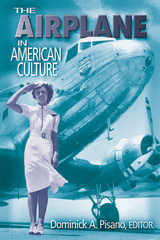

Although countless books for aviation buffs have appeared since World War II, none has attempted to place the airplane in its full social, cultural, and interdisciplinary context until now. The first book of its kind, The Airplane in American Culture presents essays by distinguished contributors including historians, literary scholars, scholars of American studies, art historians, and museum professionals that explore a range of topics, including the connections between flying and race and gender; aviation's role in forming perceptions of the landscape; the airplane's significance to the culture of war; and the influence of flight on literature and art.

A must-read collection for anyone fascinated by the airplane, The Airplane in American Culture represents a dramatic new approach to writing the history of aviation, and makes an important contribution to American social and cultural history.

Dominick A. Pisano is Curator of the Aeronautics Department at the National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution.

Elizabeth Stoddard was a gifted writer of fiction, poetry, and journalism; successfully published within her own lifetime; esteemed by such writers as William Dean Howells and Nathaniel Hawthorne; and situated at the epicenter of New York’s literary world. Nonetheless, she has been almost excluded from literary memory and importance. This book seeks to understand why. By reconsidering Stoddard’s life and work and her current marginal status in the evolving canon of American literary studies, it raises important questions about women’s writing in the 19th century and canon formation in the 20th century.

Essays in this study locate Stoddard in the context of her contemporaries, such as Dickinson and Hawthorne, while others situate her work in the context of major 19th-century cultural forces and issues, among them the Civil War and Reconstruction, race and ethnicity, anorexia and female invalidism, nationalism and localism, and incest. One essay examines the development of Stoddard’s work in the light of her biography, and others probe her stylistic and philosophic originality, the journalistic roots of her voice, and the elliptical themes of her short fiction. Stoddard’s lifelong project to articulate the nature and dynamics of woman’s subjectivity, her challenging treatment of female appetite and will, and her depiction of the complex and often ambivalent relationships that white middle-class women had to their domestic spaces are also thoughtfully considered.

The editors argue that the neglect of Elizabeth Stoddard’s contribution to American literature is a compelling example of the contingency of critical values and the instability of literary history. This study asks the question, “Will Stoddard endure?” Will she continue to drift into oblivion or will a new generation of readers and critics secure her tenuous legacy?

To lend weight to his charge that the public school teacher has been betrayed and gravity to his indictment of the educational establishment for that betrayal, Jurgen Herbst goes back to the beginnings of teacher education in America in the 1830s and traces its evolution up to the 1920s, by which time the essential damage had been done.

Initially, attempts were made to upgrade public school teaching to a genuine profession, but that ideal was gradually abandoned. In its stead, with the advent of newly emerging graduate schools of education in the early decades of the twentieth century, came the so-called professionalization of public education. At the expense of the training of elementary school teachers (mostly women), teacher educators shifted their attention to the turning out of educational "specialists" (mostly men)—administrators, faculty members at normal schools and teachers colleges, adult education teachers, and educational researchers.

Ultimately a history of the neglect of the American public school teacher, And Sadly Teach ends with a plea and a message that ring loud and clear. The plea: that the current reform proposals for American teacher education—the Carnegie and the Holmes reports—be heeded. The message: that the key to successful school reform lies in educating teacher’s true professionals and in acknowledging them as such in their classrooms.

At War offers short, accessible essays addressing the central issues in the new military history—ranging from diplomacy and the history of imperialism to the environmental issues that war raises and the ways that war shapes and is shaped by discourses of identity, to questions of who serves in the U.S. military and why and how U.S. wars have been represented in the media and in popular culture.

Robinson identifies a tradition of masculine protest and rebellion against feminization in iconic texts such as The Catcher in the Rye and Fight Club, as well as in critiques of postmodernism, academic denunciations of shopping, and a variety of other discourses that aim to diagnose what ails American consumer culture. This fresh and timely argument enters into conversation with a wide range of existing scholarship and opens up new questions for scholarly and political discussion.

More than fifty books debunking the religious claims of The Da Vinci Code have been published. Thisis the first book devoted to the fundamentally more interesting question: if those claims are so unfounded and erroneous, why have they resonated so strongly with millions of intelligent readers and filmgoers?

From the sexual abuse scandal that shook the foundations of the Catholic Church to the 9/11 terrorist attacks that cast a cloud over a troubled nation, Eric Plumer’s The Catholic Church and American Culture: Why the Claims of the DaVinci Code Struck a Chord investigates the contemporary events, ideas, and movements that fostered Dan Brown’s unprecedented dominance of best-seller lists and dinner-table conversation. This ambitious book considers the feminist movement, radical individualism, twelve-step programs, the authority of science and psychology, and other cultural developments that paved the way for The Da Vinci Code craze. It also reflects on the recent publication of the Gnostic Gospels, including the Gospel of Mary Magdalene. Plumer’s engaging book is sure to stimulate further discussion about the role of religion in contemporary life.

Conjoined twins Chang and Eng Bunker have fascinated the world since the nineteenth century. In her captivating book, Chang and Eng Reconnected, Cynthia Wu traces the “Original Siamese Twins” through the terrain of American culture, showing how their inseparability underscored tensions between individuality and collectivity in the American popular imagination.

Using letters, medical documents and exhibits, literature, art, film, and family lore, Wu provides a trans-historical analysis that presents the Bunkers as both a material presence and as metaphor. She also shows how the twins figure in representations of race, disability, and science in fictional narratives about nation building.

As astute entrepreneurs, the twins managed their own lives; nonetheless, as Chang and Eng Reconnected shows, American culture has always viewed them through the multiple lenses of difference.

With chronological chapters featuring emblematic Arctic explorers—including Elisha Kent Kane, Charles Hall, and Robert Peary—The Coldest Crucible reveals why the North Pole, a region so geographically removed from Americans, became an iconic destination for discovery.

The Cold War era spawned a host of anxieties in American society, and in response, Americans sought cultural institutions that reinforced their sense of national identity and held at bay their nagging insecurities. They saw football as a broad, though varied, embodiment of national values. College teams in particular were thought to exemplify the essence of America: strong men committed to hard work, teamwork, and overcoming pain. Toughness and defiance were primary virtues, and many found in the game an idealized American identity.

In this book, Kurt Kemper charts the steadily increasing investment of American national ideals in the presentation and interpretation of college football, beginning with a survey of the college game during World War II. From the Army-Navy game immediately before Pearl Harbor, through the gradual expansion of bowl games and television coverage, to the public debates over racially integrated teams, college football became ever more a playing field for competing national ideals. Americans utilized football as a cultural mechanism to magnify American distinctiveness in the face of Soviet gains, and they positioned the game as a cultural force that embodied toughness, discipline, self-deprivation, and other values deemed crucial to confront the Soviet challenge.

Americans applied the game in broad strokes to define an American way of life. They debated and interpreted issues such as segregation, free speech, and the role of the academy in the Cold War. College Football and American Culture in the Cold War Era offers a bold new contribution to our understanding of Americans' assumptions and uncertainties regarding the Cold War.

The popular study of conspiracy theories and why we should pay attention—completely updated for the post-9/11 world

JFK, Karl Marx, the Pope, Aristotle Onassis, Howard Hughes, Fox Mulder, Bill Clinton, both George Bushes—all have been linked to vastly complicated global (or even galactic) intrigues. Two years after Mark Fenster first published Conspiracy Theories, the attacks of 9/11 stirred the imaginations of a new generation of believers. Before the black box from United 93 had even been found, there were theories put forth from the implausible to the offensive and outrageous.

In this new edition of the landmark work, and the first in-depth look at the conspiracy communities that formed to debunk the 9/11 Commission Report, Fenster shows that conspiracy theories play an important role in U.S. democracy. Examining how and why they circulate through mass culture, he contends, helps us better understand society as a whole. Ranging from The Da Vinci Code to the intellectual history of Richard Hofstadter, he argues that dismissing conspiracy theories as pathological or marginal flattens contemporary politics and culture because they are—contrary to popular portrayal—an intense articulation of populism and, at their essence, are strident calls for a better, more transparent government. Fenster has demonstrated once again that the people who claim someone’s after us are, at least, worth hearing.

A trenchant examination of epic shifts in American thought by a major scholar in the field.

In the 1940s, American thought experienced a cataclysmic paradigm shift. Before then, national ideology was shaped by American exceptionalism and bourgeois nationalism: elites saw themselves as the children of a homogeneous nation standing outside the history and culture of the Old World. This view repressed the cultures of those who did not fit the elite vision: people of color, Catholics, Jews, and immigrants. David W. Noble, a preeminent figure in American studies, inherited this ideology. However, like many who entered the field in the 1940s, he rejected the ideals of his intellectual predecessors and sought a new, multicultural, postnational scholarship. Throughout his career, Noble has examined this rupture in American intellectual life. In Death of a Nation, he presents the culmination of decades of thought in a sweeping treatise on the shaping of contemporary American studies and an eloquent summation of his distinguished career.

Exploring the roots of American exceptionalism, Noble demonstrates that it was a doomed ideology. Capitalists who believed in a bounded nationalism also depended on a boundless, international marketplace. This contradiction was inherently unstable, and the belief in a unified national landscape exploded in World War II. The rupture provided an opening for alternative narratives as class, ethnicity, race, and region were reclaimed as part of the nation’s history. Noble traces the effects of this shift among scholars and artists, and shows how even today they struggle to imagine an alternative postnational narrative and seek the meaning of local and national cultures in an increasingly transnational world. While Noble illustrates the challenges that the paradigm shift created, he also suggests solutions that will help scholars avoid romanticized and reductive approaches toward the study of American culture in the future.

In Democratic Art, Sharon Musher explores these questions and uses them as a springboard for an examination of the role art can and should play in contemporary society. Drawing on close readings of government-funded architecture, murals, plays, writing, and photographs, Democratic Art examines the New Deal’s diverse cultural initiatives and outlines five perspectives on art that were prominent at the time: art as grandeur, enrichment, weapon, experience, and subversion. Musher argues that those engaged in New Deal art were part of an explicitly cultural agenda that sought not just to create art but to democratize and Americanize it as well. By tracing a range of aesthetic visions that flourished during the 1930s, this highly original book outlines the successes, shortcomings, and lessons of the golden age of government funding for the arts.

The contributors reveal the politics, or power, of dress, especially in its function as a symbol of American ideals, and examine changes in clothing behavior that occurred as Americans faced new experiences.

With the appearance of the urban, modern, diverse "New Negro" in the Harlem Renaissance, writers and critics began a vibrant debate on the nature of African-American identity, community, and history. Martha Jane Nadell offers an illuminating new perspective on the period and the decades immediately following it in a fascinating exploration of the neglected role played by visual images of race in that debate.

After tracing the literary and visual images of nineteenth-century "Old Negro" stereotypes, Nadell focuses on works from the 1920s through the 1940s that showcased important visual elements. Alain Locke and Wallace Thurman published magazines and anthologies that embraced modernist images. Zora Neale Hurston's Mules and Men, with illustrations by Mexican caricaturist Miguel Covarrubias, meditated on the nature of black Southern folk culture. In the "folk history" Twelve Million Black Voices, Richard Wright matched prose to Farm Security Administration photographs. And in the 1948 Langston Hughes poetry collection One Way Ticket, Jacob Lawrence produced a series of drawings engaging with Hughes's themes of lynching, race relations, and black culture. These collaborations addressed questions at the heart of the movement and in the era that followed it: Who exactly were the New Negroes? How could they attack past stereotypes? How should images convey their sense of newness, possibility, and individuality? In what directions should African-American arts and letters move?

Featuring many compelling contemporary illustrations, Enter the New Negroes restores a critical visual aspect to African-American culture as it evokes the passion of a community determined to shape its own identity and image.

With the environmental crisis comes a crisis of the imagination, a need to find new ways to understand nature and humanity's relation to it. This is the challenge Lawrence Buell takes up in The Environmental Imagination, the most ambitious study to date of how literature represents the natural environment. With Thoreau's Walden as a touchstone, Buell gives us a far-reaching account of environmental perception, the place of nature in the history of western thought, and the consequences for literary scholarship of attempting to imagine a more "ecocentric" way of being. In doing so, he provides a major new understanding of Thoreau's achievement and, at the same time, a profound rethinking of our literary and cultural reflections on nature.

The green tradition in American writing commands Buell's special attention, particularly environmental nonfiction from colonial times to the present. In works by writers from Crevecoeur to Wendell Berry, John Muir to Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson to Leslie Silko, Mary Austin to Edward Abbey, he examines enduring environmental themes such as the dream of relinquishment, the personification of the nonhuman, an attentiveness to environmental cycles, a devotion to place, and a prophetic awareness of possible ecocatastrophe. At the center of this study we find an image of Walden as a quest for greater environmental awareness, an impetus and guide for Buell as he develops a new vision of environmental writing and seeks a new way of conceiving the relation between human imagination and environmental actuality in the age of industrialization. Intricate and challenging in its arguments, yet engagingly and elegantly written, The Environmental Imagination is a major work of scholarship, one that establishes a new basis for reading American nature writing.

Pairing literary criticism and historical analysis, Berlant explores the territory of this intimate public sphere through close readings of U.S. women’s literary works and their stage and film adaptations. Her interpretation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and its literary descendants reaches from Harriet Beecher Stowe to Toni Morrison’s Beloved, touching on Shirley Temple, James Baldwin, and The Bridges of Madison County along the way. Berlant illuminates different permutations of the women’s intimate public through her readings of Edna Ferber’s Show Boat; Fannie Hurst’s Imitation of Life; Olive Higgins Prouty’s feminist melodrama Now, Voyager; Dorothy Parker’s poetry, prose, and Academy Award–winning screenplay for A Star Is Born; the Fay Weldon novel and Roseanne Barr film The Life and Loves of a She-Devil; and the queer, avant-garde film Showboat 1988–The Remake. The Female Complaint is a major contribution from a leading Americanist.

Following Tradition is an expansive examination of the history of tradition—"one of the most common as well as most contested terms in English language usage"—in Americans' thinking and discourse about culture. Tradition in use becomes problematic because of "its multiple meanings and its conceptual softness." As a term and a concept, it has been important in the development of all scholarly fields that study American culture. Folklore, history, American studies, anthropology, cultural studies, and others assign different value and meaning to tradition. It is a frequent point of reference in popular discourse concerning everything from politics to lifestyles to sports and entertainment. Politicians and social advocates appeal to it as prima facie evidence of the worth of their causes. Entertainment and other media mass produce it, or at least a facsimile of it. In a society that frequently seeks to reinvent itself, tradition as a cultural anchor to be reverenced or rejected is an essential, if elusive, concept. Simon Bronner's wide net captures the historical, rhetorical, philosophical, and psychological dimensions of tradition. As he notes, he has written a book "about an American tradition—arguing about it." His elucidation of those arguments makes fascinating and thoughtful reading. An essential text for folklorists, Following Tradition will be a valuable reference as well for historians and anthropologists; students of American studies, popular culture, and cultural studies; and anyone interested in the continuing place of tradition in American culture.

The ensuing debate over sign language invoked such fundamental questions as what distinguished Americans from non-Americans, civilized people from "savages," humans from animals, men from women, the natural from the unnatural, and the normal from the abnormal. An advocate of the return to sign language, Baynton found that although the grounds of the debate have shifted, educators still base decisions on many of the same metaphors and images that led to the misguided efforts to eradicate sign language.

"Baynton's brilliant and detailed history, Forbidden Signs, reminds us that debates over the use of dialects or languages are really the linguistic tip of a mostly submerged argument about power, social control, nationalism, who has the right to speak and who has the right to control modes of speech."—Lennard J. Davis, The Nation

"Forbidden Signs is replete with good things."—Hugh Kenner, New York Times Book Review

"The whole story is told here in this book. Carnegie's wishes, the conflicts among local groups, the architecture, development of female librarians. It's a rich and marvelous story, lovingly told."—Alicia Browne, Journal of American Culture

"This well-written and extensively researched work is a welcome addition to the history of architecture, librarianship, and philanthropy."—Joanne Passet, Journal of American History

"Van Slyck's book is a tremendous contribution for its keenness of scholarship and good writing and also for its perceptive look at a familiar but misunderstood icon of the American townscape."—Howard Wight Marshall, Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians

"[Van Slyck's] reading of the cultural coding implicit in the architectural design of the library makes a significant contribution to our understanding of the limitations of the doctrine 'free to all.'"—Virginia Quarterly Review

George Washington: Revolutionary general, Father of His Country, first president, authentic hero, prime mover in establishing a constitutional government, squire of Mount Vernon, itself a national shrine. The sheer ubiquity of his persona makes him an excellent focus for understanding how Americans from the centennial of the nation's birth to the present have rediscovered their colonial origins and have manipulated what they found for a variety of social, economic, and political purposes. The more modern we become, says Karal Ann Marling, the more desperately we cling to our Washingtons, to our old-fashioned heroes, to an imaginary lost paradise chock-full of colonial furniture.

Marling has pursued the figure of Washington from flea markets to World's Fairs in order to understand his significance in American culture and iconography. Of all American heroes, she points out, Washington is the one most closely tied to artifacts, relics, material possessions, style. She describes the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, where the federal government exhibited a scene of camp life at Valley Forge, complete with Washington's coat, pants, and other personal objects that lent a strong domestic flavor to the nascent colonial revival. When the restoration of Mount Vernon was begun in the late nineteenth century, it was financed and directed by women, as was much of the historic preservation of the period. Thanks to these efforts, the American home became the scene of successive waves of a revivalism that is still very alive in the 1980s.

In describing Washington's talismanic importance, Marling shows the efforts of twentieth-century politicians to co-opt his incorruptible image. When Harding wanted to convince Americans of his reliability and probity, he campaigned from the Colonial Revival porch of his house on Mount Vernon Avenue in Marion, Ohio. The Washington image was mined for the campaigns that celebrated Calvin Coolidge's Puritan simplicity and Herbert Hoover's engineering talents, said to be related to George Washington's career as a surveyor; more recently, Ronald Reagan at his second inaugural invoked the vision of the humble general praying in the snow at Valley Forge. The neutral and flexible Washington became whatever people wanted him to be—the decorators' darling, the doyen of the D.A.R., the model citizen held up as an example to unruly children and immigrants.

But Marling's book is about more than George Washington and the different ways in which Americans have made use of their past. In her quest for the unhistorical George, Marling has examined the subculture of American life—magazine fiction, historical romances, movies (both silent and talking), and journalism. She traces the descent of high art into such popular forms as posters, plaques, packages, and billboards, all to illuminate how Washington's iconic meaning has influenced styles and tastes on many levels.

Cheerleading has become a staple in American culture. The cheerleader straddles two contradictory symbolic poles. This individual is an instantly recognized figure representing youthful attractiveness, leadership, and popularity. Yet, for many, the cheerleader is seen as epitomizing mindless enthusiasm, shallow boosterism, and objectified sexuality. This contradictory view is explored in this extensively documented book.

Much of our most adventurous writing has occurred at history’s margins, simultaneously making use of and resisting tradition. By tracking key contemporary poets—including John Ashbery, Olena Kaltyiak Davis, Louise Glück, Czeslaw Milosz, Frank O’Hara, and C. K. Williams—as well as musing on jazz and other creative enterprises, Sadoff investigates the lively poetic art of those who have grappled with late twentieth-century attitudes about history, subjectivity, contingency, flux, and modernity. In plainspoken writing, he probes the question of the poet’s capacity to illuminate and universalize truth. Along the way, we are called to consider how and why art moves and transforms human beings.

Portrayals of Quakers—from dangerous and anarchic figures in seventeenth-century theological debates to moral exemplars in twentieth-century theater and film (Grace Kelly in High Noon, for example)—reflected attempts by writers, speechmakers, and dramatists to grapple with the troubling social issues of the day. As foils to more widely held religious, political, and moral values, members of the Society of Friends became touchstones in national discussions about pacifism, abolition, gender equality, consumer culture, and modernity.

Spanning four centuries, Imaginary Friends takes readers through the shifting representations of Quaker life in a wide range of literary and visual genres, from theological debates, missionary work records, political theory, and biography to fiction, poetry, theater, and film. It illustrates the ways that, during the long history of Quakerism in the United States, these “imaginary” Friends have offered a radical model of morality, piety, and anti-modernity against which the evolving culture has measured itself.

Winner, CHOICE Outstanding Academic Book Award

Defining the "common knowledge" a "literate" person should possess has provoked intense debate ever since the publication of E. D. Hirsch's controversial book Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know. Yet the basic concept of "common knowledge," Ramona Fernandez argues, is a Eurocentric model ill-suited to a society composed of many distinct cultures and many local knowledges.

In this book, Fernandez decodes the ideological assumptions that underlie prevailing models of cultural literacy as she offers new ways of imagining and modeling mixed cultural and non-print literacies. In particular, she challenges the biases inherent in the "encyclopedias" of knowledge promulgated by E. D. Hirsch and others, by Disney World's EPCOT Center, and by the Smithsonian Institution. In contrast to these, she places the writings of Zora Neale Hurston, Maxine Hong Kingston, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Leslie Marmon Silko, whose works model a cultural literacy that weaves connections across many local knowledges and many ways of knowing.

We see efficient criminal executives demonstrating the multifarious uses of organization; dapper, big-spending gangsters highlighting the promises and perils of the emerging consumer society; and gunmen and molls guiding an uncertain public through the shifting terrain of modern gender roles. In this fascinating study, Ruth reveals how the public enemy provides a far-ranging critique of modern culture.

The role of religion in early American literature has been endlessly studied; the role of the law has been virtually ignored. Robert A. Ferguson’s book seeks to correct this imbalance.

With the Revolution, Ferguson demonstrates, the lawyer replaced the clergyman as the dominant intellectual force in the new nation. Lawyers wrote the first important plays, novels, and poems; as gentlemen of letters they controlled many of the journals and literary societies; and their education in the law led to a controlling aesthetic that shaped both the civic and the imaginative literature of the early republic. An awareness of this aesthetic enables us to see works as diverse as Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia and Irving’s burlesque History of New York as unified texts, products of the legal mind of the time.

The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the great political orations were written by lawyers, and so too were the literary works of Trumbull, Tyler, Brackenridge, Charles Brockden Brown, William Cullen Bryant, Richard Henry Dana, Jr., and a dozen other important writers. To recover the original meaning and context of these writings is to gain new understanding of a whole era of American culture.

The nexus of law and letters persisted for more than a half-century. Ferguson explores a range of factors that contributed to its gradual dissolution: the yielding of neoclassicism to romanticism; the changing role of the writer; the shift in the lawyer’s stance from generalist to specialist and from ideological spokesman to tactician of compromise; the onslaught of Jacksonian democracy and the problems of a country torn by sectional strife. At the same time, he demonstrates continuities with the American Renaissance. And in Abraham Lincoln he sees a memorable late flowering of the earlier tradition.

Beyond their status as classic children’s stories, Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books play a significant role in American culture that most people cannot begin to appreciate. Millions of children have sampled the books in school; played out the roles of Laura and Mary; or visited Wilder homesites with their parents, who may be fans themselves. Yet, as Anita Clair Fellman shows, there is even more to this magical series with its clear emotional appeal: a covert political message that made many readers comfortable with the resurgence of conservatism in the Reagan years and beyond.

In Little House, Long Shadow, a leading Wilder scholar offers a fresh interpretation of the Little House books that examines how this beloved body of children’s literature found its way into many facets of our culture and consciousness—even influencing the responsiveness of Americans to particular political views. Because both Wilder and her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, opposed the New Deal programs being implemented during the period in which they wrote, their books reflect their use of family history as an argument against the state’s protection of individuals from economic uncertainty. Their writing emphasized the isolation of the Ingalls family and the family’s resilience in the face of crises and consistently equated self-sufficiency with family acceptance, security, and warmth.

Fellman argues that the popularity of these books—abetted by Lane’s overtly libertarian views—helped lay the groundwork for a negative response to big government and a positive view of political individualism, contributing to the acceptance of contemporary conservatism while perpetuating a mythic West. Beyond tracing the emergence of this influence in the relationship between Wilder and her daughter, Fellman explores the continuing presence of the books—and their message—in modern cultural institutions from classrooms to tourism, newspaper editorials to Internet message boards.

Little House, Long Shadow shows how ostensibly apolitical artifacts of popular culture can help explain shifts in political assumptions. It is a pioneering look at the dissemination of books in our culture that expands the discussion of recent political transformations—and suggests that sources other than political rhetoric have contributed to Americans’ renewed appreciation of individualist ideals.

Our nation began with the simple phrase, “We the People.” But who were and are “We”? Who were we in 1776, in 1865, or 1968, and is there any continuity in character between the we of those years and the nearly 300 million people living in the radically different America of today?

With Made in America, Claude S. Fischer draws on decades of historical, psychological, and social research to answer that question by tracking the evolution of American character and culture over three centuries. He explodes myths—such as that contemporary Americans are more mobile and less religious than their ancestors, or that they are more focused on money and consumption—and reveals instead how greater security and wealth have only reinforced the independence, egalitarianism, and commitment to community that characterized our people from the earliest years. Skillfully drawing on personal stories of representative Americans, Fischer shows that affluence and social progress have allowed more people to participate fully in cultural and political life, thus broadening the category of “American” —yet at the same time what it means to be an American has retained surprising continuity with much earlier notions of American character.

Firmly in the vein of such classics as The Lonely Crowd and Habits of the Heart—yet challenging many of their conclusions—Made in America takes readers beyond the simplicity of headlines and the actions of elites to show us the lives, aspirations, and emotions of ordinary Americans, from the settling of the colonies to the settling of the suburbs.

David Schmid provides a historical account of how serial killers became famous and how that fame has been used in popular media and the corridors of the FBI alike. Ranging from H. H. Holmes, whose killing spree during the 1893 Chicago World's Fair inspired The Devil in the White City, right up to Aileen Wuornos, the lesbian prostitute whose vicious murder of seven men would serve as the basis for the hit film Monster, Schmid unveils a new understanding of serial killers by emphasizing both the social dimensions of their crimes and their susceptibility to multiple interpretations and uses. He also explores why serial killers have become endemic in popular culture, from their depiction in The Silence of the Lambs and The X-Files to their becoming the stuff of trading cards and even Web sites where you can buy their hair and nail clippings.

Bringing his fascinating history right up to the present, Schmid ultimately argues that America needs the perversely familiar figure of the serial killer now more than ever to manage the fear posed by Osama bin Laden since September 11.

In Near Black, Dreisinger explores the oft-ignored history of what she calls "reverse racial passing" by looking at a broad spectrum of short stories, novels, films, autobiographies, and pop-culture discourse that depict whites passing for black. The protagonists of these narratives, she shows, span centuries and cross contexts, from slavery to civil rights, jazz to rock to hip-hop. Tracing their role from the 1830s to the present day, Dreisinger argues that central to the enterprise of reverse passing are ideas about proximity. Because "blackness," so to speak, is imagined as transmittable, proximity to blackness is invested with the power to turn whites black: those who are literally "near black" become metaphorically "near black."

While this concept first arose during Reconstruction in the context of white anxieties about miscegenation, it was revised by later white passers for whom proximity to blackness became an authenticating badge. As Dreisinger shows, some white-to-black passers pass via self-identification. Jazz musician Mezz Mezzrow, for example, claimed that living among blacks and playing jazz had literally darkened his skin. Others are taken for black by a given community for a period of time. This was the experience of Jewish critic Waldo Frank during his travels with Jean Toomer, as well as that of disc jockey Hoss Allen, master of R&B slang at Nashville's famed WLAC radio. For journalists John Howard Griffin and Grace Halsell, passing was a deliberate and fleeting experiment, while for Mark Twain's fictional white slave in Pudd'nhead Wilson, it is a near-permanent and accidental occurrence.

Whether understood as a function of proximity or behavior, skin color or cultural heritage, self-definition or the perception of others, what all these variants of "reverse passing" demonstrate, according to Dreisinger, is that the lines defining racial identity in American culture are not only blurred but subject to change.

"New Day in Babylon is an extremely intelligent synthesis, a densely textured evocation of one of American history's most revolutionary transformations in ethnic group consciousness."—Bob Blauner, New York Times

Winner of the Gustavus Myers Center Outstanding Book Award, 1993

For Cash, as for many celebrities, renown was the product of both hard work and luck. Often a visionary and always a tireless performer, he was subject to a whirlwind of social, economic, and cultural countercurrents. Nine Choices explores the tension between Cash's desire for mainstream success, his personal struggles with alcohol and drugs, and an ever-changing cultural landscape that often circumscribed his options.

Drawing on interviews, archival research, and textual analysis, Jonathan Silverman focuses on Cash's personal and artistic choices as a way of understanding his life, his impact on American culture, and the ways in which that culture in turn shaped him. Cash made decisions about where he would live, what he would play, who would produce his albums, whether he would support the Vietnam War, and even if he would flip his famous "bird"—the iconic image of Cash giving the finger which is now plastered on posters and T-shirts everywhere—in the context of cultural forces both visible and opaque. He made other decisions in consultation with a variety of people, many of whom were chiefly concerned with the reaction of his audiences.

Less a conventional biography than a study of the making of an identity, Nine Choices explores how Johnny Cash sought to define who he was, how he was perceived, and what he signified through a series of self-conscious actions. The result, Silverman shows, was a life that was often tumultuous but never uninteresting.

How it got to be that way and how it changed the face of American popular culture are the subjects of this concise study of Berry Gordy's phenomenal creation. Author Gerald Early tells the story of the cultural and historical conditions that made Motown Records possible, including the dramatic shifts in American popular music of the time, changes in race relations and racial attitudes, and the rise of a black urban population. Early concentrates in particular on the 1960s and 70s, when Motown had its biggest impact on American musical tastes and styles.

With this revised and expanded edition, the author provides an up-to-date bibliography of the major books that have been written about Motown Records specifically, and black American music generally. Plus, new appendices feature interviews with four of the major creators of the Motown Sound: Berry Gordy, Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross, and Marvin Gaye.

Although Americans claim to revere the Constitution, relatively few understand its workings. Its real importance for the average citizen is as an enduring reminder of the moral vision that shaped the nation's founding. Yet scholars have paid little attention to the broader appeal that constitutional idealism has always made to the American imagination through publications and films. Maxwell Bloomfield draws upon such neglected sources to illustrate the way in which media coverage contributes to major constitutional change.

Successive generations have sought to reaffirm a sense of national identity and purpose by appealing to constitutional norms, defined on an official level by law and government. Public support, however, may depend more on messages delivered by the popular media. Muckraking novels, such as Upton Sinclair's The Jungle (1906), debated federal economic regulation. Woman suffrage organizations produced films to counteract the harmful gender stereotypes of early comedies. Arguments over the enforcement of black civil rights in the Civil Rights Cases and Plessy v. Ferguson took on new meaning when dramatized in popular novels.

From the founding to the present, Americans have been taught that even radical changes may be achieved through orderly constitutional procedures. How both elite and marginalized groups in American society reaffirmed and communicated this faith in the first three decades of the twentieth century is the central theme of this book.

At about the same time that the 1896 Supreme Court Plessy v. Ferguson decision hardened the racialized boundary between black and white, prominent trials were drawing the public’s attention to emerging categories of sexual identity. Somerville argues that these concurrent developments were not merely parallel but in fact inextricably interrelated and that the discourses of racial and sexual “deviance” were used to reinforce each other’s terms. She provides original readings of such texts as Havelock Ellis’s late nineteenth-century work on “sexual inversion,” the 1914 film A Florida Enchantment, the novels of Pauline E. Hopkins, James Weldon Johnson’s Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man, and Jean Toomer’s fiction and autobiographical writings, including Cane. Through her analyses of these texts and her archival research, Somerville contributes to the growing body of scholarship that focuses on discovering the intersections of gender, race, and sexuality.

Queering the Color Line will have broad appeal across disciplines including African American studies, gay and lesbian studies, literary criticism, cultural studies, cinema studies, and gender studies.

Edith Blumhofer uses the Assemblies of God, the largest classical Pentecostal denomination in the world, as a lens through which to view the changing nature of Anglo Pentecostalism in the United States. She illustrates how the original mission to proclaim the end resulted in the development of Bible schools, the rise of the charismatic movement, and the popularity of such figures as Aimee Semple McPherson, Charles Fox Parham, and David Du Plessis. Blumhofer also examines the sect's use of radio and television and the creation of a parallel Christian culture

In this book Eoin Cannon illuminates the role that sobriety movements have played in placing notions of personal and societal redemption at the heart of modern American culture. He argues against the dominant scholarly perception that recovery narratives are private and apolitical, showing that in fact the genre's conventions turn private experience to public political purpose. His analysis ranges from neglected social reformer Helen Stuart Campbell's embrace of the "gospel rescue missions" of postbellum New York City to William James's use of recovery stories to consider the regenerative capabilities of the mind, to writers such as Upton Sinclair and Djuna Barnes, who used this narrative form in much different ways.

Cannon argues that rather than isolating recovery from these realms of wider application, the New Deal–era Alcoholics Anonymous refitted the "drunkard's conversion" as a model of selfhood for the liberal era, allowing for a spiritual redemption story that could accommodate a variety of identities and compulsions. He concludes by considering how contemporary recovery narratives represent both a crisis in liberal democracy and a potential for redemptive social progress.

Science news is met by the public with a mixture of fascination and disengagement. On the one hand, Americans are inflamed by topics ranging from the question of whether or not Pluto is a planet to the ethics of stem-cell research. But the complexity of scientific research can also be confusing and overwhelming, causing many to divert their attentions elsewhere and leave science to the “experts.”

Whether they follow science news closely or not, Americans take for granted that discoveries in the sciences are occurring constantly. Few, however, stop to consider how these advances—and the debates they sometimes lead to—contribute to the changing definition of the term “science” itself. Going beyond the issue-centered debates, Daniel Patrick Thurs examines what these controversies say about how we understand science now and in the future. Drawing on his analysis of magazines, newspapers, journals and other forms of public discourse, Thurs describes how science—originally used as a synonym for general knowledge—became a term to distinguish particular subjects as elite forms of study accessible only to the highly educated.

While focusing on the changing practice of contact improvisation through two decades of social transformation, Novack’s work incorporates the history of rock dancing and disco, the modern and experimental dance movements of Merce Cunningham, Anna Halprin, and Judson Church, among others, and a variety of other physical activities, such as martial arts, aerobics, and wrestling.

Tracing the western from its hazy silent-picture origins in the 1890s to the advent of talking pictures in the 1920s, Smith examines the ways in which silent westerns contributed to the overall development of the film industry.

Focusing on such early important production companies as Selig Polyscope, New York Motion Picture, and Essanay, Smith revises current thinking about the birth of Hollywood and the establishment of Los Angeles as the nexus of filmmaking in the United States. Smith also reveals the role silent westerns played in the creation of the white male screen hero that dominated American popular culture in the twentieth century.

Illustrated with dozens of historic photos and movie stills, this engaging and substantive story will appeal to scholars interested in Western history, film history, and film studies as well as general readers hoping to learn more about this little-known chapter in popular filmmaking.

The collection blends original and classic essays to reveal the interconnections among art, literature, public policy, the history of medicine, and theories about sexuality with regard to bodies that are both black and female. Contributors include Rachel Adams, Elizabeth Alexander, Lisa Collins, Bridgette Davis, Lisa E.Farrington, Anne Fausto-Sterling, Beverly Guy-Sheftall, Evelynn Hammonds, Terri Kapsalis, Jennifer L. Morgan, Siobhan B. Somerville, Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, Carla Williams, and Doris Witt.

Skin Deep, Spirit Strong: The Black Female Body in American Culture will appeal to both the academic reader attempting to integrate race into discussion about the female body and to the general reader curious about the history of black female representation.

Kimberly Wallace-Sanders is Assistant Professor, Graduate Institute of Liberal Arts and Institute of Women's Studies, Emory University.

Moon illuminates the careers of James, Warhol, and others by examining the imaginative investments of their protogay childhoods in their work in ways that enable new, more complex cultural readings. He deftly engages notions of initiation and desire not within the traditional framework of “sexual orientation” but through the disorienting effects of imitation. Whether invoking the artist Joseph Cornell’s early fascination with the Great Houdini or turning his attention to James’s self-described “initiation into style” at the age of twelve—when he first encountered the homoerotic imagery in paintings by David, Géricault, and Girodet—Moon reveals how the works of these artists emerge from an engagement that is obsessive to the point of “queerness.”

Rich in historical detail and insistent in its melding of the recent with the remote, the literary with the visual, the popular with the elite, A Small Boy and Others presents a hitherto unimagined tradition of brave and outrageous queer invention. This long-awaited contribution from Moon will be welcomed by all those engaged in literary, cultural, and queer studies.

In Soccer in American Culture: The Beautiful Game’s Struggle for Status, G. Edward White seeks to answer two questions. The first is why the sport of soccer failed to take root in the United States when it spread from England around much of the rest of the world in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The second is why the sport has had a significant renaissance in America since the last decade of the twentieth century, to the point where it is now the 4th largest participatory sport in the United States and is thriving, in both men’s and women’s versions, at the high school, college, and professional levels.

White considers the early history of “Association football” (soccer) in England, the persistent struggles by the sport to establish itself in America for much of the twentieth century, the role of public high schools and colleges in marginalizing the sport, the part played by FIFA, the international organization charged with developing soccer around the globe, in encumbering the development of the sport in the United States, and the unusual history of women’s soccer in America, which evolved in the twentieth century from a virtually nonexistent sport to a major factor in the emergence of men’s—as well as women's—soccer in the U.S. in the twentieth century.

Incorporating insights from sociology and economics, White explores the multiple factors that have resulted in the sport of soccer struggling to achieve major status in America and why it currently has nothing like the cultural impact of other popular American sports—baseball and American football— which can be seen by the comparative lack of attention paid to it in sports media, its low television ratings, and virtually nonexistent radio broadcast coverage.

The first comprehensive study of the influence British programming had on American television.

The first comprehensive study of the influence British programming had on American television.

Between Emma Peel and the Ministry of Silly Walks, British television had a significant impact on American popular culture in the 1960s and 1970s. In Something Completely Different, Jeffrey Miller offers the first comprehensive study of British programming on American television, discussing why the American networks imported such series as The Avengers and Monty Python’s Flying Circus; how American audiences received these uniquely British shows; and how the shows’ success reshaped American television.Miller’s lively analysis covers three genres: spy shows, costume dramas, and sketch comedies. In addition to providing his close readings of the series themselves, Miller considers the networks’ packaging of the programs for American viewers and the influences that led to their acceptance, including the American television industry’s search for new advertising revenue and the creation of PBS.Something Completely Different concludes with a discussion of the American programs and genres that owed their existence to British progenitors. Miller convincingly argues that much of what came to define American television by 1980 was in fact British in origin, a contention that casts a new light on traditional discussions of American cultural imperialism.ISBN 0-8166-3240-5 Cloth £31.00 $44.95xxISBN 0-8166-3241-3 Paper £12.50 $17.95x208 Pages 17 black-and-white photos 5 7/8 x 9 JanuaryTranslation inquiries: University of Minnesota Press

How does a blatant lying in TV commercials—like Joe Isuzu's manic claims—create public trust in a product or a company? How does a company associated with a disaster, Exxon or Du Pont for example, restore its reputation? What is the real story behind the rendering of the now infamous Joe Camel? And what is the deeper meaning of living in an ad, ad, ad world? For a decade, journalist Leslie Savan has been exposing the techniques used by advertisers to push products and pump up corporate images. In the lively essays in this collection, Savan penetrates beneath the slick surfaces of specific ads and marketing campaigns to show how they reflect and shape consumer desires.

Savan's interviews with ad agencies and corporate clients—along with her insightful analyses of influential TV sports—reveal how successful advertising works. Ads do more than command attention. They are signposts to the political, cultural, and social trends that infiltrate the individual consumer's psyche. Think of the products associated with corporate mascots—the drum-beating bunny, the cereal-pushing tiger, the doughboy—that have become pop culture icons. Think cool. Think of the clothing manufacturer that uses multiracial imagery. Think progressive. Buy their worldview, buy their product. When virtually every product can be associate with some positive self-image, we are subtly refashioned into the advertiser's concept of a good citizen. Like it or not, we lead "the sponsored life."

Studies in American Culture was first published in 1960. Minnesota Archive Editions uses digital technology to make long-unavailable books once again accessible, and are published unaltered from the original University of Minnesota Press editions.

The last decade has seen a revolutionary interest at colleges and universities both in this country and abroad in the field known variously as American Studies, American Civilization, or American Culture. Now the time is ripe for a critical look at the field, to assess its intellectual and cultural problems, and to anticipate its future. This is what the contributors to this volume do, through thoughtful discussions and interesting examples of studies in American ideas and images.

There are sixteen contributors, members of the faculties of a number of colleges and universities, and representatives of various specialties such as literary history and criticism; social, intellectual, and aesthetic history; political, economic, and social theory.

In the introductory chapter, Henry Nash Smith discusses the problems of method which confront scholars in American Studies. The chapters which follow contain outstanding examples of scholarship in American Studies. The authors are Reuel Denney, John W. Ward, Mulford Q. Sibley, David R. Weimer, William Van O'Connor, Bernard Bowron, Leo Marx, Arnold Rose, Allen Tate, David W. Noble, J. C. Levenson, Joseph J. Kwiat, Theodore C. Blegen, and Charles H. Foster. In the final chapter, Robert E. Spiller looks at the past, present, and future of American Studies.

All the contributors as well as the editors are now or have been associated with the American Studies program at the University of Minnesota and with the late Tremaine McDowell, chairman of the program for thirteen years and a pioneer in the development of the discipline.

The book will be useful to anyone interested in American thought, culture, and society, to those conducting American Studies programs, and to their students.

"Swingin' the Dream is an intelligent, provocative study of the big band era, chiefly during its golden hours in the 1930s; not merely does Lewis A. Erenberg give the music its full due, but he places it in a larger context and makes, for the most part, a plausible case for its importance."—Jonathan Yardley, Washington Post Book World

"An absorbing read for fans and an insightful view of the impact of an important homegrown art form."—Publishers Weekly

"[A] fascinating celebration of the decade or so in which American popular music basked in the sunlight of a seemingly endless high noon."—Tony Russell, Times Literary Supplement

Addresses the relationships between what modern-day experts say to each other and to their constituencies

Technical Knowledge in American Culture addresses the relationships between what modern-day experts say to each other and to their constituencies and whether what they say and do relates to the larger culture, society, and era. These essays challenge the social impact model by looking at science, technology, and medicine not as social activities but as intellectual activities.

The essays collected here focus on women in front of, behind, and on the TV screen, as producers, viewers, and characters. Using feminist and historical criticism, the contributors investigate how television has shaped our understanding of gender, power, race, ethnicity, and sexuality from the 1950s to the present. The topics range from the role that women broadcasters played in radio and early television to the attempts of Desilu Productions to present acceptable images of Hispanic identity, from the impact of TV talk shows on public discourse and the politics of offering viewers positive images of fat women to the negotiation of civil rights, feminism, and abortion rights on news programs and shows such as I Spy and Peyton Place.

Innovative and accessible, this book will appeal to those interested in women’s studies, American studies, and popular culture and the critical study of television.

Contributors. Julie D’Acci, Mary Desjardins, Jane Feuer, Mary Beth Haralovich, Michele Hilmes, Moya Luckett, Lauren Rabinovitz, Jane M. Shattuc, Mark Williams

The rhetoric, or discourse, of early American theater emerged out of the figures of speech that permeated the colonists’ lives and literary productions. Jeffrey H. Richards examines a variety of texts—histories, diaries, letters, journals, poems, sermons, political tracts, trial transcripts, orations, and plays—and looks at the writings of such authors as John Winthrop and Mercy Otis Warren. Richards places the American usage of theatrum mundi—the world depicted as a stage—in the context of classical and Renaissance traditions, but shows how the trope functions in American rhetoric as a register for religious, political, and historical attitudes.

The definitive account of how conservative Southern Baptists came to dominate the nation's largest Protestant denomination

In 1979 a group of conservative members of the Southern Baptists Convention (SBC) initiated a campaign to reshape the denomination’s seminaries and organizations by installing new conservative leaders who made belief in the inerrancy of the Bible a condition of service. They succeeded. This book is a definitive account of that takeover.

Barry Hankins argues that the conservatives sought control of the SBC not or not only to secure the denomination's orthodoxy but to mobilize Southern Baptists for a war against secular culture. The best explanation of the beliefs and behavior of Southern Baptist conservatives, Hankins concludes, lies in their adoption of the culture war model of American society. Believing that "American culture has turned hostile to traditional forms of faith,” they sought to deploy the Southern Baptist Convention in a "full-scale culture war" against secularism in the United States. Hankins traces the roots of this movement to the ideas of such post-WWII northern evangelicals as Carl F. H. Henry and Francis Schaeffer. Henry and Schaeffer viewed America's secular culture as hostile to Christianity and called on evangelicals to develop a robust Christian opposition to secular culture. As the nation’s largest Protestant denomination, SBC positions on divisive cultural issues like abortion have remade the American political landscape, most notably in the reversal of Roe v. Wade.

Hankins also argues, however, that Southern Baptist conservatives sought more than orthodox adherence to Biblical inerrancy. They also sought an identity that was authentically Baptist and Southern. Hankin’s excellent and prescient work will fascinate readers interested in contemporary American religion, culture, and public policy, as well as in the American South.

In Vaudeville Melodies, Nicholas Gebhardt introduces us to the performers, managers, and audiences who turned disjointed variety show acts into a phenomenally successful business. First introduced in the late nineteenth century, by 1915 vaudeville was being performed across the globe, incorporating thousands of performers from every branch of show business. Its astronomical success relied on a huge network of theatres, each part of a circuit and administered from centralized booking offices. Gebhardt shows us how vaudeville transformed relationships among performers, managers, and audiences, and argues that these changes affected popular music culture in ways we are still seeing today. Drawing on firsthand accounts, Gebhardt explores the practices by which vaudeville performers came to understand what it meant to entertain an audience, the conditions in which they worked, the institutions they relied upon, and the values they imagined were essential to their success.

A Very Serious Thing was first published in 1988. Minnesota Archive Editions uses digital technology to make long-unavailable books once again accessible, and are published unaltered from the original University of Minnesota Press editions.

"It is a very serious thing to be a funny woman." –Frances Miriam Berry Whitcher

A Very Serious Thing is the first book-length study of a part of American literature that has been consistently neglected by scholars and underrepresented in anthologies—American women's humorous writing. Nancy Walker proposes that the American humorous tradition to be redefined to include women's humor as well as men's, because, contrary to popular opinion, women do have a sense of humor.

Her book draws on history, sociology, anthropology, literature, and psychology to posit that the reasons for neglect of women's humorous expression are rooted in a male-dominated culture that has officially denied women the freedom and self-confidence essential to the humorist. Rather than a study of individual writers, the book is an exploration of relationships between cultural realities—including expectations of "true womanhood"—and women's humorous response to those realities.

Humorous expression, Walker maintains, is at odds with the culturally sanctioned ideal of the "lady," and much of women's humor seems to accept, while actually denying, this ideal. In fact, most of American women's humorous writing has been a feminist critique of American culture and its attitudes toward women, according to the author.

"Have you taken your vitamins today?" That question echoes daily through American households. Thanks to intensive research in nutrition and medicine, the importance of vitamins to health is undisputed. But millions of Americans believe that the vitamins they get in their food are not enough. Vitamin supplements have become a multibillion-dollar industry. At the same time, many scientists, consumer advocacy groups, and the federal Food and Drug Administration doubt that most people need to take vitamin pills.

Vitamania tells how and why vitamins have become so important to so many Americans. Rima Apple examines the claims and counterclaims of scientists, manufacturers, retailers, politicians, and consumers from the discovery of vitamins in the early twentieth century to the present. She reveals the complicated interests--scientific, professional, financial--that have propelled the vitamin industry and its would-be regulators. From early advertisements linking motherhood and vitamin D, to Linus Pauling's claims for vitamin C, to recent congressional debates about restricting vitamin products, Apple's insightful history shows the ambivalence of Americans toward the authority of science. She also documents how consumers have insisted on their right to make their own decisions about their health and their vitamins.

Vitamania makes fascinating reading for anyone who takes--or refuses to take--vitamins. It will be of special interest to students, scholars, and professionals in public health, the biomedical sciences, history of medicine and science, twentieth-century history, nutrition, marketing, and consumer studies.

World War II posed a crisis for American culture: to defeat the enemy, Americans had to unite across the class, racial and ethnic boundaries that had long divided them. Exploring government censorship of war photography, the revision of immigration laws, Hollywood moviemaking, swing music, and popular magazines, these essays reveal the creation of a new national identity that was pluralistic, but also controlled and sanitized. Concentrating on the home front and the impact of the war on the lives of ordinary Americans, the contributors give us a rich portrayal of family life, sexuality, cultural images, and working-class life in addition to detailed consideration of African Americans, Latinos, and women who lived through the unsettling and rapidly altered circumstances of wartime America.

The development of an American wine ethos.

The history of wine is a tale of capitalist production and consumer experience, and early Americans embraced the idea of having their own wine culture. But many began to believe that excessive alcohol consumption had become a moral, ethical, economic, political, social, and health conundrum. The result was a national on-again, off-again relationship with the concept of an American wine culture.

Citizens struggled to build a wine culture patterned after their diasporic European custom of wine as a moderating beverage that was part of a healthy diet. Yet, as America grew, untold attempts to create a wine culture failed due to climate, pests, diseases, wars, and depressions, resulting in some people considering the nation an alcoholic republic. Thus began an anti-alcohol culture war aimed at restricting or prohibiting alcoholic beverages.

With the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment (Prohibition), a culture war started between wet and dry proponents. After the repeal of Prohibition, the decimated wine industry responded by forming the Wine Institute to rebrand wine’s role in American society, after which neoprohibitionists attempted to restrict alcohol availability and consumption. To confront these aggressive actions, the Wine Institute hired politically trained John A. De Luca to navigate the new attacks and pushed for rebranding wine as a cultural spirit with health benefits.

READERS

Browse our collection.

PUBLISHERS

See BiblioVault's publisher services.

STUDENT SERVICES

Files for college accessibility offices.

UChicago Accessibility Resources

home | accessibility | search | about | contact us

BiblioVault ® 2001 - 2025

The University of Chicago Press