204 start with I start with I

Abducted at the age of eleven, Evelyn Amony spent nearly eleven years inside the Lord’s Resistance Army, becoming a forced wife to Joseph Kony and mother to his children. She takes the reader into the inner circles of LRA commanders and reveals unprecedented personal and domestic details about Joseph Kony. Her account unflinchingly conveys the moral difficulties of choosing survival in a situation fraught with violence, threat, and death.

Amony was freed following her capture by the Ugandan military. Despite the trauma she endured with the LRA, Amony joined a Ugandan peace delegation to the LRA, trying to convince Kony to end the war that had lasted more than two decades. She recounts those experiences, as well as the stigma she and her children faced when she returned home as an adult.

This extraordinary testimony shatters stereotypes of war-affected women, revealing the complex ways that Amony navigated life inside the LRA and her current work as a human rights advocate to make a better life for her children and other women affected by war.

Best books for public & secondary school libraries from university presses, American Library Association

The book presents a critical reexamination of Andrew Topolski, an overlooked luminary of intermedia and postminimalism. In repositioning Topolski’s legacy and vast body of work, Ryan makes compelling findings about the interplay of talent, luck, and community support in the making or breaking of artistic careers. At the same time, the story shares the significant and never-before-seen body of work by Cindy Suffoletto, a talented and inventive artist little shown and never cataloged during her short life. Ultimately, Ryan argues that the time is right for both to take up a privileged place among the great artists of their generation.

A uniquely poetic contribution to the small body of internment memoirs, Suyemoto's account includes information about policies and wartime decisions that are not widely known, and recounts in detail the way in which internees adjusted their notions of selfhood and citizenship, lending insight to the complicated and controversial questions of citizenship, accountability, and resistance of first- and second-generation Japanese Americans.

Suyemoto's poems, many written during internment, are interwoven throughout the text and serve as counterpoints to the contextualizing narrative. Suyemoto's poems, many written during internment, are interwoven throughout the text and serve as counterpoints to the contextualizing narrative. A small collection of poems written in the years following her incarceration further reveal the psychological effects of her experience.

Warwick, the world's leading expert in cybernetics, explains how he has deliberately crossed over a perilous threshold to take the first practical steps toward becoming a cyborg--part human, part machine--using himself as a guinea pig and undergoing surgery to receive technological implants connected to his central nervous system.

Believing that machines with intelligence far beyond that of humans will eventually make the important decisions, Warwick investigates whether we can avoid obsolescence by using technology to improve on our comparatively limited capabilities. Warwick also discusses the implications for human relationships, and his wife's participation in the experiments.

Beyond the autobiography of a scientist who became, in part, a machine, I, Cyborg is also a story of courage, devotion, and endeavor that split apart personal lives. The results of these amazing experiments have far-reaching implications not only for e-medicine, extra-sensory input, increased memory and knowledge, and even telepathy, but for the future of humanity as well.

When Viviana Salguero came to the United States in 1946, she spoke very little English, had never learned to read or write, and had no job skills besides housework or field labor. She worked eighteen-hour days and lived outdoors as often as not. And yet she raised twelve children, shielding them from her abusive husband when she dared, and shared in both the tragedies and accomplishments of her family. Through it all, Viviana never lost her love for Mexico or her gratitude to the United States for what would eventually become a better life. Though her story is unique, Viviana Salguero could be the mother, grandmother, or great-grandmother of immigrants anywhere, struggling with barriers of gender, education, language, and poverty.

In I Don't Cry, But I Remember, Joyce Lackie shares with us an intimate portrait of Viviana's life. Based on hours of recorded conversations, Lackie skillfully translates the interviews into an engaging, revealing narrative that details the migrant experience from a woman's point of view and fills a gap in our history by examining the role of women of color in the American Southwest. The book presents Vivana's life not only as a chronicle of endurance, but as a tale of everyday resistance. What she lacks in social confidence, political strength, and economic stability, she makes up for in dignity, faith, and wisdom.

Like all good oral history, Salguero's accounts and Lackie's analyses contribute to our understanding of the past by exposing the inconsistencies and contradictions in our remembrances. This book will appeal to ethnographers, oral historians, students and scholars of Chicana studies and women's studies, as well as general readers interested in the lives of immigrant women.

A major figure in American blues and folk music, Big Bill Broonzy (1903–1958) left his Arkansas Delta home after World War I, headed north, and became the leading Chicago bluesman of the 1930s. His success came as he fused traditional rural blues with the electrified sound that was beginning to emerge in Chicago. This, however, was just one step in his remarkable journey: Big Bill was constantly reinventing himself, both in reality and in his retellings of it. Bob Riesman’s groundbreaking biography tells the compelling life story of a lost figure from the annals of music history.

I Feel So Good traces Big Bill’s career from his rise as a nationally prominent blues star, including his historic 1938 appearance at Carnegie Hall, to his influential role in the post-World War II folk revival, when he sang about racial injustice alongside Pete Seeger and Studs Terkel. Riesman’s account brings the reader into the jazz clubs and concert halls of Europe, as Big Bill's overseas tours in the 1950s ignited the British blues-rock explosion of the 1960s. Interviews with Eric Clapton, Pete Townshend, and Ray Davies reveal Broonzy’s profound impact on the British rockers who would follow him and change the course of popular music.

Along the way, Riesman details Big Bill’s complicated and poignant personal saga: he was married three times and became a father at the very end of his life to a child half a world away. He also brings to light Big Bill’s final years, when he first lost his voice, then his life, to cancer, just as his international reputation was reaching its peak. Featuring many rarely seen photos, I Feel So Good will be the definitive account of Big Bill Broonzy’s life and music.

Once considered the most stable country in West Africa, Ivory Coast was split by an armed rebellion in 2002 and endured a decade of instability and a violent conflict. Spindel provides an intimate glimpse into this turbulent period by weaving together the daily lives and paths of five neighbors. Their stories reveal Ivorians determined to reunite a divided country through reliance on mutual respect and obligation even while power-hungry politicians pursued xenophobic and anti-immigrant platforms for personal gain. Illuminating democracy as a fragile enterprise that must be continually invented and reinvented, I Give You Half the Road emphasizes the importance of connection, generosity, and forgiveness.

The Best Narrative & Biography Books of 2024, Selected by Porchlight

When a progressive college professor runs for the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in a deeply conservative rural district, he loses. That’s no surprise. But the story of how Ferrence loses and, more importantly, how American political narratives refuse to recognize the existence and value of nonconservative rural Americans offers insight into the political morass of our nation.

In essays focused on showing goats at the county fair, planting native grasses in the front lawn, the political power of poetry, and getting wiped out in an election, Ferrence offers a counter-narrative to stereotypes of monolithic rural American voters and emphasizes the way stories told about rural America are a source for the bitter divide between Red America and Blue America.

“[An] extraordinary book.” —New Republic

Fusing high scholarship with high drama, Anthony Grafton and Joanna Weinberg uncover a secret and extraordinary aspect of a legendary Renaissance scholar’s already celebrated achievement. The French Protestant Isaac Casaubon (1559–1614) is known to us through his pedantic namesake in George Eliot’s Middlemarch. But in this book, the real Casaubon emerges as a genuine literary hero, an intrepid explorer in the world of books. With a flair for storytelling reminiscent of Umberto Eco, Grafton and Weinberg follow Casaubon as he unearths the lost continent of Hebrew learning—and adds this ancient lore to the well-known Renaissance revival of Latin and Greek.

The mystery begins with Mark Pattison’s nineteenth-century biography of Casaubon. Here we encounter the Protestant Casaubon embroiled in intellectual quarrels with the Italian and Catholic orator Cesare Baronio. Setting out to understand the nature of this imbroglio, Grafton and Weinberg discover Casaubon’s knowledge of Hebrew. Close reading and sedulous inquiry were Casaubon’s tools in recapturing the lost learning of the ancients—and these are the tools that serve Grafton and Weinberg as they pore through pre-1600 books in Hebrew, and through Casaubon’s own manuscript notebooks. Their search takes them from Oxford to Cambridge, from Dublin to Cambridge, Massachusetts, as they reveal how the scholar discovered the learning of the Hebrews—and at what cost.

Jean Feraca’s road to self-fulfillment has been as quirky and demanding as the characters in her incredible memoir. A veteran of several decades of public radio broadcasting, Feraca is also a writer and a poet. She is a talk show host beloved for her unique mixture of the humanities, poetry, and journalism, and is the creator of the pioneering international cultural affairs radio program Here on Earth: Radio without Borders.

In this searing memoir, Feraca traces her own emergence. She pulls back the curtain on her private life, revealing unforgettable portraits of the characters in her brawling Italian-American family: Jenny, the grandmother, the devil woman who threw Casey Stengel down an excavation pit; Dolly, the mother, a cross between Long John Silver and the Wife of Bath, who in battling mental illness becomes the scourge of a Lutheran nursing home; and Stephen, the brilliant but troubled older brother, an anthropologist adopted by a Sioux tribe. In a new chapter that reinforces and ties together the book’s exploration of the multiple forms of love, Jean introduces us to Roger, a Wildman and her husband’s best friend with whom she, too, develops an extraordinary intimacy. A selection of fifteen of Feraca’s poems add counterpoint to her engaging prose.

I Live Underwater is the highly anticipated posthumous memoir of Max Nohl, a larger-than-life thrill seeker and treasure hunter who revolutionized deep-sea diving. Recounting harrowing experiences with tangled air-hoses, hungry sharks, untested scientific theories, and painful cases of the bends, Nohl’s vivid narrative shows how his unquenchable thirst for adventure propelled him to transcend fear and become one of the field’s great innovators—shattering the diving record in 1937 as the first person to dive deeper than 400 feet.

Beginning with the disquieting childhood experiences that inspired his obsession with the underwater world, Nohl goes on to discuss his innovative work on the first self-contained diving suit as a student at MIT and his risky experiments in breathing helium to achieve deeper dives. In addition to making vital contributions to the commercial diving industry, Nohl was a pioneer in underwater filming, developing equipment and techniques that were employed in many Hollywood film and television productions.

After Nohl’s sudden death in 1960 in a car accident, his nearly complete memoir sat in the Milwaukee Public Library Archives—unpublished, until now. Accompanying this page-turning text is a dynamic assortment of images, including Nohl’s original pen-and-ink sketches and historic photos of Nohl and his collaborators. A foreword by Wisconsin Historical Society maritime archaeologist Tamara Thomsen provides insights into Nohl’s many important contributions to the diving world and to Wisconsin history and culture.

Includes stories of dives in Lake Michigan (near Milwaukee), the North Atlantic (near Marblehead and Martha’s Vineyard), Walden Pond, the Gulf Coast (near Morgan City, Louisiana, and Panama City, Apalachicola, Wakulla Springs, and Tarpon Springs in Florida), and the Caribbean (near Haiti and the Dominican Republic).

From living among New York's abstract expressionists in the mid-1950s as a young woman to working in the Nicaraguan Ministry of Culture to instill revolutionary values in the media during the Sandinista movement, the story of Randall's life reads like a Hollywood production. Along the way, she edited a bilingual literary journal in Mexico City, befriended Cuban revolutionaries, raised a family, came out as a lesbian, taught college, and wrote over 150 books. Throughout it all, Randall never wavered from her devotion to social justice.

When she returned to the United States in 1984 after living in Latin America for twenty-three years, the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service ordered her to be deported for her “subversive writing.” Over the next five years, and with the support of writers, entertainers, and ordinary people across the country, Randall fought to regain her citizenship, which she won in court in 1989.

As much as I Never Left Home is Randall's story, it is also the story of the communities of artists, writers, and radicals she belonged to. Randall brings to life scores of creative and courageous people on the front lines of creating a more just world. She also weaves political and social analyses and poetry into the narrative of her life. Moving, captivating, and astonishing, I Never Left Home is a remarkable story of a remarkable woman.

“I regularly decide to quit talking to white people about racism,” writes Joof. Such discussions often feel unproductive, the occasional spark of hope coming at enormous personal cost. But not talking about it is impossible, a betrayal of self. The book is a self-examination as well as societal indictment. It is an open challenge to readers, to hear her as she talks about it, all the time.

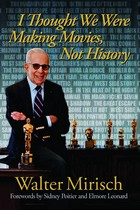

This is a moving, star-filled account of one of Hollywood’s true golden ages as told by a man in the middle of it all. Walter Mirisch’s company has produced some of the most entertaining and enduring classics in film history, including West Side Story, Some Like It Hot, In the Heat of the Night, and The Magnificent Seven. His work has led to 87 Academy Award nominations and 28 Oscars. Richly illustrated with rare photographs from his personal collection, I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History reveals Mirisch’s own experience of Hollywood and tells the stories of the stars—emerging and established—who appeared in his films, including Natalie Wood, John Wayne, Peter Sellers, Sidney Poitier, Steve McQueen, Marilyn Monroe, and many others.

With hard-won insight and gentle humor, Mirisch recounts how he witnessed the end of the studio system, the development of independent production, and the rise and fall of some of Hollywood’s most gifted (and notorious) cultural icons. A producer with a passion for creative excellence, he offers insights into his innovative filmmaking process, revealing a rare ingenuity for placating the demands of auteur directors, weak-kneed studio executives, and troubled screen sirens.

From his early start as a movie theater usher to the presentation of such masterpieces as The Apartment, Fiddler on the Roof, and The Great Escape, Mirisch tells the inspiring life story of his climb to the highest echelon of the American film industry. This book assures Mirisch’s legacy—as Elmore Leonard puts it—as “one of the good guys.”

Best Books for Special Interests, selected by the American Association of School Librarians, and Best Books for General Audiences, selected by the Public Library Association

In this extraordinary autobiography, the legendary Heath creates a “dialogue” with musicians and family members. As in jazz, where improvisation by one performer prompts another to riff on the same theme, I Walked with Giants juxtaposes Heath’s account of his life and career with recollections from jazz giants about life on the road and making music on the world’s stages. His memories of playing with his equally legendary brothers Percy and Albert (aka “Tootie”) dovetail with their recollections.

Heath reminisces about a South Philadelphia home filled with music and a close-knit family that hosted musicians performing in the city’s then thriving jazz scene. Milt Jackson recalls, “I went to their house for dinner…Jimmy’s father put Charlie Parker records on and told everybody that we had to be quiet till dinner because he had Bird on…. When I [went] to Philly, I’d always go to their house.” Today Heath performs, composes, and works as a music educator and arranger. By turns funny, poignant, and extremely candid, Heath’s story captures the rhythms of a life in jazz.

I Write What I Like contains a selection of Biko's writings from 1969, when he became the president of the South African Students' Organization, to 1972, when he was prohibited from publishing. The collection also includes a preface by Archbishop Desmond Tutu; an introduction by Malusi and Thoko Mpumlwana, who were both involved with Biko in the Black Consciousness movement; a memoir of Biko by Father Aelred Stubbs, his longtime pastor and friend; and a new foreword by Professor Lewis Gordon.

Biko's writings will inspire and educate anyone concerned with issues of racism, postcolonialism, and black nationalism.

An archival study of Ida Lupino’s work in film and television directing, writing, producing, and acting from the 1940s to the 1970s.

Though her acting career is well known, Ida Lupino was, until very recently, either unknown or overlooked as an influential director. One of the few female directors in Classical Hollywood, Lupino was the only woman with membership in the Directors Guild of America between 1948 and 1971. Her films were about women without power in society and engaged with highly controversial topics despite Hollywood’s strict production code. Working in a male-dominated field, Lupino was forced to manage her public persona carefully, resisting attempts by the press to paint her solely as a dutiful wife and mother—a continual feminization—just so that she could continue directing.

Filmmaker Alexandra Seros retells the story of Ida Lupino’s career, from actor to director, first in film, then in television, using archival materials from collections housed around the world. The result provides rich insights into three of Lupino’s independently directed films and a number of episodes from her vast television oeuvre. Seros contextualizes this analysis with discussions of gendered labor in the film industry, the rise of consumerism in the United States after World War II, and the expectations put on women in their family lives during the postwar era. Seros’s portrait of Lupino ultimately paints her life and career as an exemplar of collaborative auteurship.

Ideal Beauty reveals the woman behind the mystique, a woman who overcame an impoverished childhood to become a student at the Swedish Royal Dramatic Academy, an actress in European films, and ultimately a Hollywood star. Chronicling her tough negotiations with Louis B. Mayer at MGM, it shows how Garbo carved out enough power in Hollywood to craft a distinctly new feminist screen presence in films like Queen Christina. Banner draws on over ten years of in-depth archival research in Sweden, Germany, France, and the United States to demonstrate how, away from the camera’s glare, Garbo’s life was even more intriguing. Ideal Beauty takes a fresh look at an icon who helped to define female beauty in the twentieth century and provides answers to much-debated questions about Garbo’s childhood, sexuality, career, illnesses and breakdowns, and spiritual awakening.

Identity's Architect is the first comprehensive biography of Erik Erikson, postwar America's most influential psychological thinker, who decisively reshaped our views of human development.

Drawing on private materials and extensive interviews, award-winning historian Lawrence J. Friedman illuminates the relationship between Erikson's personal life and his groundbreaking notion of the life cycle and the identity crisis. A decade in the making, this book is indispensable for anyone who hopes to understand fully the life and intellectual legacy of one of the most significant figures of our time.

Bringing together the best new work oncinemaand stardom in the 1920s, this illustrated collection showcases the range of complex social, institutional, and aesthetic issues at work in American cinema of this time. Attentive to stardom as an ensemble of texts, contexts, and social phenomena stretching beyond the cinema, major scholars provide careful analysis of the careers of both well-known and now forgotten stars of the silent and early sound era—Douglas Fairbanks, Buster Keaton, the Talmadge sisters, Rudolph Valentino, Gloria Swanson, Clara Bow, Colleen Moore, Greta Garbo, Anna May Wong, Emil Jannings, Al Jolson, Ernest Morrison, Noble Johnson, Evelyn Preer, Lincoln Perry, and Marie Dressler.

Spivey follows Paige from his birth in Alabama in 1906 to his death in Kansas City in 1982, detailing the challenges Paige faced battling the color line in America and recounting his tests and triumphs in baseball. He also opens up Paige’s private life during and after his playing days, introducing readers to the man who extended his social, cultural, and political reach beyond the limitations associated with his humble background and upbringing. This other Paige was a gifted public speaker, a talented musician and singer, an excellent cook, and a passionate outdoorsman, among other things.

Paige’s life intertwined with many of the most important issues of the times in U.S. and African American history, including the continuation of the New Negro Movement and the struggle for civil rights. Spivey incorporates interviews with former teammates conducted over twelve years, as well as exclusive interviews with Paige’s son Robert, daughter Pamela, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, and John “Buck” O’Neil to tell the story of a pioneer who helped transform America through the nation’s favorite pastime.

Maintaining an image somewhere between Joe Louis’s public humility and the flamboyant aggression of Jack Johnson, Paige pushed the boundaries of segregation and bridged the racial divide with stellar pitching packaged with slapstick humor. He entertained as he played to win and saw no contradiction in doing so. Game after game, his performance refuted the lie that black baseball was inferior to white baseball. His was a contribution to civil rights of a different kind—his speeches and demonstrations expressed through his performance on the mound.

From his adventures flying for the Allies in World War II to his work as head pilot trainer for Ariana Afghan Airlines, Race has logged more than six decades in the air. I’ll Fly Away tracks his travels around the globe, encompassing his post-war job as crop duster and bush pilot, his thirty-four years as a commercial airline pilot for Pan American World Airways, his consultancy to King Hussein for Royal Jordanian Airlines, and the eight years in which he served as lead pilot for Orbis, an eye hospital on wings that served thirty-one countries. In 1989 Race notably retraced Charles Lindbergh’s 1927 20,000-mile goodwill tour, flying his Spirit of Orbis biplane to all forty-eight of the continental U.S. states.

A remarkable and wholly readable biography of an American original, I’ll Fly Away will be essential for the bookshelf of every aviation enthusiast.

Arriving in the 1990s with a ninth grade education, N. traveled to Chicago where he found access to ESL and GED classes. He eventually attended college and graduate school and became a professional translator.

Despite having a well-paying job, N. was isolated by a lack of legal documentation. Travel concerns made promotions impossible. The simple act of purchasing his girlfriend a beer at a Cubs baseball game caused embarrassment and shame when N. couldn't produce a valid ID. A frustrating contradiction, N. lived in a luxury high-rise condo but couldn't fully live the American dream. He did, however, find solace in the one gift America gave him–-his education. Ultimately, N.'s is the story of the triumph of education over adversity. In Illegal, he debunks the stereotype that undocumented immigrants are freeloaders without access to education or opportunity for advancement. With bravery and honesty, N. details the constraints, deceptions, and humiliations that characterize alien life "amid the shadows."

Looking back over her life from a precocious childhood in Georgia to her painful decline from a series of crippling strokes, McCullers offers poignant and unabashed remembrances of her early writing success, her family attachments, a troubled marriage to a failed writer, and friendships with literary and film luminaries (Gypsy Rose Lee, Richard Wright, Isak Dinesen, John Huston, Marilyn Monroe), and the intense relationships of the important women in her life.

When it came to the Wild West, the nineteenth-century press rarely let truth get in the way of a good story. James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok’s story was no exception. Mythologized and sensationalized, Hickok was turned into the deadliest gunfighter of all, a so-called moral killer, a national phenomenon even while he was alive.

Rather than attempt to tease truth from fiction, coauthors Paul Ashdown and Edward Caudill investigate the ways in which Hickok embodied the culture of glamorized violence Americans embraced after the Civil War and examine the process of how his story emerged, evolved, and turned into a viral multimedia sensation full of the excitement, danger, and romance of the West.

Journalists, the coauthors demonstrate, invented “Wild Bill” Hickok, glorifying him as a civilizer. They inflated his body count and constructed his legend in the midst of an emerging celebrity culture that grew up around penny newspapers. His death by treachery, at a relatively young age, made the story tragic, and dime-store novelists took over where the press left off. Reimagined as entertainment, Hickok’s legend continued to enthrall Americans in literature, on radio, on television, and in the movies, and it still draws tourists to notorious Deadwood, South Dakota.

American culture often embraces myths that later become accepted as popular history. By investigating the allure and power of Hickok’s myth, Ashdown and Caudill explain how American journalism and popular culture have shaped the way Civil War–era figures are remembered and reveal how Americans have embraced violence as entertainment.

Drawn from extensive archival research, Imitation Artist shows how Hoffmann’s life intersected with those of central gures in twentieth-century popular culture and dance, including Florenz Ziegfeld, George M. Cohan, Isadora Duncan, and Ruth St. Denis. Sunny Stalter-Pace discusses the ways in which Hoffmann navigated the complexities of performing gender, race, and national identity at the dawn of contemporary celebrity culture. This book is essential reading for those interested in the history of theater and dance, modernism, women’s history, and copyright.

A classroom staple, Immigrant Voices: New Lives in America, 1773-2000 has been updated with writings that reflect trends in immigration to the United States through the turn of the twenty-first century. New chapters include a selection of letters from Irish immigrants fleeing the famine of the 1840s, writings from an immigrant who escaped the civil war in Liberia during the 1980s, and letters that crossed the U.S.-Mexico border during the late 1980s and early '90s. With each addition editor Thomas Dublin has kept to his original goals, which was to show the commonalities of the U.S. immigrant experience across lines of gender, nation of origin, race, and even time.

Because it examines the lives of women from many social classes and ethnic backgrounds, Immigrant Women in the Settlement of Missouri does much to explain the rich cultural diversity Missouri enjoys today. The photographs and narratives relating to Czech, French, German, Hungarian, Irish, Italian, and Polish life will remind descendants of immigrants that many customs and traditions they grew up practicing have roots in their home countries and will also promote understanding of the customs of other cultures. In addition to the ethnic and class differences that affected these women’s lives, the book also notes the impact of the various eras in which they lived, their education, the circumstances of their migrations, and their destinations across Missouri.

With their engaging and straightforward narrative, Burnett and Luebbering take the reader chronologically through the history of the state from the colonial period to the Civil War and industrialization. Like all Missouri Heritage Readers, this one is presented in an accessible format with abundant illustrations, and it is sure to please both general readers and those engaged in immigrant and women’s studies.

Winner of the Utah Arts Council's Original Writing Competition Book Manuscript Prize in Creative Nonfiction

Winner of the 15 Bytes Book Award for Creative Nonfiction

“This is not a memoir. Rather, this is a fraternal meditation on the question: ‘Are we friends, my brother?’ The story is uncertain, the characters are in flux, the voices are plural, the photographs are as troubled as the prose. This is not a memoir.”

Thus Scott Abbott introduces the reader to his exploration of the life of his brother John, a man who died of AIDS in 1991 at the age of forty. Writing about his brother, he finds he is writing about himself and about the warm-hearted, educated, and homophobic LDS family that forged the core of his identity.

Images and quotations are interwoven with the reflections, as is a critical female voice that questions his assertions and ridicules his rhetoric. The book moves from the starkness of a morgue’s autopsy through familial disintegration and adult defiance to a culminating fraternal conversation. This exquisitely written work will challenge notions of resolution and wholeness.

Bobrikov’s appointment to the Grand Duchy of Finland in 1898 by Nicholas II led to a policy of intensified Russification that ended nearly a century of political equilibrium between the two states. With access to previously unavailable Russian archival material, Polvinen provides a uniquely balanced and informed view of this dramatic new phase in Russian-Finnish relations. Presenting Bobrikov in the overall context of Russian policy toward Finland, Polvinen investigates such issues as Bobrikov’s goals for Finland, the effect of Russian politics on its Finnish policy, and the influence of Russian journalists during this crucial period.

Offering insight into the workings of the Russian government and its borderland policy during a time of rising international tension, Imperial Borderland will attract readers of Baltic, Finnish, Russian, and Scandinavian history. Those with an interest in the continuing importance of nationalism and nationalities policy in this region of the world will also find this book valuable.

By analyzing Hooker’s career, Endersby offers vivid insights into the everyday activities of nineteenth-century naturalists, considering matters as diverse as botanical illustration and microscopy, classification, and specimen transportation and storage, to reveal what they actually did, how they earned a living, and what drove their scientific theories. What emerges is a rare glimpse of Victorian scientific practices in action. By focusing on science’s material practices and one of its foremost practitioners, Endersby ably links concerns about empire, professionalism, and philosophical practices to the forging of a nineteenth-century scientific identity.

A personal journey through the ever-changing natural and cultural history of Lake Superior’s South Shore

Lake Superior’s South Shore is as malleable as it is enduring, its red sandstone cliffs, clay bluffs, and golden sand beaches reshaped by winds and water from season to season—and sometimes from one hour to the next. Generations of people have inhabited the South Shore, harvesting the forests and fish, mining copper, altering the land for pleasure and profit, for better or worse. In Impermanence, author Sue Leaf explores the natural and human histories that make the South Shore what it is, from the gritty port city of Superior, Wisconsin, to the shipping locks at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

For Leaf, what began as a bicycling adventure on the coast of Lake Superior in 1977 turned into a lifelong connection with the area, and her experience, not least as owner of a rustic cabin on a rapidly eroding lakeside cliff, imbues these essays with a passionate sense of place and an abiding curiosity about its past and precarious future. As waves slowly consume the shoreline where her family has spent countless summers, Leaf is forced to confront the complexity of loving a place that all too quickly is being reclaimed by the great lake.

Impermanence is a journey through the South Shore’s story, from the early days of the Anishinaabe and fur traders through the heyday of commercial fishing, lumber camps, and copper mining on the Keweenaw Peninsula to the awakening of the Northland to the perils and consequences of plundering its natural splendor. Noting the geological, ecological, and cultural features of each stop on her tour along the South Shore, Leaf writes about the restoration of the heavily touristed Apostle Islands National Lakeshore to its pristine conditions, even as Lake Superior maintains its allure for ice fishers, kayakers, and long-distance swimmers. She describes efforts to protect the endangered piping plover and to preserve the diverse sand dunes on the Michigan coast, and she observes the slough that supports rare intact wild rice beds central to Anishinaabe culture.

Part memoir, part travelogue, part natural and cultural history, Leaf’s love letter to Lake Superior’s South Shore is an invitation to see this liminal world in all its seasons and guises, to appreciate its ageless, ever-changing wonders and intimate charms.

The Impossible Indian offers a rare, fresh view of Gandhi as a hard-hitting political thinker willing to countenance the greatest violence in pursuit of a global vision that went far beyond a nationalist agenda. Revising the conventional view of the Mahatma as an isolated Indian moralist detached from the mainstream of twentieth-century politics, Faisal Devji offers a provocative new genealogy of Gandhian thought, one that is not rooted in a clichéd alternative history of spiritual India but arises from a tradition of conquest and violence in the battlefields of 1857.

Focusing on his unsentimental engagement with the hard facts of imperial domination, Fascism, and civil war, Devji recasts Gandhi as a man at the center of modern history. Rejecting Western notions of the rights of man, rights which can only be bestowed by a state, Gandhi turned instead to the idea of dharma, or ethical duty, as the true source of the self’s sovereignty, independent of the state. Devji demonstrates that Gandhi’s dealings with violence, guided by his idea of ethical duty, were more radical than those of contemporary revolutionists.

To make sense of this seemingly incongruous relationship with violence, Devji returns to Gandhi’s writings and explores his engagement with issues beyond India’s struggle for home rule. Devji reintroduces Gandhi to a global audience in search of leadership at a time of extraordinary strife as a thinker who understood how life’s quotidian reality could be revolutionized to extraordinary effect.

In this collection, contributors explore how early women journalists contributed to changing cultural understandings of women’s roles, as well as how class and gender politics meshed in the work of particular individuals. They also examine how female journalists adapted to—or challenged—censorship as political structures in Russia shifted. Over the course of this volume, contributors discuss the attitudes of female Russian journalists toward socialism, Russian nationalism, anti-Semitism, women’s rights, and suffrage. Covering the period from the early 1800s to 1917, this collection includes essays that draw from archival as well as published materials and that range from biography to literary and historical analysis of journalistic diaries.

By disrupting conventional ideas about journalism and gender in late Imperial Russia, An Improper Profession should be of vital interest to scholars of women’s history, journalism, and Russian history.

Contributors. Linda Harriet Edmondson, June Pachuta Farris, Jehanne M Gheith, Adele Lindenmeyr, Carolyn Marks, Barbara T. Norton, Miranda Beaven Remnek, Christine Ruane, Rochelle Ruthchild, Mary Zirin

In a Closet Hidden traces Freeman's evolution as a writer, showing how her own inner conflicts repeatedly found expression in her art. As Glasser demonstrates, Freeman's work examined the competing claims of creativity and convention, self-fulfillment and self-sacrifice, spinsterhood and marriage, lesbianism and heterosexuality.

Why would a grown man chase hornets with a thermometer, paint whirligig beetles bright red, or track elephants through the night to fill trash bags with their prodigious droppings? Some might say—to advance science. Bernd Heinrich says—because it’s fun.

Heinrich, author of the much acclaimed Bumblebee Economics, has been playing in the wilds of one continent or another all his life. In the process, he has become one of the world’s foremost physiological ecologists. With In a Patch of Fireweed, he will undoubtedly become one of our foremost writers of popular science.

Part autobiography, part case study in the ways of field biology, In a Patch of Fireweed is an endlessly fascinating account of a scientist’s life and work. For the author, it is an opportunity to report not just his results but the curiosity, humor, error, passion, and competitiveness that feed into the process of discovery. For the reader, it is simply a delight, a rare chance to share the perceptions of an unusual mind fully in tune with the inner workings of nature. Before his years of research in the woodlands and deserts of North America, the New Guinea highlands, and the plains of East Africa, Heinrich had a sense of the wild that few people in this century can know. He tells the whole story, from his refugee childhood hidden in a German forest, eating mice fried in boar fat, to his ongoing research in the woods surrounding his cabin in Maine.

Stone served in Africa with his wife and successfully learned the Yoruba language. He was an intelligent, self-reflective, and reliable observer, making his works important sources of information on Yoruba society before the intervention of European colonialism. In Africa's Forest and Jungle is a rare account of West African culture, made all the more complete by the additional journal entries, letters, and photographs collected in this edition.

p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0in 0in 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

Whether the subject is the plants that grow there, the animals that live there, the rivers that run there, or the people he has known there, Paul Lindholdt’s In Earshot of Water illuminates the Pacific Northwest in vivid detail. Lindholdt writes with the precision of a naturalist, the critical eye of an ecologist, the affection of an apologist, and the self-revelation and self-awareness of a personal essayist in the manner of Annie Dillard, Loren Eiseley, Derrick Jensen, John McPhee, Robert Michael Pyle, and Kathleen Dean Moore.

Exploring both the literal and literary sense of place, with particular emphasis on environmental issues and politics in the far Northwest, Lindholdt weds passages from the journals of Lewis and Clark, the log of Captain James Cook, the novelized memoir of Theodore Winthrop, and Bureau of Reclamation records growing from the paintings that the agency commissioned to publicize its dams in the 1960s and 1970s, to tell ecological and personal histories of the region he knows and loves.

In Lindholdt’s beautiful prose, America’s environmental legacies—those inherited from his blood relatives as well as those from the influences of mass culture—and illuminations of the hazards of neglecting nature’s warning signs blur and merge and reemerge in new forms. Themes of fathers and sons layer the book, as well—the narrator as father and as son—interwoven with a call to responsible social activism with appeals to reason and emotion. Like water itself, In Earshot of Water cascades across boundaries and blends genres, at once learned and literary.

Driven by grit and determination during the Depression, John Ruan parlayed a one-truck business into Ruan Transportation Management Systems, one of the nation’s leading trucking, leasing, and logistics companies. The trucking business made John Ruan one of the wealthiest and most influential people in Iowa and was the foundation for his vast fortune which included interests in insurance, banking, financial services, international trade, and real estate.

In the 1970s and 80s, Ruan led Des Moines’s renaissance with the construction of the 36-story original Ruan Center, the Marriott Hotel tower, and the Two Ruan Center office complex. But his contributions reached far beyond the confines of Iowa. As a philanthropist, Ruan was a long-time sponsor of the World Food Prize, which recognizes the importance of a nutritious and sustainable food supply for all people.

Based on extensive interviews with Ruan, family members, business associates, friends, and colleagues, as well as privately held papers and archives, In for the Long Haul presents a discerning portrait of this hard-charging yet compassionate businessman.

Flandrau, a model of style and worldly sophistication and destined, almost everyone agreed, for greatness, was among the most talented young writers of his generation. His short stories about Harvard in the 1890s were called “the first realistic description of undergraduate life in American colleges” and sold out of the first printing in a few weeks. From 1899 to 1902 Flandrau was among the most popular contributors to the Saturday Evening Post. Alexander Woollcott rated him the best essayist in America. And Viva Mexico!, Flandrau’s account of life on a Mexican coffee plantation, is a classic, perhaps the best travel book ever written by an American. Yet Flandrau turned his back on it all. Financially independent, he chose a solitary, epicurean life in St. Paul, Mexico, Majorca, Paris, and Normandy. In later years, he confined his writing to local newspaper pieces and letters to his small circle of family and friends.

Using excerpts from these newspaper columns and unpublished letters, Larry Haeg has painstakingly recreated the story of this urbane, talented, witty, lazy, enigmatic, supremely private man who never reached the peak of literary success to which his talent might have taken him.

This very readable biography provides a detailed and honest portrayal of Flandrau and his times. It will fascinate readers interested in writers’ life stories and scholars of American literature as well as general readers interested in midwestern literary history.

In Her Father's Eyes is a moving tale about Jewish life and a father's profound love for his only child. By bridging prewar and wartime periods, the diary also provides a rich context for understanding the history from which the Holocaust emerged.

Inspired by the Hank Williams and Leadbelly recordings he heard as a teenager growing up outside of Boston, Jim Rooney began a musical journey that intersected with some of the biggest names in American music including Bob Dylan, James Taylor, Bill Monroe, Muddy Waters, and Alison Krauss. In It for the Long Run: A Musical Odyssey is Rooney's kaleidoscopic first-hand account of more than five decades of success as a performer, concert promoter, songwriter, music publisher, engineer, and record producer.

As witness to and participant in over a half century of music history, Rooney provides a sophisticated window into American vernacular music. Following his stint as a "Hayloft Jamboree" hillbilly singer in the mid-1950s, Rooney managed Cambridge's Club 47, a catalyst of the ‘60’s folk music boom. He soon moved to the Newport Folk Festival as talent coordinator and director where he had a front row seat to Dylan "going electric."

In the 1970s Rooney's odyssey continued in Nashville where he began engineering and producing records. His work helped alternative country music gain a foothold in Music City and culminated in Grammy nominations for singer-songwriters John Prine, Iris Dement, and Nanci Griffith. Later in his career he was a key link connecting Nashville to Ireland's folk music scene.

Writing songs or writing his memoir, Jim Rooney is the consummate storyteller. In It for the Long Run: A Musical Odyssey is his singular chronicle from the heart of Americana.

In 1921 Solomon Orlovski, a Russian Jew born in 1904, emigrated to America and transformed himself into Robert Orlove, a pattern maker in two senses of the term: during the day, he worked in the fur trade in New York and Chicago, making patterns for toys and hats; in his private life he became a self-taught artist who created prints, sketches, and collages in his study. More than sixty years later his son Ben—an anthropologist educated at Harvard and Berkeley—walked through the doorway of the deceased Robert's study and began to explore more than a half century of his father's experiences, thoughts, and emotions as well as his own very different life. His wry, sensitive combination of biography, memoir, and autobiography taps a remarkably rich vein of individual and collective experience in our diverse society.

Ben Orlove's dual narrative constitutes a family history of notable breadth and immediacy. By turns passionate and cool, dramatic and analytic, he excavates his father Robert's lifetime accumulation of diaries, letters, clippings, photographs, and artworks to create a convincing, deeply satisfying portrait that link both father and son.

Volume 1: Ancient African Queens weaves together oral tradition, folk legends and stories, songs and poems, historical accounts, and travelers’ tales from Egypt to southern Africa, from prehistory to the nineteenth century. These women rulers, warriors, and heroines include Amanirenas, the queen of Kush who battled Roman armies and defeated them at Aswan; Daurama, mother of the seven Hausa kingdoms; Amina Kulibali, founder of the Gabu dynasty in Senegal; Ana de Sousa Nzinga, who resisted the Portuguese conquest of Angola; Beatrice Kimpa Vita, a Kongo prophet burned at the stake by Christian missionaries; Nanda, mother of the famous warrior-king Shaka Zulu; and many others.

These extraordinary women's stories, narrated in the style of African oral tradition, are absorbing, informative, and accessible. The abundant illustrations, many of them rare archival images, depict the diversity among Black women and make this volume a unique treasure for every art lover, every school, and every family.

Widely known as the “poor man’s lawyer” in antebellum Boston, John Albion Andrew (1818–1867) was involved in nearly every cause and case that advanced social and racial justice in Boston in the years preceding the Civil War. Inspired by the legacies of John Quincy Adams and Ralph Waldo Emerson, and mentored by Charles Sumner, Andrew devoted himself to the battle for equality. By day, he fought to protect those condemned to the death penalty, women seeking divorce, and fugitives ensnared by the Fugitive Slave Law. By night, he coordinated logistics and funding for the Underground Railroad as it ferried enslaved African Americans northward.

In this revealing and accessible biography, Stephen D. Engle traces Andrew’s life and legacy, giving this important, but largely forgotten, figure his due. Rising to national prominence during the Civil War years as the governor of Massachusetts, Andrew raised the African American regiment known as the Glorious 54th and rallied thousands of soldiers to the Union cause. Upon his sudden death in 1867, a correspondent for Harper’s Weekly wrote, “Not since the news came of Abraham Lincoln’s death were so many hearts truly smitten.”

Through an organizational scheme that incorporates memorabilia from childhood (samplers, Civil War badges), baseball (Billy’s 1891 Philadelphia contract, scorecards), evangelism (cartoons, books such as Monkeys and Missing Links), social issues (KKK ads endorsing Sunday, his Women's Christian Temperance life membership certificate), life style (Arts and Crafts decorative pieces, extensive photos of the family's Mount Hood bungalow), and family relations (his personal possessions and those of his wife, Nell, and their children), In Rare Form brings together the inconsistencies between Sunday’s material world and his spiritual world.

Since Sunday might have objected to a materialistic analysis of his life, Firstenberger has allowed him a say: each section of the book begins with an apt quote from Sunday’s sermons and writings. Firstenberger also includes appendixes providing detailed information on Sunday’s revivals and speaking appearances, his 870,075 documented converts, the members of his evangelistic team, the overall structure of his family, and an extensive bibliography. Acknowledging Sunday’s faults and contradictions alongside his heroic accomplishments, the author presents a wryly insightful and innovative perspective on this larger-than-life figure.

This volume includes many autobiographical writings, diaries, and letters, with Compton providing annotations and introductory material that illuminates these crucial primary sources. This allows readers to take their understanding of this unique group of women to a new level and to drive home that fact that their lives go far beyond the Nauvoo experiment that forever links them to Mormonism’s founding prophet.

The majority of Smith’s wives were younger than he, and one-third were between fourteen and twenty years of age. Another third were already married, and some of the husbands served as witnesses at their own wife’s polyandrous wedding. In addition, some of the wives hinted that they bore Smith children—most notably Sylvia Sessions’s daughter Josephine—although the children carried their stepfather’s surname.

For all of Smith’s wives, the experience of being secretly married was socially isolating, emotionally draining, and sexually frustrating. Despite the spiritual and temporal benefits, which they acknowledged, they found their faith tested to the limit of its endurance. After Smith’s death in 1844, their lives became even more “lonely and desolate.” One even joined a convent. The majority were appropriated by Smith’s successors, based on the Old Testament law of the Levirate, and had children by them, though they considered these guardianships unsatisfying. Others stayed in the Midwest and remarried, while one moved to California. But all considered their lives unhappy, except for the joy they found in their children and grandchildren.

"There I was, standing alone, unable to cry as I said goodbye to Sidimé Laye, my best friend, and to the revolution that had opened the door of modernity for me--the revolution that had invented me." This book gives us the story of a quest for a childhood friend, for the past and present, and above all for an Africa that is struggling to find its future.

In 1996 Manthia Diawara, a distinguished professor of film and literature in New York City, returns to Guinea, thirty-two years after he and his family were expelled from the newly liberated country. He is beginning work on a documentary about Sékou Touré, the dictator who was Guinea's first post-independence leader. Despite the years that have gone by, Diawara expects to be welcomed as an insider, and is shocked to discover that he is not.

The Africa that Diawara finds is not the one on the verge of barbarism, as described in the Western press. Yet neither is it the Africa of his childhood, when the excitement of independence made everything seem possible for young Africans. His search for Sidimé Laye leads Diawara to profound meditations on Africa's culture. He suggests solutions that might overcome the stultifying legacy of colonialism and age-old social practices, yet that will mobilize indigenous strengths and energies.

In the face of Africa's dilemmas, Diawara accords an important role to the culture of the diaspora as well as to traditional music and literature--to James Brown, Miles Davis, and Salif Kéita, to Richard Wright, Spike Lee, and the ancient epics of the griots. And Diawara's journey enlightens us in the most disarming way with humor, conversations, and well-told tales.

Born to a Danish seamstress and a black West Indian cook in one of the Western Hemisphere's most infamous vice districts, Nella Larsen (1891-1964) lived her life in the shadows of America's racial divide. She wrote about that life, was briefly celebrated in her time, then was lost to later generations--only to be rediscovered and hailed by many as the best black novelist of her generation. In his search for Nella Larsen, the "mystery woman of the Harlem Renaissance," George Hutchinson exposes the truths and half-truths surrounding this central figure of modern literary studies, as well as the complex reality they mask and mirror. His book is a cultural biography of the color line as it was lived by one person who truly embodied all of its ambiguities and complexities.

Author of a landmark study of the Harlem Renaissance, Hutchinson here produces the definitive account of a life long obscured by misinterpretations, fabrications, and omissions. He brings Larsen to life as an often tormented modernist, from the trauma of her childhood to her emergence as a star of the Harlem Renaissance. Showing the links between her experiences and her writings, Hutchinson illuminates the singularity of her achievement and shatters previous notions of her position in the modernist landscape. Revealing the suppressions and misunderstandings that accompany the effort to separate black from white, his book addresses the vast consequences for all Americans of color-line culture's fundamental rule: race trumps family.

On a summer day in 1980 in Niederfeulen, Luxembourg, Suzanne Bunkers pored over parish records of her maternal ancestors, immigrants to the rural American Midwest in the mid 1800s. Suddenly, chance led her to the name Simmerl and to the missing piece in the genealogical puzzle that had brought her so far: Susanna Simmerl, Bunkers' paternal great-great-grandmother, who had given birth to an illegitimate daughter in 1856 before coming to America. Finding Susanna was the catalyst for Bunkers' intensely personal book, which blends history, memory, and imagination into a drama of two women's lives within their multigenerational family.

The rich, complex lives of African Americans in Texas were often neglected by the mainstream media, which historically seldom ventured into Houston's Fourth Ward, San Antonio's East Side, South Dallas, or the black neighborhoods in smaller cities. When Bill Minutaglio began writing for Texas newspapers in the 1970s, few large publications had more than a token number of African American journalists, and they barely acknowledged the things of lasting importance to the African American community. Though hardly the most likely reporter—as a white, Italian American transplant from New York City—for the black Texas beat, Minutaglio was drawn to the African American heritage, seeking its soul in churches, on front porches, at juke joints, and anywhere else that people would allow him into their lives. His nationally award-winning writing offered many Americans their first deeper understanding of Texas's singular, complicated African American history.

This eclectic collection gathers the best of Minutaglio's writing about the soul of black Texas. He profiles individuals both unknown and famous, including blues legends Lightnin' Hopkins, Amos Milburn, Robert Shaw, and Dr. Hepcat. He looks at neglected, even intentionally hidden, communities. And he wades into the musical undercurrent that touches on African Americans' joys, longings, and frustrations, and the passing of generations. Minutaglio's stories offer an understanding of the sweeping evolution of music, race, and justice in Texas. Moved forward by the musical heartbeat of the blues and defined by the long shadow of racism, the stories measure how far Texas has come . . . or still has to go.

The position of the pharmacist in the structure of health care in the United States evolved during the middle half of the 19th century, roughly from the founding of the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy in 1821 to the passage of meaningful pharmaceutical legislation in the 1870s. Higby examines the professional life of William Procter, Jr., generally regarded as the “Father of American Pharmacy,” and follows the development of American pharmacy through four decades of Procter’s professional commitment to the field.

Though the Revolutionary United Front (R.U.F.) ostensibly fought its war (1991–2002) against corrupt government, the people of Sierra Leone were its victims. By the time the war was over, more than fifty thousand were dead, thousands more had been maimed, and over one million were displaced. Jackson relates the stories of political leaders and ordinary people trying to salvage their lives and livelihoods in the aftermath of cataclysmic violence. Combining these with his own knowledge of African folklore, history, and politics and with S. B.’s bittersweet memories—of his family’s rich heritage, his imprisonment as a political detainee, and his position in several of Sierra Leone’s post-independence governments—Jackson has created a work of elegiac, literary, and philosophical power.

Inside her family’s apartment, Sidransky knew a warm, secure place. She recalls her earliest memories of seeing words fall from her parents’ hands. She remembers her father entertaining the family endlessly with his stories, and her mother’s story of tying a red ribbon to herself and her infant daughter to know when she needed anything in the night.

Outside the apartment, the cacophonous hearing world greeted Sidransky’s family with stark stares of curiosity as though they were “freaks.” Always upbeat, her proud father still found it hard to earn a living. When Sidransky started school, she was placed in a class for special needs children until the principal realized that she could hear and speak.

Sidransky portrays her family with deep affection and honesty, and her frank account provides a living narrative of the Deaf experience in pre- and post-World War II America. In Silence has become an invaluable chronicle of a special time and place that will affect all who read it for years to come.

The son of a Black mother and white father overcomes family trauma to find the courage of compassion in veterinary practice

Rising to accept a prestigious award, Jody Lulich wondered what to say. Explain how he’d been attracted to veterinary medicine? Describe how caring for helpless, voiceless animals in his own shame and pain provided a lifeline, a chance to heal himself as well? Lulich tells his story in In the Company of Grace, a memoir about finding courage in compassion and strength in healing—and power in finally confronting the darkness of his youth.

Lulich’s white father and Black mother met at a civil rights rally, but love was no defense against their personal demons. His mother’s suicide, in his presence when he was nine years old, and his sometimes brutal father’s subsequent withdrawal set Lulich on a course from the South Side of Chicago to the Tuskegee School of Veterinary Medicine in Alabama to an endowed chair at the University of Minnesota, forever searching for the approval and affection that success could not deliver. Though shadowed by troubling secrets, his memoir also features scenes of surprising light and promise—of the neighbors who take him in, a brother’s unlikely effort to save Christmas, his mother’s memories of the family’s charmed early days, bright moments (and many curious details) of veterinary practice. Most consequentially, at Tuskegee Lulich rents a room in the home of a seventy-five-year-old Black woman named Grace, whose wholehearted adoption of him—and her own stories of the Jim Crow era—finally gives him a sense of belonging and possibility.

Completing his book amid the furor over George Floyd’s murder, Lulich reflects on all the ways that race has shaped his life. In the Company of Grace is a moving testament to the power of compassion in the face of seemingly overwhelming circumstances.

"Kilimanjaro slowly takes shape as the night sounds die, its glaciated peak tinged pink in the early light. A solitary wildebeest stares motionless as if mesmerized by the towering mass; a small caravan of giraffe drifts across the plain in solitary file, necks undulating to the slow rhythm of their gangling stride. There is an inexplicable deja vu about the African savannas, as if some subliminal memory is tweaked by the birthplace of our hominid lineage." --from In the Dust of Kilimanjaro

In the Dust of Kilimanjaro is the extraordinary story of one man's struggle to protect Kenya's wildlife. World-renowned conservationist David Western -- who grew up in Africa and whose life is intertwined with the lives of its animals and indigenous peoples -- presents a history of African wildlife conservation and an intimate glimpse into his life as a global spokesperson and one of Kenya's most prominent citizens.

Beginning with his childhood adventures hunting in rural Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Western describes how and why the African continent came to hold such power over him. In lyrical prose, he recounts the years of solitary fieldwork in and around Amboseli National Park that led to his gradual awakening to what was happening to the animals and people there. His immersion in the culture and ecology of the region made him realize that without an integrated approach to conservation, one that involved people as well as animals, Kenya's most magnificent creatures would be lost forever.

His accounts of his friendships with the Maasai add a personal dimension to the book that gives the reader new appreciation for the centuries-old links between Africa's wildlife and people. Continued coexistence rather than segregation, he argues, offers the best hope for the world's wildlife. Western describes how his unique understanding of the potentially devastating problems in the region helped him pioneer a new approach to global wildlife conservation that balances the needs of people and wildlife without excluding one or the other.

More than an exceptional autobiography, In the Dust of Kilimanjaro is a riveting look at local and global efforts to preserve species and protect ecosystems. It is the definitive story of wildlife conservation in Africa with a strong and timely message about co-existence between humans and animals.

In this captivating memoir, Draitser explores what it means to be a satirist in a country lacking freedom of expression. His experience provides a window into the lives of a generation of artists who were allowed to poke fun and make readers laugh, as long as they toed a narrow, state-approved line. In the Jaws of the Crocodile also includes several of Draitser’s wry pieces translated into English for the first time.

Search and browse the Bentley Historical Library's Michigan Daily Archive, https://digital.bentley.umich.edu/midaily. The free online archive contains stories from 23,000 issues published between 1891 and 2014.

--John U. Bacon, bestselling author of Three and Out: Rich Rodriguez and the Michigan Wolverines in the Crucible of College Football and Endzone: The Rise, Fall, and Return of Michigan Football

—Mary Sue Coleman, President Emerita at the University of Michigan

—James J. Duderstadt, President Emeritus at the University of Michigan

International terrorism expert Roland Jacquard’s In the Name of Osama bin Laden presents a dramatic portrait of the world's most wanted terrorist and his extensive brotherhood--the network of people who operate “in his name.” Published originally in France the very week of September 11, as events in the United States shook the world, the book has become an international bestseller.

Jacquard details how bin Laden became an international emblem of fundamentalist, pan-Islamic, anti-U.S. fervor and the leader of a brotherhood so passionate that devotees who have never met him will act autonomously in his name. The author explains the global character of bin Laden’s organization, elaborating the extent of his sphere of influence in Europe and Asia. Jacquard reveals the construction of bin Laden’s networks—including a profile of his inner circle—and their collaboration with overlapping webs of banking, drug trafficking, religious, and terrorist organizations. He considers the brotherhood’s access to biological, chemical, and nuclear weapons and warns that, with or without bin Laden, this global terrorist force will remain a threat.

Now in English, this edition has been substantially updated in light of recent world events and expanded to include previously unpublished materials, featuring a new introduction and afterword. New documents include an April 2001 interview by the author with bin Laden; a September 24 proclamation by bin Laden to Muslims in Pakistan; and a key page from Dr. Ayman al-Zawahiri’s book justifying eternal jihad, which was smuggled out of Afghanistan in October 2001.

Donohue's experiences are brutal, but his perceptions are poetic. This account of an intelligent and sensitive man in the grip of alcoholism and homelessness challenges our perceptions of those on the margins of American contemporary life.

"Donohue recorded this often-moving account during a four-year period of homelessness caused by his alcoholism. . . . There are many brilliant observations here on a range of topics, including human nature, technology, and capitalism. . . . Donohue's life on the fringe also provides an inside look at the homeless system of overnight shelters, labor offices, and food stamp providers. But, somehow, in spite of all the negatives, a hopeful book emerges."—Booklist

"A startlingly original book. In this confessional age, Donohue's diary becomes a different sort of tell-all, a palimpsest that forces us to extract the author from his own writing. . . . Donohue comes to resemble Swift's Gulliver"—Nicholas Nesson, Boston Phoenix

"Donohue punctuates his account of 'domiciling within the black walls of a mosquito-infested night' with rambling metaphysical asides in the style of an eighteenth-century philosophe."—Molly McQuade, Lingua Franca

"Despite hunger, homelessness, dead-end jobs and abusive drinking, what is most striking about Donohue is his amazing optimism and endurance."—Patrick Markee, Nation

"Donohue is a gifted writer. . . . But what gives [his diary] the breath of life is that it is written by an artist."—Alec Wilkinson, Los Angeles Times Book Review

In the Philippines and Okinawa, the third volume of Colonel William S. Triplet's memoirs, tells of Triplet's experiences during the American occupations in the early years after World War II. Continuing the story from the preceding books of his memoirs, A Youth in the Meuse-Argonne and A Colonel in the Armored Divisions, Triplet takes us to the Philippines, where his duties included rounding up isolated groups of Japanese holdouts, men who refused to believe or admit that their nation had lost the war, and holding them until the time came to transport them back to Japan.

Triplet also had to reorganize his battalions and companies to raise morale, which had plummeted with the end of the war and the seemingly dull tasks of occupation. When he took over his assignment of commanding a regiment in a division, he was dismayed to discover the unmilitary habits of almost everyone, regardless of rank. A strict disciplinarian himself, Colonel Triplet, who had served in both world wars, at one time commanding a four-thousand-man combat group, brought his regiment of garrison troops back into shape in a short time.

Okinawa presented the new challenge of bringing order to an island that had seen the deaths of one hundred thousand civilians. Virtually every building on the island had been leveled, and tens of thousands of Japanese defenders had been killed. Triplet was also obliged to oversee the temporary burial of thirteen thousand U.S. servicemen, both soldiers and sailors.

In the Philippines and Okinawa portrays the ever-changing, very human, and frequently dangerous occupation of two East Asian regions that are still important to American foreign policy. Any reader interested in military history or American history will find this memoir engaging.

As a diary writer imagines shadow readers rifling diary pages, she tweaks images of the self, creating multiple readings of herself, fixed and unfixed. When the readers and potential readers are husbands and publishers, the writer maneuvers carefully in a world of men who are quick to judge and to take offense. She fills the pages with reflections, anecdotes, codes, stories, biographies, and fictions. The diary acts as a site for the writer’s tension, rebellion, and remaking of herself.

In this book Martinson examines the diaries of Virginia Woolf, Katherine Mansfield, Violet Hunt, and Doris Lessing’s fictional character Anna Wulf, and shows that these diaries (and others like them) are not entirely private writings as has been previously assumed. Rather, their authors wrote them knowing they would be read. In these four cases, the audience is the author’s male lover or husband, and Martinson reveals how knowledge of this audience affects the language and content in each diary. Ultimately, she argues, this audience enforces a certain “male censorship” which changes the shape of the revelations, the shape of the writer herself, making it impossible for the female author to be honest in writing about her true self.

Even sophisticated readers often assume that diaries are primarily private. This study interrogates the myth of authenticity and self-revelation in diaries written under the gaze of particular peekers.

In the Realms of Gold is Oliver’s account of his life and work. He writes in a deft and lively style about the circumstances of his early life that shaped his education and outlook: his childhood on a river houseboat in Kashmir, the influential teachers and friends met at Stowe and Cambridge, and his service in World War II as a cryptographer in British intelligence, where he met his first wife, Caroline Linehan. His interest in church history while at Cambridge led him to study the historical effects of Christian missionaries in Africa, and thus his career began.

The core of the book is Oliver’s account of his research travels throughout tropical Africa from the 1940s to the 1980s; his efforts to train and foster African graduate students to teach in African universities; his role in establishing conferences and journals to bring together the work of historians and archaeologists from Europe and Africa; his encounters with political and religious leaders, scholars, soldiers, and storytellers; and the political and economic upheavals of the continent that he witnessed.

In this extensive study of how southern Jews in the United States responded to the Nazi persecution of European Jews, Dan J. Puckett recounts the divisions between Alabama Jews in the early 1930s. As awareness of the horrors of the Holocaust spread, Jews across Alabama from different backgrounds and from Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox traditions worked to bridge their internal divisions in order to mount efforts to save Jewish lives in Europe. Only by leveraging their collective strength were Alabama’s Jews able to sway the opinions of newspaper editors, Christian groups, and the general public as well as lobby local, state, and national political leaders.

Puckett’s comprehensive analysis is enlivened and illustrated by true stories that will fascinate all readers of southern history. One such story concerns the Altneuschule Torah of Prague and describes how the Nazis, during their brutal occupation of Czechoslovakia, confiscated 1,564 Torahs and sacred Judaic objects from communities throughout Bohemia and Moravia as exhibits in a planned museum to the extinct Jewish race. Recovered after the war by the Czech Memorial Scrolls Trust, the Altneuschule Torah was acquired in 1982 by the Orthodox congregation Ahavas Chesed of Mobile. Ahavas Chesed re-consecrated the scroll as an Alabama memorial to Czech Jews who perished in Nazi death camps.

In the Shadow of Hitler illustrates how Alabama’s Jews, in seeking to influence the national and international well-being of Jews, were changed, emerging from the war period with close cultural and religious cooperation that continues today.

In the Shadow of the Bear chronicles the author's return, after a forty-year absence, to the site of his childhood summer vacations at Little Glen Lake in northwestern Lower Michigan's Leelanau peninsula.

The ancient Ojibwa legend that gave a name to the area's most striking geographical feature, the Sleeping Bear Sand Dunes, offers a way of understanding his mother's powerful but sometimes restless force of love and ambition in the family, as well as his father's quieter, often self-sacrificing love. Chapters devoted to the return to Leelanau, to each of his parents, and to his father's family culminate in the narrative of his daughter's 2005 Leelanau wedding.

Jim McGavran tells his story of self-discovery in prose that is alternatively frank and lyrical as he recaptures his bewildered yet enchanted boyhood self, filtered through his consciousness of longing and loss, lending the writing a particular poignancy.

Thomas Mann’s two eldest children, Erika and Klaus, were unconventional, rebellious, and fiercely devoted to each other. Empowered by their close bond, they espoused vehemently anti-Nazi views in a Europe swept up in fascism and were openly, even defiantly, gay in an age of secrecy and repression. Although their father’s fame has unfairly overshadowed their legacy, Erika and Klaus were serious authors, performance artists before the medium existed, and political visionaries whose searing essays and lectures are still relevant today. And, as Andrea Weiss reveals in this dual biography, their story offers a fascinating view of the literary and intellectual life, political turmoil, and shifting sexual mores of their times.

In the Shadow of the Magic Mountain begins with an account of the make-believe world the Manns created together as children—an early sign of their talents as well as the intensity of their relationship. Weiss documents the lifelong artistic collaboration that followed, showing how, as the Nazis took power, Erika and Klaus infused their work with a shared sense of political commitment. Their views earned them exile, and after escaping Germany they eventually moved to the United States, where both served as members of the U.S. armed forces. Abroad, they enjoyed a wide circle of famous friends, including Andre Gide, Christopher Isherwood, Jean Cocteau, and W. H. Auden, whom Erika married in 1935. But the demands of life in exile, Klaus’s heroin addiction, and Erika’s new allegiance to their father strained their mutual devotion, and in 1949 Klaus committed suicide.

Beautiful never-before-seen photographs illustrate Weiss’s riveting tale of two brave nonconformists whose dramatic lives open up new perspectives on the history of the twentieth century.

Originally published to glowing reviews and literary prizes in France in 1985, this revealing diary not only recounts the moving and tragic relationship of its author, Geneviève Bréton, with the rising young nineteenth-century artist Henri Regnault, it also serves as a valuable historical document concerning the social, cultural, and political life of the French Second Empire.

The young Geneviève Bréton began her journal in 1867 as a consolation for the death of her eldest brother, Antoine. She met Regnault soon after on a trip to Rome. Throughout the next four years of their relationship, Bréton eloquently describes the personal, cultural, and political turbulence that affected her life. Writing against the backdrop of France’s fateful conflict with Prussia and the hardships and dangers of the siege of Paris and the Commune, Bréton, with innate candor and lyricism, creates a text that beautifully illuminates French art, literature, family life, society, and politics of the time. Her poignant account of her love for and engagement to Regnault reveals special insight into the life and mind of an extraordinary, though little known, literary talent. At Regnault’s death in 1871 during the Franco–Prussian War, the expression of her anguish is as much testimony to the political and cultural disorder of the time as it is to her own personal tragedy.