting in one of the largest cases of forced migration in history to that time. Because foreigners and diaspora minorities were prominent among entrepreneurial and landowning elites, the campaign against them also became an explosive element in class and national tensions on the eve of the 1917 revolutions.

During the war, the imperial regime dropped its ambivalence about Russian nationalism and embraced unprecedented and radical policies that "nationalized" the economy, the land, and even the population. The core idea of the campaign--that the country needed to free itself from the domination of foreigners, internal enemies, and the exploitative world economic system--later became a central feature of the Soviet revolutionary model.

Based on extensive archival research, much in newly available sources, Nationalizing the Russian Empire is an important contribution to the study of empire and nationalism, the Russian Revolution, and ethnic cleansing.

The province of Galicia was the easternmost land of the old Habsburg Empire. Throughout the nineteenth century it was noted for political conflicts and the cultural vibrancy of its three major national groups: Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews.

This volume brings together for the first time eleven essays on various aspects of the last seventy-five years of Austrian Galicia's existence. Included are general surveys on Galicia within the imperial Habsburg system and on the fate of Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews within the province. Various aspects of Ukrainian development receive special attention, and a major bibliographic essay completes the volume. Among the leading specialists represented are Peter Brock, Paul R. Magocsi, Ezra Mendelsohn, Ivan L. Rudnytsky, and Piotr Wandycz.

Patton takes up the twins’ story and their reckoning with their mixed-race, Black German identity to disrupt standard narratives around World War II, Black experiences in Germany, and race and adoption. Combining family interviews, historical artifacts, and autoethnographic reflection, Patton composes a new narrative of women and Black German children in the postwar era. In examining the systemic racism of Germany’s efforts to move children like Lore and Lilli out of the country—and the suppression of German women’s bodily autonomy—Patton amplifies the once unacknowledged identities of these Black German children to broaden our understanding of citizenship, racism, and sexism after World War II.

As the NATO Alliance enters its seventh decade, it finds itself involved in an array of military missions ranging from Afghanistan to Kosovo to Sudan. It also stands at the center of a host of regional and global partnerships. Yet, NATO has still to articulate a grand strategic vision designed to determine how, when, and where its capabilities should be used, the values underpinning its new missions, and its relationship to other international actors such as the European Union and the United Nations.

The drafting of a new strategic concept, begun during NATO’s 60th anniversary summit, presents an opportunity to shape a new transatlantic vision that is anchored in the liberal democratic principles so crucial to NATO’s successes during its Cold War years. Furthermore, that vision should be focused on equipping the Alliance to anticipate and address the increasingly global and less predictable threats of the post-9/11 world.

This volume brings together scholars and policy experts from both sides of the Atlantic to examine the key issues that NATO must address in formulating a new strategic vision. With thoughtful and reasoned analysis, it offers both an assessment of NATO’s recent evolution and an analysis of where the Alliance must go if it is to remain relevant in the twenty-first century.

NATO’s 2010 Strategic Concept officially broadened the alliance’s mission beyond collective defense, reflecting a peaceful Europe and changes in alliance activities. NATO had become an international security facilitator, a crisis-manager even outside Europe, and a liberal democratic club as much as a mutual-defense organization. However, Russia’s re-entry into great power politics has changed NATO’s strategic calculus.

Russia’s aggressive annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its ongoing military support for Ukrainian separatists dramatically altered the strategic environment and called into question the liberal European security order. States bordering Russia, many of which are now NATO members, are worried, and the alliance is divided over assessments of Russia’s behavior. Against the backdrop of Russia’s new assertiveness, an international group of scholars examines a broad range of issues in the interest of not only explaining recent alliance developments but also making recommendations about critical choices confronting the NATO allies. While a renewed emphasis on collective defense is clearly a priority, this volume’s contributors caution against an overcorrection, which would leave the alliance too inwardly focused, play into Russia’s hand, and exacerbate regional fault lines always just below the surface at NATO. This volume places rapid-fire events in theoretical perspective and will be useful to foreign policy students, scholars, and practitioners alike.

Challenging the conventional wisdom that French environmentalism can be dated only to the post-1945 period, Caroline Ford argues that a broadly shared environmental consciousness emerged in France much earlier. Natural Interests unearths the distinctive features of French environmentalism, in which a large and varied cast of social actors played a role. Besides scientific advances and colonial expansion, nostalgia for a vanishing pastoral countryside and anxiety over the pressing dangers of environmental degradation were important factors in the success of this movement.

Over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, war, political upheaval, and natural disasters—especially the devastating floods of 1856 and 1910 in Paris—caused growing worry over the damage wrought by deforestation, urbanization, and industrialization. The natural world took on new value for France’s urban bourgeoisie, as both a site of aesthetic longing and a destination for tourism. Not only naturalists and scientists but politicians, engineers, writers, and painters took up environmental causes.

Imperialism and international dialogue were also instrumental in shaping environmental consciousness, as the unfamiliar climates of France’s overseas possessions changed perceptions of the natural world and influenced conservationist policies. By the early twentieth century, France had adopted innovative environmental legislation, created national and urban parks and nature reserves, and called for international cooperation on environmental questions.

Is Italy il bel paese—the beautiful country—where tourists spend their vacations looking for art, history, and scenery? Or is it a land whose beauty has been cursed by humanity’s greed and nature’s cruelty? The answer is largely a matter of narrative and the narrator’s vision of Italy. The fifteen essays in Nature and History in Modern Italy investigate that nation’s long experience in managing domesxadtixadcated rather than wild natures and offer insight into these conflicting visions. Italians shaped their land in the most literal sense, producing the landscape, sculpting its heritage, embedding memory in nature, and rendering the two different visions inseparxadable. The interplay of Italy’s rich human history and its dramatic natural diversity is a subject with broad appeal to a wide range of readers.

The nineteenth century began with reverence for nature and ended with the apotheosis of art. In this wide-ranging excursion through the literature, visual arts, and natural sciences of the era from Wordsworth to Wilde, Carl Woodring traces shifting ideas and attitudes concerning nature, art, and the relations between the two.

The veneration of nature as aesthetic model and ethical norm was gradually eroded not least by the study of biology, which revealed organic nature to be wasteful and murderous. Darwin’s work verified the growing perception of nature as amoral by stressing the role of chance in natural selection, a further blow to trust in natural law. Once nature was not worth imitating, art by the century’s close could be an end to itself, free of responsibility to the natural.

The author examines individual works by Romantic and Victorian poets; narrative prose from James Hogg and Mary Shelley to Conrad, James, and Stevenson; painters from Wilkie through the Pre-Raphaelites to Whistler—all within such general contexts as the picturesque, the sublime, natural theology, romantic irony, romantic Hellenism, realism, photography, aestheticism, arts and crafts, art nouveau, and decadence. Although Woodring focuses on events, movements, and creative minds in England, he also draws upon a range of seminal figures from the Continent and the United States: Alexander von Humboldt, Delacroix, Thomas Cole, and Hawthorne are prominent examples. Nature into Art will fascinate scholars and amateurs of movements in literature, art, science, and cultural history in the Western world after 1780.

In the main, nineteenth-century German theologians paid little attention to natural science and especially eschewed philosophically popular yet naive versions of natural theology. Frederick Gregory shows that the loss of nature from theological discourse is only one reflection of the larger cultural change that marks the transition of European society from a nineteenth century to a twentieth-century mentality.

In examining this "loss of nature," Gregory refers to a larger shift in epistemological foundations--a shift felt in many fields ranging from art to philosophy to history to, of course, theology. Employing different understandings of the concept of truth as investigative tools, the author depicts varying theological responses to the growth of natural science in the nineteenth century. Although nature was lost to Germany's "premier" theologians, Gregory shows it was not lost to the majority of nineteenth century laypeople or to the various theologians who spoke for them. Like their twentieth-century counterparts, nineteenth-century creationists insisted on keeping nature at the heart of their systems; liberals welcomed natural knowledge with the conviction that there would be no contradiction if one really understood science or if one really understood religion; and pantheistic naturalists confidently discovered a religious vision in the wonder of the Darwinian universe. Gregory suggests that modern theologians who stand in the shadow of the loss of nature from theology are challenged to devise a way to recapture what others did not abandon.

In this study of natural science and religion in nineteenth century German-speaking Europe, Gregory examines an important but largely neglected topic that will interest an audience that includes historians of theology, historians of philosophy, cultural and intellectual historians of the German-speaking world, and historians of science.

"A compelling exposition of how authors, printers, booksellers and readers competed for power over the printed page. . . . The richness of Mr. Johns's book lies in the splendid detail he has collected to describe the world of books in the first two centuries after the printing press arrived in England."—Alberto Manguel, Washington Times

"[A] mammoth and stimulating account of the place of print in the history of knowledge. . . . Johns has written a tremendously learned primer."—D. Graham Burnett, New Republic

"A detailed, engrossing, and genuinely eye-opening account of the formative stages of the print culture. . . . This is scholarship at its best."—Merle Rubin, Christian Science Monitor

"The most lucid and persuasive account of the new kind of knowledge produced by print. . . . A work to rank alongside McLuhan."—John Sutherland, The Independent

"Entertainingly written. . . . The most comprehensive account available . . . well documented and engaging."—Ian Maclean, Times Literary Supplement

Initially conceived to exploit nature for the benefit of empire, the Gardens were part of a symbolic struggle by administrators, scientists, and gardeners to assert dominance within Southeast Asia’s tropical landscape, reflecting shifting understandings of power, science, and nature among local administrators and distant mentors in Britain. Consequently, as an outpost of imperial science, the Gardens were instrumental in the development of plantation crops, such as rubber and oil palm, which went on to shape landscapes across the globe. Since the independence of Singapore, the Gardens have played a role in the “greening” of the country and have been named as Singapore’s first World Heritage Site. Setting the Gardens alongside the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and botanic gardens in India, Ceylon, Mauritius, and the West Indies, Nature’s Colony provide the first in-depth look at the history of this influential institution.

In this groundbreaking study, Jacob A. Tropp explores the interconnections between negotiations over the environment and an emerging colonial relationship in a particular South African context—the Transkei—subsequently the largest of the notorious “homelands” under apartheid.

In the late nineteenth century, South Africa’s Cape Colony completed its incorporation of the area beyond the Kei River, known as the Transkei, and began transforming the region into a labor reserve. It simultaneously restructured popular access to local forests, reserving those resources for the benefit of the white settler economy. This placed new constraints on local Africans in accessing resources for agriculture, livestock management, hunting, building materials, fuel, medicine, and ritual practices.

Drawing from a diverse array of oral and written sources, Tropp reveals how bargaining over resources—between and among colonial officials, chiefs and headmen, and local African men and women—was interwoven with major changes in local political authority, gendered economic relations, and cultural practices as well as with intense struggles over the very meaning and scope of colonial rule itself.

Natures of Colonial Change sheds new light on the colonial era in the Transkei by looking at significant yet neglected dimensions of this history: how both “colonizing” and “colonized” groups negotiated environmental access and how such negotiations helped shape the broader making and meaning of life in the new colonial order.

This book highlights the indispensable role of rutters and ships’ logbooks in early modern navigation and knowledge production. Examining their legal, scientific, and cultural dimensions, it explores their evolution, influence on cartography, and impact beyond Europe, particularly in the Indian Ocean. With contributions from experts in the field, this volume underscores rutters as more than navigational aids—they were pivotal instruments in shaping global interconnectedness.

Essential reading for historians of science, maritime history, and globalization, this book reveals how these documents transformed Europe’s perception of a world connected by oceans.

The lasting impact of historic Portuguese voyages of discovery is unquestionable. The slave trade, the diaspora of the Sephardic Jews, and the intercontinental spread of plants and animals all make clear these voyages’ long-term global significance. Navigations reexamines these Portuguese quests by placing them in their medieval and Renaissance settings. It shows how these voyages grew out of a crusading ethos, as well as long-distance trade with Asia and Africa and developments in map-making and ship design. Malyn Newitt also narrates these voyages of discovery in the framework of Portuguese politics, describing the role of the Portuguese ruling dynasty—including its female members—in the flowering of the Portuguese Renaissance, the creation of the Renaissance state with its distinctive ideology, and in the cultural changes that took place within a wider European context.

The Nazi conscience is not an oxymoron. In fact, the perpetrators of genocide had a powerful sense of right and wrong, based on civic values that exalted the moral righteousness of the ethnic community and denounced outsiders.

Claudia Koonz's latest work reveals how racial popularizers developed the infrastructure and rationale for genocide during the so-called normal years before World War II. Her careful reading of the voluminous Nazi writings on race traces the transformation of longtime Nazis' vulgar anti-Semitism into a racial ideology that seemed credible to the vast majority of ordinary Germans who never joined the Nazi Party. Challenging conventional assumptions about Hitler, Koonz locates the source of his charisma not in his summons to hate, but in his appeal to the collective virtue of his people, the Volk.

From 1933 to 1939, Nazi public culture was saturated with a blend of racial fear and ethnic pride that Koonz calls ethnic fundamentalism. Ordinary Germans were prepared for wartime atrocities by racial concepts widely disseminated in media not perceived as political: academic research, documentary films, mass-market magazines, racial hygiene and art exhibits, slide lectures, textbooks, and humor. By showing how Germans learned to countenance the everyday persecution of fellow citizens labeled as alien, Koonz makes a major contribution to our understanding of the Holocaust.

The Nazi Conscience chronicles the chilling saga of a modern state so powerful that it extinguished neighborliness, respect, and, ultimately, compassion for all those banished from the ethnic majority.

What was life like under the Third Reich? What went on between parents and children? What were the prevailing attitudes about sex, morality, religion? How did workers perceive the effects of the New Order in the workplace? What were the cultural currents—in art, music, science, education, drama, and on the radio?

Professor Mosse’s extensive analysis of Nazi culture—groundbreaking upon its original publication in 1966—is now offered to readers of a new generation. Selections from newspapers, novellas, plays, and diaries as well as the public pronouncements of Nazi leaders, churchmen, and professors describe National Socialism in practice and explore what it meant for the average German.

By recapturing the texture of culture and thought under the Third Reich, Mosse’s work still resonates today—as a document of everyday life in one of history’s darkest eras and as a living memory that reminds us never to forget.

This volume brings together a hitherto scattered and inaccessible body of material crucial to the understanding of the evolution of Nazi political thought. Before the publication of this volume, scholars had virtually ignored the extensive writings and programs published by leading Nazi ideologues before 1933. Barbara Miller Lane and Leila J. Rupp have collected the political writings of Nazi theorists—Dietrich Eckart, Alfred Rosenberg, Gottfried Feder, Joseph Goebbels, Gregor and Otto Strasser, Heinrich Himmler, and Richard Walther Darré—during the period before the National Socialists came to power. The Strassers are given considerable space because of their great intellectual importance within the party before 1933. In commentary by the editors, the significance of each Nazi theorist is weighed and evaluated at each stage of the history of the party.

Lane and Rupp conclude that Nazi ideology, before 1933 at least, was not a consistent whole but a doctrine in the process of rapid development to which new ideas were continually introduced. By the time the Nazis came to power, however, a group of interrelated assertions and official promises had been made to party followers and to the public. Hitler and the Third Reich had to accommodate this ideology, even when not implementing it. Hitler’s role in the development of Nazi ideology, interpreted here as a very permissive one, is thoroughly assessed. His own writings, however, have been omitted since they are readily available elsewhere.

The twenty-eight documents included in this book illustrate themes and phases in Nazi ideology which are discussed in the introduction and the detailed prefatory notes. Long selections, as often as possible full-length, are provided to allow the reader to follow the arguments. Each selection is accompanied by an introductory note and annotations which clarify its relationship to other works of the author and other writings of the period. Also included are original translations of the “Twenty-Five Points” and a number of little-known official party statements.

The Faustian bargain—in which an individual or group collaborates with an evil entity in order to obtain knowledge, power, or material gain—is perhaps best exemplified by the alliance between world-renowned human geneticists and the Nazi state. Under the swastika, German scientists descended into the moral abyss, perpetrating heinous medical crimes at Auschwitz and at euthanasia hospitals. But why did biomedical researchers accept such a bargain?

The Nazi Symbiosis offers a nuanced account of the myriad ways human heredity and Nazi politics reinforced each other before and during the Third Reich. Exploring the ethical and professional consequences for the scientists involved as well as the political ramifications for Nazi racial policies, Sheila Faith Weiss places genetics and eugenics in their larger international context. In questioning whether the motives that propelled German geneticists were different from the compromises that researchers from other countries and eras face, Weiss extends her argument into our modern moment, as we confront the promises and perils of genomic medicine today.

In 2006 a long-forgotten canister of film was discovered in a church in Devon, a county located in the southwestern corner of the United Kingdom. No one knew how it had gotten there, but its contents were tantalizing—the grainy black and white footage showed members of the German SS and police building a road in Ukraine and Crimea in 1943. The BBC caused a sensation when it aired the footage, but the film gave few clues to the protagonists or their task.

Following France’s crushing defeat in June 1940, the Nazis moved forward with plans to reorganize a European continent now largely under Hitler’s heel. While Germany’s military power would set the agenda, several among the Nazi elite argued that permanent German hegemony required something more: a pan-European cultural empire that would crown Hitler’s wartime conquests. At a time when the postwar European project is under strain, Benjamin G. Martin brings into focus a neglected aspect of Axis geopolitics, charting the rise and fall of Nazi-fascist “soft power” in the form of a nationalist and anti-Semitic new ordering of European culture.

As early as 1934, the Nazis began taking steps to bring European culture into alignment with their ideological aims. In cooperation and competition with Italy’s fascists, they courted filmmakers, writers, and composers from across the continent. New institutions such as the International Film Chamber, the European Writers Union, and the Permanent Council of composers forged a continental bloc opposed to the “degenerate” cosmopolitan modernism that held sway in the arts. In its place they envisioned a Europe of nations, one that exalted traditionalism, anti-Semitism, and the Volk. Such a vision held powerful appeal for conservative intellectuals who saw a European civilization in decline, threatened by American commercialism and Soviet Bolshevism.

Taking readers to film screenings, concerts, and banquets where artists from Norway to Bulgaria lent their prestige to Goebbels’s vision, Martin follows the Nazi-fascist project to its disastrous conclusion, examining the internal contradictions and sectarian rivalries that doomed it to failure.

In A Necessary Luxury: Tea in Victorian England, Julie E. Fromer analyzes tea histories, advertisements, and nine Victorian novels, including Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Wuthering Heights, and Portrait of a Lady. Fromer demonstrates how tea functions within the literature as an arbiter of taste and middle-class respectability, aiding in the determination of class status and moral position. She reveals the way in which social identity and character are inextricably connected in Victorian ideology as seen through the ritual of tea.

Drawing from the fields of literary studies, cultural studies, history, and anthropology, A Necessary Luxury offers in-depth analysis of both visual and textual representations of the commodity and the ritual that was tea in nineteenth-century England.

This book examines the ways in which people wrote about and engaged with infertility in the German Middle Ages. Striking differences emerge across the vernacular stories, legends, and romances concerned. For some, childlessness is a huge problem, for others, a high ideal. Regina Toepfer considers the reasons for these differences, and how ideas changed over the period, revealing different narrative patterns that shape stories of childlessness right up to the present day.

These range from the late fulfilment of the longing to have children, assisted by divine or demonic help; through social and religious alternatives to parenthood; to the conscious decision to remain childless and achieve happiness through partnership alone. Bringing German source material to an English readership for the first time, this book provides fresh insights on childlessness that engage with current debates about sperm donation, adoption, and being childfree.

The two case studies included in this book (dealing with the Football World Cups of 1994 and 2002, and the general elections of 1996 and 2000) examine competing discourses of Spain, Catalonia and their national identities, as constructed in the Spanish press. The conservative discourse offers traditional and unified images of Spain close to the stereotype, whereas more liberal visions of the country regard 'Europeanism' and 'reason' (not 'passive') as the values Spain should aspire to. From a peripheral perspective, Catalan self-definition is of a people that is hardworking, thoughtful, truly European, and different from the rest of the Spaniards.

However, these differences between the discourses are not always so clear-cut. Central to Negotiating Spain and Catalonia is the idea of the constant renegotiation of Spanish and Catalan identities in order to adapt them to the political circumstance: both case studies show how radically different narratives of Spanishness and Catalanicity offered in the turbulent political past tend to merge into the more tranquil present.

There have been countless scripture-based studies of the three “religions of the book,” but Nirenberg goes beyond those to pay close attention to how the three religious neighbors loved, tolerated, massacred, and expelled each other—all in the name of God—in periods and places both long ago and far away. Nirenberg argues that the three religions need to be studied in terms of how each affected the development of the others over time, their proximity of religious and philosophical thought as well as their overlapping geographies, and how the three “neighbors” define—and continue to define—themselves and their place in terms of one another. From dangerous attractions leading to interfaith marriage; to interreligious conflicts leading to segregation, violence, and sometimes extermination; to strategies for bridging the interfaith gap through language, vocabulary, and poetry, Nirenberg aims to understand the intertwined past of the three faiths as a way for their heirs to produce the future—together.

"This is a fascinating local story with major implications for studies of nationalism and regional identities throughout Europe more generally."

---Dennis Sweeney, University of Alberta

"James Bjork has produced a finely crafted, insightful, indeed, pathbreaking study of the interplay between religious and national identity in late nineteenth-century Central Europe."

---Anthony Steinhoff, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

Neither German nor Pole examines how the inhabitants of one of Europe's most densely populated industrial districts managed to defy clear-cut national categorization, even in the heyday of nationalizing pressures at the turn of the twentieth century. As James E. Bjork argues, the "civic national" project of turning inhabitants of Upper Silesia into Germans and the "ethnic national" project of awakening them as Poles both enjoyed successes, but these often canceled one another out, exacerbating rather than eliminating doubts about people's national allegiances. In this deadlock, it was a different kind of identification---religion---that provided both the ideological framework and the social space for Upper Silesia to navigate between German and Polish orientations. A fine-grained, microhistorical study of how confessional politics and the daily rhythms of bilingual Roman Catholic religious practice subverted national identification, Neither German nor Pole moves beyond local history to address broad questions about the relationship between nationalism, religion, and modernity.

The rise of British neoliberalism—a renewed emphasis on privatization and market-oriented economics—over the last fifty years is often characterized as the product of right-wing political economists, think tanks, and politicians. The Neoliberal Age? argues that this pat narrative ignores broader forces in British left-wing culture that collaborated to transform twentieth-century social life. Through a variety of case studies, the authors demonstrate that our austere, individualistic age emerged from more complex sociopolitical negotiations than typically described.

Between 1917 and 1921, the Makhnovists fought German and Austrian invaders, reactionary monarchist forces, Ukrainian nationalists and sometimes the Bolsheviks themselves. Drawing upon anarchist ideology, the Makhnovists gathered widespread support amongst the Ukrainian peasantry, taking up arms when under attack and playing a significant role - in temporary alliance with the Red Army - in the defeats of the White Generals Denikin and Wrangel. Often dismissed as a kulak revolt, or a manifestation of Ukrainian nationalism, Colin Darch analyses the successes and failures of the Makhnovist movement, emphasising its revolutionary character.

Over 100 years after the revolutions, this book reveals a lesser known side of 1917, contributing both to histories of the period and broadening the narrative of 1917, whilst enriching the lineage of anarchist history.

Between 1917 and 1921, the Makhnovists fought German and Austrian invaders, reactionary monarchist forces, Ukrainian nationalists and sometimes the Bolsheviks themselves. Drawing upon anarchist ideology, the Makhnovists gathered widespread support amongst the Ukrainian peasantry, taking up arms when under attack and playing a significant role - in temporary alliance with the Red Army - in the defeats of the White Generals Denikin and Wrangel. Often dismissed as a kulak revolt, or a manifestation of Ukrainian nationalism, Colin Darch analyzes the successes and failures of the Makhnovist movement, emphasizing its revolutionary character.

Over 100 years after the revolutions, this book reveals a lesser known side of 1917, contributing both to histories of the period and broadening the narrative of 1917, whilst enriching the lineage of anarchist history.

Nether World presents a rich, often humorous glimpse into everyday life in Victorian London through a revealing account of nineteenth-century police courts. People of all classes brought complaints to this court about those who had hurt, abused, or stolen from them—drunks, pickpockets, wife-beaters, and fraudsters—who were each in their turn judged by magistrates wielding broad summary powers. Delving into underexamined court records and the pages of a fast-developing newspaper industry, Drew D. Gray offers a fresh description of a vibrant, ever-changing metropolis and considers ongoing issues such as poverty, homelessness, violence, substance abuse, prostitution, and—of course—crime.

“The Holocaust…was beyond the belief and comprehension of almost all people living at the time… [It] was a notion so alien to the human mind, and even so gruesome, so new, that the instinctive, indeed the natural reaction, of most people was: ‘It can’t be true.’” Thus writes the Netherlands’ preeminent historian in this memoir and account of war and genocide. Concentrating on three central topics—the Holocaust, the resistance, and the leadership of Queen Wilhelmina—Louis de Jong recaptures the wartime experience of Holland and explains some of the more anomalous happenings.

The swift, devastating conquest of the Netherlands by the Nazis made possible three appalling weapons of control over the Dutch: fear, the dividing of people, and deception. Intending to absorb Holland into the German empire, the Nazis planned to exploit the country economically, purge it of Jews, and prevent any assistance to the Allies. They succeeded only too well. The Dutch provided substantial economic support to the Nazis, though they did so to keep men employed at home rather than being sent to work in Germany. Although the Jewish Council, which cooperated with the Nazis, assisted in the deportation of thousands of Jews to concentration camps, such zealousness reflected the innocence of an assimilated people in the face of a hitherto unexperienced, virulent antisemitism.

It was almost inconceivable that a resistance movement could operate in flat open country; nevertheless there was such a movement. De Jong recaptures a terrible time and the grim fate of a nation accustomed to centuries of peace and suddenly plunged into the Nazis’ obscene war.

Linda M. Martz focuses on families that were immersed in the worlds of business and finance. They formed the backbone of the trade industry and, during the economic expansion of the sixteenth century, enjoyed a high degree of affluence. The seventeenth century, however, brought harder times. How these families rose to positions of commercial eminence and then adapted to this economic downturn is one of the questions addressed in this insightful book.

A Network of Converso Families in Early Modern Toledo relies heavily on archival evidence--notarial, parish, and city records--that offers new insights into the families' histories. Business endeavors, marriage alliances, involvement in local politics, and the pursuit of improved social status are all subjected to Martz's keen analysis.

These families appear to have been well integrated into their contemporary society; aside from their business and financial activities, many were members of the city's governing council. But how well did they integrate with the lower classes? Assimilating minorities in the majority culture is a task that confronts most modern societies, so the experience of Spain and this particular minority may serve as an example of how earlier societies viewed and confronted this challenge.

This book will appeal to historians of medieval and Renaissance Spain and those interested in the Inquisition's effect on Renaissance Spain. It will also prove to be indispensable for those interested in the history of the Jewish race, as well as for those pursuing the question of marginalization.

Linda M. Martz is an independent historian as well as a freelance editor and writer.

Opera’s role in shaping Italian identity has long fascinated both critics and scholars. Whereas the romance of the Risorgimento once spurred analyses of how individual works and styles grew out of and fostered specifically “Italian” sensibilities and modes of address, more recently scholars have discovered the ways in which opera has animated Italians’ social and cultural life in myriad different local contexts.

In Networking Operatic Italy, Francesca Vella reexamines this much-debated topic by exploring how, where, and why opera traveled on the mid-nineteenth-century peninsula, and what this mobility meant for opera, Italian cities, and Italy alike. Focusing on the 1850s to the 1870s, Vella attends to opera’s encounters with new technologies of transportation and communication, as well as its continued dissemination through newspapers, wind bands, and singing human bodies. Ultimately, this book sheds light on the vibrancy and complexity of nineteenth-century Italian operatic cultures, challenging many of our assumptions about an often exoticized country.

“The New Berlin is a notable contribution to human geography and to the interdisciplinary literature on social memory and place making. Till’s methods and scholarship have provided the conceptual groundwork for the exploration and development of place making, social memory, and spatial haunting through the particular practices and politics of the new Berlin. Her readable style is marked by a narrative economy in which every word and sentence serves the larger purposes of the book. I recommend this book to anyone—student, scholar, or practitioner—who is interested in the social dynamics of memory formation and place making.” —The Professional Geographer

“This book is a well-written ‘first-hand’ account, though it also thoroughly covers academic literature, contemporary news accounts, and archival records.” —German Studies Review

“Karen E. Till's The New Berlin describes the modern metropolis and the ghosts of the past that it has to deal with.” —German World

“Well illustrated and copiously footnoted, this is a cutting-edge study of the power of identity-construction/analysis. Highly recommended.” —CHOICE

Contributors. Alfredo Ávila, Roberto Breña, Sarah C. Chambers, Jordana Dym, Carolyn Fick, Erick Langer, Adam Rothman, David Sartorius, Kirsten Schultz, John Tutino

This companion to the two-volume Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library edition and translation of the Histories by Laonikos Chalkokondyles is the first book-length investigation of an author who has been poorly studied. Providing biographical and intellectual context for Laonikos, Anthony Kaldellis shows how the author synthesized his classical models to fashion his own distinctive voice and persona as a historian.

Indebted to his teacher Plethon for his global outlook, Laonikos was one of the first historians to write with a pluralist’s sympathy for non-Greek ethnic groups, including Islamic ones. His was the first secular and neutral account of Islam written in Greek. Kaldellis deeply explores the ethnic dynamics that explicitly and implicitly undergird the Histories, which recount the rise of the Ottoman empire and the decline of the Byzantine empire, all in the context of expanding western power. Writing at once in antique and contemporary modes, Laonikos transformed “barbarian” oral traditions into a classicizing historiography that was both Greek and Ottoman in outlook.

Showing that he was instrumental in shifting the self-definition of his people from Roman to the Western category of “Greek,” Kaldellis provides a stimulating account of the momentous transformations of the mid-fifteenth century.

Designed for the general reader, this splendid introduction to French literature from 842 A.D.—the date of the earliest surviving document in any Romance language—to the present decade is the most compact and imaginative single-volume guide available in English to the French literary tradition. In fact, no comparable work exists in either language. It is not the customary inventory of authors and titles but rather a collection of wide-angled views of historical and cultural phenomena. It sets before us writers, public figures, criminals, saints, and monarchs, as well as religious, cultural, and social revolutions. It gives us books, paintings, public monuments, even TV shows.

Written by 164 American and European specialists, the essays are introduced by date and arranged in chronological order, but here ends the book’s resemblance to the usual history of literature. Each date is followed by a headline evoking an event that indicates the chronological point of departure. Usually the event is literary—the publication of an original work, a journal, a translation, the first performance of a play, the death of an author—but some events are literary only in terms of their repercussions and resonances. Essays devoted to a genre exist alongside essays devoted to one book, institutions are presented side by side with literary movements, and large surveys appear next to detailed discussions of specific landmarks.

No article is limited to the “life and works” of a single author. Proust, for example, appears through various lenses: fleetingly, in 1701, apropos of Antoine Galland’s translation of The Thousand and One Nights; in 1898, in connection with the Dreyfus Affair; in 1905, on the occasion of the law on the separation of church and state; in 1911, in relation to Gide and their different treatments of homosexuality; and at his death in 1922.

Without attempting to cover every author, work, and cultural development since the Serments de Strasbourg in 842, this history succeeds in being both informative and critical about the more than 1,000 years it describes. The contributors offer us a chance to appreciate not only French culture but also the major critical positions in literary studies today. A New History of French Literature will be essential reading for all engaged in the study of French culture and for all who are interested in it. It is an authoritative, lively, and readable volume.

The revolutionary spirit that animates the culture of the Germans has been alive for at least twelve centuries, far longer than the dramatically fragmented and reshaped political entity known as Germany. German culture has been central to Europe, and it has contributed the transforming spirit of Lutheran religion, the technology of printing as a medium of democracy, the soulfulness of Romantic philosophy, the structure of higher education, and the tradition of liberal socialism to the essential character of modern American life.

In this book leading scholars and critics capture the spirit of this culture in some 200 original essays on events in German literary history. Rather than offering a single continuous narrative, the entries focus on a particular literary work, an event in the life of an author, a historical moment, a piece of music, a technological invention, even a theatrical or cinematic premiere. Together they give the reader a surprisingly unified sense of what it is that has allowed Meister Eckhart, Hildegard of Bingen, Luther, Kant, Goethe, Beethoven, Benjamin, Wittgenstein, Jelinek, and Sebald to provoke and enchant their readers. From the earliest magical charms and mythical sagas to the brilliance and desolation of 20th-century fiction, poetry, and film, this illuminating reference book invites readers to experience the full range of German literary culture and to investigate for themselves its disparate and unifying themes.

Contributors include: Amy M. Hollywood on medieval women mystics, Jan-Dirk Müller on Gutenberg, Marion Aptroot on the Yiddish Renaissance, Emery Snyder on the Baroque novel, J. B. Schneewind on Natural Law, Maria Tatar on the Grimm brothers, Arthur Danto on Hegel, Reinhold Brinkmann on Schubert, Anthony Grafton on Burckhardt, Stanley Corngold on Freud, Andreas Huyssen on Rilke, Greil Marcus on Dada, Eric Rentschler on Nazi cinema, Elisabeth Young-Bruehl on Hannah Arendt, Gordon A. Craig on Günter Grass, Edward Dimendberg on Holocaust memorials.

After the Treaty of Paris ended the Seven Years’ War in 1763, British America stretched from Hudson Bay to the Florida Keys, from the Atlantic coast to the Mississippi River, and across new islands in the West Indies. To better rule these vast dominions, Britain set out to map its new territories with unprecedented rigor and precision. Max Edelson’s The New Map of Empire pictures the contested geography of the British Atlantic world and offers new explanations of the causes and consequences of Britain’s imperial ambitions in the generation before the American Revolution.

Under orders from King George III to reform the colonies, the Board of Trade dispatched surveyors to map far-flung frontiers, chart coastlines in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, sound Florida’s rivers, parcel tropical islands into plantation tracts, and mark boundaries with indigenous nations across the continental interior. Scaled to military standards of resolution, the maps they produced sought to capture the essential attributes of colonial spaces—their natural capacities for agriculture, navigation, and commerce—and give British officials the knowledge they needed to take command over colonization from across the Atlantic.

Britain’s vision of imperial control threatened to displace colonists as meaningful agents of empire and diminished what they viewed as their greatest historical accomplishment: settling the New World. As London’s mapmakers published these images of order in breathtaking American atlases, Continental and British forces were already engaged in a violent contest over who would control the real spaces they represented.

Accompanying Edelson’s innovative spatial history of British America are online visualizations of more than 250 original maps, plans, and charts.

This study examines the history of Zionist academic Orientalism—referred to throughout as Oriental studies, the term contemporary English speakers would have used—in light of its German-Jewish background, as a history of knowledge transfer stretching along an axis from Germany to Palestine. The transfer, which took place primarily during the 1920s and 1930s, involved questions about the re-establishment, far from Germany, of a field of knowledge with deep German roots. Like other German-Jewish scholars arriving in Palestine at the time, some of the Orientalist agents of transfer did so out of Zionist conviction as olim (immigrants making aliyah, or literally “ascending” to the homeland), while others joined them later as refugees from Nazi Germany; both groups were integrated into the institutional apparatus of the Hebrew University. Unlike other fields of knowledge or professions, however, the transfer of Orientalist knowledge was unique in that the axis involved an essential change in the nature of its encounter with the Orient: from a textual-scientific encounter at German universities, largely disconnected from contemporary issues to a living, substantive, and unmediated encounter with an essentially Arab region—and the escalating Jewish-Arab conflict in the background. Within the new context, German-Jewish Orientalist expertise was charged with political and cultural significance it had not previously faced, fundamentally influencing the course of the discipline’s development in Palestine and Israel.

The New Prometheans traces the evolution of psychical research through the intertwining biographies of four men: chemist Sir William Crookes, depth psychologist Frederic Myers, ether physicist Sir Oliver Lodge, and anthropologist Andrew Lang. All past presidents of the society, these men brought psychical research beyond academic circles and into the public square, making it part of a shared, far-reaching examination of science and society. By layering their papers, textbooks, and lectures with more intimate texts like diaries, letters, and literary compositions, Courtenay Raia returns us to a critical juncture in the history of secularization, the last great gesture of reconciliation between science and sacred truths.

In the fourth volume of the New Technologies in Medieval and Renaissance Studies series, volume editors Tassie Gniady, Kris McAbee, and Jessica Murphy bring together some of the best work from the New Technologies in Medieval and Renaissance Studies panels at the Renaissance Society of America (RSA) annual meetings for the years 2004–2010. These essays demonstrate a dedication to grounding the use of “newest” practices in the theories of the early modern period. At the same time, the essays are interested in the moment—the needs of scholars then, the theories of media that informed current understanding, and the tools used to conduct studies.

The New Testament lay at the center of Byzantine Christian thought and practice. But codices and rolls were neither the sole way—nor most important way—the Byzantines understood the New Testament. Lectionaries apportioned much of its contents over the course of the liturgical calendar; its narratives structured the experience of liturgical time and shaped the nature of Christian preaching, throughout Byzantine history. A successor to The Old Testament in Byzantium (2010), this book asks: What was the New Testament for Byzantine Christians? What of it was known, how, when, where, and by whom? How was this knowledge mediated through text, image, and rite? What was the place of these sacred texts in Byzantine arts, letters, and thought?

Authors draw upon the current state of textual scholarship and explore aspects of the New Testament, particularly as it was read, heard, imaged, and imagined in lectionaries, hymns, homilies, saints’ lives, and as it was illustrated in miniatures and monuments. Framing theological inquiry, ecclesiastical controversy, and political thought, the contributions here help develop our understanding of the New Testament and its varied reception over the long history of Byzantium.

The discovery of the New World was initially a cause for celebration. But the vast amounts of gold that Columbus and other explorers claimed from these lands altered Spanish society. The influx of such wealth contributed to the expansion of the Spanish empire, but also it raised doubts and insecurities about the meaning and function of money, the ideals of court and civility, and the structure of commerce and credit. New World Gold shows that, far from being a stabilizing force, the flow of gold from the Americas created anxieties among Spaniards and shaped a host of distinct behaviors, cultural practices, and intellectual pursuits on both sides of the Atlantic.

Elvira Vilches examines economic treatises, stories of travel and conquest, moralist writings, fiction, poetry, and drama to reveal that New World gold ultimately became a problematic source of power that destabilized Spain’s sense of trust, truth, and worth. These cultural anxieties, she argues, rendered the discovery of gold paradoxically disastrous for Spanish society. Combining economic thought, social history, and literary theory in trans-Atlantic contexts, New World Gold unveils the dark side of Spain’s Golden Age.

Newman University Church, Dublin charts the first ever analysis of University Church’s significance within the history of Victorian revivalist architecture. Author Niamh Bhalla explores the relationship between the church’s context as the first Catholic university in Ireland and the ambiguity of its “early Christian” style, providing an effective lens to understand the architectural revivalism of the nineteenth century, particularly basilican and Byzantine revivalist architectures in the British Isles.

Winner of the Barclay Book Prize, German Studies Association

Winner of the Gomory Prize in Business History, American Historical Association and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation

Winner of the Fraenkel Prize, Wiener Library for the Study of Holocaust and Genocide

Honorable Mention, European Studies Book Award, Council for European Studies

To control information is to control the world. This innovative history reveals how, across two devastating wars, Germany attempted to build a powerful communication empire—and how the Nazis manipulated the news to rise to dominance in Europe and further their global agenda.

Information warfare may seem like a new feature of our contemporary digital world. But it was just as crucial a century ago, when the great powers competed to control and expand their empires. In News from Germany, Heidi Tworek uncovers how Germans fought to regulate information at home and used the innovation of wireless technology to magnify their power abroad.

Tworek reveals how for nearly fifty years, across three different political regimes, Germany tried to control world communications—and nearly succeeded. From the turn of the twentieth century, German political and business elites worried that their British and French rivals dominated global news networks. Many Germans even blamed foreign media for Germany’s defeat in World War I. The key to the British and French advantage was their news agencies—companies whose power over the content and distribution of news was arguably greater than that wielded by Google or Facebook today. Communications networks became a crucial battleground for interwar domestic democracy and international influence everywhere from Latin America to East Asia. Imperial leaders, and their Weimar and Nazi successors, nurtured wireless technology to make news from Germany a major source of information across the globe. The Nazi mastery of global propaganda by the 1930s was built on decades of Germany’s obsession with the news.

News from Germany is not a story about Germany alone. It reveals how news became a form of international power and how communications changed the course of history.

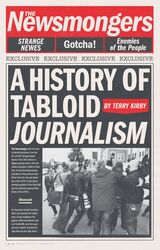

The Newsmongers unfolds the seedy history of tabloid journalism, from the first printed “Strange Newes” sheets of the sixteenth century to the sensationalism of today’s digital age. The narrative weaves from Regency gossip writers through New York’s “yellow journalism” battles to the “sex and sleaze” Sun of the 1970s; and from the Brexit-backing populism of the Daily Mail to the celebrity-obsessed Mail Online of the 2000s. Colorful figures such as Daniel Defoe, Lord Northcliffe, Joseph Pulitzer, William Randolph Hearst, Hugh Cudlipp, Rupert Murdoch, and Robert Maxwell are brought to vivid life.

From scandalous confessions to the Leveson Inquiry into the behavior of the British press, the book explores journalists’ unscrupulous methods, taking in phone hacking, privacy breaches, and bribery. And now, in the digital era, The Newsmongers shows how popular journalism has succumbed to so-called churnalism while a certain royal is seeking revenge on the tabloids today.

A comprehensive study of public culture, The Newton Wars and the Beginning of the French Enlightenment digsbelow the surface of the commonplace narratives that link Newton with Enlightenment thought to examine the actual historical changes that brought them together in eighteenth-century time and space. Drawing on the full range of early modern scientific sources, from studied scientific treatises and academic papers to book reviews, commentaries, and private correspondence, J. B. Shank challenges the widely accepted claim that Isaac Newton’s solitary genius is the reason for his iconic status as the father of modern physics and the philosophemovement.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press