70 start with L start with L

The first English translation of Greek Theology

The first-century CE North African philosopher Cornutus lived in Rome as a philosopher and is best known today for his surviving work Greek Theology, which explores the origins and names of the Greek gods. However, he was also interested in the language and literature of the poets Persius and Lucan and wrote one of the first commentaries on Virgil. This book collects and translates all of our evidence for Cornutus for the first time and includes the first published English translation of Greek Theology. This collection offers entirely fresh insight into the intellectual world of the first century.

Features

- Translation based on the latest critical text

- The first truly holistic picture of Cornutus’s intellectual profile

- A new account of the early debate over Aristotle’s Categories and the Stoic contribution to it

Nicknamed “La Plonky” by her family after a made-up childhood song, Cota-Cárdenas grew up in California, taught almost exclusively in Arizona, and produced five major works (two novels and three books of poetry) that offer an expansive literary production spanning from the 1960s to today. Her perspectives on Chicana identity, the Chicanx movement, and the sociopolitical climate of Arizona and the larger U.S.-Mexico border region represent a significant contribution to the larger body of Chicanx literature. Additionally, the volume explores her perspectives on issues of gender, sexuality, and identity related to the Chicanx experience over time.

Divided into three major parts, this collection begins with an introduction, followed by two testimonial essays written by the author herself and a longtime colleague, as well as an interview with the author. The second section contains nine essays by well-established literary critics that analyze Cota-Cárdenas’s literary output within a Chicano Movement literary context and offer new readings of Cota-Cárdenas’s fiction and poetry. The third part presents poetry and fiction from Cota-Cárdenas, including an excerpt from a work in progress. As a whole, the collection aims to affirm Margarita Cota-Cárdenas’s significant role in shaping the field of Chicana literature and emphasizes the importance of honoring a celebrated author who wrote a majority of her works in Spanish—one of the few Chicana writers to do so.

Contributors

Laura Elena Belmonte

Margarita Cota-Cárdenas

José R. Flores

Vanessa Fonseca-Chávez

Carolyn González

Gabriella Gutiérrez y Muhs

Manuel M. Martín-Rodríguez

Kirsten F. Nigro

Margarita E. Pignataro

Tey Diana Rebolledo

Jesús Rosales

Charles St-Georges

Javier Villarreal

Lacan in Public argues that Lacan’s contributions to the theory of rhetoric are substantial and revolutionary and that rhetoric is, in fact, the central concern of Lacan’s entire body of work.

Lacan’s conception of rhetoric, Christian Lundberg argues in Lacan in Public, upsets and extends the received wisdom of American rhetorical studies—that rhetoric is a science, rather than an art; that rhetoric is predicated not on the reciprocal exchange of meanings, but rather on the impossibility of such an exchange; and that rhetoric never achieves a correspondence with the real-world circumstances it attempts to describe.

As Lundberg shows, Lacan’s work speaks directly to conversations at the center of current rhetorical scholarship, including debates regarding the nature of the public and public discourses, the materiality of rhetoric and agency, and the contours of a theory of persuasion.

Cáel M. Keegan views the Wachowskis' films as an approach to trans* experience that maps a transgender journey and the promise we might learn "to sense beyond the limits of the given world." Keegan reveals how the filmmakers take up the relationship between identity and coding (be it computers or genes), inheritance and belonging, and how transgender becoming connects to a utopian vision of a post-racial order. Along the way, he theorizes a trans* aesthetic that explores the plasticity of cinema to create new social worlds, new temporalities, and new sensory inputs and outputs. Film comes to disrupt, rearrange, and evolve the cinematic exchange with the senses in the same manner that trans* disrupts, rearranges, and evolves discrete genders and sexes.

One of the very first books to take Stephen King seriously, Landscape of Fear (originally published in 1988) reveals the source of King's horror in the sociopolitical anxieties of the post-Vietnam, post-Watergate era. In this groundbreaking study, Tony Magistrale shows how King's fiction transcends the escapism typical of its genre to tap into our deepest cultural fears: "that the government we have installed through the democratic process is not only corrupt but actively pursuing our destruction, that our technologies have progressed to the point at which the individual has now become expendable, and that our fundamental social institutions-school, marriage, workplace, and the church-have, beneath their veneers of respectability, evolved into perverse manifestations of narcissism, greed, and violence."

Tracing King's moralist vision to the likes of Twain, Hawthorne, and Melville, Landscape of Fear establishes the place of this popular writer within the grand tradition of American literature. Like his literary forbears, King gives us characters that have the capacity to make ethical choices in an imperfect, often evil world. Yet he inscribes that conflict within unmistakably modern settings. From the industrial nightmare of "Graveyard Shift" to the breakdown of the domestic sphere in The Shining, from the techno-horrors of The Stand to the religious fanaticism and adolescent cruelty depicted in Carrie, Magistrale charts the contours of King's fictional landscape in its first decade.

In this book Roger Cardinal surveys the full range of Nash's work, from the ravaged Flanders landscapes of World War One to the spectacular aerial battles of World War Two and the meditative late oils, his final materpieces.

Chude-Sokei makes the crucial argument that Williams’s minstrelsy negotiated the place of black immigrants in the cultural hotbed of New York City and was replicated throughout the African diaspora, from the Caribbean to Africa itself. Williams was born in the Bahamas. When performing the “darky,” he was actually masquerading as an African American. This black-on-black minstrelsy thus challenged emergent racial constructions equating “black” with African American and marginalizing the many diasporic blacks in New York. It also dramatized the practice of passing for African American common among non-American blacks in an African American–dominated Harlem. Exploring the thought of figures such as Booker T. Washington, W. E. B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, and Claude McKay, Chude-Sokei situates black-on-black minstrelsy at the center of burgeoning modernist discourses of assimilation, separatism, race militancy, carnival, and internationalism. While these discourses were engaged with the question of representing the “Negro” in the context of white racism, through black-on-black minstrelsy they were also deployed against the growing international influence of African American culture and politics in the twentieth century.

“Cole does for Miles’s late work what Ian MacDonald’s Revolution in the Head does for the Beatles, examining each album in meticulous detail.”

—Time Out

“As with any good musical biography, Cole . . . made me think again about those albums such as Siesta, You’re Under Arrest, and The Man with the Horn that are now stashed in my attic.”

—London Times

“In the flurry of books since [Miles Davis’s] death, none has dealt in depth with the music of this period. Music writer George Cole fills this gap. . . . a rich and rewarding read.”

—Gazette (Montreal)

“A fascinating book.”

—Mojo

“A singular look into the last stage of Davis’s long, somewhat checkered career gained from various sources, which at the same time gives a picture of the modern music business.”

—Midwest Book Review

“There are large chunks of fresh material here. . . . Fill[s] in quite a few gaps and dismisses blanket condemnations of [Miles’s] pop phase.”

—Jazzwise

“Thank you for telling it like it was!”

—Randy Hall, singer and guitarist

“Very moving, emotional material.”

—Gordon Meltzer, Miles’s last road manager and executive producer of Doo-Bop

The contributors—physicians, philosophers, and literary critics—examine the relevance of Percy’s work to current dilemmas in medical education and health policy. They reflect upon the role doctors and patients play in his novels, his family legacy of depression, how his medical background influenced his writing style, and his philosophy of psychiatry. They contemplate the private ways in which Percy’s work affected their own lives and analyze the author’s tendency to contrast the medical-scientific worldview with a more spiritual one. Assessing Percy’s stature as an author and elucidating the many ways that reading and writing can combine with diagnosing and treating to offer an antidote to despair, they ask what it means to be a doctor, a writer, and a seeker of cures and truths—not just for the body but for the malaise and diseased spirituality of modern times.

This collection will appeal to lovers of literature as well as medical professionals—indeed, anyone concerned with medical ethics and the human side of doctoring.

Contributors. Robert Coles, Brock Eide, Carl Elliott, John D. Lantos, Ross McElwee, Richard Martinez, Martha Montello, David Schiedermayer, Jay Tolson, Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Laurie Zoloth-Dorfman

Beginning in the 1990s, a series of major artists imagined the expansion of photography, intensifying its ideas and effects while abandoning many of its former medium constraints. Simultaneous with this development in contemporary art, however, photography was moving toward total digitalization.

Lateness and Longing presents the first account of a generation of artists—focused on the work of Zoe Leonard, Tacita Dean, Sharon Lockhart, and Moyra Davey—who have collectively transformed the practice of photography, using analogue technologies in a dissident way and radicalizing signifiers of older models of feminist art. All these artists have resisted the transition to the digital in their work. Instead—in what amounts to a series of feminist polemics—they return to earlier, incomplete, or unrealized moments in photography’s history, gravitating toward the analogue basis of photographic mediums. Their work announces that photography has become—not obsolete—but “late,” opened up by the potentially critical forces of anachronism.

Through a strategy of return—of refusing to let go—the work of these artists proposes an afterlife and survival of the photographic in contemporary art, a formal lateness wherein photography finds its way forward through resistance to the contemporary itself.

Gellar-Goad aims to track De Rerum Natura along two paths of satire: first, the broad boulevard of satiric literature from the beginnings of Greek poetry to the plays, essays, and broadcast media of the modern world; and second, the narrower lane of Roman verse satire, satura, beginning with early authors Ennius and Lucilius and closing with Flavian poet Juvenal. Lucilius is revealed as a major, yet overlooked, influence on Lucretius.

By examining how Lucretius’ poem employs the tools of satire, we gain a richer understanding of how it interacts with its purported philosophical program.

Laughter and Civility, the first biographical and scholarly volume to examine and contextualize her dramas, deeply explores how and why influential women are so often excluded from the canon. Lynn R. Wilkinson provides insightful readings into all twenty-five of Gad’s plays and demonstrates how writers and intellectuals of the time, including Georg and Edvard Brandes, took her critically acclaimed work seriously. This volume rightfully reinstates Emma Gad’s work into the repertory of European drama and is crucial for scholars interested in turn‐of‐the‐century Scandinavian drama, literature, culture, and politics.

Interpreting these writers in their larger historical and cultural contexts, Miller reconsiders their formidable artistic, political, and literary contributions to American cultural life in the 1930s. He looks at what was happening in 1932—from depression conditions and politics to chain stores and celebrity culture—to shed light on Wilder’s life, and he shows how actual “little houses” established ideas of home that resonated emotionally for both writers.

In considering each woman’s ties to history, Miller compares Wilder with Frederick Jackson Turner as a frontier mythmaker and examines Lane’s unpublished history of Missouri in the context of a contemporaneous project, Thomas Hart Benton’s famous Jefferson City mural. He also looks at Wilder’s Missouri Ruralist columns to assess her pre–Little House values and writing skills, and he readdresses her literary treatment of Native Americans. A final chapter shows how Wilder’s and Lane’s conservative political views found expression in their work, separating Lane’s more libertarian bent from Wilder’s focus on writing moralist children’s fiction.

These nine thoughtful essays expand the critical discussion on Wilder and Lane beyond the Little House. Miller portrays them as impassioned and dedicated writers who were deeply involved in the historical changes and political challenges of their times—and contends that questions over the books’ authorship do not do justice to either woman’s creative investment in the series. Miller demystifies the aura of nostalgia that often prevents modern readers from seeing Wilder as a real-life woman, and he depicts Lane as a kindred artistic spirit, helping readers better understand mother and daughter as both women and authors.

Brian Brace Taylor draws on extensive archival research to reconstruct each step of the architect's attraction to the commission, his design process and technological innovations, the social and philosophical compatibility of the Salvation Army with Le Corbusier's own ideas for urban planning, and finally, the many modifications required, first to eliminate defects and later to accommodate changes in the services the building provided. Throughout, Taylor focuses on Le Corbusier's environmental, technological, and social intentions as opposed to his strictly formal intentions. He shows that the City of Refuge became primarily a laboratory for the architect's own research and not simply a conventional solution to residents' requirements or the Salvation Army's program.

Considered by many to be the greatest writer of his generation, David Foster Wallace was at the height of his creative powers when he committed suicide in 2008. In a sweeping portrait of Wallace’s writing and thought and as a measure of his importance in literary history, The Legacy of David Foster Wallace gathers cutting-edge, field-defining scholarship by critics alongside remembrances by many of his writer friends, who include some of the world’s most influential authors.

Wachman places at the center of this tradition Sylvia Townsend Warner's achievement in undermining the inhibitions that faced women writing about forbidden love. She discusses Warner's use of crosswriting to transpose the otherwise unrepresentable lives of invisible lesbians into narratives about gay men, destabilizing the borders of race, class, and gender and challenging the codes of expression on which imperialist patriarchy and capitalism depended.

Written by scholars and fiction writers who represent a fascinating range of experience—from a Shakespearean scholar to English professors to a former student of Nordan’s—this is a rich array of essays, poems, and visual arts in tribute to this increasingly important writer. The collection deepens the base of scholarship on Nordan, and contextualizes his work in relation to other important southern writers such as William Faulkner and Eudora Welty.

Nordan was born and raised in Mississippi before moving to Alabama to pursue his Ph.D. at Auburn University. He taught for several years at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville and retired from the University of Pittsburgh, where he was a professor of English. Nordan has written four novels, three collections of short stories, and a memoir entitled Boy with Loaded Gun. His second novel, Wolf Whistle, won the Southern Book Award, and his subsequent novel, The Sharpshooter Blues, won the Notable Book Award from the American Library Association and the Fiction Award from the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters. Nordan is renowned for his distinctive comic writing style, even while addressing more serious personal and cultural issues such as heartbreak, loss, violence, and racism. He transforms tragic characters and events into moments of artistic transcendence, illuminating what he calls the “history of all human beings.”

Li Mengyang (1473–1530) was a scholar-official and man of letters who initiated the literary archaist movement that sought to restore ancient styles of prose and poetry in sixteenth-century China. In this first book-length study of Li in English, Chang Woei Ong comprehensively examines his intellectual scheme and situates Li’s quest to redefine literati learning as a way to build a perfect social order in the context of intellectual transitions since the Song dynasty.

Ong examines Li’s emergence at the distinctive historical juncture of the mid-Ming dynasty, when differences in literati cultures and visions were articulated as a north-south divide (both real and perceived) among Chinese thinkers. Ong argues that this divide, and the ways in which Ming literati compartmentalized learning, is key to understanding Li’s thought and its legacy. Though a northerner, Li became a powerful voice in prose and poetry, in both a positive and negative sense, as he was championed or castigated by the southern literati communities. The southern literati’s indifference toward Li’s other intellectual endeavors—including cosmology, ethics, political philosophy, and historiography—furthered his utter marginalization in those fields.

The full extent of Plutarch’s moral educational program remains largely understudied, at least in those aspects pertaining to women and the gendered other. As a result, scholarship on his views on women have differed significantly in their conclusions, with some scholars suggesting that he is overwhelmingly positive towards women and marriage and perhaps even a “precursor to feminism,” and others arguing that he was rather negative on the issue. Like a Captive Bird: Gender and Virtue in Plutarch is an examination of these educational methods employed in Plutarch’s work to regulate the expression of gender identity in women and men. In six chapters, author Lunette Warren analyzes Plutarch’s ideas about women and gender in Moralia and Lives. The book examines the divergences between real and ideal, the aims and methods of moral philosophy and psychagogic practice as they relate to identity formation, and Plutarch’s theoretical philosophy and metaphysics.

Warren argues that gender is a flexible mode of being that expresses a relation between body and soul, and that gender and virtue are inextricably entwined. Plutarch’s expression of gender is also an expression of a moral condition that signifies relationships of power, Warren claims, especially power relationships between the husband and wife. Uncovered in these texts is evidence of a redistribution of power, which allows some women to dominate other women and, in rare cases, men too. Like a Captive Bird offers a unique and fresh interpretation of Plutarch’s metaphysics which centers gender as one of the organizational principles of nature. It is aimed at scholars of Plutarch, ancient philosophy, and ancient gender studies, especially those who are interested in feminist studies of antiquity.

Mattessich theorizes a new kind of time—subjective displacement—dramatized in the parody, satire, and farce deployed through Pynchon’s oeuvre. In particular, he is interested in showing how this sense of time relates to the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s. Examining this movement as an instance of flight or escape and exposing the beliefs behind it, Mattessich argues that the counterculture’s rejection of the dominant culture ultimately became an act of self-cancellation, a rebellion in which the counterculture found itself defined by the very order it sought to escape. He points to parallels in Pynchon’s attempts to dramatize and enact a similar experience of time in the doubling-back, crisscrossing, and erasure of his writing. Mattessich lays out a theory of cultural production centered on the ethical necessity of grasping one’s own susceptibility to discursive forms of determination.

Reader-friendly and revealing, Listening to Bob Dylan encourages hardcore fans and Dylan-curious seekers alike to rediscover the music legend.

Why did Puritan Christianity repeatedly turn to allegorical forms of representation in spite of its own intolerance of "Allegorical fancies?" Luxon demonstrates that Protestant doctrine itself was a kind of allegory in hiding, one that enabled Puritans to forge a figural view of reality while championing the "literal" and the "historical". He argues that for Puritanism to survive its own literalistic, anti-symbolic, and millenarian challenges, a "fall" back into allegory was inevitable. Representative of this "fall," The Pilgrim's Progress marks the culminating moment at which the Reformation's war against allegory turns upon itself. An essential work for understanding both the history and theory of representation and the work of John Bunyan, Literal Figures skillfully blends historical and critical methods to describe the most important features of early modern Protestant and Puritan culture.

Simons examines the interrelations of Lessing’s literary endings with modes of logical conclusion; he highlights how Goethe’s narrative closures are forestalled by an uncontrollable vital force that was discussed in the sciences of the time; and he reveals that Kleist conceived of literary genres themselves as forms of reasoning. Kleist’s endings, Simons demonstrates, mark the beginning of modernism. Through close readings of these authors and supplemental analyses of works by Walter Benjamin, Friedrich Hölderlin, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, he crafts an elegant theory of conclusions that revises established histories of literary genres and forms.

Harlem Renaissance writer Dorothy West led a charmed life in many respects. Born into a distinguished Boston family, she appeared in Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, then lived in the Soviet Union with a group that included Langston Hughes, to whom she proposed marriage. She later became friends with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who encouraged her to finish her second novel, The Wedding, which became the octogenarian author’s first bestseller.

Literary Sisters reveals a different side of West’s personal and professional lives—her struggles for recognition outside of the traditional literary establishment, and her collaborations with talented African American women writers, artists, and performers who faced these same problems. West and her “literary sisters”—women like Zora Neale Hurston and West’s cousin, poet Helene Johnson—created an emotional support network that also aided in promoting, publishing, and performing their respective works. Integrating rare photos, letters, and archival materials from West’s life, Literary Sisters is not only a groundbreaking biography of an increasingly important author but also a vivid portrait of a pivotal moment for African American women in the arts.

Eaton attempted to disguise her Chinese heritage by writing under a hypothetically Japanese pen name. In legal documents, she usually claimed a "white" racial identity. In her fiction, Eaton portrayed Japanese, Chinese, Irish, and American characters, relying on the accepted stereotypes of the day. Jean Lee Cole shows that the many voices Eaton adopted show her deep preoccupations with "American" identity as a whole. The author attempts to reconcile all of these "voices," examining how Eaton survived in a climate hostile to minority writers in the early twentieth century, and how her seemingly anomalous works conjoin Asian American and American literary history.

Frequent and complex representations of jealousy in early modern Spanish literature offer symbolically rich and often contradictory images. Steven Wagschal examines these occurrences by illuminating the theme of jealousy in the plays of Lope de Vega, the prose of Miguel de Cervantes, and the complex poetry of Luis de Góngora. Noting the prevalence of this emotion in their work, he reveals what jealousy offered these writers at a time when Spain was beginning its long decline.

Beyond their status as classic children’s stories, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books play a significant role in American culture that most people cannot begin to appreciate. Millions of children have sampled the books in school; played out the roles of Laura and Mary; or visited Wilder homesites with their parents, who may be fans themselves. Yet, as Anita Clair Fellman shows, there is even more to this magical series with its clear emotional appeal: a covert political message that made many readers comfortable with the resurgence of conservatism in the Reagan years and beyond.

In Little House, Long Shadow, a leading Wilder scholar offers a fresh interpretation of the Little House books that examines how this beloved body of children’s literature found its way into many facets of our culture and consciousness—even influencing the responsiveness of Americans to particular political views. Because both Wilder and her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, opposed the New Deal programs being implemented during the period in which they wrote, their books reflect their use of family history as an argument against the state’s protection of individuals from economic uncertainty. Their writing emphasized the isolation of the Ingalls family and the family’s resilience in the face of crises and consistently equated self-sufficiency with family acceptance, security, and warmth.

Fellman argues that the popularity of these books—abetted by Lane’s overtly libertarian views—helped lay the groundwork for a negative response to big government and a positive view of political individualism, contributing to the acceptance of contemporary conservatism while perpetuating a mythic West. Beyond tracing the emergence of this influence in the relationship between Wilder and her daughter, Fellman explores the continuing presence of the books—and their message—in modern cultural institutions from classrooms to tourism, newspaper editorials to Internet message boards.

Little House, Long Shadow shows how ostensibly apolitical artifacts of popular culture can help explain shifts in political assumptions. It is a pioneering look at the dissemination of books in our culture that expands the discussion of recent political transformations—and suggests that sources other than political rhetoric have contributed to Americans’ renewed appreciation of individualist ideals.

Think about some commercially successful film masterpieces--The Manchurian Candidate. Seven Days in May. Seconds. Then consider some lesser known, yet equally compelling cinematic achievements--The Fixer. The Gypsy Moths. Path to War. These triumphs are the work of the best known and most highly regarded Hollywood director to emerge from live TV drama in the 1950s--five-time Emmy-award-winner John Frankenheimer.

Although Frankenheimer was a pioneer in the genre of political thrillers who embraced the antimodernist critique of contemporary society, some of his later films did not receive the attention they deserved. Many claimed that at a midpoint in his career he had lost his touch. World-renowned film scholars put this myth to rest in A Little Solitaire, which offers the only multidisciplinary critical account of Frankenheimer's oeuvre. Especially emphasized is his deep and passionate engagement with national politics and the irrepressible need of human beings to assert their rights and individuality in the face of organizations that would reduce them to silence and anonymity.

Acclaimed science fiction scholar Edward James traces Bujold's career, showing how Bujold emerged from fanzine culture to win devoted male and female readers despite working in genres--military SF, space opera--perceived as solely by and for males. Devoted to old-school ideas such as faith in humanity and the desire to probe and do good in the universe, Bujold simultaneously subverted genre conventions and experimented with forms that led her in bold creative directions. As James shows, her iconic hero Miles Vorkosigan--unimposing, physically impaired, self-conscious to a fault--embodied Bujold's thematic concerns. The sheer humanity of her characters, meanwhile, gained her a legion of fans eager to provide her with feedback, expand her vision through fan fiction, and follow her into fantasy.

Contributors to Long Walk Home include novelists like Richard Russo, rock critics like Greil Marcus and Gillian Gaar, and other noted Springsteen scholars and fans such as A. O. Scott, Peter Ames Carlin, and Paul Muldoon. They reveal how Springsteen’s albums served as the soundtrack to their lives while also exploring the meaning of his music and the lessons it offers its listeners. The stories in this collection range from the tale of how “Growin’ Up” helped a lonely Indian girl adjust to life in the American South to the saga of a group of young Australians who turned to Born to Run to cope with their country’s 1975 constitutional crisis. These essays examine the big questions at the heart of Springsteen’s music, demonstrating the ways his songs have resonated for millions of listeners for nearly five decades.

Commemorating the Boss’s seventieth birthday, Long Walk Home explores Springsteen’s legacy and provides a stirring set of testimonials that illustrate why his music matters.

With this collection of essays, the literary record of one of the first and most important men of letters from the South is finally reevaluated from the critical perspective time provides.

William Gilmore Simms (1806-1870) was a poet, critic, novelist, and correspondent whose accomplishment has long been overshadowed by the events of history. As a leading writer and advocate of the antebellum south, Simms suffered from the mercurial judgments of the established publishing and literary circles of the North. Since his death he has slipped into relative obscurity with the inability or unwillingness of most of his critics to separate Simms’s artistic achievements from what have been perceived as flaws in his character.

Together witht he collected letters of Simms—coedited by T.C. Duncan Eaves, to whose memory this book is dedicated—the essays included in Long Years of Neglect can now begin to rectify the damage done over time to the reputation of Simms and his writing, to supersede the options of the past with scholarly and critical appraisal of the work itself, and to offer fresh insight into William Gilmore Simms as a significant and intriguing figure in early American letters.

As editor Guilds speculates in his introduction, “It is conceivable that replacing myth with fact will become fashionable in Simms scholarship, and, even more important, that reading the works—instead of reading the reasons they should be avoided—will become standard practice for Simms as it is for other authors of his stamp.” It was the aim of this book to initiate the realization of that goal.

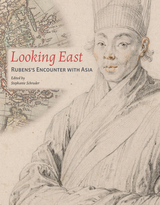

Peter Paul Rubens’s fascinating depiction of a man wearing Korean costume of around 1617, in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum, has been considered noteworthy since it was made. Published to accompany an exhibition of Rubens’s Man in Korean Costume at the J. Paul Getty Museum from March 5 to June 9, 2013, Looking East: Rubens’s Encounter with Asia explores the various facets of Rubens’s compelling drawing of this Asian man that appears in later Rubens works. This large drawing was copied in Rubens’s studio during his own time and circulated as a reproductive print in the eighteenth century. Despite the drawing’s renown, however, the reasons why it was made and whether it actually depicts a specific Asian person remain a mystery. The intriguing story that develops involves a shipwreck, an unusual hat, the earliest trade between Europe and Asia, the trafficking of Asian slaves, and the role of Jesuit missionaries in Asia.

The book’s editor, Stephanie Schrader, traces the interpretations and meanings ascribed to this drawing over the centuries. Could Rubens have actually encountered a particular Korean man who sailed to Europe, or did he instead draw a model wearing Asian clothing or simply hear about such a person? What did Europeans really know about Korea during that period, and what might the Jesuits have had to do with the production of this drawing? All of these questions are asked and explored by the book’s contributors, who look at the drawing from various points of view.

The seventeen essays gathered in this volume take the measure of Vizenor’s achievement. Among the contributors are leading Native American writers Louis Owens, Arnold Krupat, Elaine A. Jahner, and Barry O’Connell.

Returning to Chicago from France, Taft established a bustling studio and began a twenty-one-year career as an instructor at the Art Institute, succeeded by three decades as head of the Midway Studios at the University of Chicago. This triumphant era included ephemeral sculpture for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition; a prolific turn-of-the-century period marked by the gold-medal-winning The Solitude of the Soul; the 1913 Fountain of the Great Lakes; the 1929 Alma Mater at the University of Illinois; and large-scale projects such as his ambitious program for Chicago's Midway with the monumental Fountain of Time. In addition, the book charts Taft's mentoring of women artists, including the so-called White Rabbits at the World's Fair, many of whom went on to achieve artistic success.

Lavishly illustrated with color images of Taft's most celebrated works, Lorado Taft: The Chicago Years completes the first major study of a great American artist.

The modernist novel sought to escape what Virginia Woolf called the “tyranny” of plot. Yet even as twentieth-century writers pushed against the constraints of plot-driven Victorian novels, plot kept its hold on them through the influence of another medium: the cinema. Focusing on the novels of Nella Larsen, Djuna Barnes, and William Faulkner—writers known for their affinities and connections to classical Hollywood—Pardis Dabashi links the moviegoing practices of these writers to the tensions between the formal properties of their novels and the characters in them. Even when they did not feature outright happy endings, classical Hollywood films often provided satisfying formal resolutions and promoted normative social and political values. Watching these films, modernist authors were reminded of what they were leaving behind—both formally and in the name of aesthetic experimentalism—by losing the plot.

R. Dixon Smith has captured the enchanting story of the well known pulp writer Carl Jacobi. Jacobi wrote many fantasy and weird tales, while leading a somewhat bizarre yet magical life.

In this volume, edited by Andreas Schönle, contributors extend Lotman's theories to a number of fields. Focusing on his less frequently studied later period, Lotman and Cultural Studies engages with such ideas as the "semiosphere," the fluid, dynamic semiotic environment out of which meaning emerges; "auto-communication," the way in which people create narratives about themselves that in turn shape their self-identity; change, as both gradual evolution and an abrupt, unpredictable "explosion"; power; law and mercy; Russia and the West; center and periphery.

As William Mills Todd observes in his afterword, the contributors to this volume test Lotman's legacy in a new context: "Their research agendas-Iranian and American politics, contemporary Russian and Czech politics, sexuality and the body-are distant from Lotman's own, but his concepts and awareness yield invariably illuminating results."

Leta E. Miller and Fredric Lieberman take readers into Harrison's rich world of cross-fertilization through an exploration of his outspoken stance on pacifism, gay rights, ecology, and respect for minorities--all major influences on his musical works. Though Harrison was sometimes accused by contemporaries of "cultural appropriation," Miller and Lieberman make it clear why musicians and scholars alike now laud him as an imaginative pioneer for his integration of Asian and Western musics. They also delve into Harrison's work in the development of the percussion ensemble, his use of found and invented instruments, and his explorations of alternative tuning systems. An accompanying compact disc of representative recordings allows readers to examine Harrison's compositions in further detail.

Kahn’s Nordic and European ties are emphasized in this study that also covers his early childhood in Estonia, his travels, and his relationships with other architects, including the Norwegian architect Arne Korsmo.

The authors have gathered personal reflections, archival material, and other student work to offer insight into the wisdom that Kahn imparted to his students in his famous masterclass. Louis I. Kahn: The Nordic Latitudes addresses Kahn’s legacy both personally and in terms of the profession, documents a research trip the University of Pennsylvania’s Louis I. Kahn Collection, and confronts the affiliation of Kahn’s work with postmodernism.

Known for her commentary on the issue of temporality in art, Bal argues that art must be understood in relationship to the present time of viewing as opposed to the less-immediate contexts of what has preceded the viewing, such as the historical past of influences and art movements, biography and interpretation. In ten short chapters, or "takes," Bal demonstrates that the closer the engagement with the work of art, the more adequate the result of the analysis. She also confronts issues of biography and autobiography—key themes in Bourgeois's work—and evaluates the consequences of "ahistorical" experiences for art criticism, drawing on diverse sources such as Bernini and Benjamin, Homer and Eisenstein.

This short, beautiful book offers both a theoretical model for analyzing art "out of context" and a meditation on a key work by one of the most engaging artists of our era.

Scholars who have come to view Blake as a visionary whose work followed nonlinear processes have advanced the notion that his artistic achievement defies conventional interpretation. Love and Logic challenges the tendency in postmodern criticism to see authors and readers as confined by history, language, and logic, denied the ability discover truth or to communicate it in determinate form. Love and Logic emphasizes Blake's ambitious quest for truth, his desire to keep telling the story of human and divine love until he got it right, using all the strategies of logic available to him.

As a pandemic swept across fourteenth-century Europe, the Decameron offered the ill and grieving a symphony of life and love.

For Florentines, the world seemed to be coming to an end. In 1348 the first wave of the Black Death swept across the Italian city, reducing its population from more than 100,000 to less than 40,000. The disease would eventually kill at least half of the population of Europe. Amid the devastation, Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron was born. One of the masterpieces of world literature, the Decameron has captivated centuries of readers with its vivid tales of love, loyalty, betrayal, and sex. Despite the death that overwhelmed Florence, Boccaccio’s collection of novelle was, in Guido Ruggiero’s words, a “symphony of life.”

Love and Sex in the Time of Plague guides twenty-first-century readers back to Boccaccio’s world to recapture how his work sounded to fourteenth-century ears. Through insightful discussions of the Decameron’s cherished stories and deep portraits of Florentine culture, Ruggiero explores love and sexual relations in a society undergoing convulsive change. In the century before the plague arrived, Florence had become one of the richest and most powerful cities in Europe. With the medieval nobility in decline, a new polity was emerging, driven by Il Popolo—the people, fractious and enterprising. Boccaccio’s stories had a special resonance in this age of upheaval, as Florentines sought new notions of truth and virtue to meet both the despair and the possibility of the moment.

Widely recognized as modern China’s preeminent man of letters, Lu Xun (1881–1936) is revered as the voice of a nation’s conscience, a writer comparable to Shakespeare and Tolstoy in stature and influence. Gloria Davies’s portrait now gives readers a better sense of this influential author by situating the man Mao Zedong hailed as “the sage of modern China” in his turbulent time and place.

In Davies’s vivid rendering, we encounter a writer passionately engaged with the heady arguments and intrigues of a country on the eve of revolution. She traces political tensions in Lu Xun’s works which reflect the larger conflict in modern Chinese thought between egalitarian and authoritarian impulses. During the last phase of Lu Xun’s career, the so-called “years on the left,” we see how fiercely he defended a literature in which the people would speak for themselves, and we come to understand why Lu Xun continues to inspire the debates shaping China today.

Although Lu Xun was never a Communist, his legacy was fully enlisted to support the Party in the decades following his death. Far from the apologist of political violence portrayed by Maoist interpreters, however, Lu Xun emerges here as an energetic opponent of despotism, a humanist for whom empathy, not ideological zeal, was the key to achieving revolutionary ends. Limned with precision and insight, Lu Xun’s Revolution is a major contribution to the ongoing reappraisal of this foundational figure.

Until now, no study has attempted to connect the Latin translators and imitators of Lucian with his wider European influence. In Lucian and the Latins, David Marsh describes how Renaissance authors rediscovered the comic writings of Lucian. He traces how Lucianic themes and structures made an essential contribution to European literature beginning with a survey of Latin translations and imitations, which gave new direction to European letters in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The Lucianic dialogues of the dead and dialogues of the gods were immensely popular, despite the religious backlash of the sixteenth century. The paradoxical encomium, represented by Lucian's "The Fly" and "The Parasite," inspired so-called serious humanists like Leonardo Bruni and Guarino of Verona. Lucian's "True Story" initiated the genre of the fantastic journey, which enjoyed considerable popularity during the Renaissance age of discovery. Humanist descendants of this work include Thomas More's Utopia and much of Rabelais' Pantagruel.

Lucian and the Latins will attract readers interested in a wide variety of subjects: the classical tradition, the early Italian Renaissance, the origins of modern European literature, and the uses of humor and satire as instruments of cultural critique.

David Marsh is Professor of Italian, Rutgers University.

In Lucian's Laughing Gods, author Inger N. I. Kuin argues that in ancient Greek thought, comedic depictions of divinities were not necessarily desacralizing. In religion, laughter was accommodated to such an extent as to actually be constituent of some ritual practices, and the gods were imagined either to reciprocate or push back against human laughter—they were never deflated by it. Lucian uses the gods as comic characters, but in doing so, he does not automatically negate their power. Instead, with his depiction of the gods and of how they relate to humans—frivolous, insecure, callous—Lucian challenges the dominant theologies of his day as he refuses to interpret the gods as ethical models. This book contextualizes Lucian’s comedic performances in the intellectual life of the second century CE Roman East broadly, including philosophy, early Christian thought, and popular culture (dance, fables, standard jokes, etc.). His texts are analyzed as providing a window onto non-elite attitudes and experiences, and methodologies from religious studies and the sociology of religion are used to conceptualize Lucian’s engagement with the religiosity of his contemporaries.

Drawing on interviews with Ulitskaya and sources not readily available to Western scholars, Elizabeth A. Skomp and Benjamin M. Sutcliffe explore the ethical ideals that make Ulitskaya’s novels resonate in today’s Russia—tolerance, sincerity, and diversity—and examine how she uses innovative imagery to personalize history through a focus on body and kinship. This is essential reading for anyone interested in contemporary Russian literature and society.

The turbulent years of the 1930s were of profound importance in the life of Spanish film director Luis Buñuel (1900–1983). He joined the Surrealist movement in 1929 but by 1932 had renounced it and embraced Communism. During the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), he played an integral role in disseminating film propaganda in Paris for the Spanish Republican cause.

Luis Buñuel: The Red Years, 1929–1939 investigates Buñuel’s commitment to making the politicized documentary Land without Bread (1933) and his key role as an executive producer at Filmófono in Madrid, where he was responsible in 1935–36 for making four commercial features that prefigure his work in Mexico after 1946. As for the republics of France and Spain between which Buñuel shuttled during the 1930s, these became equally embattled as left and right totalitarianisms fought to wrest political power away from a debilitated capitalism.

Where it exists, the literature on this crucial decade of the film director’s life is scant and relies on Buñuel’s own self-interested accounts of that complex period. Román Gubern and Paul Hammond have undertaken extensive archival research in Europe and the United States and evaluated Buñuel’s accounts and those of historians and film writers to achieve a portrait of Buñuel’s “Red Years” that abounds in new information.

Walt Whitman stands freshly illuminated in this powerful portrait of the poet responding to his times.

Whitman’s idealistic expectations of democracy were painfully eroded by the rapidly expanding urban capitalism that, before the Civil War, increasingly threatened the economic and political power of the ordinary American. His poetry during this, his most fruitful period, became the indispensable medium allowing him to adjust to these developments. He succeeded in portraying this modern society as an invigorating natural extension of the artisanal order. After the war, however, American capitalism advanced at a pace that made it impossible for Whitman to redeem it through his poetry. His imagination defeated by realities, he invested more and more in dreams of the future, while his poetry turned to the past, Memory emerging as a central figure.

In this many-sided analysis M. Wynn Thomas relates Whitman’s work to American painting of the period; examines the poet’s evocation of nature, which he sometimes saw as a challenge to man’s confidence in himself; documents the revisions and additions Whitman made to Leaves of Grass in order to demonstrate that “my Book and the War are One”; and pays sympathetic attention to the postwar poetry, usually slighted.

This first collection of original essays devoted to the poet's work puts many of the best scholars on Sigourney together in one place and in conversation with one another. The volume includes critical essays examining her literary texts as well as essays that unpack Sigourney's participation in the cultural movements of her day. Holding powerful opinions about the role of women in society, Sigourney was not afraid to advocate against government policies that, in her view, undermined the promise of America, even as she was held up as a paragon of American womanhood and middle-class rectitude. The resulting portrait promises to engage readers who wish to know more about Sigourney's writing, her career, and the causes that inspired her.

Along with the volume editors, contributors include Ann Beebe, Paula Bernat Bennett, Janet Dean, Sean Epstein-Corbin, Annie Finch, Gary Kelly, Paul Lauter, Amy J. Lueck, Ricardo Miguel-Alfonso, Jennifer Putzi, Angela Sorby, Joan Wry, and Sandra Zagarell.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press