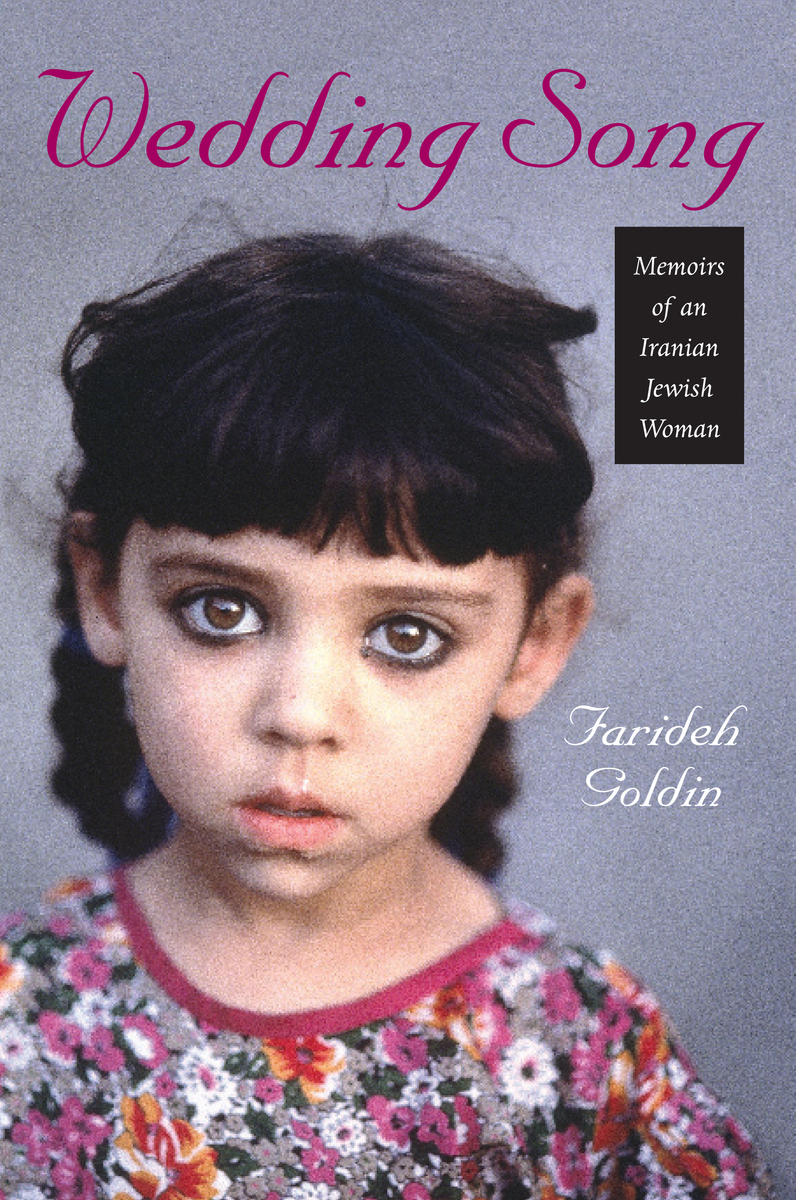

Contents

Prologue

1. Blood Lines

2. My grandmother's House

3. My Education

4. A Place for Me

5. Marriage : A Woman's Dream

6. My New World

Epilogue: September 2001

Prologue

8

Iranian Memoirs

If I had to pick one defining moment in my Iranian life, it would be

5:00 a.m. one Friday in the fall of 1968. I was fifteen. Normally I woke to the sounds of a peddler selling green almonds and fava beans from the sacks hanging on each side of his donkey, the radio screeching the latest news, our only toilet in the hallway flushing, the hustle and bustle of my mother scurrying around to prepare breakfast, to get ready for Shabbat, my grandmother asking me to get to the bakery. But that morning, a scorching odor jolted me out of a deep sleep. At first I thought someone was incinerating the trash outside; I thought my mother had burned the omelet; no, the house must be on fire. Smoke filled my room. I threw off the covers and rushed through the hazy hallway to the kitchen. The entire family was there ; my mother, my grandmother, my married uncle, his wife and children, my single uncle, my single aunt, my sister and two brothers ; trying to get their breakfast, coughing, their eyes irritated.

My father stood near the mud stove, still in his pajama bottoms and a V-neck undershirt. He was chewing his mustache, so I knew he was angry, but at what? Then I saw it. He was throwing books in the fire, my books, the books I had hidden underneath the bed, behind my clothes in the armoire, in the pocket of my winter coat.

It wasn't as if he hadn't warned me about reading. He had heard from cousins at my school; he had caught me reading with a flashlight in bed; he had seen me walk to school with my head in a book. He had warned me just the previous week after an aunt erupted, "Everyone in the community knows that your daughter reads nonstop, corrupting herself, giving us all a bad name."

Instead of obeying, I became more cunning at finding places to hide my books. I couldn't give them up; they were my escape, the keepers of my sanity. I was mostly reading French and Russian classics in translation. I didn't quite understand them because the stories were so absolutely alien to my reality. Nevertheless, they fascinated me, introduced me to unknown cultures and captivating characters. Now curling at the edges, crumbling, the black of the words disappeared into the red of the flames and the gray of the ashes ; exorcised worlds flew in tiny particles from the pyre and swirled in the air. Breathing them, I wondered where I could take my mind now that their magic had fled through the chimney. Perhaps it was time to take my physical self away to the places the books had painted for me.

Although the idea of burning books may jolt many Western readers, I don't want my father to be judged harshly. He wasn't trying to destroy me, but just the opposite. He thought he was saving me by indoctrinating me with the community standards. He didn't know of another person who was addicted to books; neither did I. He told me that I was of marriagable age, that I needed to stay at home to learn to cook and clean since I couldn't resist the corruption of the outside world.

His words weren't new. Most of my male teachers had reiterated the same sentiments in the classroom, telling the few of us who dared to choose mathematics as our major to prepare for marriage instead of wasting educational resources that rightfully belonged to men ; men who as the heads of households would have to support their families. Hearing the same philosophy from my father, however, was much more frightening.

I don't think my father meant those words; I think he wanted to keep me in line by instilling fear of a different fate. Traditionally, a desirable candidate for marriage was a naòve girl with "closed eyes and ears," not one who knew of the world. He didn't want me to ruin my chances for finding the best possible husband. And in the end, my father was the force behind my higher education, insisting that I had to have a college degree to find a better husband, emphasizing that I had to be bilingual since English was the language of progress, the promise of a better future.

Later in the week, when no one was around, I uncovered my last hiding spot in the floor of an armoire, pulled out my journal, and burned the pages in the same stove. Now I was truly alone.

Since Iranian schools didn't promote reading, I didn't have so much as a storybook to read for three years. Then, in 1971, as a first-year student, I stepped inside the Pahlavi University library and scanned with amazement the large collection of books in translation. I promised myself I would finish reading all of them before graduating. Read, I did, but I didn't write again until I had immigrated to the United States, married an American, and had children of my own, children who wanted to hear about my Iranian life. And I, who once had tried so hard to forget my past, went searching for our life stories to record them for my daughters, for the next generation who feared visiting the country of my birth. By then, the 1979 Islamic Revolution had forced a mass exodus of Iranian Jews, leaving nothing but the rubble of Jewish life in Iran. I could extract only fragments of recollection, both what I could recall and memories told to me by family and friends in exile, numb, lost, almost as if still wandering through the desert in a weary exodus from Egypt.

For the last seven years, I have scavenged among the "whys and whens" of our lives only to concede that I cannot fully reconstruct our past. Some of my stories are repeated with the obsession of one who cannot let go of an event, a contemplation. Others are just forgotten, disposed of, or too hurtful to retell, leaving holes in the continuum of our life narratives. These memoirs weave my recollections together with those of my parents and their families, often incomplete and sometimes contradictory.

The tales I have gathered are like the picture frame my father gave me before I left Iran. The frame is made of the intricate designs of Shiraz khatam, decorated with delicate inlaid pieces of wood and ivory arranged painstakingly to create geometric patterns as if each one were a secret map. I wrapped his present well and hid it securely under my garments on the long flight from Iran. I didn't open the package for years. My father's gift didn't fit the dÄcor of any of the apartments I lived in; it was too gaudy, too elaborate, too foreign, too difficult to open and repack as I moved from city to city. When I finally unwrapped it many years later, bits and pieces of ivory and wood were missing, ruining the congruity of its design if looked at closely. I put my wedding picture in it and hung it on our bedroom wall. I can't see the imperfections any longer. When looked at from afar, the designs still make sense; there is a harmonious pattern to their delicate, crushed layout.

This book chronicles my childhood, my family's lives, and the lives of women who went unnoticed in the southern Iranian city of Shiraz. I yearn to acquaint my Western readers with the essence of Jewish life in the shadow of Islam, the magnetism of Western freedoms, culture, and technology against the lulling effect of Persian thoughts, customs, and ethics.

This is my story.

Chapter One

8

Library of Congress Subject Headings for this publication: Goldin, Farideh, 1953- Childhood and youth, Jews Iran Sh�ir�az Biography, Sh�ir�az (Iran) Biography