91 start with A start with A

Weaving their voices through her book, Baker recounts both the dramatic and everyday acts of their resistance. Abortion pills are now playing a critically important role in post-Roe America, providing safe abortion access to tens of thousands of people living in states with abortion bans. Knowing the history of abortion pills is critical to guaranteeing continuing access in the future.

One of the most private decisions a woman can make, abortion is also one of the most contentious topics in American civic life. Protested at rallies and politicized in party platforms, terminating pregnancy is often characterized as a selfish decision by women who put their own interests above those of the fetus. This background of stigma and hostility has stifled women’s willingness to talk about abortion, which in turn distorts public and political discussion. To pry open the silence surrounding this public issue, Sanger distinguishes between abortion privacy, a form of nondisclosure based on a woman’s desire to control personal information, and abortion secrecy, a woman’s defense against the many harms of disclosure.

Laws regulating abortion patients and providers treat abortion not as an acceptable medical decision—let alone a right—but as something disreputable, immoral, and chosen by mistake. Exploiting the emotional power of fetal imagery, laws require women to undergo ultrasound, a practice welcomed in wanted pregnancies but commandeered for use against women with unwanted pregnancies. Sanger takes these prejudicial views of women’s abortion decisions into the twenty-first century by uncovering new connections between abortion law and American culture and politics.

New medical technologies, women’s increasing willingness to talk online and off, and the prospect of tighter judicial reins on state legislatures are shaking up the practice of abortion. As talk becomes more transparent and acceptable, women’s decisions about whether or not to become mothers will be treated more like those of other adults making significant personal choices.

The intimate stories of these "accidental" immigrants broaden conventional notions of home. From a Maori woman who moves to Norway to the daughter of an Iranian diplomat now living in France, Kelley weaves together these stories of the personal and emotional effects of immigration with interdisciplinary discussions drawn from anthropology and psychology. Ultimately, she reveals how the lifelong process of immigration affects each woman's sense of identity and belonging and contributes to better understanding today's globalized society.

Unlike the “tomboy” or the American frontierswoman, this more encompassing figure has been understudied until now. The action-adventure heroine has special relevance today, as scholars are forcefully challenging the once-dominant separate-spheres paradigm and offering alternative interpretations of gender conventions in nineteenth-century America. The hard-body action heroine in our contemporary popular culture is often assumed to be largely a product of the twentieth-century television and film industries (and therefore influenced by the women’s movement); however, physically strong, agile, sometimes violent female figures have appeared in American popular culture and literature for a very long time.

Smith analyzes captivity narratives, war narratives, stories of manifest destiny, dime novels, and tales of seduction to reveal the long literary history of female protagonists who step into traditionally masculine heroic roles to win the day. Smith’s study includes such authors as Herman Mann, Mercy Otis Warren, Catharine Maria Sedgwick, E.D.E.N. Southworth, Edward L. Wheeler, and many more who are due for critical reassessment. In examining the female hero—with her strength, physicality, and violence—in eighteenth-and nineteenth-century American narratives, The Action-Adventure Heroine represents an important contribution to the field of American studies.

Published by the Newark Museum. Distributed worldwide by Rutgers University Press.

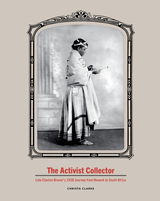

“After twenty-eight years of desire and determination, I have visited Africa, the land of my forefathers.” So wrote Lida Clanton Broner (1895–1982), an African American housekeeper and hairstylist from Newark, New Jersey, upon her return from an extraordinary nine-month journey to South Africa in 1938. This epic trip was motivated not only by Broner’s sense of ancestral heritage, but also a grassroots resolve to connect the socio-political concerns of African Americans with those of black South Africans under the segregationist policies of the time. During her travels, this woman of modest means circulated among South Africa’s Black intellectual elite, including many leaders of South Africa’s freedom struggle. Her lectures at Black schools on “race consciousness and race pride” had a decidedly political bent, even as she was presented as an “American beauty specialist.”

How did Broner—a working class mother—come to be a globally connected activist? What were her experiences as an African American woman in segregated South Africa and how did she further her work after her return? Broner’s remarkable story is the subject of this book, which draws upon a deep visual and documentary record now held in the collection of the Newark Museum of Art. This extraordinary archive includes more than one hundred and fifty objects, ranging from beadwork and pottery to mission school crafts, acquired by Broner in South Africa, along with her diary, correspondence, scrapbooks, and hundreds of photographs with handwritten notations.

In this study of the history of rhetoric education, Susan Kates focuses on the writing and speaking instruction developed at three academic institutions founded to serve three groups of students most often excluded from traditional institutions of higher education in late-nineteenth-and early-twentieth-century America: white middle-class women, African Americans, and members of the working class.

Kates provides a detailed look at the work of those students and teachers ostracized from rhetorical study at traditional colleges and universities. She explores the pedagogies of educators Mary Augusta Jordan of Smith College in Northhampton, Massachusetts; Hallie Quinn Brown of Wilberforce University in Wilberforce, Ohio; and Josephine Colby, Helen Norton, and Louise Budenz of Brookwood Labor College in Katonah, New York.

These teachers sought to enact forms of writing and speaking instruction incorporating social and political concerns in the very essence of their pedagogies. They designed rhetoric courses characterized by three important pedagogical features: a profound respect for and awareness of the relationship between language and identity and a desire to integrate this awareness into the curriculum; politicized writing and speaking assignments designed to help students interrogate their marginalized standing within the larger culture in terms of their gender, race, or social class; and an emphasis on service and social responsibility.

In Adulterous Nations, Tatiana Kuzmic enlarges our perspective on the nineteenth-century novel of adultery, showing how it often served as a metaphor for relationships between the imperialistic and the colonized. In the context of the long-standing practice of gendering nations as female, the novels under discussion here—George Eliot’s Middlemarch, Theodor Fontane’s Effi Briest, and Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, along with August Šenoa’s The Goldsmith’s Gold and Henryk Sienkiewicz’s Quo Vadis—can be understood as depicting international crises on the scale of the nuclear family. In each example, an outsider figure is responsible for the disruption experienced by the family. Kuzmic deftly argues that the hopes, anxieties, and interests of European nations during this period can be discerned in the destabilizing force of adultery. Reading the work of Šenoa and Sienkiewicz, from Croatia and Poland, respectively, Kuzmic illuminates the relationship between the literature of dominant nations and that of the semicolonized territories that posed a threat to them. Ultimately, Kuzmic’s study enhances our understanding of not only these five novels but nineteenth-century European literature more generally.

The contributors focus on specific examples of women pursuing a dual ambition: to gain full civil and political rights and to improve the social conditions of African Americans. Together, the essays challenge us to rethink common generalizations that govern much of our historical thinking about the experience of African American women.

Contributors include Bettina Aptheker, Elsa Barkley Brown, Willi Coleman, Gerald R. Gill, Ann D. Gordon, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Cynthia Neverdon-Morton, Martha Prescod Norman, Janice Sumler-Edmond, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, and Bettye Collier-Thomas.

Anthropologists usually think of domesticity as the activities related to the home and the family. Such activities have complex meanings associated with the sense of space, work, gender, and power. The contributors to this interdisciplinary collection of papers examine how indigenous African notions of domesticity interact with Western notions to transform the meaning of such activities. They explore the interactions of notions of domesticity in a number of settings in the twentieth century and the kinds of personal troubles and public issues these interactions have provoked. They also demonstrate that domesticity, as it emerged in Africa through the colonial encounter, was culturally constructed, and they show how ideologies of work, space, and gender interact with broader political-economic processes.

In her introduction, Hansen explains how the meaning of domesticity has changed and been contested in the West, specifies which of these shifting meanings are relevant in the African context, and summarizes the historical processes that have affected African ideologies of domesticity.

This book explores the history of African womanhood in colonial Kenya. By focussing on key sociocultural institutions and practices around which the lives of women were organized, and on the protracted debates that surrounded these institutions and practices during the colonial period, it investigates the nature of indigenous, mission, and colonial control of African women.

The pertinent institutions and practices include the legal and cultural status of women, clitoridectomy, dowry, marriage, maternity and motherhood, and formal education. By following the effects of the all-pervasive ideological shifts that colonialism produced in the lives of women, the study investigates the diverse ways in which a woman’s personhood was enhanced, diminished, or placed in ambiguous predicaments by the consequences, intended and unintended, of colonial rule as administered by both the colonizers and the colonized. The study thus tries to historicize the reworkings of women’s lives under colonial rule. The transformations that resulted from these reworkings involved the negotiation and redefinition of the meaning of individual liberties and of women’s agency, along with the reconceptualization of kinship relations and of community.

These changes resulted in—and often resulted from—increased mobility for Kenyan women, who were enabled to cross physical, cultural, economic, social, and psychological frontiers that had been closed to them prior to colonial rule. The conclusion to which the experiences of women in colonial Kenya points again and again is that for these women, the exercise of individual agency, whether it was newly acquired or repeatedly thwarted, depended in large measure on the unleashing of forces over which no one involved had control. Over and over, women found opportunities to act amid the conflicting policies, unintended consequences, and inconsistent compromises that characterized colonial rule.

This anthology consists of nine plays by a diverse group of women from throughout the African continent. The plays focus on a wide range of issues, such as cultural differences, AIDS, female circumcision, women's rights to higher education, racial and skin color identity, prostitution as a form of survival for young girls, and nonconformist women resisting old traditions. In addition to the plays themselves, this collection includes commentaries by the playwrights on their own plays, and editor Kathy A. Perkins provides additional commentary and a bibliography of published and unpublished plays by African women.

The playwrights featured are Ama Ata Aidoo, Violet R. Barungi, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Nathalie Etoke, Dania Gurira, Andiah Kisia, Sindiwe Magona, Malika Ndlovu (Lueen Conning), Juliana Okoh, and Nikkole Salter.

Contributors include internationally recognized authors and activists such as Wangari Maathai and Nawal El Saadawi, as well as a host of vibrant new voices from all over the African continent and from the African diaspora. Interdisciplinary in scope, this collection provides an excellent introduction to contemporary African women’s literature and highlights social issues that are particular to Africa but are also of worldwide concern. It is an essential reference for students of African studies, world literature, anthropology, cultural studies, postcolonial studies, and women’s studies.

Outstanding Book, selected by the Public Library Association

Best Books for High Schools, Best Books for Special Interests, and Best Books for Professional Use, selected by the American Association of School Libraries

Andersen shows how women's participation was based on a conception of women's citizenship as indirect and disinterested. Gaining the right to vote, campaign, and run for office transformed women's citizenship; at the same time, women's independent partisan stance, their focus on social welfare concerns, and their use of new political techniques such as lobbying all helped to redefine politics.

This fresh, nuanced analysis of women voters, activists, candidates, and officeholders will interest scholars in political science and women's studies.

"In this rich and engaging book, Kristi Anderson presents a convincing argument that woman suffrage deserves greater scrutiny as a social, cultural, and political force in the development of American electoral and party politics."—Jane Junn, Political Science Quarterly

"Anderson's innovation in this book is to change the dominant question asked about American women's suffrage. . . . This book offers a much-needed corrective to the conventional conception that the enfranchisement of women had no significant effect on American society."—Inderjeet Parmar, Political Studies

"Anderson's book is an excellent treatment . . . and a sterling example of the value of using multiple research methods—also steeped within a deep understanding of context, culture, and historic trends—to explain something as complicated and nuanced as the impact of women's votes after suffrage."—Laura R. Woliver, Journal of Politics

Its title, Afterimages, alludes to the dislocation of time that runs through many of the films and works it discusses as well as to the way we view them. Beginning with a section on the theme of woman as spectacle, a shift in focus leads to films from across the globe, directed by women and about women, all adopting radical cinematic strategies. Mulvey goes on to consider moving image works made for art galleries, arguing that the aesthetics of cinema have persisted into this environment.

Structured in three main parts, Afterimages also features an appendix of ten frequently asked questions on her classic feminist essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in which Mulvey addresses questions of spectatorship, autonomy, and identity that are crucial to our era today.

The legend concerning a popess had first taken written form in the thirteenth century and for several hundred years was more or less accepted. The Reformation, however, polarized discussions of the legend, pitting Catholics, who denied the story’s veracity, against Protestants, who suspected a cover-up and instantly cited Joan as evidence of papal depravity. In this heated environment, writers reimagined Joan variously as a sorceress, a hermaphrodite, and even a noteworthy author.

The Afterlife of Pope Joan examines sixteenth- and seventeenth-century debates concerning the popess’s existence, uncovering the disputants’ historiographic methods, rules of evidence, rhetorical devices, and assumptions concerning what is probable and possible for women and transvestites. Author Craig Rustici then investigates the cultural significance of a series of notions advanced in those debates: the claim that Queen Elizabeth I was a popess in her own right, the charge that Joan penned a book of sorcery, and the curious hypothesis that the popess was not a disguised woman at all but rather a man who experienced a sort of spontaneous sex change.

The Afterlife of Pope Joan draws upon the discourses of religion, politics, natural philosophy, and imaginative literature, demonstrating how the popess functioned as a powerful rhetorical instrument and revealing anxieties and ambivalences about gender roles that persist even today.

Craig M. Rustici is Associate Professor of English at Hofstra University.

Throughout her life, Agatha Tiegel Hanson worked to advance the rights of Deaf people and women, and she was a passionate advocate of sign language rights. Her contributions include creative written works as well as influential treatises. She served in leadership positions at several Deaf organizations and, along with her husband, noted Deaf architect Olof Hanson, she played a vital role in the Deaf cultural life of the time. In Agatha Tiegel Hanson: Our Places in the Sun, author Kathy Jankowski presents a portrait of this trailblazer, and celebrates her impact on the Deaf community and beyond. This biography will be of interest to those already familiar with Tiegel Hanson’s legacy as well as to readers who are discovering her extraordinary life for the first time.

In the mid-1990s, when the United Nations adopted positions affirming a woman's right to be free from bodily harm and to control her own reproductive health, it was both a coup for the international women's rights movement and an instructive moment for nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) seeking to influence UN decision making.

Prior to the UN General Assembly's 1993 Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Violence against Women and the 1994 decision by the UN's Conference on Population and Development to vault women's reproductive rights and health to the forefront of its global population growth management program, there was little consensus among governments as to what constituted violence against women and how much control a woman should have over reproduction. Jutta Joachim tells the story of how, in the years leading up to these decisions, women's organizations got savvy—framing the issues strategically, seizing political opportunities in the international environment, and taking advantage of mobilizing structures—and overcame the cultural opposition of many UN-member states to broadly define the two issues and ultimately cement women's rights as an international cause.

Joachim's deft examination of the documents, proceedings, and actions of the UN and women's advocacy NGOs—supplemented by interviews with key players from concerned parties, and her own participant-observation—reveals flaws in state-centered international relations theories as applied to UN policy, details the tactics and methods that NGOs can employ in order to push rights issues onto the UN agenda, and offers insights into the factors that affect NGO influence. In so doing, Agenda Setting, the UN, and NGOs departs from conventional international relations theory by drawing on social movement literature to illustrate how rights groups can motivate change at the international level.

In the rational modern world, belief in the supernatural seemingly has been consigned to the worlds of entertainment and fantasy. Yet belief in other worldly phenomena, from poltergeists to telepathy, remains strong, as Gillian Bennett's research shows. Especially common is belief in continuing contact with, or the continuing presence of, dead family members. Bennett interviewed women in Manchester, England, asking them questions about ghosts and other aspects of the supernatural. (Her discussion of how her research methods and interview techniques evolved is in itself valuable.) She first published the results of the study in the well-received Traditions of Belief: Women and the Supernatural, which has been widely used in folklore and women's studies courses. "Alas, Poor Ghost!" extensively revises and expands that work. In addition to a fuller presentation and analysis of the original field research and other added material, the author, assisted by Kate Bennett, a gerontological psychologist, presents and discusses new research with a group of women in Leicester, England.

Bennett is interested in more than measuring the extent of belief in other worldly manifestations. Her work explores the relationship between narrative and belief. She anticipated that her questions would elicit from her interviewees not just yes or no replies but stories about their experiences that confirmed or denied notions of the supernatural. The more controversial the subject matter, the more likely individuals were to tell stories, especially if their answers to questions of belief were positive. These were most commonly individualized narratives of personal experience, but they contained many of the traditional motifs and other content, including belief in the supernatural, of legends. Bennett calls them memorates and discusses the cultural processes, including ideas of what is a "proper" experience of the supernatural and a "proper" telling of the story, that make them communal as well as individual. These memorates provide direct and vivid examples of what the storytellers actually believe and disbelieve. In a final section, Bennett places her work in historical context through a discussion of case studies in the history of supernatural belief.

Past biographies, histories, and government documents have ignored Alice Paul's contribution to the women's suffrage movement, but this groundbreaking study scrupulously fills the gap in the historical record. Masterfully framed by an analysis of Paul's nonviolent and visual rhetorical strategies, Alice Paul and the American Suffrage Campaign narrates the remarkable story of the first person to picket the White House, the first to attempt a national political boycott, the first to burn the president in effigy, and the first to lead a successful campaign of nonviolence.

Katherine H. Adams and Michael L. Keene also chronicle other dramatic techniques that Paul deftly used to gain publicity for the suffrage movement. Stunningly woven into the narrative are accounts of many instances in which women were in physical danger. Rather than avoid discussion of Paul's imprisonment, hunger strikes, and forced feeding, the authors divulge the strategies she employed in her campaign. Paul's controversial approach, the authors assert, was essential in changing American attitudes toward suffrage.

Lyall Powers is both a respected scholar of literature and a lifelong friend of Laurence's, having met her when they were students together at Winnipeg's United College in the 1940s. Alien Heart is the first full-length biography of Margaret that combines personal knowledge and insights about Laurence with a study of her work, which often paralleled the events and concerns in her own life.

Drawing on letters, personal correspondence, journals, and interviews, Lyall Powers discusses the struggles and triumphs Laurence experienced in her efforts to understand herself in the roles of writer, wife, mother, and public figure. He portrays a deeply compassionate and courageous woman, who yet felt troubled by conflicting demands. While Laurence's work is not directly autobiographical, Powers illustrates how her writing expressed many of the same dilemmas, and how the resolution her characters achieved in the novels and stories had an impact on Laurence's own life.

Powers provides an in-depth analysis of all Laurence's work, including the early African essays, fiction, and translations, and her books for children, as well as the beloved Manawaka fiction. The study clearly shows the progression and expression of Laurence as a writer of great humanity and conscience.

The stories are by American writers Aracelis González Asendorf, Jacqueline Bishop, Glendaliz Camacho, Learkana Chong, Jennine Capó Crucet, Ramola D., Patricia Engel, Amina Gautier, Manjula Menon, ZZ Packer, Princess Joy L. Perry, Toni Margarita Plummer, Emily Raboteau, Ivelisse Rodriguez, Metta Sáma, Joshunda Sanders, Renee Simms, Mecca Jamilah Sullivan, Hope Wabuke, and Ashley Young; Nigerian writers Unoma Azuah and Chinelo Okparanta; and Chinese writer Xu Xi.

Best Books for General Audiences, selected by the American Association of School Librarians

Best Books for General Audiences, selected by the Public Library Reviewers

From All Anybody Ever Wanted of Me Was to Work...

"Starting around 1950, people stopped raising chickens, milking cows, and raising hogs. They just buy it at the store, ready to eat. A lot buy a steer and have it processed in Dongola and put it in their freezer. What a difference! Girls have got it so easy now. They don't even know what it was like to start out. And I guess my mother's life, when she started out, was as hard again as mine, because they had to make everything by hand. I don't know if it could get any easier for these girls. But they don't know what it was like, and they never will. Everything is packaged. All you do is go to the store and buy you a package and cook it. Automatic washers and dryers. I'm glad they don't have to work like I did. Very glad."

Edith Bradley Rendleman's story of her life in southern Illinois is remarkable in many ways. Recalling the first half of the twentieth century in great detail, she vividly cites vignettes from her childhood as her family moved from farm to farm until settling in 1909 in the Mississippi bottoms of Wolf Lake. She recounts the lives and times of her family and neighbors during an era gone forever.

Remarkable for the vivid details that evoke the past, Rendleman's account is rare in another respect: memoirs of the time—usually written by people from elite or urban families—often reek of nostalgia. But Rendleman's memoir differs from the norm. Born poor in rural southern Illinois, she tells an unvarnished tale of what it was really like growing up on a tenant farm early this century.

All Our Trials explores the organizing, ideas, and influence of those who placed criminalized and marginalized women at the heart of their antiviolence mobilizations. This activism confronted a "tough on crime" political agenda and clashed with the mainstream women’s movement’s strategy of resorting to the criminal legal system as a solution to sexual and domestic violence. Drawing on extensive archival research and first-person narratives, Thuma weaves together the stories of mass defense campaigns, prisoner uprisings, broad-based local coalitions, national gatherings, and radical print cultures that cut through prison walls. In the process, she illuminates a crucial chapter in an unfinished struggle––one that continues in today’s movements against mass incarceration and in support of transformative justice.

In “Charlie,” a new mother tells the story of her confusing attachment to a former mentor, uncovering the deep pain that has largely defined her life. In “The Fathers,” an awkward bachelor party leads to an unexpected moment of overdue connection between the bride’s father and brothers. The title story tracks the drunken monologue of a nihilistic middle-aged man attempting to seduce a young woman into a threesome, while “The Deal” alternates perspectives between a cynical divorced woman and her adult son, the only person with whom she’s been able to sustain a lasting relationship. Relentlessly self-revealing, these characters vacillate between vulnerability and self-protection, exposing the necessity of both. Dark, comic, and altogether unforgettable, All Roads introduces an original voice attuned to the docility of the stingray as well as the ancient spear of its tail.

Patricia Foster’s lyrical yet often painful memoir explores the life of a white middle-class girl who grew up in rural south Alabama in the 1950s and 1960s, a time and place that did not tolerate deviation from traditional gender roles. Her mother raised Foster and her sister as “honorary boys,” girls with the ambition of men but the temperament of women.

An unhappy, intelligent woman who kept a heartbreaking secret from everyone close to her, Foster's mother was driven by a repressed rage that fed her obsession for middle-class respectability. By the time Foster reached age fifteen, her efforts to reconcile the contradictory expectations that she be at once ambitious and restrained had left her nervous and needy inside even while she tried to cultivate the appearance of the model student, sister, and daughter. It was only a psychological and physical breakdown that helped her to realize that she couldn't save her driven, complicated mother and must struggle instead for both understanding and autonomy.

Winner of the American Literary Translators Association 2010 National Translation Award

Petra Hůlová became an overnight sensation when All This Belongs to Me was originally published in Czech in 2002, when the author was just twenty three years old. She has since established herself as one of the most exciting young novelists in Europe today. Writings from an Unbound Europeis proud to publish the first translation of her work in English.

All This Belongs to Me chronicles the lives of three generations of women in a Mongolian family. Told from the point of view of a mother, three sisters, and the daughter of one of the sisters, this story of secrets and betrayals takes us from the daily rhythms of nomadic life on the steppe to the harsh realities of urban alcoholism and prostitution in the capital, Ulaanbaatar. All This Belongs to Me is a sweeping family saga that showcases Hůlová's genius.

Sarah Gillespie Huftalen led an unconventional life for a rural midwestern woman of her time. Born in 1865 near Manchester, Iowa, she was a farm girl who became a highly regarded country school and college teacher; she married a man older than either of her parents, received a college degree later in life, and was committed to both family and career. A gifted writer, she crafted essays, teacher-training guides, and poetry while continuing to write lengthy, introspective entries in her diary, which spans the years from 1873 to 1952. In addition, she gathered extensive information about the quietly tragic life of her mother, Emily, and worked to preserve Emily's own detailed diary.

In more than 3,500 pages, Sarah writes about her multiple roles as daughter, sister, wife, teacher, family historian, and public figure. Her diary reflects the process by which she was socialized into these roles and her growing consciousness of the ways in which these roles intersected. Not only does her diary embody the diverse strategies used by one woman to chart her life's course and to preserve her life's story for future generations, it also offers ample evidence of the diary as a primary form of private autobiography for individuals whose lives do not lend themselves to traditional definitions of autobiography.

Taken together, Emily's and Sarah's extraordinary diaries span nearly a century and thus form a unique mother/daughter chronicle of daily work and thoughts, interactions with neighbors and friends and colleagues, and the destructive family dynamics that dominated the Gillespies. Sarah's consciousness of the abusive relationship between her mother and father haunts her diary, and this dramatic relationship is duplicated in Sarah's relationship with her brother, Henry, Suzanne Bunkers' skillful editing and analysis of Sarah's diary reveal the legacy of a caring, loving mother reflected in her daughter's work as family member, teacher, and citizen.

The rich entries in Sarah Gillespie Huftalen's diary offer us brilliant insights into the importance of female kinship networks in American life, the valued status of many women as family chroniclers, and the fine art of selecting, piecing, stitching, and quilting that characterizes the many shapes of women's autobiographies. Read Sarah's dairy to discover why "all will yet be well."

Taking as a starting point the Italian crisis over immigration in the early 1990s, Merrill examines grassroots interethnic spatial politics among female migrants and Turin feminists in Northern Italy. Using rich ethnographic material, she traces the emergence of Alma Mater—an anti-racist organization formed to address problems encountered by migrant women. Through this analysis, Merrill reveals the dynamics of an alliance consisting of women from many countries of origin and religious and class backgrounds.

Highlighting an interdisciplinary approach to migration and the instability of group identities in contemporary Italy, An Alliance of Women presents migrants grappling with spatialized boundaries amid growing nativist and anti-immigrant sentiment in Western Europe.

Heather Merrill is assistant professor of geography and anthropology at Dickinson College.

Alternative Alcott includes works never before reprinted, including "How I Went Out to Service," "My Contraband," and "Psyche's Art." It also contains Behind a Mask, her most important sensation story; the full and correct text of her last unfinished novel, Diana and Persis; "Transcendental Wild Oats"; Hospital Sketches; and Alcott's other important texts on nineteenth-century social history. This anthology brings together for the first time a variety of Louisa May Alcott's journalistic, satiric, feminist, and sensation texts. Elaine Showalter has provided an excellent introduction and notes to the collection.

Writing about changes in the notion of womanhood, Denise Riley examines, in the manner of Foucault, shifting historical constructions of the category of “women” in relation to other categories central to concepts of personhood: the soul, the mind, the body, nature, the social.

Feminist movements, Riley argues, have had no choice but to play out this indeterminacy of women. This is made plain in their oscillations, since the 1790s, between concepts of equality and of difference. To fully recognize the ambiguity of the category of “women” is, she contends, a necessary condition for an effective feminist political philosophy.

The Roman Catholic church played a dominant role in colonial Brazil, so that women’s lives in the colony were shaped and constrained by the Church’s ideals for pure women, as well as by parallel concepts in the Iberian honor code for women. Records left by Jesuit missionaries, Roman Catholic church officials, and Portuguese Inquisitors make clear that women’s daily lives and their opportunities for marriage, education, and religious practice were sharply circumscribed throughout the colonial period. Yet these same documents also provide evocative glimpses of the religious beliefs and practices that were especially cherished or independently developed by women for their own use, constituting a separate world for wives, mothers, concubines, nuns, and witches.

Drawing on extensive original research in primary manuscript and printed sources from Brazilian libraries and archives, as well as secondary Brazilian historical works, Carole Myscofski proposes to write Brazilian women back into history, to understand how they lived their lives within the society created by the Portuguese imperial government and Luso-Catholic ecclesiastical institutions. Myscofski offers detailed explorations of the Catholic colonial views of the ideal woman, the patterns in women’s education, the religious views on marriage and sexuality, the history of women’s convents and retreat houses, and the development of magical practices among women in that era. One of the few wide-ranging histories of women in colonial Latin America, this book makes a crucial contribution to our knowledge of the early modern Atlantic World.

By juxtaposing the voices of women and men from all walks of life, Sigel finds that women's perceptions of gender relations are complex and often contradictory. Although most women see gender discrimination pervading nearly all social interactions—private as well as public—they do not invariably feel that they personally have been its victims. They want to see discrimination ended, but believe that men do not necessarily share this goal. Women are torn, according to Sigel, between the desire to improve their positions relative to men and the desire to avoid open conflict with them. Their desire not to jeopardize their relations with men, Sigel holds, helps explain women's willingness to accommodate a less-than-egalitarian situation by, for example, taking on the second shift at home or by working harder than men on the job. Sigel concludes that, although men and women agree on the principle of gender equality, definitions as well as practice differ by gender.

This complex picture of how women, while not always content with the status quo, have chosen to accommodate to the world they must face every day is certain to provoke considerable debate.

Amelia Gayle Gorgas (June 1, 1826–January 3, 1913) was the head librarian and postmaster of the University of Alabama for 25 years in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. After the University's original library was burned by Union troops just days before Lee's surrender at Appomattox, Gorgas played a central role in the creation of a new library, expanding the collection from 6,000 to 20,000 volumes. She worked till the age of 80 in 1907, and, in gratitude for her years of service, the University's main library is named in her honor. This book tells her story.

Amelia was the daughter of John Gayle, governor of Alabama from 1831 to 1835, and the wife of Josiah Gorgas, chief of ordnance for the Confederate armies. Their six children included William Crawford Gorgas, surgeon-general of the United States Army. Brought up in the antebellum South, Gorgas nevertheless was a leader in the physical and intellectual reconstruction of the University after the Civil War, both providing some stablizing continuity but also embracing change.

The life of Amelia Gayle Gorgas disproves stereotypes of fragile Southern women. Readers of her story can see in episode after episode the strength, resiliency, and perseverance that the times called for. The extensive and penetrating scholarship of Mary Tabb Johnston and Elizabeth Johnston Lipscomb present Gorgas's story in brisk and enticing detail that will delight readers interesting in the University of Alabama and Southern history.

When she arrived alone in New York in 1924, eighteen-year-old Reisel Thaler resembled the other Yiddish-speaking immigrants from Eastern Europe who accompanied her. Yet she already had an American passport tucked in her scant luggage. Reisel had drawn her first breath on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1905, then was taken back to Galicia (in what is now Poland) by her father before she turned two. She was, as she would boast to the end of her days, “American born.”

The distinguished biographer and critic Rachel M. Brownstein began writing about her mother Reisel during the Trump years, dwelling on the tales she told about her life and the questions they raised about nationalism, immigration, and storytelling. For most of the twentieth century, Brownstein’s mother gracefully balanced her identities as an American and a Jew. Her values, her language, and her sense of timing inform the imagination of the daughter who recalls her in her own old age. The memorializing daughter interrupts, interprets, and glosses, sifting through alternate versions of the same stories using scenes, songs, and books from their time together.

But the central character of this book is Reisel, who eventually becomes Grandma Rose—always watching and judging, singing, baking, and bustling. Living life as the heroine of her own story, she reminds us how to laugh despite tragedy, find our courage, and be our most unapologetically authentic selves.

Mickenberg reveals the complex motives that drew American women to Russia as they sought models for a revolutionary new era in which women would be not merely independent of men, but also equal builders of a new society. Soviet women, after all, earned the right to vote in 1917, and they also had abortion rights, property rights, the right to divorce, maternity benefits, and state-supported childcare. Even women from Soviet national minorities—many recently unveiled—became public figures, as African American and Jewish women noted. Yet as Mickenberg’s collective biography shows, Russia turned out to be as much a grim commune as a utopia of freedom, replete with economic, social, and sexual inequities.

American Girls in Red Russia recounts the experiences of women who saved starving children from the Russian famine, worked on rural communes in Siberia, wrote for Moscow or New York newspapers, or performed on Soviet stages. Mickenberg finally tells these forgotten stories, full of hope and grave disappointments.

The Japanese army’s brutal four-month occupation of the city of Nanking during the 1937 Sino-Japanese War is known, for good reason, as “the rape of Nanking.” As they slaughtered an estimated three hundred thousand people, the invading soldiers raped more than twenty thousand women—some estimates run as high as eighty thousand. Hua-ling Hu presents here the amazing untold story of the American missionary Minnie Vautrin, whose unswerving defiance of the Japanese protected ten thousand Chinese women and children and made her a legend among the Chinese people she served.

Vautrin, who came to be known in China as the “Living Goddess” or the “Goddess of Mercy,” joined the Foreign Christian Missionary Society and went to China during the Chinese Nationalist Revolution in 1912. As dean of studies at Ginling College in Nanking, she devoted her life to promoting Chinese women’s education and to helping the poor.

At the outbreak of the war in July 1937, Vautrin defied the American embassy’s order to evacuate the city. After the fall of Nanking in December, Japanese soldiers went on a rampage of killing, burning, looting, rape, and torture, rapidly reducing the city to a hell on earth. On the fourth day of the occupation, Minnie Vautrin wrote in her diary: “There probably is no crime that has not been committed in this city today. . . . Oh, God, control the cruel beastliness of the soldiers in Nanking.”

When the Japanese soldiers ordered Vautrin to leave the campus, she replied: “This is my home. I cannot leave.” Facing down the blood-stained bayonets constantly waved in her face, Vautrin shielded the desperate Chinese who sought asylum behind the gates of the college. Vautrin exhausted herself defying the Japanese army and caring for the refugees after the siege ended in March 1938. She even helped the women locate husbands and sons who had been taken away by the Japanese soldiers. She taught destitute widows the skills required to make a meager living and provided the best education her limited sources would allow to the children in desecrated Nanking.

Finally suffering a nervous breakdown in 1940, Vautrin returned to the United States for medical treatment. One year later, she ended her own life. She considered herself a failure.

Hu bases her biography on Vautrin’s correspondence between 1919 and 1941 and on her diary, maintained during the entire siege, as well as on Chinese, Japanese, and American eyewitness accounts, government documents, and interviews with Vautrin’s family.

In North America between 1894 and 1930, the rise of the “New Woman” sparked controversy on both sides of the Atlantic and around the world. As she demanded a public voice as well as private fulfillment through work, education, and politics, American journalists debated and defined her. Who was she and where did she come from? Was she to be celebrated as the agent of progress or reviled as a traitor to the traditional family? Over time, the dominant version of the American New Woman became typified as white, educated, and middle class: the suffragist, progressive reformer, and bloomer-wearing bicyclist. By the 1920s, the jazz-dancing flapper epitomized her. Yet she also had many other faces.

Bringing together a diverse range of essays from the periodical press of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Martha H. Patterson shows how the New Woman differed according to region, class, politics, race, ethnicity, and historical circumstance. In addition to the New Woman’s prevailing incarnations, she appears here as a gun-wielding heroine, imperialist symbol, assimilationist icon, entrepreneur, socialist, anarchist, thief, vamp, and eugenicist. Together, these readings redefine our understanding of the New Woman and her cultural impact.

In 1993, white American Fulbright scholar Amy Biehl was killed in a racially motivated attack near Cape Town, after spending months working to promote democracy and women’s rights in South Africa. The ironic circumstances of her death generated enormous international publicity and yielded one of South Africa’s most heralded stories of postapartheid reconciliation. Amy’s parents not only established a humanitarian foundation to serve the black township where she was killed, but supported amnesty for her killers and hired two of the young men to work for the Amy Biehl Foundation. The Biehls were hailed as heroes by Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, and many others in South Africa and the United States—but their path toward healing was neither quick nor easy.

Granted unrestricted access to the Biehl family’s papers, Steven Gish brings Amy and the Foundation to life in ways that have eluded previous authors. He is the first to place Biehl’s story in its full historical context, while also presenting a gripping portrait of this remarkable young woman and the aftermath of her death across two continents.

Amy Levy has risen to prominence in recent years as one of the most innovative and perplexing writers of her generation. Embraced by feminist scholars for her radical experimentation with queer poetic voice and her witty journalistic pieces on female independence, she remains controversial for her representations of London Jewry that draw unmistakably on contemporary antisemitic discourse.

Amy Levy: Critical Essays brings together scholars working in the fields of Victorian cultural history, women’s poetry and fiction, and the history of Anglo-Jewry. The essays trace the social, intellectual, and political contexts of Levy’s writing and its contemporary reception. Working from close analyses of Levy’s texts, the collection aims to rethink her engagement with Jewish identity, to consider her literary and political identifications, to assess her representations of modern consumer society and popular culture, and to place her life and work within late-Victorian cultural debate.

This book is essential reading for undergraduate and postgraduate students offering both a comprehensive literature review of scholarship-to-date and a range of new critical perspectives.

Contributors:

Susan David Bernstein,University of Wisconsin-Madison

Gail Cunningham,Kingston University

Elizabeth F. Evans,Pennslyvania State University–DuBois

Emma Francis,Warwick University

Alex Goody,Oxford Brookes University

T. D. Olverson,University of Newcastle upon Tyne

Lyssa Randolph,University of Wales, Newport

Meri-Jane Rochelson,Florida International University

The opening of free trade agreements in the 1980s caused major economic changes in Mexico and the United States. These economic activities spawned dramatic social changes in Mexican society. One young Mexican woman, Anay Palomeque de Carrillo, rode the tumultuous wave of these economic activities from her rural home in tropical southern Mexico to the factories in the harsh desert lands of Ciudad Juárez during the early years of the city’s notorious violence.

During her years as an education professor at the University of Texas at El Paso, author Elaine Hampton researched Mexican education in border factory (maquiladora) communities. On one trip across the border into Ciudad Juárez, she met Anay, who became her guide in uncovering the complexities of a factory laborer’s experiences in these turbulent times.

Hampton here provides an exploration of education in an era of dramatic social and economic upheaval in rural and urban Mexico. This critical ethnographic case study presents Anay’s experiences in a series of narrative essays addressing the economic, social, and political context of her world. This young Mexican woman leads us through Ciudad Juárez in its most violent years, into women’s experiences in the factories, around family and religious commitments as well as personal illness, and on to her achievement of an education through perseverance and creativity.

First formed in the early twentieth century, the ANC Women’s League has grown into a leading organization in the women’s movement in South Africa. The league has been at the forefront of the nation’s century-long transition from an authoritarian state to a democracy that espouses gender equality as a core constitutional value. It has, indeed, always regarded itself as the women’s movement, frequently asserting its primacy as a vanguard organization and as the only legitimate voice of the women of South Africa. But, as this deeply insightful book shows, the history of the league is a more complicated affair—it was neither the only women’s organization in the political field nor an easy ally for South African feminism.

A true daughter of the West, Angela, born in a tiny mining hamlet in Nevada, came to the Territory of Arizona at the age of twelve. Betty Hammer Joy weaves together the lively story of her grandmother's life by drawing upon Angela's own prodigious writing and correspondence, newspaper archives, and the recollections of family members. Her book recounts the stories Angela told of growing up in mining camps, teaching in territorial schools, courtship, marriage, and a twenty-eight-year career in publishing and printing. During this time, Angela managed to raise three sons, run for public office before women in the nation had the right to vote, serve as Immigration Commissioner in Pinal County, homestead, and mature into an activist for populist agendas and water conservation. As questionable deals took place both within and outside the halls of government, the crusading Angela encountered many duplicitous characters who believed that women belonged at home darning socks, not running a newspaper.

Although Angela's independent papers brought personal hardship and little if any financial reward, after her death in 1952 the newspaper industry paid tribute to this courageous woman by selecting her as the first woman to enter the Arizona Newspaper Hall of Fame. In 1983 she was honored posthumously with another award for women who contributed to Arizona's progress—induction into the Arizona Women's Hall of Fame.

This wide-ranging multidisciplinary anthology presents original material from scholars in a variety of fields, as well as a rare, early article by Virginia Woolf. Exploring the leading edge of the species/gender boundary, it addresses such issues as the relationship between abortion rights and animal rights, the connection between woman-battering and animal abuse, and the speciesist basis for much sexist language. Also considered are the ways in which animals have been regarded by science, literature, and the environmentalist movement. A striking meditation on women and wolves is presented, as is an examination of sexual harassment and the taxonomy of hunters and hunting. Finally, this compelling collection suggests that the subordination and degradation of women is a prototype for other forms of abuse, and that to deny this connection is to participate in the continued mistreatment of animals and women.

Journalist, historian, anthropologist, art critic, and creative writer, Anita Brenner was one of Mexico's most discerning interpreters. Born to a Jewish immigrant family in Mexico a few years before the Revolution of 1910, she matured into an independent liberal who defended Mexico, workers, and all those who were treated unfairly, whatever their origin or nationality.

In this book, her daughter, Susannah Glusker, traces Brenner's intellectual growth and achievements from the 1920s through the 1940s. Drawing on Brenner's unpublished journals and autobiographical novel, as well as on her published writing, Glusker describes the origin and impact of Brenner's three major books, Idols Behind Altars,Your Mexican Holiday, and The Wind That Swept Mexico.

Along the way, Glusker traces Brenner's support of many liberal causes, including her championship of Mexico as a haven for Jewish immigrants in the early 1920s. This intellectual biography brings to light a complex, fascinating woman who bridged many worlds—the United States and Mexico, art and politics, professional work and family life.

With this first scholarly biography of Anna Howard Shaw (1847-1919), Trisha Franzen sheds new light on an important woman suffrage leader who has too often been overlooked and misunderstood.

An immigrant from a poor family, Shaw grew up in an economic reality that encouraged the adoption of non-traditional gender roles. Challenging traditional gender boundaries throughout her life, she put herself through college, worked as an ordained minister and a doctor, and built a tightly-knit family with her secretary and longtime companion Lucy E. Anthony.

Drawing on unprecedented research, Franzen shows how these circumstances and choices both impacted Shaw's role in the woman suffrage movement and set her apart from her native-born, middle- and upper-class colleagues. Franzen also rehabilitates Shaw's years as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, arguing that Shaw's much-belittled tenure actually marked a renaissance of both NAWSA and the suffrage movement as a whole.

Anna Howard Shaw: The Work of Woman Suffrage presents a clear and compelling portrait of a woman whose significance has too long been misinterpreted and misunderstood.

In 1654, Anna Trapnel — a Baptist, Fifth Monarchist, millenarian, and visionary from London — fell into a trance during which she prophesied passionately and at length against Oliver Cromwell and his government. The prophecies attracted widespread public attention, and resulted in an invitation to travel to Cornwall. Her Report and Plea, republished here for the first time, is a lively and engaging firsthand account of the visit, which concluded in her arrest, a court hearing, and imprisonment. Part memoir, part travelogue, and part impassioned defense of her beliefs and actions, the Report and Plea offers vivid and fascinating insight into the life and times of an early modern woman claiming her place at the center of the tumultuous political events of mid-seventeenth-century England.

Lucy Pier Stevens, a twenty-one-year-old woman from Ohio, began a visit to her aunt’s family near Bellville, Texas, on Christmas Day, 1859. Little did she know how drastically her life would change on April 4, 1861, when the outbreak of the Civil War made returning home impossible. Stranded in enemy territory for the duration of the war, how would she reconcile her Northern upbringing with the Southern sentiments surrounding her?

Lucy Stevens’s diary—one of few women’s diaries from Civil War–era Texas and the only one written by a Northerner—offers a unique perspective on daily life at the fringes of America’s bloodiest conflict. An articulate, educated, and keen observer, Stevens took note seemingly of everything—the weather, illnesses, food shortages, parties, church attendance, chores, schools, childbirth, death, the family’s slaves, and political and military news. As she confided her private thoughts to her journal, she unwittingly revealed how her love for her Texas family and the Confederate soldier boys she came to care for blurred her loyalties, even as she continued to long for her home in Ohio. Showing how the ties of heritage, kinship, friendship, and community transcended the sharpest division in US history, this rare diary and Vicki Adams Tongate’s insightful historical commentary on it provide a trove of information on women’s history, Texas history, and Civil War history.

The Other Voice in Early Modern Women: The Toronto Series volume 70

More than half a century after the Universal Declaration of Human Rights defined what a human being is and is entitled to, Catharine MacKinnon asks: Are women human yet? If women were regarded as human, would they be sold into sexual slavery worldwide; veiled, silenced, and imprisoned in homes; bred, and worked as menials for little or no pay; stoned for sex outside marriage or burned within it; mutilated genitally, impoverished economically, and mired in illiteracy--all as a matter of course and without effective recourse?

The cutting edge is where law and culture hurts, which is where MacKinnon operates in these essays on the transnational status and treatment of women. Taking her gendered critique of the state to the international plane, ranging widely intellectually and concretely, she exposes the consequences and significance of the systematic maltreatment of women and its systemic condonation. And she points toward fresh ways--social, legal, and political--of targeting its toxic orthodoxies.

MacKinnon takes us inside the workings of nation-states, where the oppression of women defines community life and distributes power in society and government. She takes us to Bosnia-Herzogovina for a harrowing look at how the wholesale rape and murder of women and girls there was an act of genocide, not a side effect of war. She takes us into the heart of the international law of conflict to ask--and reveal--why the international community can rally against terrorists' violence, but not against violence against women. A critique of the transnational status quo that also envisions the transforming possibilities of human rights, this bracing book makes us look as never before at an ongoing war too long undeclared.

Here, in rich detail, her day-by-day narrative and the editor's annotations bring to life Arizona's territorial capital of Prescott more than one hundred years ago. Lily gives us firsthand accounts of the operation of territorial government; of pressure from Anglo settlers to dispossess Pima Indians from their land; and of efforts by the governor and the army to deal with Indian scares. Here also, underlying her words, are insights into the dynamics of a close-knit Victorian family, shaping the life of an intelligent, educated single woman. As unofficial secretary for her father, Lily was well placed to observe and record an almost constant stream of visitors to the governor's home and office. Observe and record, she did. Her diary is filled with unvarnished images of personalities such as the Goldwaters, General O. B. Willcox, Moses Sherman, Judge Charles Silent, and a host of lesser citizens, politicians, and army officers.

Lily's anecdotes vividly re-create the periodic personality clashes that polarized society (and one full-fledged scandal), the ever-present danger of fire, religious practices (particularly a burial service conducted in Hebrew), and attitudes toward Native Americans and Chinese. On a more personal level, the reader will find intimate accounts of John Frémont's obsession with mining promotion, his complicated business dealings with Judge Silent, and his attempts to recoup his family's sagging fortune. Here especially, Lily outlines a telling profile of her father, a man roundly castigated then and now as a carpetbagger less interested in promoting Arizona's interests than his own.

For students of western history, Lily Frémont's diary provides a wealth of fresh information on frontier politics, mining, army life, social customs, and ethnicity. For all readers, her words from a century ago offer new perspectives on the winning of the West as well as fascinating glimpses of a world that once was and is no more.

Armed Ambiguity is a fascinating examination of the tropes of the woman warrior constructed by print culture—including press reports, novels, dramatic works, and lyrical texts—during the decades-long conflict in Europe around 1800.

In it, Julie Koser sheds new light on how women’s bodies became a battleground for competing social, cultural, and political agendas in one of the most pivotal periods of modern history. She traces the women warriors in this work as reflections of the social and political climate in German-speaking lands, and she reveals how literary texts and cultural artifacts that highlight women’s armed insurrection perpetuated the false dichotomy of "public" versus "private" spheres along a gendered fault line. Koser illuminates how reactionary visions of "ideal femininity" competed with subversive fantasies of new femininities in the ideological battle being waged over the restructuring of German society.

Arms and the Woman: Classical Tradition and Women Writers in the Venetian Renaissance by Francesca D’Alessandro Behr focuses on the classical reception in the works of female authors active in Venice during the Early Modern Age. Even in this relatively liberal city, women had restricted access to education and were subject to deep-seated cultural prejudices, but those who read and wrote were able, in part, to overcome those limitations.

In this study, Behr explores the work of Moderata Fonte and Lucrezia Marinella and demonstrates how they used knowledge of texts by Virgil, Ovid, and Aristotle to systematically reanalyze the biased patterns apparent both in the romance epic genre and contemporary society. Whereas these classical texts were normally used to bolster the belief in female inferiority and the status quo, Fonte and Marinella used them to envision societies structured according to new, egalitarian ethics. Reflecting on the humanist representation of virtue, Fonte and Marinella insisted on the importance of peace, mercy, and education for women. These authors took up the theme of the equality of genders and participated in the Renaissance querelle des femmes, promoting women’s capabilities and nature.

Art can be a powerful avenue of resistance to oppressive governments. During the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile, some of the country’s least powerful citizens—impoverished women living in Santiago’s shantytowns—spotlighted the government’s failings and use of violence by creating and selling arpilleras, appliquéd pictures in cloth that portrayed the unemployment, poverty, and repression that they endured, their work to make ends meet, and their varied forms of protest. Smuggled out of Chile by human rights organizations, the arpilleras raised international awareness of the Pinochet regime’s abuses while providing income for the arpillera makers and creating a network of solidarity between the people of Chile and sympathizers throughout the world.

Using the Chilean arpilleras as a case study, this book explores how dissident art can be produced under dictatorship, when freedom of expression is absent and repression rife, and the consequences of its production for the resistance and for the artists. Taking a sociological approach based on interviews, participant observation, archival research, and analysis of a visual database, Jacqueline Adams examines the emergence of the arpilleras and then traces their journey from the workshops and homes in which they were made, to the human rights organizations that exported them, and on to sellers and buyers abroad, as well as in Chile. She then presents the perspectives of the arpillera makers and human rights organization staff, who discuss how the arpilleras strengthened the resistance and empowered the women who made them.

In Art for the Ladylike, Whitney Otto limns the lives of eight pioneering women photographers—Sally Mann, Imogen Cunningham, Judy Dater, Ruth Orkin, Tina Modotti, Lee Miller, Madame Yvonne, and Grete Stern—to in turn excavate her own writer’s life. The result is an affecting exploration of what it means to be a woman, what it means to be an artist, and the perils and rewards of being both at once. In considering how feminism, career, and motherhood were entangled throughout her subjects’ lives as they tirelessly sought to render their visions and paved the way for others creating within the bounds of domesticity, Otto assesses her own struggles with balancing writing and the pulls of home life. Ultimately, she ponders the persistent question that artistic women face in a world that devalues women’s ambition: If what we love is what we are, how do those of us with multiple loves forge lives with room for everything?

In her funny, idiosyncratic, and propulsive new novel, Art Is Everything, Yxta Maya Murray offers us a portrait of a Chicana artist as a woman on the margins. L.A. native Amanda Ruiz is a successful performance artist who is madly in love with her girlfriend, a wealthy and pragmatic actuary named Xōchitl. Everything seems under control: Amanda’s grumpy father is living peacefully in Koreatown; Amanda is about to enjoy a residency at the Guggenheim Museum in New York and, once she gets her NEA, she’s going to film a groundbreaking autocritical documentary in Mexico.

But then everything starts to fall apart when Xōchitl’s biological clock begins beeping, Amanda’s father dies, and she endures a sexual assault. What happens to an artist when her emotional support vanishes along with her feelings of safety and her finances? Written as a series of web posts, Instagram essays, Snapchat freakouts, rejected Yelp reviews, Facebook screeds, and SmugMug streams-of-consciousness that merge volcanic confession with eagle-eyed art criticism, Art Is Everything shows us the painful but joyous development of a mid-career artist whose world implodes just as she has a breakthrough.

In 1671, Marie Baudoin (1625–1700), head midwife and governor of the Hôtel-Dieu of Clermont-Ferrand, sent a treatise on the art of childbirth to her powerful Parisian patron, Dr. Vallant. The story of how Baudoin’s knowledge and expertise as a midwife came to be expressed, recorded, and archived raises the question: Was Baudoin exceptional because she was herself extraordinary, or because her voice has reached us through Vallant’s careful archival practices? Either way, Baudoin’s treatise invites us to reconsider the limits of what we thought we knew midwives “could be and do” in seventeenth-century France. Grounding Marie Baudoin’s text in a microanalysis of her life, work, and the Jansenist network between Paris and Clermont-Ferrand, this book connects historiographies of midwifery, Jansenism, hospital administration, public health, knowledge and record-keeping, and women’s work, underscoring both Baudoin’s capabilities and the archival accidents and intentions behind the preservation of her treatise in a letter.

In this collection of essays, ten experts in turn-of-the-century popular and material culture examine how the struggle between modernity and tradition was reflected in various facets of the household aesthetic. Their findings touch on sub-themes of gender, generation, and class to provide a fascinating commentary on what middle-class Americans were prepared to discard in the name of modernity and what they stubbornly retained for the sake of ideology. Through an examination of material culture and prescriptive literature from this period, the essayists also demonstrate how changes in artistic expression affected the psychological, social, and cultural lives of everyday Americans.

This book joins a growing list of titles dedicated to analyzing and interpreting the cultural dimensions of past domestic life. Its essays shed new light on house history by tracking the transformation of a significant element of home life - its expressions of art.

“The world is full of continuous conversations: Now is surrounded by Past, and both are encircled by Forever.” So states an unnamed narrator in As if a Bird Flew by Me.

Celia lives in the contemporary Midwest. Ann is an accused witch, executed during the Salem witch trials. Two women separated by time and place yet yoked by heritage and history. Set in three time periods, stories within stories unfold, and Greenslit’s language seamlessly weaves Celia’s modern life with the historical record of Ann’s demise alongside dazzling renderings of animal life. Greenslit’s hybrid of fiction and nonfiction occupies that rarest of airs: it is a book that illuminates, line by line and page by page, how it should be read.

Who has a right to tell us how to experience our grief? How to perform—or not perform—the roles society prescribes to us based on our various points of identity?

As If She Had a Say, the second story collection from Jennifer Fliss, uses an absurdist lens to showcase characters—predominantly women—plumbing their resources as they navigate misogyny, abuse, and grief. In these stories, a woman melts in the face of her husband’s cruelty; a seven-tablespoons-long woman lives inside a refrigerator and engages in an affair with the man of the house; a balloon-animal artist attends a funeral to discover he was invited as more than entertainment; and a man loses all his nouns.

Fans of Karen Russell and Carmen Maria Machado will appreciate how As If She Had a Say’s inventive narratives expose inequities by taking us on imaginative romps through domesticity and patriarchal expectations. Each story functions as a magnifying glass through which we might examine our own lives and see ourselves more clearly.

Stopping just before second-wave feminism brought an explosion in women's childhood autobiographical writing, As Told by Herself explores the genre's roots and development from the mid-nineteenth century, and recovers many works that have been neglected or forgotten. The result illustrates how previous generations of women—in a variety of places and circumstances—understood themselves and their upbringing, and how they thought to present themselves to contemporary and future readers.

The great Arab singer Asmahan was the toast of Cairo song and cinema in the late 1930s and early 1940s, as World War II approached. She remained a figure of glamour and intrigue throughout her life and lives on today in legend as one of the shaping forces in the development of Egyptian popular culture. In this biography, author Sherifa Zuhur does a thorough study of the music and film of Asmahan and her historical setting.

A Druze princess actually named Amal al-Atrash, Asmahan came from an important clan in the mountains of Syria but broke free from her traditional family background, left her husband, and became a public performer, a role frowned upon for women of the time.

This unique biography of the controversial Asmahan focuses on her public as well as her private life. She was a much sought-after guest in the homes of Egypt's rich and famous, but she was also rumored to be an agent for the Allied forces during World War II.

Through the story of Asmahan, the reader glimpses not only aspects of the cultural and political history of Egypt and Syria between the two world wars, but also the change in attitude in the Arab world toward women as public performers on stage. Life in wartime Cairo comes alive in this illustrated account of one of the great singers of the Arab world, a woman who played an important role in history.

This illustrated collection of annotated newspaper articles and memorials by Dorothea Dix provides a forum for the great mid-nineteenth-century humanitarian and reformer to speak for herself.

Dorothea Lynde Dix (1802–87) was perhaps the most famous and admired woman in America for much of the nineteenth century. Beginning in the early 1840s, she launched a personal crusade to persuade the various states to provide humane care and effective treatment for the mentally ill by funding specialized hospitals for that purpose. The appalling conditions endured by most mentally ill inmates in prisons, jails, and poorhouses led her to take an active interest also in prison reform and in efforts to ameliorate poverty.

In 1846–47 Dix brought her crusade to Illinois. She presented two lengthy memorials to the legislature, the first describing conditions at the state penitentiary at Alton and the second discussing the sufferings of the insane and urging the establishment of a state hospital for their care. She also wrote a series of newspaper articles detailing conditions in the jails and poorhouses of many Illinois communities.

These long-forgotten documents, which appear in unabridged form in this book, contain a wealth of information on the living conditions of some of the most unfortunate inhabitants of Illinois. In his preface, David L. Lightner describes some of the vivid images that emerge from Dorothea Dix's descriptions of social conditions in Illinois a century and a half ago: "A helpless maniac confined throughout the bitter cold of winter to a dark and filthy pit. Prison inmates chained in hallways and cellars because no more men can be squeezed into the dank and airless cells. Aged paupers auctioned off by county officers to whoever will maintain them at the lowest cost."

Lightner provides an introduction to every document, placing each memorial and newspaper article in its proper social and historical context. He also furnishes detailed notes, making these documents readily accessible to readers a century and a half later. In his final chapter, Lightner assesses both the immediate and the continuing impact of Dix's work.

The novel centers on Therese Lafirme, a widow who owns and runs a plantation in post–Civil War Louisiana. She encounters David Hosmer, who buys timber rights to her property to secure raw materials for his newly constructed sawmill. When David remarries, a love triangle develops between David, Fanny (his alcoholic wife), and Therese, who tries to balance her strong moral sensibility against her growing love for David. In depicting these relationships, Chopin acutely dramatizes the conflict between growing industrialism and the agrarian traditions of the Old South—as well as the changes to the land and the society that inevitably resulted from that conflict.

Editors Suzanne Disheroon Green and David J. Caudle provide meticulous annotations to the text of At Fault, facilitating the reader’s understanding of the complex and exotic culture and language of nineteenth-century Louisiana. Also included is a substantial body of supporting materials thatcontextualize the novel, ranging from a summary of critical responses to materials illuminating the economic, social, historical, and religious influences on Chopin’s texts.

The Editors: Suzanne Disheroon Green is an assistant professor of English at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana. She is the co-author, with David J. Caudle, of Kate Chopin: An Annotated Bibliography of Critical Works, and co-editor with Lisa Abney, of the forthcoming Songs of the New South: Writing Contemporary Louisiana

David J. Caudle, who is completing his doctorate at the University of North Texas, has published essays and book chapters dealing with American literature and linguistic approaches to literature.

In 2013, the New York Times identified Nashville as America’s “it” city—a leading hub of music, culture, technology, food, and business. But long before, the Tennessee capital was known as the “Athens of the South,” as a reflection of the city’s reputation for and investment in its institutions of higher education, which especially blossomed after the end of the Civil War and through the New South Era from 1865 to 1930.

This wide-ranging book chronicles the founding and growth of Nashville’s institutions of higher education and their impressive impact on the city, region, and nation at large. Local colleges and universities also heavily influenced Nashville’s brand of modernity as evidenced by the construction of a Parthenon replica, the centerpiece of the 1897 Centennial Exposition. By the turn of the twentieth century, Vanderbilt University had become one of the country’s premier private schools, while nearby Peabody College was a leading teacher-training institution. Nashville also became known as a center for the education of African Americans. Fisk University joined the ranks of the nation’s most prestigious black liberal-arts universities, while Meharry Medical College emerged as one of the country’s few training centers for African American medical professionals. Following the agricultural-industrial model, Tennessee A&I became the state’s first black public college. Meanwhile, various other schools— Ward-Belmont, a junior college for women; David Lipscomb College, the instructional arm of the Church of Christ; and Roger Williams University, which trained black men and women as teachers and preachers—made important contributions to the higher educational landscape. In sum, Nashville was distinguished not only by the quantity of its schools but by their quality.

Linking these institutions to the progressive and educational reforms of the era, Mary Ellen Pethel also explores their impact in shaping Nashville’s expansion, on changing gender roles, and on leisure activity in the city, which included the rise and popularity of collegiate sports. In her conclusion, she shows that Nashville’s present-day reputation as a dynamic place to live, learn, and work is due in no small part to the role that higher education continues to play in the city’s growth and development.

In 2013, the New York Times identified Nashville as America’s “it” city—a leading hub of music, culture, technology, food, and business. But long before, the Tennessee capital was known as the “Athens of the South,” as a reflection of the city’s reputation for and investment in its institutions of higher education, which especially blossomed after the end of the Civil War and through the New South Era from 1865 to 1930.