Whether exploring Bresson’s efforts to reassess the limits of human reason and will, Dostoevsky’s subversions of Christian conventions, Tolstoy’s incompatible beliefs about death, or Kafka’s focus on creatures neither human nor animal, Cameron illuminates how the repeated juxtaposition of disparate, even antithetical, phenomena carves out new approaches to defining the essence of being, one where the very nature of fixed categories is brought into question. An innovative look at a classic French auteur and three giants of European literature, The Bond of the Furthest Apart will interest scholars of literature, film, ethics, aesthetics, and anyone drawn to an experimental venture in critical thought.

In fresh, often surprising readings of Dostoevsky's individual works, Leatherbarrow shows how such a "language" articulates a series of concerns linked to views expressed elsewhere—in Dostoevsky's journalism and letters—on the question of Russia's relationship to Western Europe. His study also explores the narrative and generic implications of the way Dostoevsky inscribes the demonic in his fictional works—implications that point to a new understanding of familiar concepts in the work of this Russian master. Highly original, deftly argued and written, Leatherbarrow's work offers Dostoevsky specialists and general readers alike an opportunity to rediscover and reassess the rich complexities of some of the world's greatest literature.

Some of the topics Fusso considers are Dostoevsky's search for an appropriate artistic language for sexuality, a young narrator's experimentation with homoerotic desire and unconventional narrative in A Raw Youth; and Dostoevsky's approach to a young man's sexual development in A Raw Youth and The Brothers Karamazov. She also explores his complex treatment of a child's secret sexuality in his account of the Kroneberg child abuse case in A Writer's Diary; and his conception of the ideal family, a type of family that appears in his works mainly by negative example. Focusing mainly on sexual practices considered "deviant" in Dostoevsky's time--both because these are the practices that his young characters confront and because they offer the most intriguing interpretive problems--Fusso decodes the author's texts and their social contexts. In doing so, she highlights one thread in the intricate thematic weave of Dostoevsky's novels and newly illuminates his artistic process.

The Idiot is perhaps the most difficult and surely most enigmatic of Dostoevsky’s novels. In it the novelist developed a narrator-chronicler who uses an intricate web of alternately truthful and deceptive words to create a narrative of baffling intricacy. The reader is confronted with moral and ethical problems and is forced to make his or her own decisions about the import of what has occurred.

Robin Miller analyzes the varied narrative modes and voices, as well as the inserted narratives, and examines the effects of all these on the reader. She has derived helpful insights from current writing about the phenomenology of reading by such critics as Wayne Booth, Wolfgang Iser, and Stanley Fish. She draws extensively on Dostoevsky’s letters, notebooks, and journalistic writings in describing his ideas about his readers and about the craft of fiction. These writings also provide clues to the importance of Rousseau’s Confessions and the Gothic novels for the development of Dostoevsky’s narrative techniques. The notebooks, moreover, are an indispensable source of information concerning the genesis of The Idiot and the radical changes it underwent in the course of its composition.

Although the book is primarily a close reading of The Idiot, it throws light on the later novels, The Possessed and The Brothers Karamazov, in which Dostoevsky again makes use of a fictional narrator.

While Dostoevsky’s relation to religion is well-trod ground, there exists no comprehensive study of Dostoevsky and Catholicism. Elizabeth Blake’s ambitious and learned Dostoevsky and the Catholic Underground fills this glaring omission in the scholarship. Previous commentators have traced a wide-ranging hostility in Dostoevsky’s understanding of Catholicism to his Slavophilism. Blake depicts a far more nuanced picture. Her close reading demonstrates that he is repelled and fascinated by Catholicism in all its medieval, Reformation, and modern manifestations. Dostoevsky saw in Catholicism not just an inspirational source for the Grand Inquisitor but a political force, an ideological wellspring, a unique mode of intellectual inquiry, and a source of cultural production. Blake’s insightful textual analysis is accompanied by an equally penetrating analysis of nineteenth-century European revolutionary history, from Paris to Siberia, that undoubtedly influenced the evolution of Dostoevsky’s thought.

Dostoevsky and the Riddle of the Self charts a unifying path through Dostoevsky's artistic journey to solve the “mystery” of the human being. Starting from the unusual forms of intimacy shown by characters seeking to lose themselves within larger collective selves, Yuri Corrigan approaches the fictional works as a continuous experimental canvas on which Dostoevsky explored the problem of selfhood through recurring symbolic and narrative paradigms. Presenting new readings of such works as The Idiot, Demons, and The Brothers Karamazov, Corrigan tells the story of Dostoevsky’s career-long journey to overcome the pathology of collectivism by discovering a passage into the wounded, embattled, forbidding, revelatory landscape of the psyche.

Corrigan’s argument offers a fundamental shift in theories about Dostoevsky's work and will be of great interest to scholars of Russian literature, as well as to readers interested in the prehistory of psychoanalysis and trauma studies and in theories of selfhood and their cultural sources.

In the essays brought together in this volume Shestov presents a profound and original analysis of the thought of three of the most brilliant literary figures of nineteenth-century Europe—Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Nietzsche—all of whom had a decisive influence on the development of his own philosophy.

According to Shestov, the greatness of these writers consists in their deep probing into the question of the meaning of life and the problems of human suffering, evil, and death. That all three of them at times abandoned their probing and lapsed into the banality of preaching does not diminish their stature but shows only that there are limits to man’s capacity for looking unflichingly at reality.

Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Nietzsche are united, in Shestov’s view, by their common insight into the essential tragedy of human life—a tragedy which no increase in scientific knowledge and no degree of political and social reform can significantly mitigate but which can ultimately be redeemed only by faith in the omnipotent God proclaimed by the Bible.

In all three of his subjects Shestov sees a rebellion against the tyranny of idealist systems of philosophy, as well as a recognition that the supposedly universal and necessary laws discovered by science and the moral principles for which autonomous ethics claims eternal validity do not liberate man but rather crush and destroy him. This rebellion and this recognition are often suppressed by Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, and Nietzsche, byt they break forth again and again with overwhelming power.

In this provocative discussion of the novels and stories of the two celebrated Russian writers and of the essays and aphorisms of the solitary German philosopher whose genius was finally extinguished by insanity, Shestov finds ideas and insights that other critics have overlooked or the important of which they have not adequately understood. The value of his achievement has been widely recognized. Prince Mirsky, for example, does not hesitate to say in his authorative history of Russian literature that, as far as Dostoevsky is concerned, Shestov is undoubtedly his greatest commentator.

The reader will find in these remarkable studies of the men who exercised the strongest intellectual influence on the young Shestov the beginnings of the Russian philosopher’s own lifelong polemic against idealism, scientism, and conventional morality, as well as the first gropings of the quest for faith in the Biblical God that was to become the leitmotif of all his thinking and writing in the last decades of his life.

In Dostoevsky’s Dialectics and the Problem of Sin, Ksana Blank borrows from ancient Greek, Chinese, and Christian dialectical traditions to formulate a dynamic image of Dostoevsky’s dialectics—distinct from Hegelian dialectics—as a philosophy of “compatible contradictions.” Expanding on the classical triad of Goodness, Beauty, and Truth, Blank guides us through Dostoevsky’s most difficult paradoxes: goodness that begets evil, beautiful personalities that bring about grief, and criminality that brings about salvation.

Dostoevsky’s philosophy of contradictions, this book demonstrates, contributes to the development of antinomian thought in the writings of early twentieth-century Russian religious thinkers and to the development of Bakhtin’s dialogism. Dostoevsky’s Dialectics and the Problem of Sin marks an important and original intervention into the enduring debate over Dostoevsky’s spiritual philosophy.

In three chapters, French takes up in turn the narrator and narrative points of view, the author’s use of inserted narratives, and three modes of interaction French calls Monologue, Dialogue, and Dialogical Living.

Confronting Bakhtin’s formative reading of Dostoevsky to recover the ways the novelist stokes conflict and engages readers—and to explore the reasons behind his adversarial approach

Like so many other elements of his work, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s deliberate deployment of provocation was both prescient and precocious. In this book, Lynn Ellen Patyk singles out these forms of incitement as a communicative strategy that drives his paradoxical art. Challenging, revising, and expanding on Mikhail Bakhtin’s foundational analysis in Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics, Patyk demonstrates that provocation is the moving mover of Dostoevsky’s poetics of conflict, and she identifies the literary devices he uses to propel plot conflict and capture our attention. Yet the full scope of Dostoevsky’s provocative authorial activity can only be grasped alongside an understanding of his key themes, which both probed and exploited the most divisive conflicts of his era. The ultimate stakes of such friction are, for him, nothing less than moral responsibility and the truth of identity.

Sober and strikingly original, compassionate but not uncritical, Dostoevsky’s Provocateurs exposes the charged current in the wiring of our modern selves. In an economy of attention and its spoils, provocation is an inexhaustibly renewable and often toxic resource.

Porter shows how, for Pushkin, Gogol, Dostoevsky, and Faddei Bulgarin, ambition became a staging ground for experiments with transnational literary exchange. In its encounters with the celebrated Russian cultural value of hospitality and the age-old vice of miserliness, ambition appears both timely and anachronistic, suspiciously foreign and disturbingly Russian—it challenges readers to question the equivalence of local and imported words, feelings, and forms.

Economies of Feeling examines founding texts of nineteenth-century Russian prose alongside nonliterary materials from which they drew energy—from French clinical diagnoses of “ambitious monomania” to the various types of currency that proliferated under Nicholas I. It thus contributes fresh and fascinating insights into Russian characters’ impulses to attain rank and to squander, counterfeit, and hoard. Porter’s interdisciplinary approach will appeal to scholars of comparative as well as Russian literature.

In his introduction, Terras outlines the genesis, main ideas, and structural peculiarities of the novel as well as Dostoevsky’s political, philosophical, and aesthetic stance. The detailed commentary takes the reader through the novel, clarifying aspects of Russian life, the novel’s sociopolitical background, and a number of polemic issues. Terras identifies and explains hundreds of literary and biblical quotations and allusions. He discusses symbols, recurrent images, and structural stylistic patterns, including those lost in English translation.

Arranged chronologically, the essays are grouped in three sections corresponding to the major periods of Merleau-Ponty’s work: First, the years prior to his appointment to the Sorbonne in 1949, the early, existentialist period during which he wrote important works on the phenomenology of perception and the primacy of perception; second, the years of his work as professor of child psychology and pedagogy at the Sorbonne, a period especially concerned with language; and finally, his years as chair of modern philosophy at the Collège de France, a time devoted to the articulation of a new ontology and philosophy of nature. The editors, who provide an interpretive introduction, also include previously unpublished working notes found in Merleau-Ponty’s papers after his death. Translations of all selections have been updated and several appear here in English for the first time.

By contextualizing Merleau-Ponty’s writings on the philosophy of art and politics within the overall development of his thought, this volume allows readers to see both the breadth of his contribution to twentieth-century philosophy and the convergence of the various strands of his reflection.

Through new readings of War and Peace, Anna Karenina, The Brothers Karamazov, and other novels, Kitzinger traces a productive tension between mimetic characterization and the author’s ambition to transform the reader. She shows how Tolstoy and Dostoevsky create lifelike characters and why the dream of carrying the illusion of “life” beyond the novel consistently fails. Mimetic Lives challenges the contemporary truism that novels educate us by providing enduring models for the perspectives of others, with whom we can then better empathize. Seen close, the realist novel’s power to create a world of compelling fictional persons underscores its resources as a form for thought and its limits as a direct source of spiritual, social, or political change.

Drawing on scholarship in Russian literary studies as well as the theory of the novel, Kitzinger’s lucid work of criticism will intrigue and challenge scholars working in both fields.

Edited by the nation's most respected senior Dostoevsky scholar, this collection brings together original work by notable writers of varying backgrounds and interests. While drawing on Dostoevsky's other fiction, journalism, and correspondence, the writing of his contemporaries, the state of Russian culture to illuminate the unfolding novel--these essays also make use of new fields of scholarship, such as cognitive psychology, as well as recent theoretical approaches and critical insights. The authors propose readings remarkable for their attentiveness to detail, relatively peripheral characters, and heretofore overlooked incidents, passages, or fragments of dialogue. Some contributors suggest readings so new that they are subvert our usual modes of approaching this novel; all reflect the immediacy of adventuresome, informed encounters with Dostoevsky's final novel. Treating The Brothers Karamazov in terms of a broad range of genres (poetry, narrative, parody, confession, detective fiction) and discourses (medical, scientific, sexual, judicial, philosophical, and theological), these essays embody on a critical and analytic level a search for coherence, meaning, and harmony that continues to animate Dostoevsky's novel in our day.

In thoughtful readings of Demons, The Adolescent, A Writer’s Diary, and The Brothers Karamazov, Holland delineates Dostoevsky’s struggle to adapt a genre to the reality of the present, with all its upheavals, while maintaining a utopian vision of Russia’s future mission.

Reader as Accomplice: Narrative Ethics in Dostoevsky and Nabokov argues that Fyodor Dostoevsky and Vladimir Nabokov seek to affect the moral imagination of their readers by linking morally laden plots to the ethical questions raised by narrative fiction at the formal level. By doing so, these two authors ask us to consider and respond to the ethical demands that narrative acts of representation and interpretation place on authors and readers.

Using the lens of narrative ethics, Alexander Spektor brings to light the important, previously unexplored correspondences between Dostoevsky and Nabokov. Ultimately, he argues for a productive comparison of how each writer investigates the ethical costs of narrating oneself and others. He also explores the power dynamics between author, character, narrator, and reader. In his readings of such texts as “The Meek One” and The Idiot by Dostoevsky and Bend Sinister and Despair by Nabokov, Spektor demonstrates that these authors incite the reader’s sense of ethics by exposing the risks but also the possibilities of narrative fiction.

“A substantial contribution both to Dostoevsky scholarship and to scholarship on the novel. . . . The first book in quite a while to address itself to all of Dostoevsky’s opus, certainly a bold move that only someone of Terras’s stature could pull off.”—Gary Rosenshield, University of Madison–Wisconsin

Admirers have praised Fedor Dostoevsky as the Russian Shakespeare, while his critics have slighted his novels as merely cheap amusements. In this stimulating critical introduction to Dostoevsky’s fiction, literary scholar Victor Terras asks readers to draw their own conclusions about the nineteenth-century Russian writer. Discussing psychological, political, mythical, and philosophical approaches, Terras deftly guides readers through the range of diverse and even contradictory interpretations of Dostoevsky's rich novels.

Moving through the novelist's career, Terras presents a general analysis of the novel at issue, each chapter focusing on a particular aspect of Dostoevsky's art. He probes the form and style of Crime and Punishment, and explores the ambiguity of The Brothers Karamazov. Terras emphasizes the "markedness," of Dostoevsky's novels, their wealth of literary devices such as irony, literary allusions, scenic effects, puns, and witticisms.

Terras conveys the vital contradictions and ambiguities of the novels. In this informative, engaging literary study, Terras brings Dostoevsky and his art to life.

In a fascinating analysis of critical themes in Feodor Dostoevsky’s work, René Girard explores the implications of the Russian author’s “underground,” a site of isolation, alienation, and resentment. Brilliantly translated, this book is a testament to Girard’s remarkable engagement with Dostoevsky’s work, through which he discusses numerous aspects of the human condition, including desire, which Girard argues is “triangular” or “mimetic”—copied from models or mediators whose objects of desire become our own. Girard’s interdisciplinary approach allows him to shed new light on religion, spirituality, and redemption in Dostoevsky’s writing, culminating in a revelatory discussion of the author’s spiritual understanding and personal integration. Resurrection is an essential and thought-provoking companion to Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground.

Russia’s Capitalist Realism examines how the literary tradition that produced the great works of Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Anton Chekhov responded to the dangers and possibilities posed by Russia’s industrial revolution. During Russia’s first tumultuous transition to capitalism, social problems became issues of literary form for writers trying to make sense of economic change. The new environments created by industry, such as giant factories and mills, demanded some kind of response from writers but defied all existing forms of language.

This book recovers the rich and lively public discourse of this volatile historical period, which Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Chekhov transformed into some of the world’s greatest works of literature. Russia’s Capitalist Realism will appeal to readers interested in nineteenth‑century Russian literature and history, the relationship between capitalism and literary form, and theories of the novel.

A literary scholar and investment banker applies economic criticism to canonical novels, dramatically changing the way we read these classics and proposing a new model for how economics can inform literary analysis.

Every writer is a player in the marketplace for literature. Jonathan Paine locates the economics ingrained within the stories themselves, revealing how a text provides a record of its author’s attempt to sell the story to his or her readers.

An unusual literary scholar with a background in finance, Paine mines stories for evidence of the conditions of their production. Through his wholly original reading, Balzac’s The Splendors and Miseries of Courtesans becomes a secret diary of its author’s struggles to cope with the commercializing influence of serial publication in newspapers. The Brothers Karamazov transforms into a story of Dostoevsky’s sequential bets with his readers, present and future, about how to write a novel. Zola’s Money documents the rise of big business and is itself a product of Zola’s own big business, his factory of novels.

Combining close readings with detailed analyses of the nineteenth-century publishing contexts in which prose fiction first became a product, Selling the Story shows how the business of literature affects even literary devices such as genre, plot, and repetition. Paine argues that no book can be properly understood without reference to its point of sale: the author’s knowledge of the market, of reader expectations, and of his or her own efforts to define and achieve literary value.

Anna A. Berman’s book brings to light the significance of sibling relationships in the writings of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky. Relationships in their works have typically been studied through the lens of erotic love in the former, and intergenerational conflict in the latter.

In close readings of their major novels, Berman shows how both writers portray sibling relationships as a stabilizing force that counters the unpredictable, often destructive elements of romantic entanglements and the hierarchical structure of generations. Power and interconnectedness are cast in a new light. Berman persuasively argues that both authors gradually come to consider siblinghood a model of all human relations, discerning a career arc in each that moves from the dynamics within families to a much broader vision of universal brotherhood.

In Surprised by Shame, Deborah A. Martinsen combines shame studies and literary criticism. She begins with a discussion of shame dynamics, including the tendency of those who witness shame to feel shame themselves. Because Dostoevsky identified shame as a fundamental source of lying, Martinsen focuses on scenes when liars are exposed. She argues that by making readers witness such scandal scenes, Dostoevsky surprises them with shame, thereby collapsing the distance between readers and characters and viscerally involving them in his message of human interconnection.

Treating Dostoevsky’s liars as case studies, Surprised by Shame discusses varieties of shame and shamelessness; it also illustrates how Dostoevsky uses lying to indicate and expose subconscious processes. In addition, Martinsen demonstrates how Dostoevsky plucks shame from the realm of character trait and plot motive and embeds it in the narrative dynamics of The Idiot, Demons, and The Brothers Karamazov, thereby plunging readers into fictional experience and ethically transforming them.

By focusing on shame, this book uncovers new perspectives on Dostoevsky as writer and psychologist. By exposing how shame dynamics implicate readers in texts’ ethical actions, it enriches understanding of his tremendous influence on twentieth-century thinkers and writers. Finally, reading Dostoevsky as a prophet of shame-begotten violence reveals his universal relevance in a twenty-first century already scarred by acts of violence.

The defining quality of Russian literature, for most critics, is its ethical seriousness expressed through formal originality. The Trace of Judaism addresses this characteristic through the thought of the Lithuanian-born Franco-Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. Steeped in the Russian classics from an early age, Levinas drew significantly from Dostoevsky in his ethical thought. One can profitably read Russian literature through Levinas, and vice versa.

Turned Inside Out will appeal to readers with interests in the classic novels of Russian literature, in prisons and pedagogy, or in Levinas and phenomenology. At a time when the humanities are struggling to justify the centrality of their mission in today’s colleges and universities, Steven Shankman by example makes an undeniably powerful case for the transformative power of reading great texts.

As Dostoevsky attempts to balance the various ethical and cultural imperatives, he displays ambivalence both about punishment and about mercy. This ambivalence, Schur argues, is further complicated by what Dostoevsky sees as the unfathomable quality of the self, which hinders every attempt to match crimes with punishments. The one certainty he holds is that a proper response to wrongdoing must include a concern for the wrongdoer’s moral improvement.

From Dostoevsky, Percy learned how to captivate his non-Christian readership with fiction saturated by a Christian vision of reality. Not only was his method of imitation in line with this Christian faith but also the aesthetic mode and very content of his narratives centered on his knowledge of Christ. The influence of Dostoevsky on Percy, then, becomes significant as a modern case study for showing the illusion of artistic autonomy and long-held, Romantic assumptions about artistic originality. Ultimately, Wilson suggests, only by studying the good that came before can one translate it in a new voice for the here and now.

In June 1862, Dostoevsky left Petersburg on his first excursion to Western Europe. Ostensibly making the trip to consult Western specialists about his epilepsy, he also wished to see firsthand the source of the Western ideas he believed were corrupting Russia. Over the course of his journey he visited a number of major cities, including Berlin, Paris, London, Florence, Milan, and Vienna. He recorded his impressions in Winter Notes on Summer Impressions, which were first published in the February 1863 issue of Vremya (Time), the periodical of which he was the editor.

Among other themes, Dostoevsky reveals his Pan-Slavism, rejecting European culture as corrupt and exhorting Russians to resist the temptation to emulate or adopt European ways of life.

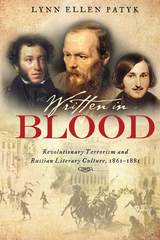

Lynn Ellen Patyk contends that the prototype for the terrorist was the Russian writer, whose seditious word was interpreted as an audacious deed—and a violent assault on autocratic authority. The interplay and interchangeability of word and deed, Patyk argues, laid the semiotic groundwork for the symbolic act of violence at the center of revolutionary terrorism. While demonstrating how literary culture fostered the ethos, pathos, and image of the revolutionary terrorist and terrorism, she spotlights Fyodor Dostoevsky and his "terrorism trilogy"—Crime and Punishment (1866), Demons (1870–73), and The Brothers Karamazov (1878–80)—as novels that uniquely illuminate terrorism's methods and trajectory. Deftly combining riveting historical narrative with penetrating literary analysis of major and minor works, Patyk's groundbreaking book reveals the power of the word to spawn deeds and the power of literature to usher new realities into the world.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2024

The University of Chicago Press