41 start with S start with S

"In Science as a Process, [David Hull] argues that the tension between cooperation and competition is exactly what makes science so successful. . . . Hull takes an unusual approach to his subject. He applies the rules of evolution in nature to the evolution of science, arguing that the same kinds of forces responsible for shaping the rise and demise of species also act on the development of scientific ideas."—Natalie Angier, New York Times Book Review

"By far the most professional and thorough case in favour of an evolutionary philosophy of science ever to have been made. It contains excellent short histories of evolutionary biology and of systematics (the science of classifying living things); an important and original account of modern systematic controversy; a counter-attack against the philosophical critics of evolutionary philosophy; social-psychological evidence, collected by Hull himself, to show that science does have the character demanded by his philosophy; and a philosophical analysis of evolution which is general enough to apply to both biological and historical change."—Mark Ridley, Times Literary Supplement

"Hull is primarily interested in how social interactions within the scientific community can help or hinder the process by which new theories and techniques get accepted. . . . The claim that science is a process for selecting out the best new ideas is not a new one, but Hull tells us exactly how scientists go about it, and he is prepared to accept that at least to some extent, the social activities of the scientists promoting a new idea can affect its chances of being accepted."—Peter J. Bowler, Archives of Natural History

"I have been doing philosophy of science now for twenty-five years, and whilst I would never have claimed that I knew everything, I felt that I had a really good handle on the nature of science, Again and again, Hull was able to show me just how incomplete my understanding was. . . . Moreover, [Science as a Process] is one of the most compulsively readable books that I have ever encountered."—Michael Ruse, Biology and Philosophy

The surprising history of the scientific method—from an evolutionary account of thinking to a simple set of steps—and the rise of psychology in the nineteenth century.

The idea of a single scientific method, shared across specialties and teachable to ten-year-olds, is just over a hundred years old. For centuries prior, science had meant a kind of knowledge, made from facts gathered through direct observation or deduced from first principles. But during the nineteenth century, science came to mean something else: a way of thinking.

The Scientific Method tells the story of how this approach took hold in laboratories, the field, and eventually classrooms, where science was once taught as a natural process. Henry M. Cowles reveals the intertwined histories of evolution and experiment, from Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection to John Dewey’s vision for science education. Darwin portrayed nature as akin to a man of science, experimenting through evolution, while his followers turned his theory onto the mind itself. Psychologists reimagined the scientific method as a problem-solving adaptation, a basic feature of cognition that had helped humans prosper. This was how Dewey and other educators taught science at the turn of the twentieth century—but their organic account was not to last. Soon, the scientific method was reimagined as a means of controlling nature, not a product of it. By shedding its roots in evolutionary theory, the scientific method came to seem far less natural, but far more powerful.

This book reveals the origin of a fundamental modern concept. Once seen as a natural adaptation, the method soon became a symbol of science’s power over nature, a power that, until recently, has rarely been called into question.

Indeed scorpions are older than dinosaurs. An ancient arthropod, their form—notable for its pair of pincers and an elegant tail that holds a menacing stinger high in the air in a permanent striking position—hasn’t changed since prehistoric times, though today there are some 1700 different species. Throughout our existence scorpions have served as a powerful cultural and religious symbol—sometimes dangerous, sometimes protecting—from the Egyptian goddess Serket to Zodiac astrology to folk medicine. A fascinating tour that takes us from the art of North Africa to the American Civil War to the markets of Beijing, Scorpion is an homage to one of earth’s oldest residents.

"In Sewall Wright and Evolutionary Biology . . . Provine has produced an intellectual biography which serves to chart in considerable detail both the life and work of one man and the history of evolutionary theory in the middle half of this century. Provine is admirably suited to his task. . . . The resulting book is clearly a labour of love which will be of great interest to those who have a mature interest in the history of evolutionary theory."-John Durant, ;ITimes Higher Education Supplement;X

Conflict between males and females over reproduction is ubiquitous in nature due to fundamental differences between the sexes in reproductive rates and investment in offspring. In only a few species, however, do males strategically employ violence to control female sexuality. Why are so many of these primates? Why are females routinely abused in some species, but never in others? And can the study of such unpleasant behavior by our closest relatives help us to understand the evolution of men’s violence against women?

In the first systematic attempt to assess and understand primate male aggression as an expression of sexual conflict, the contributors to this volume consider coercion in direct and indirect forms: direct, in overcoming female resistance to mating; indirect, in decreasing the chance the female will mate with other males. The book presents extensive field research and analysis to evaluate the form of sexual coercion in a range of species—including all of the great apes and humans—and to clarify its role in shaping social relationships among males, among females, and between the sexes.

As Darwin first pointed out, two distinct evolutionary processes have contributed to the diversity of form and function in plants and animals: natural selection and sexual selection. In this book William Eberhard presents a new theory that explains male genitalic evolution as a result of sexual selection. From flatworms to fish, from moths to rodents, animal genitalia display an extraordinary variety of baroque morphologies. Not only are the forms varied, they have diverged rapidly in the course of evolution.

Why such strange forms and such rapid divergence? These questions have puzzled evolutionary biologists and animal taxonomists for over a century, and several hypotheses have been proposed. Eberhard shows that none of the explanations is adequate and proposes a new hypothesis. He views genitalia as courtship devices that function in the competition for mates by influencing the females' choices of fathers for their offspring. To the extent that male genitalic structures affect female choices, male genitalia are subject to the same type of runaway selection as that on structures, such as the peacock's tail, used in precopulatory courtship.

Eberhard's hypothesis can explain the fact that in a vast range of animals, from nematodes to mammals, male genitalia tend to be more complex than female genitalia, are often more elaborate than would be required for simply introducing sperm into the female's body, and have diverged rapidly and are thus highly species-specific in form. Although the emphasis is on theoretical explanations, many examples are presented of the vast diversity of animal genitalia: squids with arms whose tips break off and swim around inside the female after introducing an explosive, grenade-like sperm packet into her; flatworms that have rows of penes despite the presence of only a single female aperture; damselflies that give their mates contraceptive douches prior to inseminating them; and female seahorses with penes.

Shaking the Tree brings together nineteen review articles written for Nature over the past decade by many of the major figures in paleontology and evolution, from Stephen Jay Gould to Simon Conway Morris. Each article is brief, accessible, and opinionated, providing "shoot from the hip" accounts of the latest news and debates. Topics covered include major extinction events, homeotic genes and body plans, the origin and evolution of the primates, and reconstructions of phylogenetic trees for a wide variety of groups. The editor, Henry Gee, gives new commentary and updated references.

Shaking the Tree is a one-stop resource for engaging overviews of the latest research in the history of life on Earth.

Raff uses the evolution of animal body plans to exemplify the interplay between developmental mechanisms and evolutionary patterns. Animal body plans emerged half a billion years ago. Evolution within these body plans during this span of time has resulted in the tremendous diversity of living animal forms.

Raff argues for an integrated approach to the study of the intertwined roles of development and evolution involving phylogenetic, comparative, and functional biology. This new synthesis will interest not only scientists working in these areas, but also paleontologists, zoologists, morphologists, molecular biologists, and geneticists.

The propensity to make music is the most mysterious, wonderful, and neglected feature of humankind: this is where Steven Mithen began, drawing together strands from archaeology, anthropology, psychology, neuroscience--and, of course, musicology--to explain why we are so compelled to make and hear music. But music could not be explained without addressing language, and could not be accounted for without understanding the evolution of the human body and mind. Thus Mithen arrived at the wildly ambitious project that unfolds in this book: an exploration of music as a fundamental aspect of the human condition, encoded into the human genome during the evolutionary history of our species.

Music is the language of emotion, common wisdom tells us. In The Singing Neanderthals, Mithen introduces us to the science that might support such popular notions. With equal parts scientific rigor and charm, he marshals current evidence about social organization, tool and weapon technologies, hunting and scavenging strategies, habits and brain capacity of all our hominid ancestors, from australopithecines to Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis and Neanderthals to Homo sapiens--and comes up with a scenario for a shared musical and linguistic heritage. Along the way he weaves a tapestry of cognitive and expressive worlds--alive with vocalized sound, communal mimicry, sexual display, and rhythmic movement--of various species.

The result is a fascinating work--and a succinct riposte to those, like Steven Pinker, who have dismissed music as a functionless evolutionary byproduct.

In this ambitious and unusual work, evolutionary biologist Gordon H. Orians explores the role of evolution in human responses to the environment, beginning with why we have emotions and ending with evolutionary approaches to aesthetics. Orians reveals how our emotional lives today are shaped by decisions our ancestors made centuries ago on African savannas as they selected places to live, sought food and safety, and socialized in small hunter-gatherer groups. During this time our likes and dislikes became wired in our brains, as the appropriate responses to the environment meant the difference between survival or death. His rich analysis explains why we mimic the tropical savannas of our ancestors in our parks and gardens, why we are simultaneously attracted to danger and approach it cautiously, and how paying close attention to nature’s sounds has resulted in us being an unusually musical species. We also learn why we have developed discriminating palates for wine, and why we have strong reactions to some odors, and why we enjoy classifying almost everything.

By applying biological perspectives ranging from Darwin to current neuroscience to analyses of our aesthetic preferences for landscapes, sounds, smells, plants, and animals, Snakes, Sunrises, and Shakespeare transforms how we view our experience of the natural world and how we relate to each other.

Intended for scholars, citizen scientists, and amateur ornithologists, alike, Snowbird synthesizes decades of research from the diverse and talented researchers who study the Junco genus. Though contributors approach their subject from a variety of perspectives, they share a common goal: elucidating the organismal and evolutionary processes by which animals adapt and diversify in response to environmental change. Placing special emphasis on the important role that underlying physiological, hormonal, and behavioral mechanisms play in these processes, Snowbird not only provides a definitive exploration of the junco’s evolutionary history and behavioral and physiological diversity but also underscores the junco’s continued importance as a model organism in a time of rapid global climate change. By merging often disparate biological fields, Snowbird offers biologists across disciplines an integrative framework for further research into adaptation, population divergence, and the formation of new species.

In this book, the biologist Raghavendra Gadagkar focuses on the single species he has worked on throughout his career. Found throughout southern India, Ropalidia marginata is a primitively eusocial wasp--a species in which queens and workers do not differ morphologically and even the latter retain the ability to reproduce. New colonies may be founded by a single fertile female or by several, which then share reproductive and worker duties.

R. marginata has provided Gadagkar with a unique opportunity to study the evolution of eusociality; its long-lived dynasties can continue almost indefinitely, as old or weakened queens are replaced by young and healthy ones and new colonies are founded throughout the year. Understanding such primitively eusocial species is crucial, Gadagkar argues, if we are to understand the evolution of the greater degrees of sociality found in other wasp species and in ants, termites, and bees. His years of study have led him to believe that ecological, physiological, and demographic factors can be more important than genetic relatedness in the selection for or against social traits.

Dean E. Arnold made ten visits to Ticul, Yucatan, Mexico, witnessing the changes in transportation infrastructure, the use of piped water, and the development of tourist resorts. Even in this context of social change and changes in the demand for pottery, most of the potters in 1997 came from the families that had made pottery in 1965. This book traces changes and continuities in that population of potters, in the demand and distribution of pottery, and in the procurement of clay and temper, paste composition, forming, and firing.

In this volume, Arnold bridges the gap between archaeology and ethnography, using his analysis of contemporary ceramic production and distribution to generate new theoretical explanations for archaeologists working with pottery from antiquity. When the descriptions and explanations of Arnold’s findings in Ticul are placed in the context of the literature on craft specialization, a number of insights can be applied to the archaeological record that confirm, contradict, and nuance generalizations concerning the evolution of ceramic specialization. This book will be of special interest to anthropologists, archaeologists, and ethnographers.

Nearly four decades ago Richard Dawkins published The Selfish Gene, famously reducing humans to “survival machines” whose sole purpose was to preserve “the selfish molecules known as genes.” How these selfish genes work together to construct the organism, however, remained a mystery. Standing atop a wealth of new research, The Society of Genes now provides a vision of how genes cooperate and compete in the struggle for life.

Pioneers in the nascent field of systems biology, Itai Yanai and Martin Lercher present a compelling new framework to understand how the human genome evolved and why understanding the interactions among our genes shifts the basic paradigm of modern biology. Contrary to what Dawkins’s popular metaphor seems to imply, the genome is not made of individual genes that focus solely on their own survival. Instead, our genomes comprise a society of genes which, like human societies, is composed of members that form alliances and rivalries.

In language accessible to lay readers, The Society of Genes uncovers genetic strategies of cooperation and competition at biological scales ranging from individual cells to entire species. It captures the way the genome works in cancer cells and Neanderthals, in sexual reproduction and the origin of life, always underscoring one critical point: that only by putting the interactions among genes at center stage can we appreciate the logic of life.

When this classic work was first published in 1975, it created a new discipline and started a tumultuous round in the age-old nature versus nurture debate. Although voted by officers and fellows of the international Animal Behavior Society the most important book on animal behavior of all time, Sociobiology is probably more widely known as the object of bitter attacks by social scientists and other scholars who opposed its claim that human social behavior, indeed human nature, has a biological foundation. The controversy surrounding the publication of the book reverberates to the present day.

In the introduction to this Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Edition, Edward O. Wilson shows how research in human genetics and neuroscience has strengthened the case for a biological understanding of human nature. Human sociobiology, now often called evolutionary psychology, has in the last quarter of a century emerged as its own field of study, drawing on theory and data from both biology and the social sciences.

For its still fresh and beautifully illustrated descriptions of animal societies, and its importance as a crucial step forward in the understanding of human beings, this anniversary edition of Sociobiology: The New Synthesis will be welcomed by a new generation of students and scholars in all branches of learning.

In Sonoran Desert Journeys ecologist Theodore H. Fleming discusses two remarkable journeys. First, Fleming offers a brief history of our intellectual and technical journey over the past three centuries to understand the evolution of life on Earth. Next, he applies those techniques on a journey of discovery about the evolution and natural history of some of the Sonoran Desert’s most iconic animals and plants. Fleming details the daily lives of a variety of reptiles, birds, mammals, and plants, describing their basic natural and evolutionary histories and addressing intriguing issues associated with their lifestyles and how they cope with a changing climate. Finally, Fleming discusses the complexity of Sonoran Desert conservation.

This book explores the evolution and natural history of iconic animals and plants of the northern Sonoran Desert through the eyes of a curious naturalist and provides a model of how we can coexist with the unique species that call this area home.

Are humans too good at adapting to the earth’s natural environment? Every day, there is a net gain of more than 200,000 people on the planet—that’s 146 a minute. Has our explosive population growth led to the mass extinction of countless species in the earth’s plant and animal communities?

Jeffrey K. McKee contends yes. The more people there are, the more we push aside wild plants and animals. In Sparing Nature, he explores the cause-and-effect relationship between these two trends, demonstrating that nature is too sparing to accommodate both a richly diverse living world and a rapidly expanding number of people. The author probes the past to find that humans and their ancestors have had negative impacts on species biodiversity for nearly two million years, and that extinction rates have accelerated since the origins of agriculture. Today entire ecosystems are in peril due to the relentless growth of the human population. McKee gives a guided tour of the interconnections within the living world to reveal the meaning and value of biodiversity, making the maze of technical research and scientific debates accessible to the general reader. Because it is clear that conservation cannot be left to the whims of changing human priorities, McKee takes the unabashedly neo-Malthusian position that the most effective measure to save earth’s biodiversity is to slow the growth of human populations. By conscientiously becoming more responsible about our reproductive habits and our impact on other living beings, we can ensure that nature’s services will make our lives not only supportable, but also sustainable for this century and beyond.

How, asks James E. Strick, could spontaneous generation--the idea that living things can suddenly arise from nonliving materials--come to take root for a time (even a brief one) in so thoroughly unsuitable a field as British natural theology? No less an authority than Aristotle claimed that cases of spontaneous generation were to be observed in nature, and the idea held sway for centuries. Beginning around the time of the Scientific Revolution, however, the doctrine was increasingly challenged; attempts to prove or disprove it led to important breakthroughs in experimental design and laboratory techniques, most notably sterilization methods, that became the cornerstones of modern microbiology and sped the ascendancy of the germ theory of disease.

The Victorian debates, Strick shows, were entwined with the public controversy over Darwin's theory of evolution. While other histories of the debates between 1860 and 1880 have focused largely on the experiments of John Tyndall, Henry Charlton Bastian, and others, Sparks of Life emphasizes previously understudied changes in the theories that underlay the debates. Strick argues that the disputes cannot be understood without full knowledge of the factional infighting among Darwinians themselves, as they struggled to create a socially and scientifically viable form of "Darwinian" science. He shows that even the terms of the debate, such as "biogenesis," usually but incorrectly attributed to Huxley, were intensely contested.

After outlining views of the Modern Synthesis of evolutionary disciplines and detailing the development within paleobiology of quantitative methods for documenting and analyzing variation within fossil assemblages, contributors explore the challenges of recognizing and defining species from fossil specimens—and offer potential solutions. Addressing both the tempo and mode of speciation over time, they show how with careful interpretation and a clear species concept, fossil species may be sufficiently robust for meaningful paleobiological analyses. Indeed, they demonstrate that the species concept, if more refined, could unearth a wealth of information about the interplay between species origins and extinctions, between local and global climate change, and greatly deepen our understanding of the evolution of life.

As Eberhard reveals, the extraordinary diversity of webs includes ingenious solutions to gain access to prey in esoteric habitats, from blazing hot and shifting sand dunes (to capture ants) to the surfaces of tropical lakes (to capture water striders). Some webs are nets that are cast onto prey, while others form baskets into which the spider flicks prey. Some aerial webs are tramways used by spiders searching for chemical cues from their prey below, while others feature landing sites for flying insects and spiders where the spider then stalks its prey. In some webs, long trip lines are delicately sustained just above the ground by tiny rigid silk poles.

Stemming from the author’s more than five decades observing spider webs, this book will be the definitive reference for years to come.

Charles Darwin struggled to explain how forty thousand bees working in the dark, seemingly by instinct alone, could organize themselves to construct something as perfect as a honey comb. How do bees accomplish such incredible tasks? Synthesizing the findings of decades of experiments, The Spirit of the Hive presents a comprehensive picture of the genetic and physiological mechanisms underlying the division of labor in honey bee colonies and explains how bees’ complex social behavior has evolved over millions of years.

Robert Page, one of the foremost honey bee geneticists in the world, sheds light on how the coordinated activity of hives arises naturally when worker bees respond to stimuli in their environment. The actions they take in turn alter the environment and so change the stimuli for their nestmates. For example, a bee detecting ample stores of pollen in the hive is inhibited from foraging for more, whereas detecting the presence of hungry young larvae will stimulate pollen gathering. Division of labor, Page shows, is an inevitable product of group living, because individual bees vary genetically and physiologically in their sensitivities to stimuli and have different probabilities of encountering and responding to them.

A fascinating window into self-organizing regulatory networks of honey bees, The Spirit of the Hive applies genomics, evolution, and behavior to elucidate the details of social structure and advance our understanding of complex adaptive systems in nature.

In this book, Eric Sandweiss scrutinizes the everyday landscape -- streets, houses, neighborhoods, and public buildings -- as it evolved in a classic American city. Bringing to life the spaces that most of us pass without noticing, he reveals how the processes of dividing, trading, improving, and dwelling upon land are acts that reflect and shape social relations. From its origins as a French colonial settlement in the eighteenth century to the present day, St. Louis offers a story not just about how our past is diagrammed in brick and asphalt, but also about the American city's continuing viability as a place where the balance of individual rights and collective responsibilities can be debated, demonstrated and adjusted for generations to come.

"This collection amounts to a retrospective exhibition of a working life. . . . Bateson has come to this position during a career that carried him not only into anthropology, for which he was first trained, but into psychiatry, genetics, and communication theory. . . . He . . . examines the nature of the mind, seeing it not as a nebulous something, somehow lodged somewhere in the body of each man, but as a network of interactions relating the individual with his society and his species and with the universe at large."—D. W. Harding, New York Review of Books

"[Bateson's] view of the world, of science, of culture, and of man is vast and challenging. His efforts at synthesis are tantalizingly and cryptically suggestive. . . .This is a book we should all read and ponder."—Roger Keesing, American Anthropologist

As this book reveals, a new understanding of the evolution of pathogen-host systems, called the Stockholm Paradigm, explains what is happening. The planet is a minefield of pathogens with preexisting capacities to infect susceptible but unexposed hosts, needing only the opportunity for contact. Climate change has always been the major catalyst for such new opportunities, because it disrupts local ecosystem structure and allows pathogens and hosts to move. Once pathogens expand to new hosts, novel variants may emerge, each with new infection capacities. Mathematical models and real-world examples uniformly support these ideas. Emerging disease is thus one of the greatest climate change–related threats confronting humanity.

Even without deadly global catastrophes on the scale of the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic, emerging diseases cost humanity more than a trillion dollars per year in treatment and lost productivity. But while time is short, the danger is great, and we are largely unprepared, the Stockholm Paradigm offers hope for managing the crisis. By using the DAMA (document, assess, monitor, act) protocol, we can “anticipate to mitigate” emerging disease, buying time and saving money while we search for more effective ways to cope with this challenge.

Dating as far back as 2.5-2.7 million years ago, stone tools were used in cutting up animals, woodworking, and preparing vegetable matter. Today, lithic remains give archaeologists insight into the forethought, planning, and enhanced working memory of our early ancestors. Contributors focus on multiple ways in which archaeologists can investigate the relationship between tools and the evolving human mind-including joint attention, pattern recognition, memory usage, and the emergence of language.

Offering a wide range of approaches and diversity of place and time, the chapters address issues such as skill, social learning, technique, language, and cognition based on lithic technology. Stone Tools and the Evolution of Human Cognition will be of interest to Paleolithic archaeologists and paleoanthropologists interested in stone tool technology and cognitive evolution.

Southern Presbyterian theologians enjoyed a prominent position in antebellum southern culture. Respected for both their erudition and elite constituency, these theologians identified the southern society as representing a divine, Biblically ordained order. Beginning in the 1840s, however, this facile identification became more difficult to maintain, colliding first with antislavery polemics, then with Confederate defeat and reconstruction, and later with women’s rights, philosophical empiricism, literary criticisms of the Bible, and that most salient symbol of modernity, natural science.

As Monte Harrell Hampton shows in Storm of Words, modern science seemed most explicitly to express the rationalistic spirit of the age and threaten the Protestant conviction that science was the faithful “handmaid” of theology. Southern Presbyterians disposed of some of these threats with ease. Contemporary geology, however, posed thornier problems. Ambivalence over how to respond to geology led to the establishment in 1859 of the Perkins Professorship of Natural Science in Connexion with Revealed Religion at the seminary in Columbia, South Carolina. Installing scientist-theologian James Woodrow in this position, southern Presbyterians expected him to defend their positions.

Within twenty-five years, however, their anointed expert held that evolution did not contradict scripture. Indeed, he declared that it was in fact God’s method of creating. The resulting debate was the first extended evolution controversy in American history. It drove a wedge between those tolerant of new exegetical and scientific developments and the majority who opposed such openness. Hampton argues that Woodrow believed he was shoring up the alliance between science and scripture—that a circumscribed form of evolution did no violence to scriptural infallibility. The traditionalists’ view, however, remained interwoven with their identity as defenders of the Lost Cause and guardians of southern culture.

The ensuing debate triggered Woodrow’s dismissal. It also capped a modernity crisis experienced by an influential group of southern intellectuals who were grappling with the nature of knowledge, both scientific and religious, and its relationship to culture—a culture attempting to define itself in the shadow of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Decisions about war have always been made by humans, but now intelligent machines are on the cusp of changing things – with dramatic consequences for international affairs. This book explores the evolutionary origins of human strategy, and makes a provocative argument that Artificial Intelligence will radically transform the nature of war by changing the psychological basis of decision-making about violence.

Strategy, Evolution, and War is a cautionary preview of how Artificial Intelligence (AI) will revolutionize strategy more than any development in the last three thousand years of military history. Kenneth Payne describes strategy as an evolved package of conscious and unconscious behaviors with roots in our primate ancestry. Our minds were shaped by the need to think about warfare—a constant threat for early humans. As a result, we developed a sophisticated and strategic intelligence.

The implications of AI are profound because they depart radically from the biological basis of human intelligence. Rather than being just another tool of war, AI will dramatically speed up decision making and use very different cognitive processes, including when deciding to launch an attack, or escalate violence. AI will change the essence of strategy, the organization of armed forces, and the international order.

This book is a fascinating examination of the psychology of strategy-making from prehistoric times, through the ancient world, and into the modern age.

The contributors chart the history of U.S. trade policy since World War II, analyze industry-specific trade barriers, and discuss the effects of tariff preferences and export-promoting policies such as export credits and domestic international sales corporations (DISCs). The final section of essays examines the worldwide impact of import policies, pointing out subtleties in industry-specific policies and providing insight into the levels of protection in developing countries. The contributors blend state-of-the-art economics with language that is accessible to the business community, economists, and policymakers. Commentaries accompany each paper.

The world's most revered and eloquent interpreter of evolutionary ideas offers here a work of explanatory force unprecedented in our time--a landmark publication, both for its historical sweep and for its scientific vision.

With characteristic attention to detail, Stephen Jay Gould first describes the content and discusses the history and origins of the three core commitments of classical Darwinism: that natural selection works on organisms, not genes or species; that it is almost exclusively the mechanism of adaptive evolutionary change; and that these changes are incremental, not drastic. Next, he examines the three critiques that currently challenge this classic Darwinian edifice: that selection operates on multiple levels, from the gene to the group; that evolution proceeds by a variety of mechanisms, not just natural selection; and that causes operating at broader scales, including catastrophes, have figured prominently in the course of evolution.

Then, in a stunning tour de force that will likely stimulate discussion and debate for decades, Gould proposes his own system for integrating these classical commitments and contemporary critiques into a new structure of evolutionary thought.

In 2001 the Library of Congress named Stephen Jay Gould one of America's eighty-three Living Legends--people who embody the "quintessentially American ideal of individual creativity, conviction, dedication, and exuberance." Each of these qualities finds full expression in this peerless work, the likes of which the scientific world has not seen--and may not see again--for well over a century.

A landmark work of nineteenth-century developmental and evolutionary biology that takes the Darwinian struggle for existence into the organism itself.

Though he is remembered primarily as a pioneer of experimental embryology, Wilhelm Roux was also a groundbreaking evolutionary theorist. Years before his research on chicken and frog embryos cemented his legacy as an experimentalist, Roux endorsed the radical idea that a “struggle for existence” within organisms—between organs, tissues, cells, and even subcellular components—drives individual development.

Convinced that external competition between individuals is inadequate to explain the exquisite functionality of bodily parts, Roux aimed to uncover the mechanistic principles underlying self-organization. The Struggle of Parts was his attempt to provide such a theory. Combining elements of Darwinian selection and Lamarckian inheritance of acquired characteristics, the work advanced a materialist explanation of how “purposiveness” within the organism arises as the body’s components compete for space and nourishment. The result, according to Charles Darwin, was “the most important book on evolution which has appeared for some time.”

Translated into English for the first time by evolutionary biologist David Haig and Richard Bondi, The Struggle of Parts represents an important forgotten chapter in the history of developmental and evolutionary theory.

Being human while trying to scientifically study human nature confronts us with our most vexing problem. Efforts to explicate the human mind are thwarted by our cultural biases and entrenched infirmities; our first-person experiences as practical agents convince us that we have capacities beyond the reach of scientific explanation. What we need to move forward in our understanding of human agency, Paul Sheldon Davies argues, is a reform in the way we study ourselves and a long overdue break with traditional humanist thinking.

Davies locates a model for change in the rhetorical strategies employed by Charles Darwin in On the Origin of Species. Darwin worked hard to anticipate and diminish the anxieties and biases that his radically historical view of life was bound to provoke. Likewise, Davies draws from the history of science and contemporary psychology and neuroscience to build a framework for the study of human agency that identifies and diminishes outdated and limiting biases. The result is a heady, philosophically wide-ranging argument in favor of recognizing that humans are, like everything else, subjects of the natural world—an acknowledgement that may free us to see the world the way it actually is.

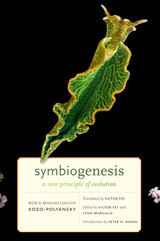

More than eighty years ago, before we knew much about the structure of cells, Russian botanist Boris Kozo-Polyansky brilliantly outlined the concept of symbiogenesis, the symbiotic origin of cells with nuclei. It was a half-century later, only when experimental approaches that Kozo-Polyansky lacked were applied to his hypotheses, that scientists began to accept his view that symbiogenesis could be united with Darwin's concept of natural selection to explain the evolution of life. After decades of neglect, ridicule, and intellectual abuse, Kozo-Polyansky's ideas are now endorsed by virtually all biologists.

Kozo-Polyansky's seminal work is presented here for the first time in an outstanding annotated translation, updated with commentaries, references, and modern micrographs of symbiotic phenomena.

This book addresses a simple question: Are animals designed economically? The pronghorn can run at speeds of up to 60 kilometers an hour and can maintain this speed for nearly a full hour. Clearly, the form of this elegant animal is beautifully matched to the function it needs to perform.

This is symmorphosis. The theory of symmorphosis predicts that the size of the parts in a system must be matched to the overall functional demand. Moreover, it predicts that animals must provide their complex systems with a functional capacity that can cope with the highest expected functional demands, possibly including some safety margin to prevent the system from failing when it is overloaded. In Symmorphosis, Ewald Weibel tests these predictions by working out the quantitative relations between form and function.

Physiologists will value this book because Weibel shows them that morphological information can be as quantitative as physiological data. Anatomists will value the book for its demonstration that advanced integrative physiology crucially depends on adequate but rigorously quantitative and testable information on structural design. Finally, anyone interested in the origins of the diverse forms of animals will be fascinated by Weibel's demonstrations that show how animals as different as shrews, pronghorns, dogs, goats--even humans--all develop from essentially the same blueprint by variation of design. This is a hidden beauty of the animal kingdom, which can be uncovered by a rigorous investigation of the quantitative relations of form and function.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press